🕳️ Ecologies of absence: From textile to utopian city—Reinterpreting Otti Berger

Editorial note: This work has been created in the context of the Bauhaus Open Studios programme by students from the Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb (studio leads: Nikola Bojić, Ivan Skvrce, Marko Tadić) in October 2025. Engaging with selected objects from the collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb (MSU)—textile fragments by Otti Berger, Ivana Tomljenović’s experimental film, and the correspondence of Marie-Luise Betlheim and Lou Scheper—the student research group explored not only what is present and preserved, but also what is absent and lost. They ask whether fragments can become active models for learning, and whether forms such as friendships, memories, and gestures of care can guide us in thinking about ecology, responsibility, and shared futures. Collections thus are not static repositories, but learning environments—ecologies in which human and non-human, personal and collective, past and present, remain fragmented and incomplete, yet living and entangled.

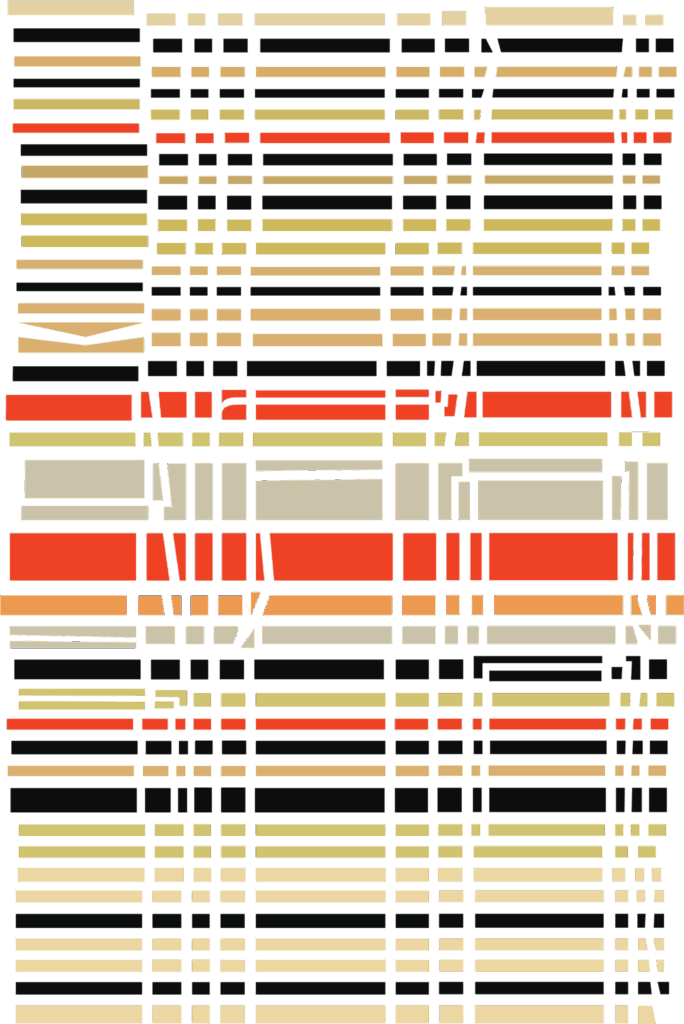

Our project takes as its starting point a textile fragment by Otti Berger, a Bauhaus student and later head of the weaving workshop, whose work embodies the intersection of craft, design, and spatial thinking. Among the many objects in the collection, this fragment immediately stood out to us, not only for its material qualities but for the strong graphic impression it made on us: a composition of lines, individual parts, and irregular curves. Its arrangement intrigued us for exploration: we began to view this textile as a plan, a network, or even as a place for a city to grow. In this sense, we sought to activate a position of the object preserved in a collection by reinterpreting it as a living framework, not a static artifact. With this in mind, research questions that guided us in the process were:

How can Otti Berger’s textile logic; its colors, structures, and material qualities, be translated across media into spatial form?

What does this act of translation reveal about the shift from intimate human scale (textile) to more collective- public space (architectural/urban model)?

How can such experiments with historical material and digital tools function as speculative models? More about imagining possibilities than producing blueprints; for learning from collections today.

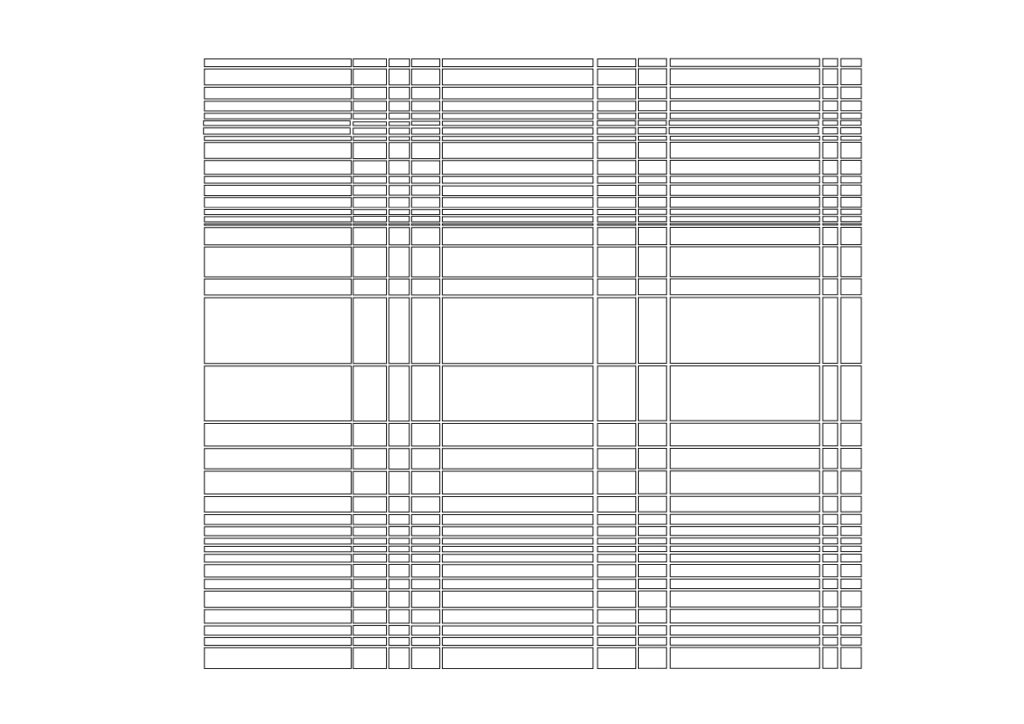

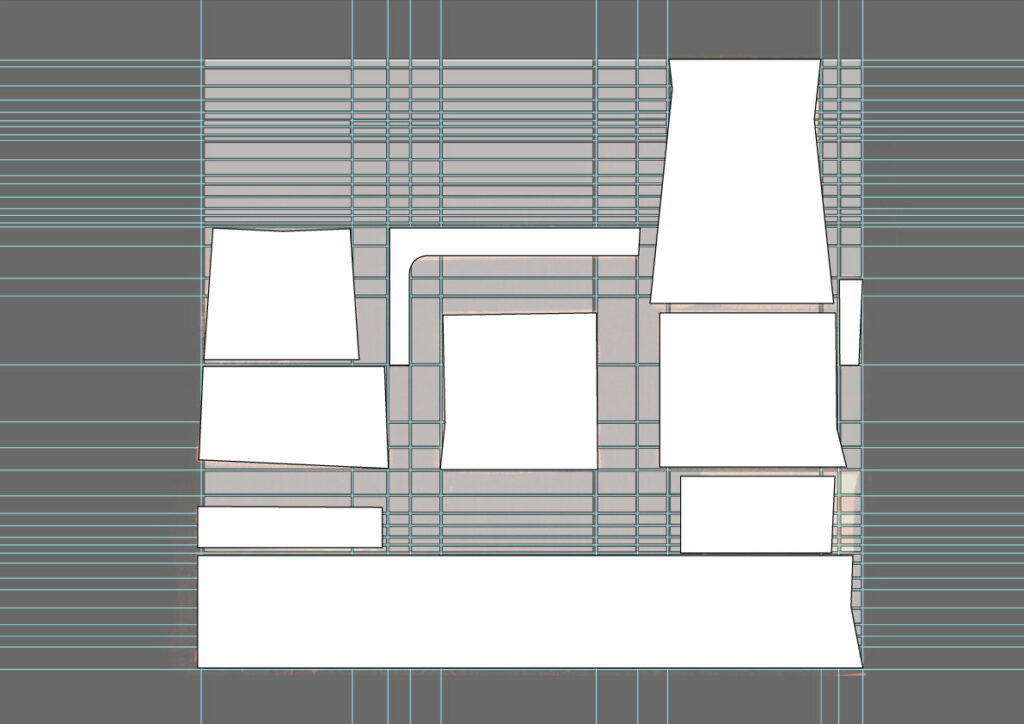

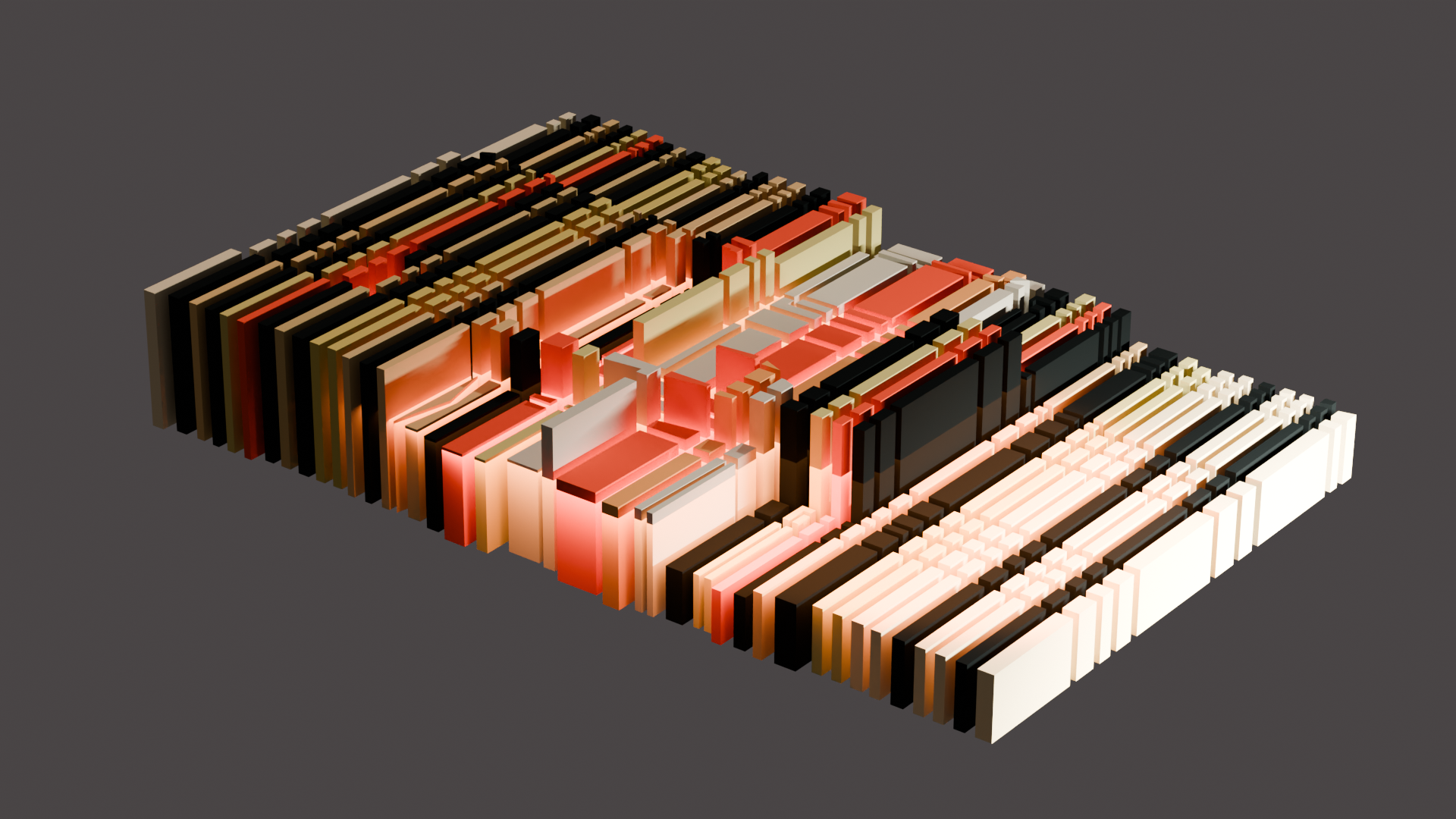

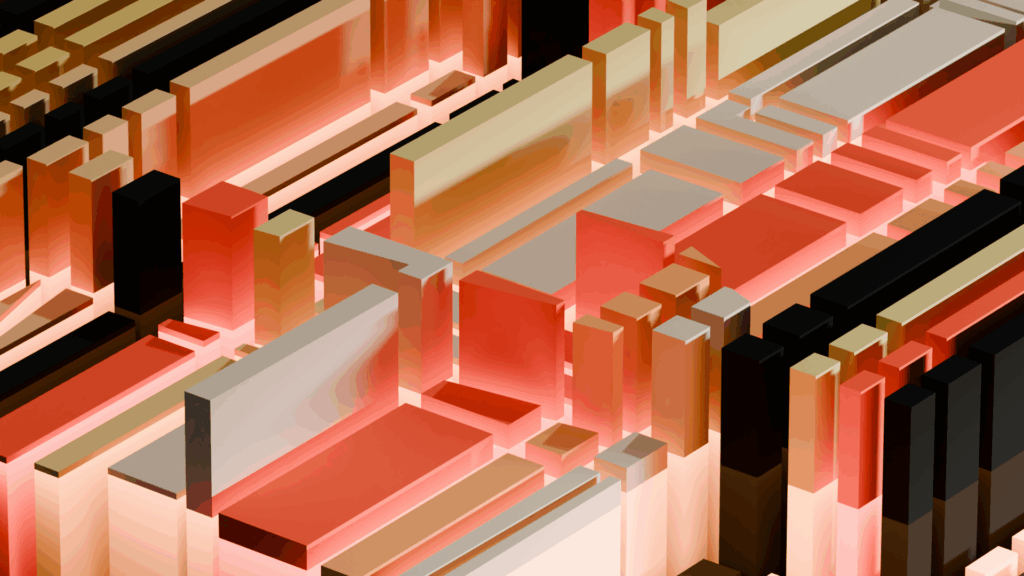

The process began with the digital tracing of the textile’s motifs. We digitized the textile through vector programs, extracting its compositional logic into a grid. This act of translation transformed something intimate and domestic into a tool for public projection; the fabric became a plan, the private object a prototype for shared space. This grid became the structural backbone of our experiments, allowing us to move in multiple directions. Vertically, we extruded modules into three-dimensional volumes, testing how patterns could be inhabited as architecture. Horizontally, we multiplied and extended the grid across multiple variants, using them to generate larger, modular configurations. In both cases, the textile became more than itself; it became a device for imagining collectivity.

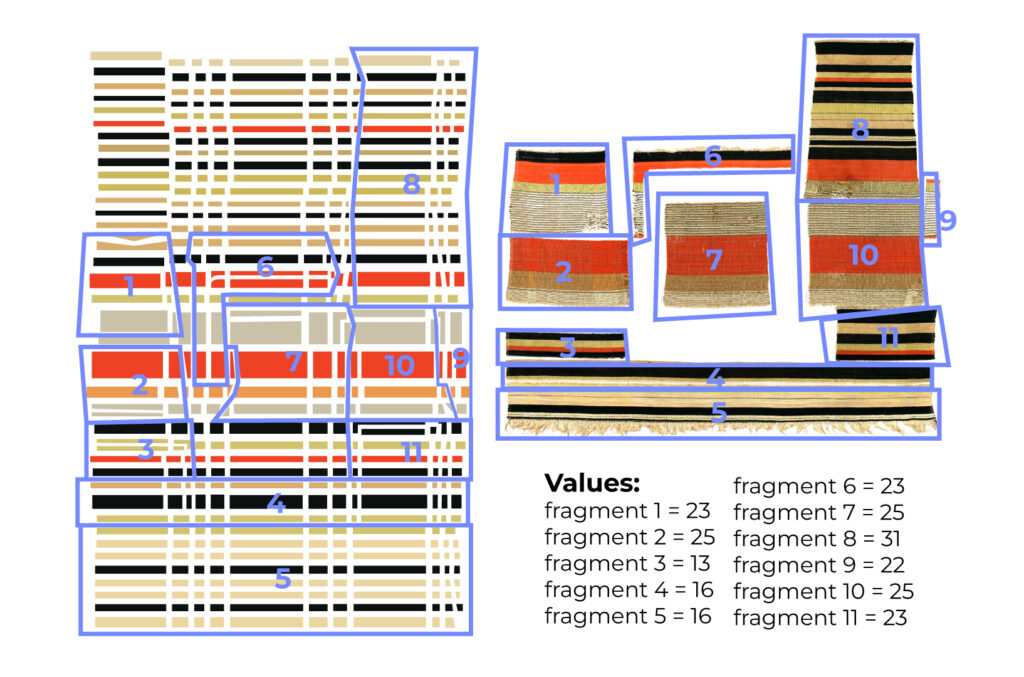

A key methodological step was assigning numerical values to the elements of the textile. To translate the textile’s qualities into spatial values, we turned to Itten’s theory of contrast. Colors were divided into warm, neutral, and cool tones and then assigned numerical values along a dark–light spectrum, with black at one and white at ten. The remaining hues occupied intermediate positions, and the values of each textile fragment were determined by summing the colors within it, giving the pieces a new dimensional logic that could be directly applied to height. Introducing this systematic method for giving form, what emerged was not a single, final object, but multiple possibilities; variations that encouraged a learning environment, where experimentation and iteration were central.

Throughout, we were drawn to the tensions in play: the softness of fabric against the rigidness of architecture; the domestic scale of weaving versus the urban scale of planning; the private act of weaving reframed as a collective, public proposition. A textile is always a network of relationships, warp and weft intersecting, supporting, holding. Recasting it as an architectural grid highlights the social dimension of space: how individuals, like threads, come together to form patterns larger than themselves.

Inspiration for further development was the concept of Mat-Buildings, which reinforced this reading. Mat-Buildings, as theorized in architectural discourse, emphasize horizontality, modularity, and adaptability, prioritizing open networks over vertical monumentality. Translated into our project, this suggested an urban fabric that is at once structured and flexible, echoing the qualities of a woven textile. By situating Berger’s fragment within this discourse, we created an active dialogue between a historical artifact and contemporary artistic research.

In parallel, we drew on theoretical ideas from Richard Noble’s Utopias about the architectural model as a medium. The appeal of the model lies not only in its capacity to represent but also to imagine: to project “other ways of being,” to explore possible worlds and “what ifs.” In this sense, our experiments with Berger’s textile do not function as blueprints for an actual urban plan, but as critical models; tools that reveal both how things might be otherwise and how far the present is from its own potential. The translation of a woven fragment into space thus embodies the tension between critique and possibility: it acknowledges the constraints of the current world while imagining a different, perhaps better one. In this way, the architectural model becomes less about building and more about envisioning a “shining city on the hill” that illuminates the present by contrast.

At its core, the project demonstrates how a fragment from a collection can be activated into a living process. Rather than aiming for a final solution, we have intended to document the transformations of a single textile fragment as it shifts across digital media and scales. For us, this project was not about producing a finished product but about learning from Berger’s logic of composition, learning through digital experimentation, and about how private objects can become a blueprint for big imaginary worlds. In this way, the project becomes both homage and extension, carrying forward Bauhaus principles of experimentation, communication, and community into our own artistic research.

Technically, our workflow reflected a hybrid approach. Illustrator was used for vector tracing, clarifying patterns, and initial 3D experiments, but the limitations of graphic software quickly led us to Blender. This enabled precise modeling, controlled extrusion, and rendering under different lighting and atmospheric conditions. These tools not only helped us visualize but also gave our project the sense of a learning environment: by challenging us to move across media, learn new tools to achieve further goals in the research, test ideas iteratively, and give new meanings to historical work.

are MA students at the Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb