🕳️ Ecologies of absence: Talk to me soon and in detail!

Editorial note: This work has been created in the context of the Bauhaus Open Studios programme by students from the Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb (studio leads: Nikola Bojić, Ivan Skvrce, Marko Tadić) in October 2025. Engaging with selected objects from the collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb (MSU)—textile fragments by Otti Berger, Ivana Tomljenović’s experimental film, and the correspondence of Marie-Luise Betlheim and Lou Scheper—the student research group explored not only what is present and preserved, but also what is absent and lost. They ask whether fragments can become active models for learning, and whether forms such as friendships, memories, and gestures of care can guide us in thinking about ecology, responsibility, and shared futures. Collections thus are not static repositories, but learning environments—ecologies in which human and non-human, personal and collective, past and present, remain fragmented and incomplete, yet living and entangled.

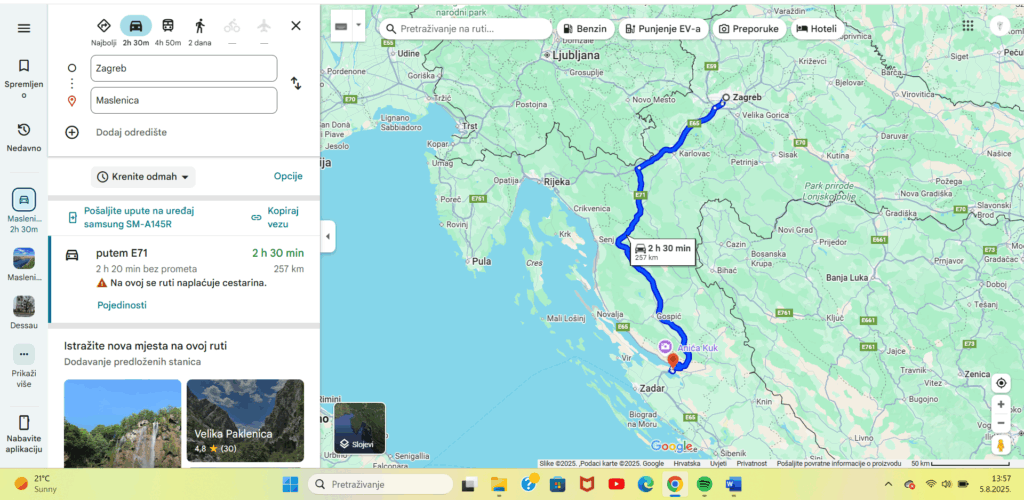

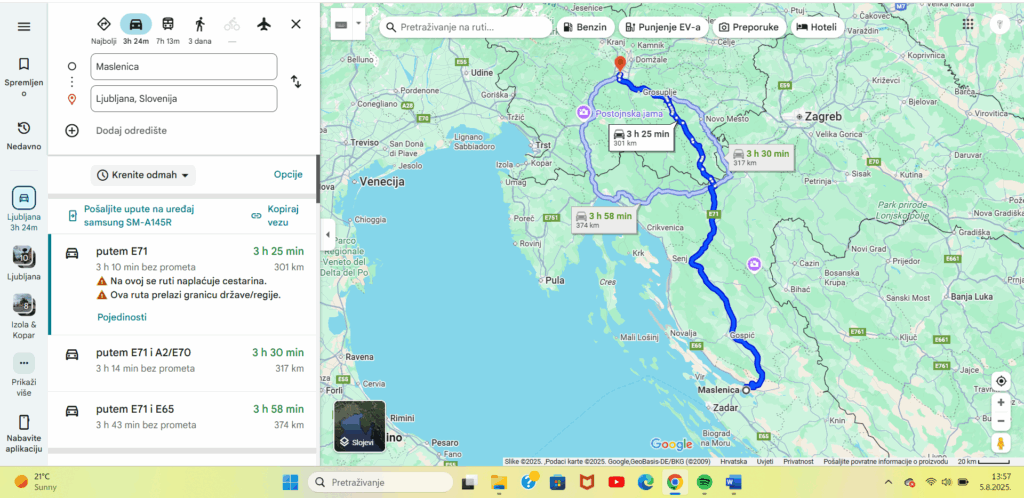

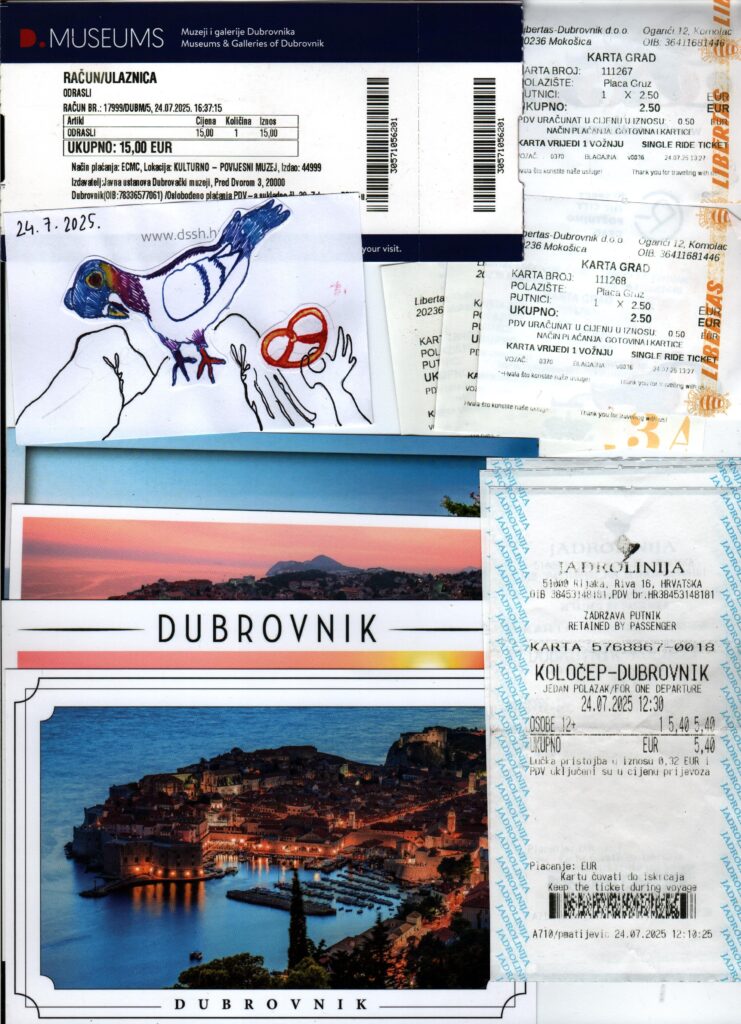

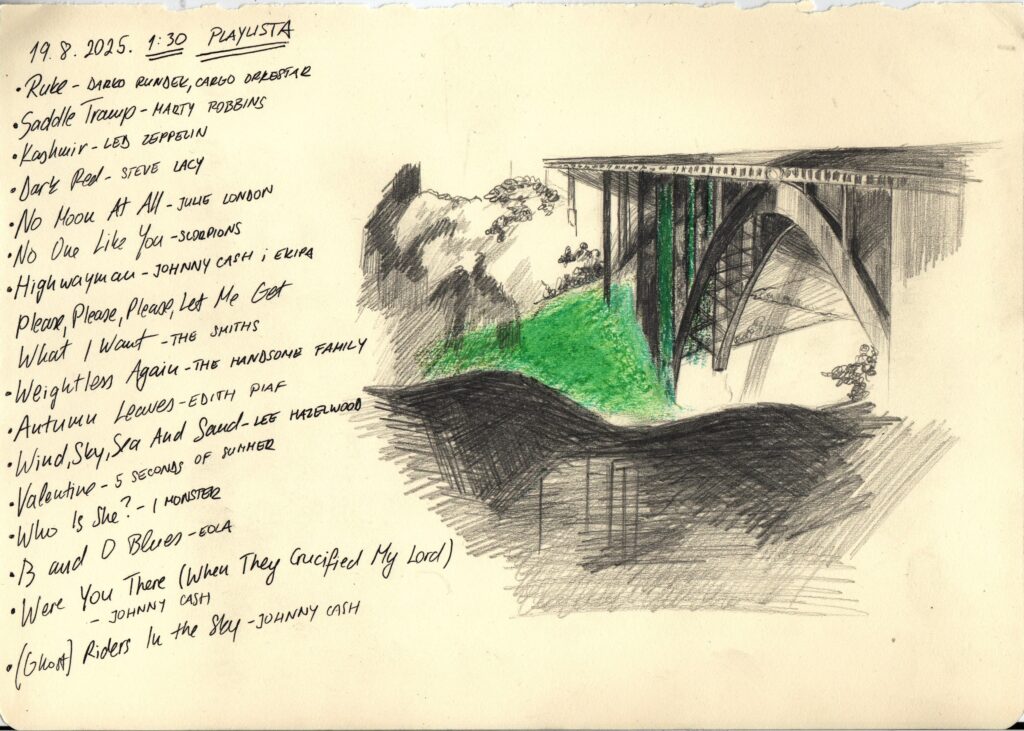

We would, first and foremost, like to give our thanks to our mobile phones, for being the best pieces of equipment a girl separated from her friend could want and need. Leonarda would also like to thank her mentor and professors who involved her into this project, and also her family, Friends Hanging Out (Prijatelji koji se druže) group, her dog Lucy, boyfriend Anes, the city of Ljubljana and, of course, herself. Nika would, beside herself and Leonarda, also like to give thanks to her mentors and professors for involving her in this project, parents (for always having to be reminded of what “that Bauhaus project” is), sea friends, Zagreb friends, both of her grandmothers, Maslenica bridge, and that one pigeon that attacked her in Dubrovnik.

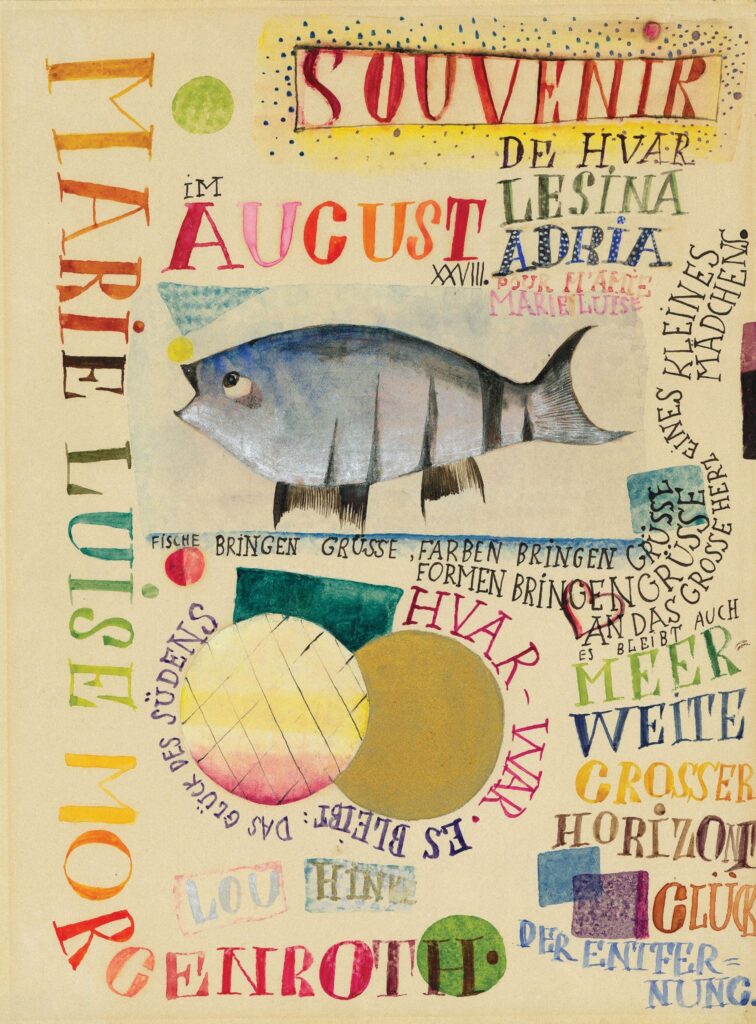

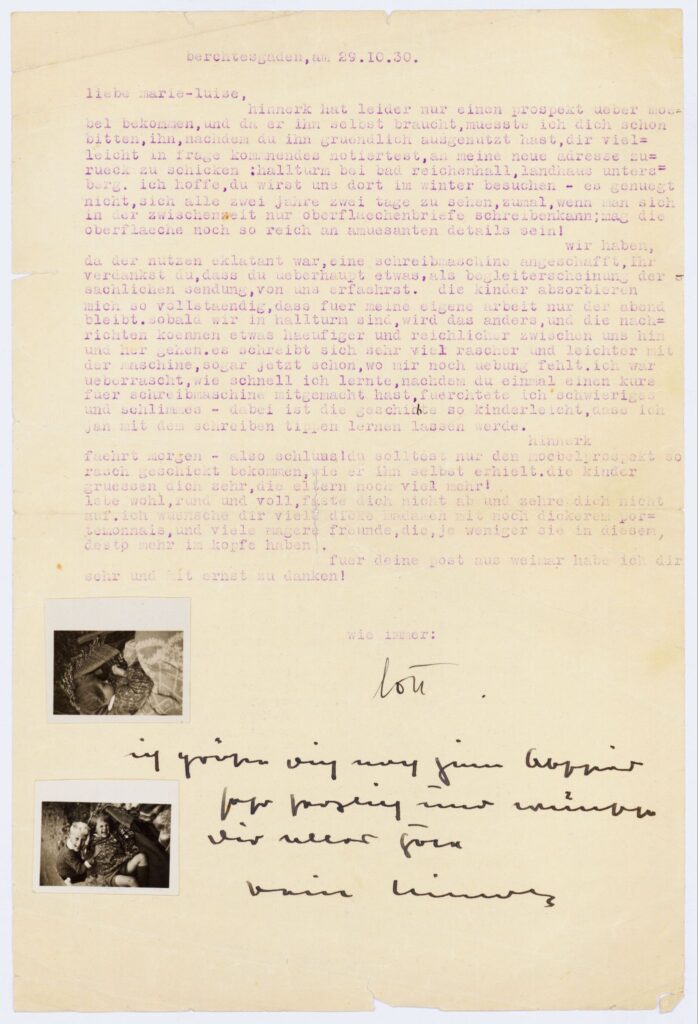

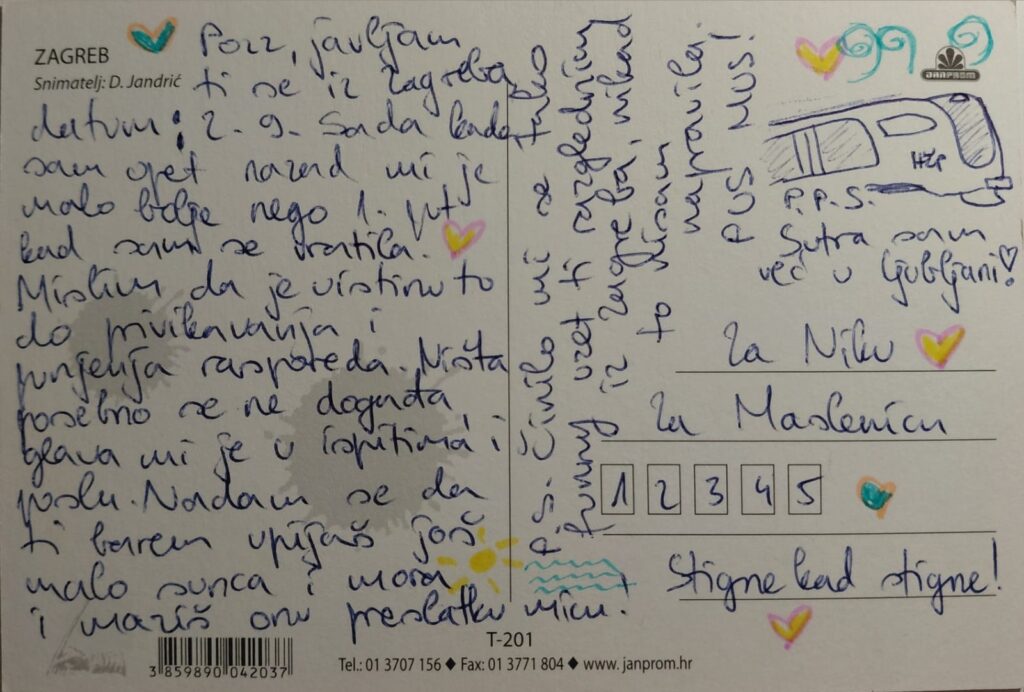

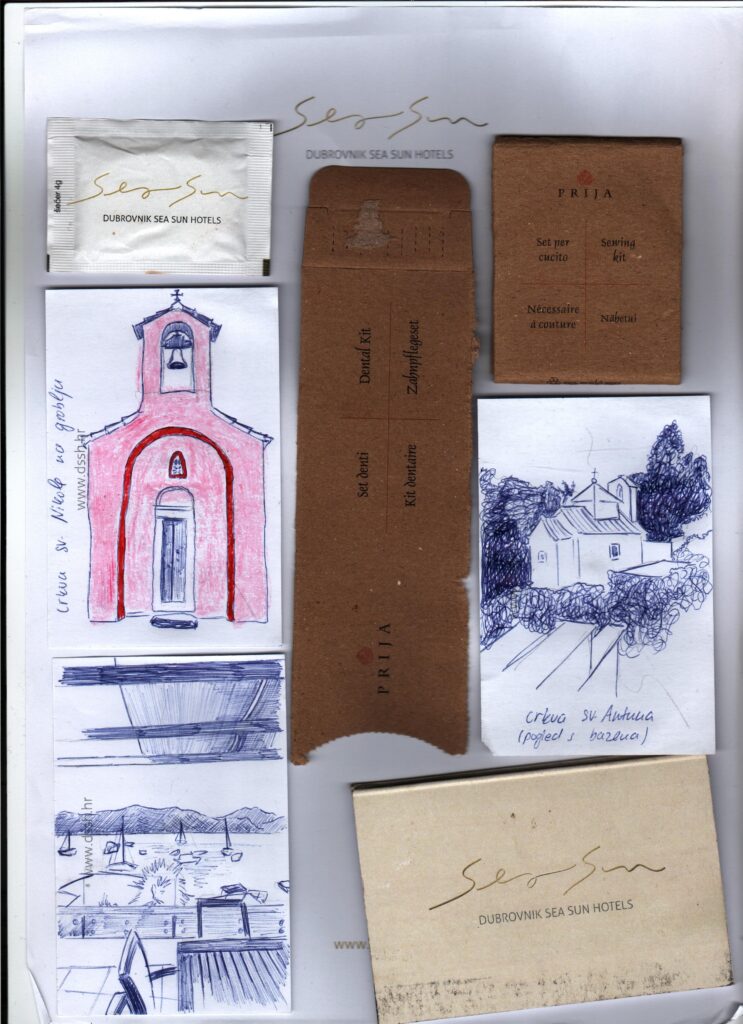

The correspondence between Marie-Luise Betlheim and Lou Scheper records their trajectories, states, and life updates; it consists of two-dimensional drawings and letters through which they maintain their relationship while separated. The transfer of thoughts and emotions, as well as the maintenance of a relationship between two artists through words and drawings on paper, is an invisible intimacy between two people that here becomes publicly accessible. Intrigued not only by the quantity and intensity of the exchanged letters and works, but also by the deep and intimate bond between two friends, this collection inspired us both to explore them further, which resulted in the creation of our own version of a more contemporary archive focused on our personal relationship, that commemorates a three-month period of ‘summer separation’, which each of us spent in different little corners of Slovenia and Croatia, resting and travelling.

Digging into the collection we discovered how Marie-Luise and Lou Scheper, through their letters, in addition to their friendship, very clearly conveyed and marked the time, place and atmosphere, primarily through the very content of the letters, in which dates and different locations are literally recorded, as well as the various contexts within which they originated (travels, studies, war, illness, death). In them, impressions, atmosphere and feelings are described in detail, from separation, loneliness and boredom, to April cold and May heat, all additionally complemented by photographs and drawings. [1]

Since we based our work precisely on their communication and close relationship, we wanted, in our own, more contemporary way, to mark the intimacy and atmosphere of our friendship, as well as our existence in time and different spaces.

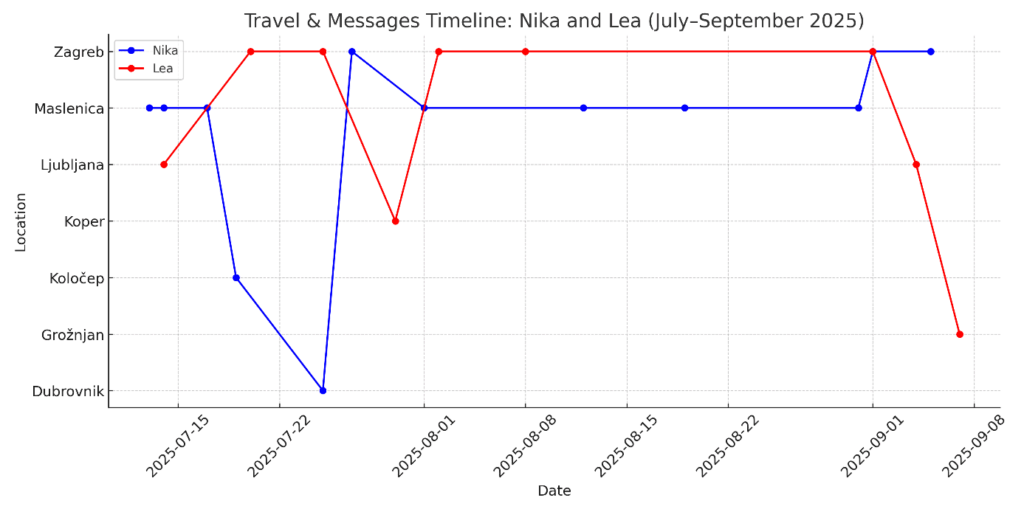

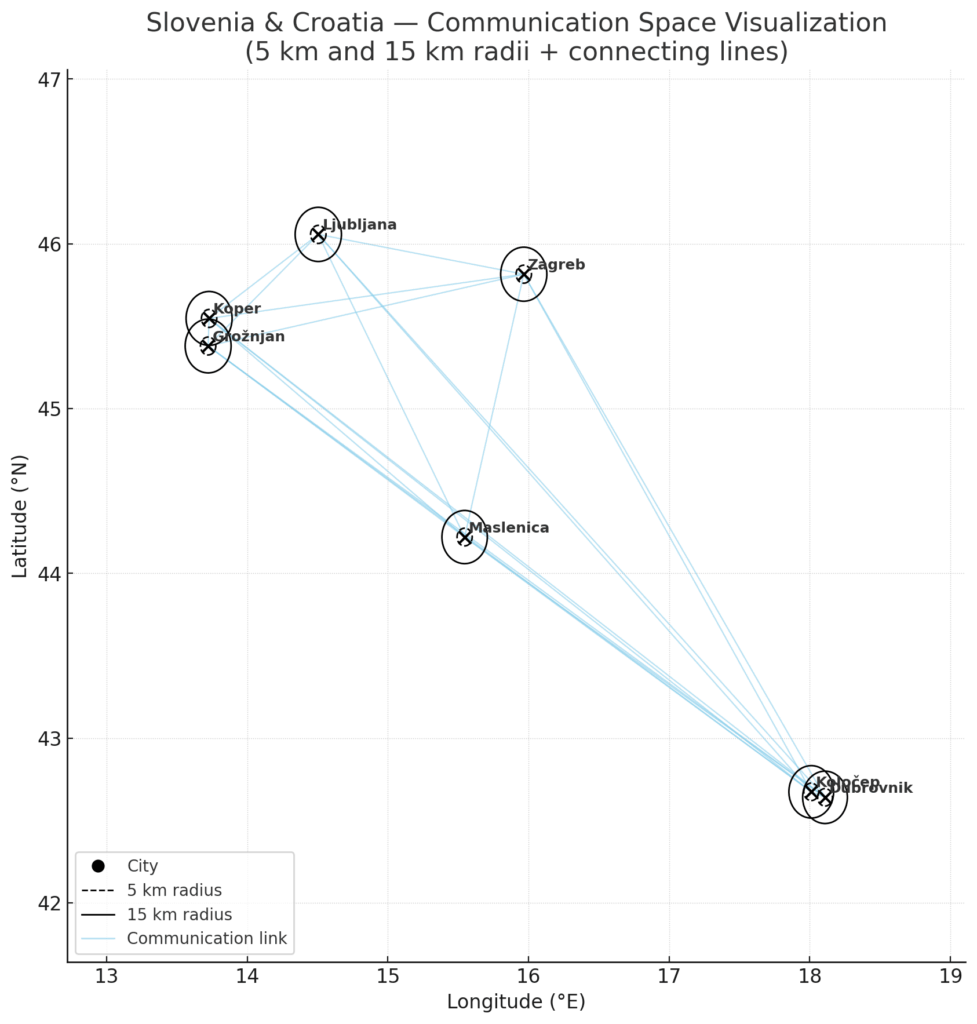

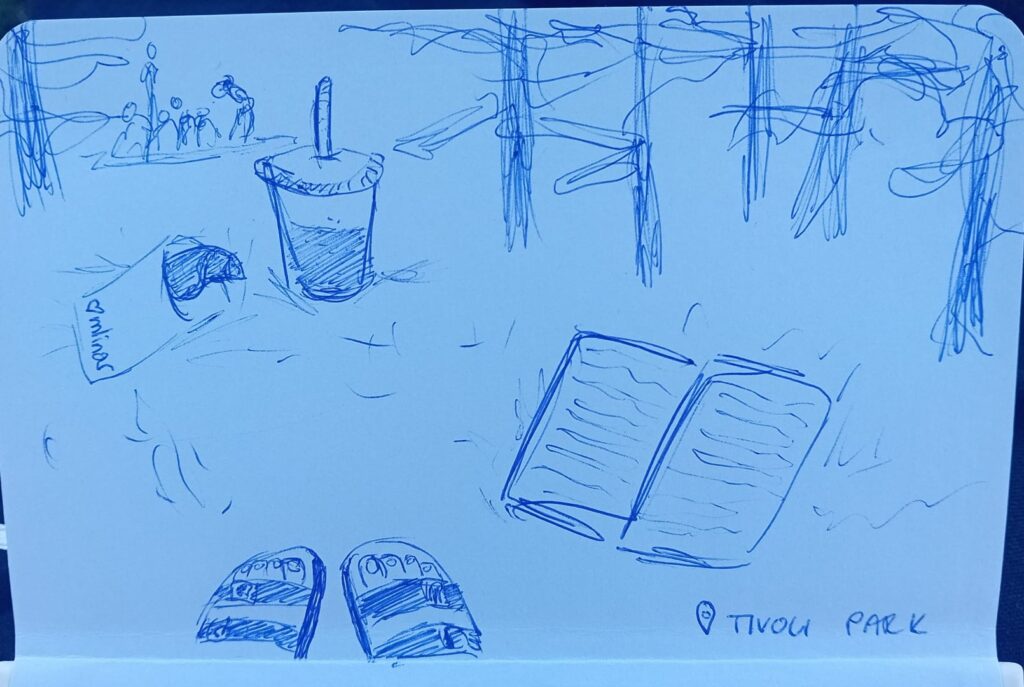

As it turns out, the answer to this question was found right in the back pockets of our jeans, and so we maintained communication via our personal phones, mainly through audio recordings. Later on, we mapped them to the locations from which they were sent, allowing us to visually follow how digital information travels and where and how distant from one another we were at that time. Alongside maps, we also exchanged messages, photos, drawings, playlists, recipes, sculptures, and ready-made objects that were either made, collected or reflected the places we found ourselves in at that moment, capturing it all in a more tangible way.

During the conversation about this project we were guided by the assumption, and by an already forgotten internet article, that in the first half of the 20th century (although telephones were becoming increasingly popular) the prevalent and simplest way of communication was still through written letters. If we had been a little more ambitious (and if the post office in Maslenica had not been open only 3 hours a day), maybe we might have sent letters to each other as well, but as this century brought us new technologies that allow us immeasurably faster and clearer communication, we came to the conclusion that, if we take into account that what we liked about letters was precisely their success in recording places, times and capturing atmosphere, the next best alternative to that process of sending letters would be sending audio recordings (the best alternative, of course, would be calls or video calls, but they are not permanent like letters; they remain in the communication space only in the moment in which they are spoken, and then disappear, never to be heard of again). Drawings and letters between Marie-Luise and Lou are quiet and two-dimensional, limited to the visual and tactile, which draws us to add a new dimension to our version of the exchanged letters — we turn the letter into something audible: speech, the sound of the atmosphere surrounding us in that moment. Audio recordings thus give life and sound to everything that letters express in printed language- time and location, events and contents, while different sounds (which, keep in mind, letters lack), such as tone and rhythm of the one’s voice, greetings from a friend, background sounds of nature or animals, perfectly capture the atmosphere in which the sound recordings come into being. The contents nowadays, thanks to the speed of this kind of communication, do not arrive days, weeks or months later, but become more current than ever before, so that for an exciting or interesting anecdote one has to wait only a few minutes or hours.

To conclude this passage, we would like to refer to The Third Millennium by Croatian art historian Radovan Ivančević, in which he pessimistically predicts that new technologies and ways of communication might alienate people and make direct encounters with other people unbearable.[2] We found that part particularly intriguing because, in a way, technology nowadays enables us to connect with new people and, as is the case of this project, to enrich and maintain intimate relationships with dear people, whom we are then always glad to see in person, over a cup of coffee (or a beer).

Through the process of making this collection we were aware that it would go public, our aim was to make it intimate and interactive, to create space that connects us to others. At times we shared things we didn’t necessarily want everyone to hear, but those fragments were parts of our lives and friendship, so we shared them anyway. Other times we held back, feeling the pull not to share some problems concerning family troubles, college or health. Marie and Lou likely never thought that way, because how would they know that exchange between them would become a precious collection in a museum shared publicly with everyone one day.

From an economics journal: „Privacy is used today in at least three senses. First, it is used to mean concealment of information; indeed, this is its most common meaning today. Second, it is used to mean peace and quiet, as when someone complains that telephone solicitations are an invasion of his privacy. Third, it is used as a synonym for freedom and autonomy.“

(…)

From a sociology journal: „Privacy is the ability of individuals to control the terms under which their personal information is acquired and used“[3]

But privacy is not natural in a way, rather culturally constructed, formed by context and changeable. There is often the tension between individual rights and the collective good. Here arises the question of how something private can become public, and what is the collective good? When we are talking about privacy it is closely tied to political aspects too, because it can reflect value and power.

The collection of Marie and Lou is considered national treasure, marking the artist Marie who lived in Zagreb, and works exchanged from important Bauhaus artists to her, one of them being of course Lou Schepper, but in smaller amount also Farkas Molnár, Paul Klee, Henrik Stefán, Hinnerk Scheper and Kurt Schwerdtfeger. In that sense their works became part of documenting history, telling important stories and sharing photos connected to the Bauhaus school. Here we are torn between national heritage on one side and private intimacy on the other, in which at the end, political word determines considering the private- artists are not alive anymore, they cannot have a say in it, someone else decided for them. And yes, they are not here anymore so what is the big deal with the collection being public? The thing is, that it gives us such an intimate point of view from one or the other author and into their relationship. We can get a feeling that we should not be reading or looking at those letters because that wasn’t their intention in sending those. We can say it is up to each individual to decide should the collection be public or not. But the final say really belongs to those who possess the collection- the archivist, and it can be a constant conversation but also an issue between donors, family, institutions, a country and researchers. The archivists’ job is to share materials and not to hold on to privacy and they bear the consequences.

The collection of Marie-Luise and Ruth Betlheim is different from ours in that way because we are aware from the start about our exchange going public, and we gave our consent. In that way the two of us are making the archive of our own, but we are also the archivists of that collection, the doorkeepers, we decided for this material to be publicly displayed. Considering that in our collection we are using audio recordings, a modern form of communication via WhatsApp, an app, we must also think about all those apps on the internet that we give information to all the time (like Google, Facebook, TikTok). In that way other things we share each day without the intention to be public can become public, if a third person behind those apps decides to, or if we even press the wrong button like consent, when you think about it is kind of a paradox. But privacy in our work is not only digital, we create it through those audio recordings capturing the surrounding sounds, also capturing our physical form in a specific space thus creating a space of communication.

Over the last few months, we have been through a lot of places, and a lot of questions and problems filled our minds, conclusions to which will be drawn up in each of our reviews, that are to be exhibited with all of the voice memos, maps, drawings and other trinkets. For now, we came to realize how important our ongoing communication is, how much we change even during short periods of rest and travel, and how we sometimes hold back from sharing fully, knowing that our own collection will eventually be made public.

[1] „Dear…! Content, I sit on the beautiful Margaret Island and watch how the elegant people of Budapest enjoy their walk; a military band is playing, and all around is water and many boats. I feel comfortable, only it is not nice when I am alone. (…) The building is located on the southern slope of a large hill from which the entire city and the Danube can be seen. It is very hot, but it is wonderful, we are getting tan before our eyes.“—Hinnerk Scheper, a letter to Marie-Luise, May 23rd, 1924

[2] Imagining a person finally and definitively isolated in their room and completely separated in life from the world and from other people – with whom they communicate only indirectly through electronic image and sound – the author predicts that people will not only become alienated, but that their possibilities for direct contact will, over time, atrophy, that they will become immunologically unprotected and psychologically unprepared, and that they will simply no longer be able to endure direct encounter with another person (without shock and disturbance)— Radovan Ivančević, Visual Culture and Art Education

[3] Posner, R. A. (1981). The Economics of Privacy. The American Economic Review, 71(2), 405–409; Culnan, M., & Bies, R. (2003). Consumer Privacy: Balancing Economic and Justice Considerations. Journal of Social Issues, 59(2), 323–342; as cited in: Linda Coon, Mary C. Lacity, Human Privacy in Virtual and Physical Worlds – Multidisciplinary Perspectives, u: Technology, Work and Globalization, Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2024.