The European Mediterranean Academy

A few days after the Reichstag elections of 31 July 1932 that made the NSDAP the largest party in the Reichstag for the first time, the architect Erich Mendelsohn from Berlin and his friend and colleague Hendricus Theodorus Wijdeveld from Amsterdam travelled down the Rhone towards the Côte d’Azur.[1] The journey was the first concrete step towards the realisation of an art academy project that Wijdeveld had pursued for some time and which gained a new direction through Mendelsohn. Wijdeveld, an architect and set designer associated with the Amsterdam School and editor of the art journal Wendingen, had been working for several years on a plan to establish an internationale werkgemeenschap (international working community) near Hilversum. His concept, which he published in 1931, was inspired by the guilds of the British arts and crafts movement and by the Bauhaus.[2]

Mendelsohn seized on the idea of a multidisciplinary educational institution for artists arranged along the lines of a working community but was able to convince Wijdeveld to swap the lakes region of the Netherlands for the azure coast of France and the yellow sun of le Midi. The plan was backed by Mendelsohn’s healthy network of contacts with French politicians and creative artists and his commitment to a united Europe with – as he saw it – the Mediterranean as its historic centre and a bulwark of its collective identity.[3]

[1] The present text is based on the author’s publication Die Europäische Mittelmeerakademie. Hendricus Th. Wijdeveld, Erich Mendelsohn und das Kunstschulprojekt an der Côte d’Azur, Zurich: gta Verlag, 2019. In the following, only quotes and additional information are referenced.

[2] H[endricus] Th. Wijdeveld. Naar een internationale werkgemeenschap, Santpoort: Mees, 1931.

[3] Luise and Erich Mendelsohn maintained close ties with the French embassy in Berlin; Mendelsohn published and presented lectures at European forums.

The name chosen for the school reflects his influence: Académie Européenne Méditerranée. “We are founding an ‘academy’”, it said in a promotional flyer, “for after a century of experimentation, the elements of a new style have become manifest. We feel drawn to the Mediterranean for this ocean forms the foundation of European culture.”[4] The agenda of the European Mediterranean Academy – with which it went beyond its reference object, the Bauhaus – entailed balancing modern art and its synthetic links with the values of the classical Mediterranean tradition.

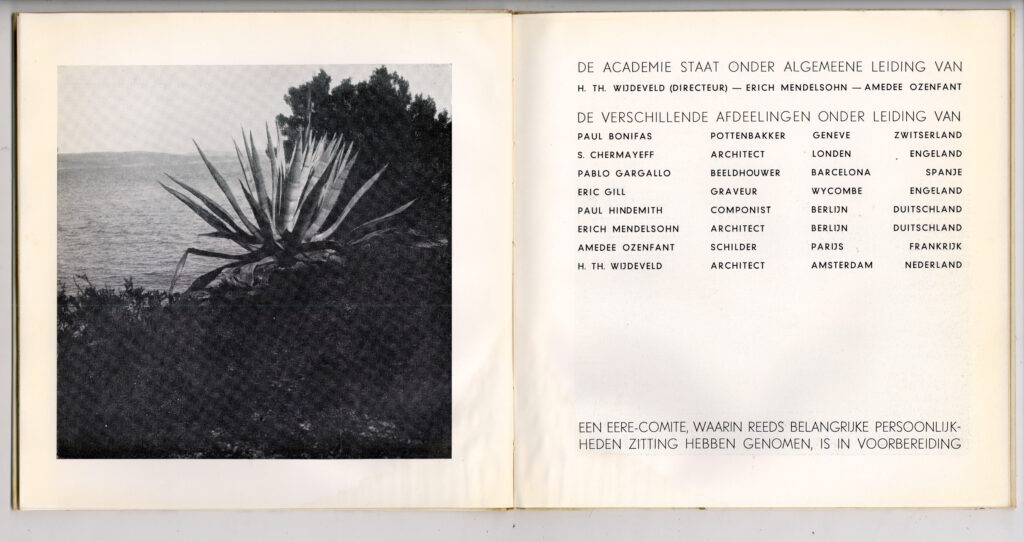

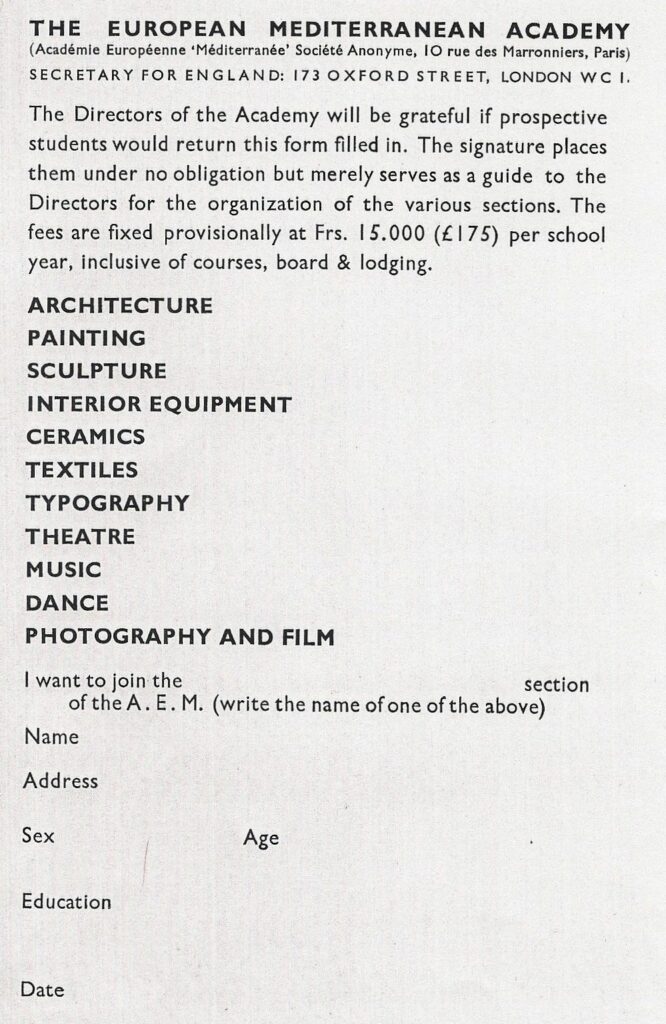

During their ten-day tour along the Côte d’Azur in August 1932, Wijdeveld and Mendelsohn were already on the lookout for possible locations for the project.[5] A joint-stock company was to provide the necessary funding. To attract shareholders, a wide-ranging advertising campaign featuring talks, articles and the first information flyers was launched before the end of the year. Stationery and an expensive hardback advertising brochure published in English, Dutch, German and French (500 copies of each version) followed in early 1933.

[4] Hendricus Th. Wijdeveld. Academie Européenne Méditerranée, four-page printed publication in Dutch, Amsterdam, [probably January] 1933, author’s own archive.

[5] Both Erich Mendelsohn and H. Th. Wijdeveld reported back almost daily to their wives, who had stayed at home. The Wijdeveld family’s correspondence is found in the Wijdeveld Archive, Het Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam. The correspondence between Erich and Luise Mendelsohn is available online at: http://ema.smb.museum/de/briefe.

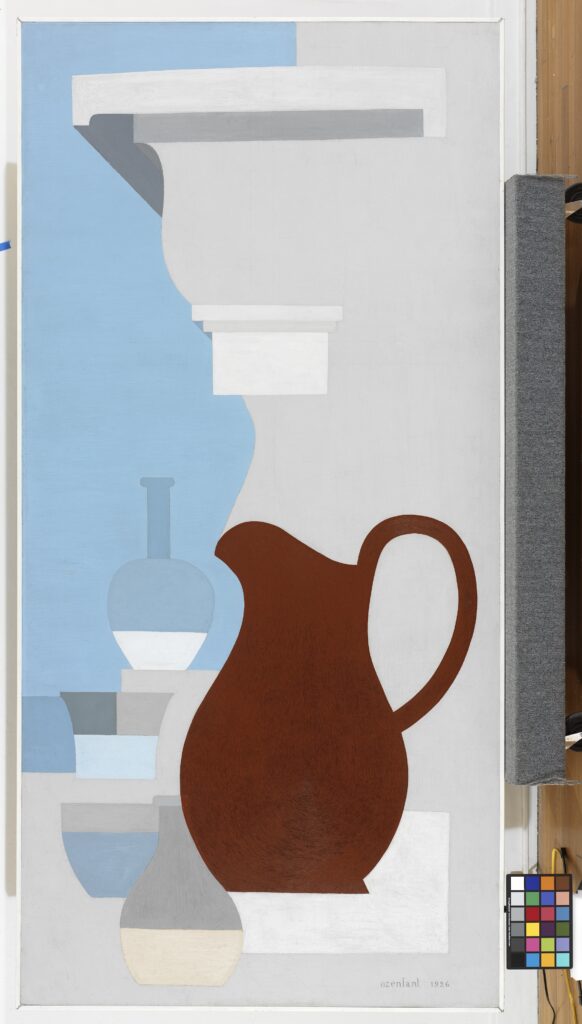

At the same time, potential teachers were contacted, and by February 1933, a respectable group of artists of international standing had been brought in. First of all, the French painter Amédée Ozenfant was secured as third director. With his inclusion in the project, specifics of French modernism such as purisme and retour à l’ordre (the return to order) were activated, both of which are located in the literary and historic-philosophical context of la pensée de midi (Mediterranean thought) and longue durée (long duration). Here, Ozenfant exemplifies a return to the timeless classical culture of the “Mediterranée”.[6]

Through Ozenfant’s personal contacts, Paul Bonifas and Pablo Gargallo were added to the team. The former was envisaged as head of the ceramics workshop. In the early 1920s, the Geneva-born master potter had served as general secretary of the journal L’Esprit Nouveau published by Ozenfant and Le Corbusier. The Spanish sculptor Gargallo, who had shared a studio with Pablo Picasso in Barcelona and now had a studio in Paris, was chosen to establish the sculpture department.

Other artists were brought in by Mendelsohn and Wijdeveld; two creatives from England confirmed their participation. Serge Chermayeff, the prospective head of the interior design department, was a colourful, eclectic figure, a native of Chechen living in London who had made his mark as an interior architect and designer. Eric Gill was enlisted to teach typography. He was embedded in the traditions of the arts and crafts movement and had founded three craft communities. His reputation as a sculptor and typeface designer extended far beyond his native England. For the music department, negotiations began with Paul Hindemith, who from 1927 had taught composition at the academy of music in Berlin. With these five artists, the process of choosing the academy’s future heads of department was over, at least for the moment. The three directors themselves aimed to take charge of the theatre department (Wijdeveld), the painting department (Ozenfant) and the architecture department (Mendelsohn). Staff for the additional workshops envisaged for dance, textiles, photography and film would be found at a later stage.

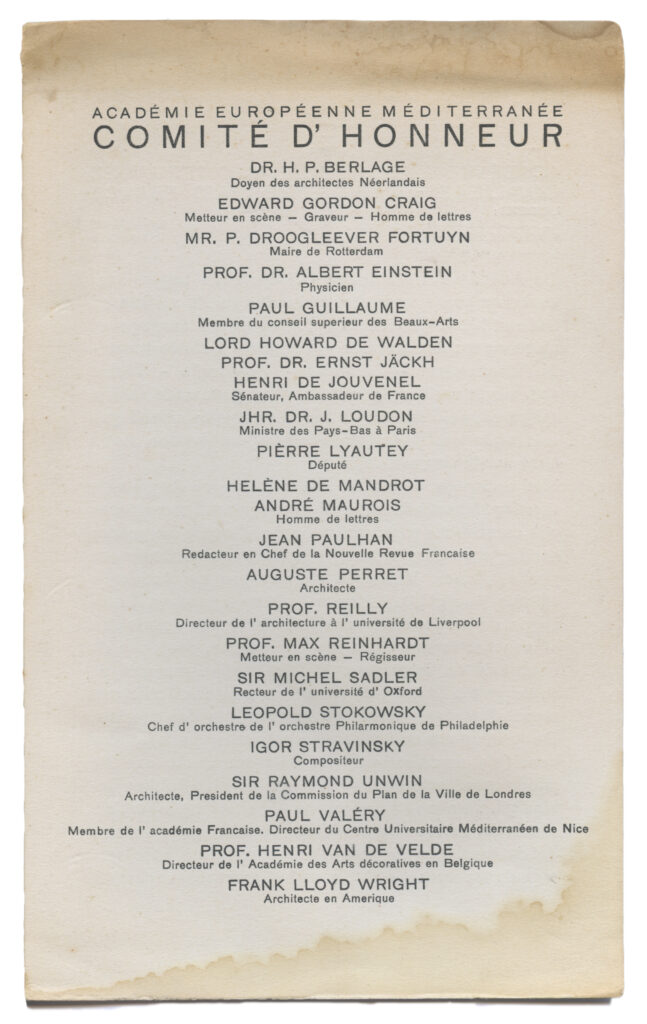

Even more impressive than the list of future teachers are the names of the members of the 24-strong honorary committee. Headed by Albert Einstein, the members included important men from the worlds of art, politics and science and a single woman, the initiator of CIAM, Hélène de Mandrot de Sarraz. In addition to an international “old guard” of renowned architects including Hendrik Petrus Berlage, Auguste Perret, Charles Herbert Reilly, Raymond Unwin, Henry van de Velde and Frank Lloyd Wright, this committee included the English set designer Edward Gordon Craig, the Austrian theatre director Max Reinhardt, the French poet and essayist Paul Valéry and the musicians Leopold Stokowski and Igor Stravinsky.

[6] Cf. Amédée Ozenfant. Art: I. Bilan des arts modernes en France: littérature – peinture – sculpture –architecture – science – religion – philosophie. II. Structure d’un nouvel esprit, Paris: Picart, 1928.

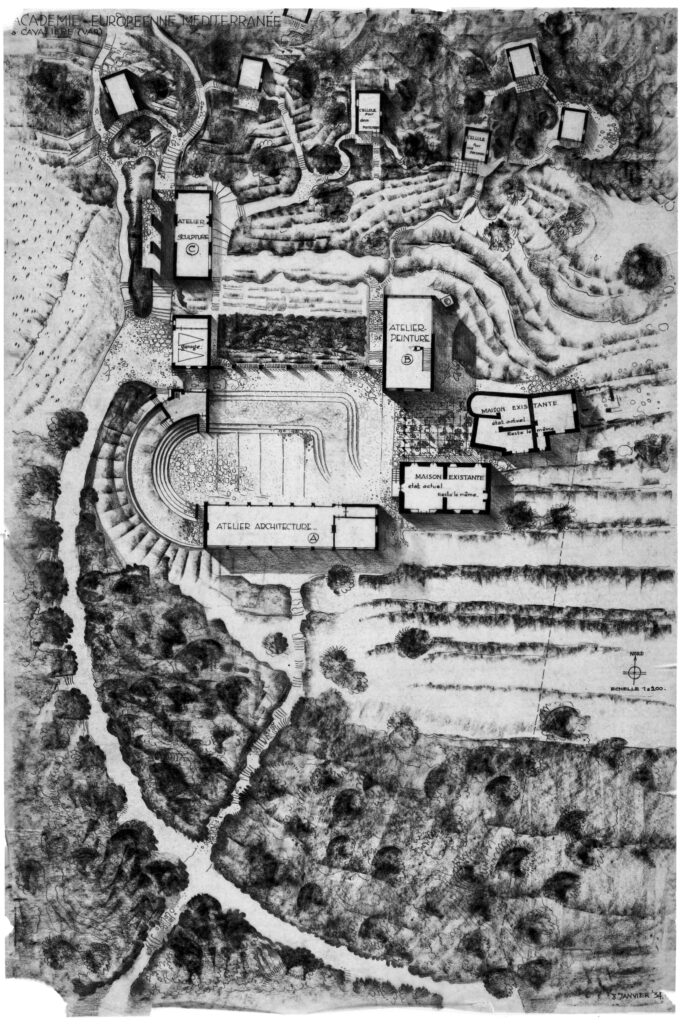

With such an array of renowned figures, who promised both intellectual anchorage and international connections, the subscription process for shares was initially highly successful. In mid-1933, in Cavalière between Le Lavandou and Saint-Tropez, a “wonderful 104-hectare plot” was purchased, “away from the distractions of the Riviera, yet still connected to the international lines of communication”.[7] Enrolment forms were sent out throughout Europe a short time later. The tuition fees including bed and board for the three-year period of education were set at 45,000 Francs. The provisional curriculum of the academy, which was announced for 1 March 1934, was at first limited to the architecture class.

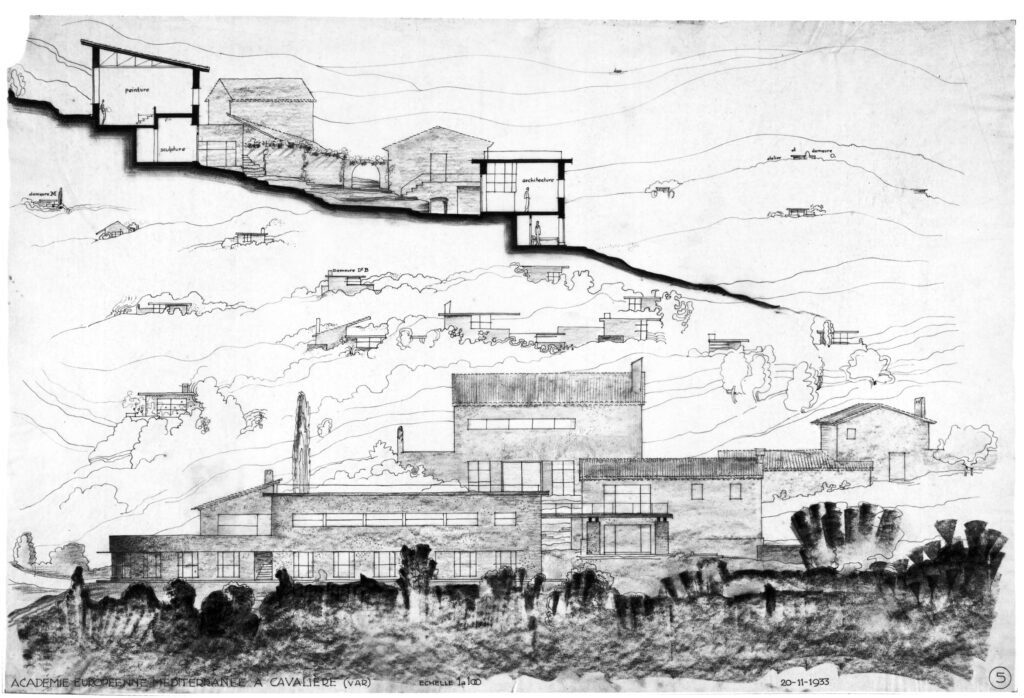

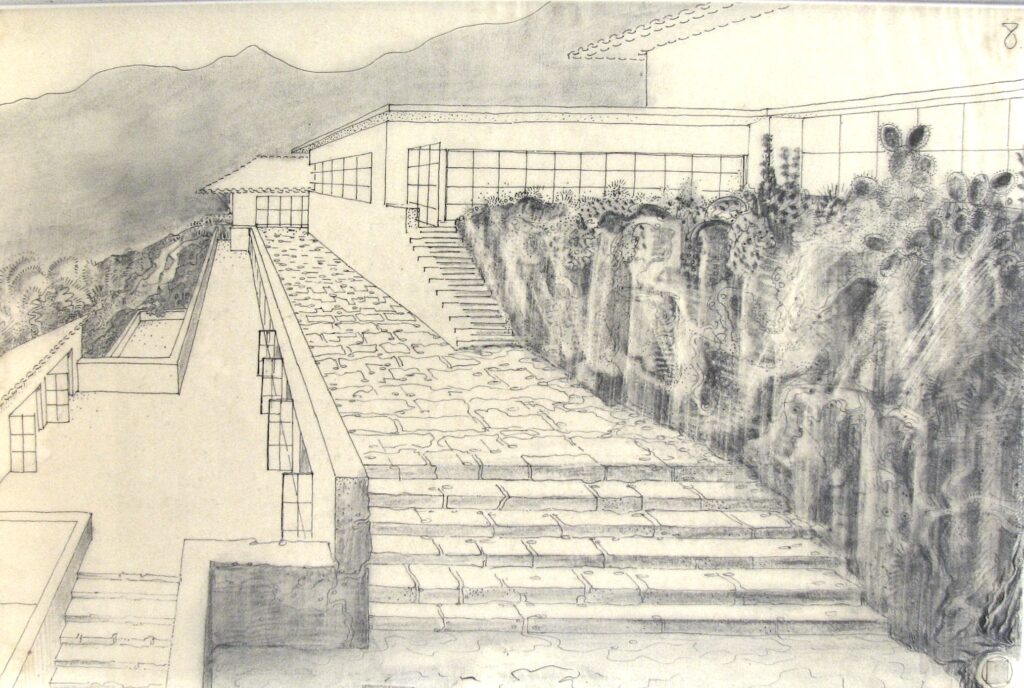

As with Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin Fellowship, the original concept for which was drafted with Wijdeveld’s involvement, the students were offered to participate in the construction of the building. Wijdeveld’s design drawings, which he completed in late-1933/early 1934, were stylistically aligned with the two simple houses already standing on the site, which were built of un-rendered quarry stone gable roofs clad with tiles. Assimilating the typical local anonymous architectural style, Wijdeveld placed his studio and residential buildings in an informal arrangement nearby. For the central point of the campus, he designed a meeting place with an open-air stage.[8]

[7] [Hendricus Th. Wijdeveld, Erich Mendelsohn and Amédée Ozenfant (Eds.)]. The European Mediterranean Academy, English information prospectus, mid-July 1933, Erich Mendelsohn Archive, Kunstbibliothek, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Preußischer Kulturbesitz.

[8] The existing design drawings show various planning stages. All plans are found in the Wijdeveld Archive, Het Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam.

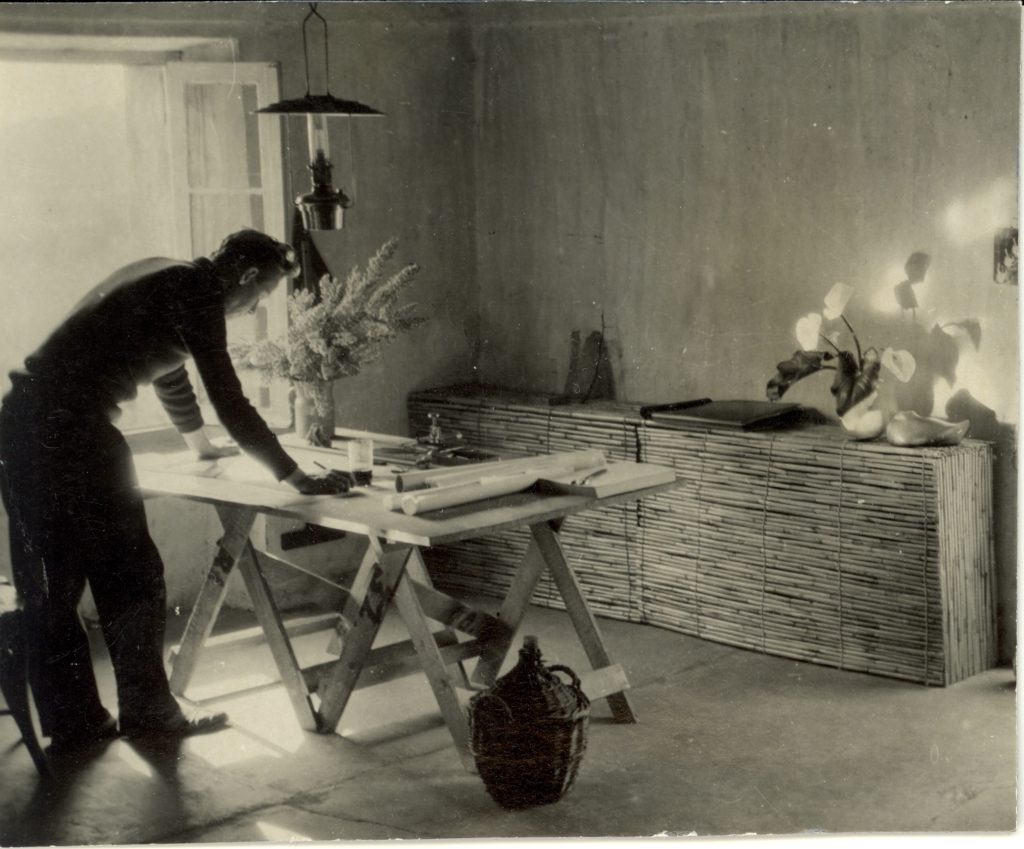

As announced, a small group gathered in Cavalière on 1 March 1934 to get the European Mediterranean Academy project up and running. None of the teachers who were originally enlisted were present, not even Mendelsohn, who was absorbed in the new architecture office in London which he had established together with Serge Chermayeff. Wijdeveld was joined on the overgrown plot of land by his wife Ellen and other family members, a few students, the landscape architect Reinhold Lingner, who would go on to establish a career in the GDR, and his wife, the art student and renowned photographer Alice Kerling.[9]

Barely five months after their arrival, the small group’s modest efforts to transform the Mediterranean wilderness into a Garden of Eden were foiled by an extensive, devastating fire. Wijdeveld described the look of the grounds after the fire as a “battlefield”.[10] In a remarkable way, the fate of the academy seems to have pre-empted the historic events.

[9] A limited amount of material on Reinhold Lingner and Alice Kerling’s 14-month stay in Cavalière is held by the estate of Reinhold Lingner, Leibniz Institute for Research on Society and Space, Erkner.

[10] Hendricus Th. Wijdeveld, letter to Erich Mendelsohn with copies to Jean Ehrlich, Cornelia Langelaan-Stoop, Clément Antoine Wertheim Aymès, Amédée Ozenfant and Ossip Bernstein, Cavalière, 18 July 1934, Erich Mendelsohn Archive, Kunstbibliothek, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Preußischer Kulturbesitz.

holds the professorship of History of Art and Architecture at ETH Zurich. After studying art history and philosophy, her dissertation dealt with Erich Mendelsohn’s buildings and projects in British Mandate Palestine. Ita Heinze-Greenberg has taught at the Technion in Haifa as well as at the Bezalel Academy in Jerusalem, the University of Augsburg, the TU Munich and the TU Delft. She has been a Senior Scientist at the Institute for History and Theory of Architecture at ETH Zurich since 2012. Ita Heinze-Greenberg also works as a freelance author. Ita Heinze-Greenberg’s research interests and publications include 19th and 20th century architecture with a focus on new building in the Mediterranean region, especially in Israel, in the context of migration research, identity constructions and nation-building. In 2019, she has published with the Zurich-based gta-Verlag “Die Europäische Mittelmeerakademie. Hendricus Th. Wijdeveld, Erich Mendelsohn and the Art School Project on the Côte d’Azur”.