Experiment as method: The tradition of Bauhaus Pedagogy as the Academy of Applied Arts in Zagreb (1949–1955)

The Academy of Applied Arts[1] (AAA), which operated in Zagreb from 1949 to 1955, is a paradigmatic example of a radical pedagogical model based on the Bauhaus tradition. The context in which it operated in socialist Yugoslavia of the 1950s confirms the inadequacies of conventional interpretations of ‘centre’ and ‘periphery’ confronting them with the complexity of simultaneous discourses of cultural production. The reasons for this simultaneity likely lie in the period’s cultural and sociological characteristics. These are recognisable in the programme’s idea of a synthesis that assumed the interpenetration of architecture, visual art and the design of functional objects in order to include all kinds of creative interventions in the construction of a new, plastic reality. This was the moment when design became an omnipresent topic, present in everything from media debates, propaganda exhibitions, visual communications and the quality of everyday life – design became a synonym for democratisation, modernisation and general social progress.

[1] The Croatian name is Akademija primijenjenih umjetnosti, often abbreviated to APU.

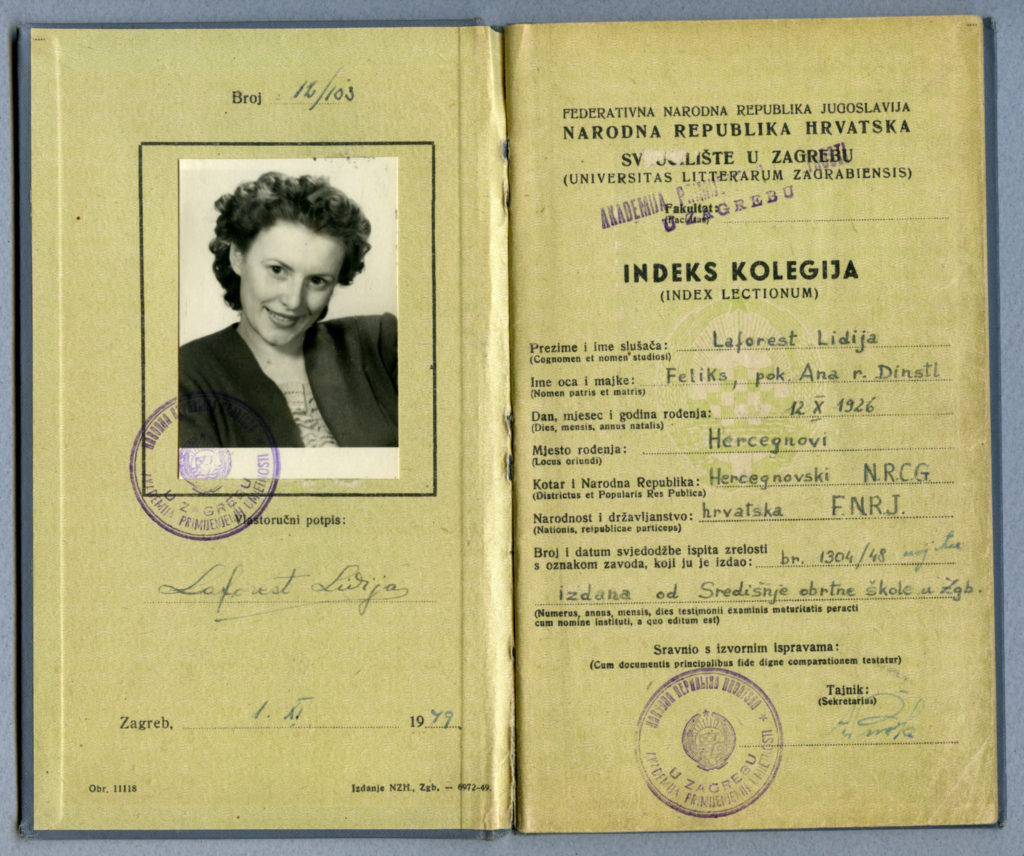

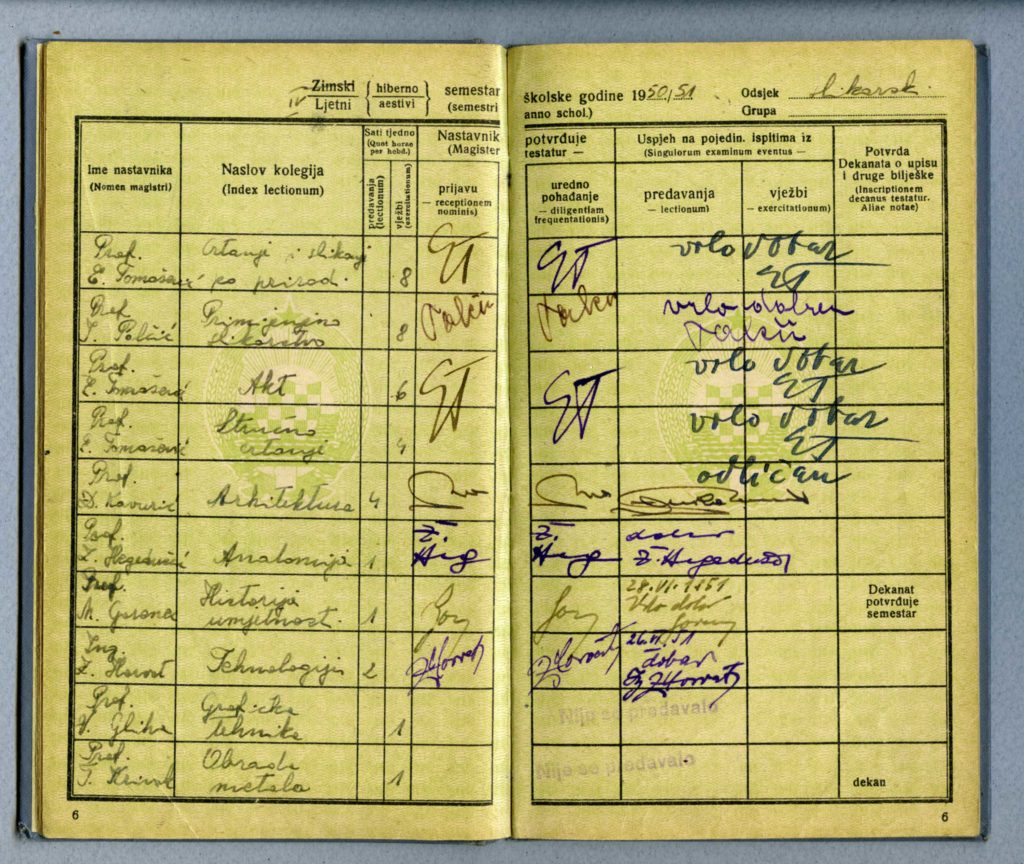

The Zagreb Academy of Applied Arts was part of a tradition stretching from the Bauhaus and the New Bauhaus in Chicago to the Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm (HfG), and this was manifest in its theoretical foundations, structure and teaching methods. The common point of departure was the new social role of design, i.e. the political implications that emerge from design, and this ultimately led to the closure of these institutions. A generation of architects, artists and designers were instrumental in the founding of the Zagreb Academy of Applied Arts and in its activities and public reception. This generation matured professionally amid an atmosphere marked by the post-war reconstruction and the utopian projects within socialist society that followed the motto ‘The future is now’. They included members of the group EXAT 51, lecturers with experience in similar educational institutions and established authors who, being politically and socially engaged professionals, helped forge the cultural policies of that time.[2] ‘Industrial production’ was the key word directing AAA’s programme. It was considered the starting point for design’s ideological dimension in a socialist society because it shaped ‘a person’s visual surroundings’ and ‘social meaning’. In contrast to the art academies’ elitist profile, AAA emphasised openness from the start: students from all parts of Yugoslavia and the wider region came to study there. Often, they transferred from the foundational study programme to one of the architectural faculties or other academies, and open studios were used as a teaching method. The 70 AAA programme participants included around 30 female students, yet the proportion of women varied dramatically in certain departments: only women studied in the textile department; in the architectural department, four of the 13 enrolled students were women; while in the sculpture department, not a single woman graduated. These differences were less pronounced in the participants’ later professional activities, as the careers that the AAA programme participants chose had a markedly interdisciplinary character.

[2] Besides Vjenceslav Richter, who worked intensively on theoretical and practical issues related to plastic synthesis, Zvonimir Radić played a key role in articulating EXAT 51’s theoretical basis. This is also confirmed by a comparative analysis of Radić’s later texts that especially include ideas such as ‘design in the context of a plastic reality’, which formed the framework for his theoretical discourse.

The Bauhaus’s legacy at AAA is manifest in its didactic system based on a preparatory course modelled on the preliminary course and the specialist teaching programme in the later years at the school. The teaching method was grounded in collective work by students and teachers, and instead of traditional lectures, teaching took place in working groups. As part of the workshops in woodwork, textiles, metal, and wall painting, students solved specific tasks, that is, they put into practice skills acquired at the level of experimental teaching models.[3]

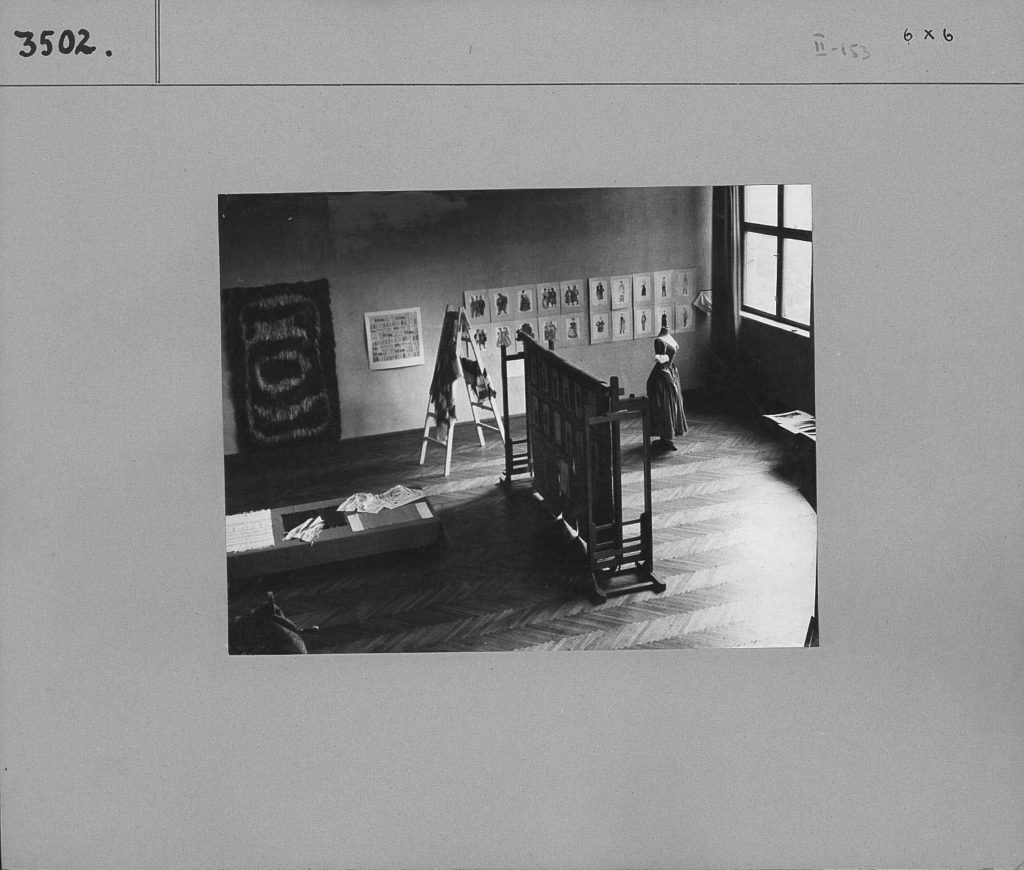

The exhibitions of student works organised as an integral part of AAA’s teaching programme give a favourable impression of the educational model’s interactive approach. After the first year, the study programme continued in the architecture, textile, painting, ceramics and sculpture departments, followed by further specialisation in the third and fourth years. The teaching programme was reorganised as early as 1951/52 with the goal of introducing more industrial design. A new core study programme named Produkt (product design) was introduced. It was a joint programme for all departments from the second year of study, intended to establish stronger collaborations with industry. One additional sign of this reform was a new set of terms used in the teaching programmes.

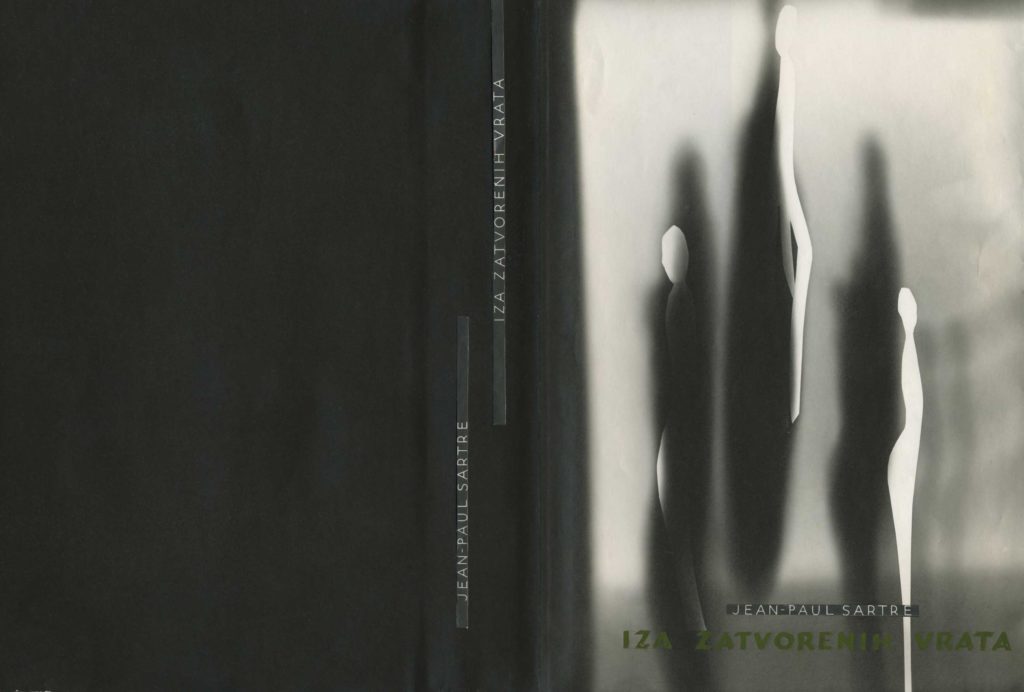

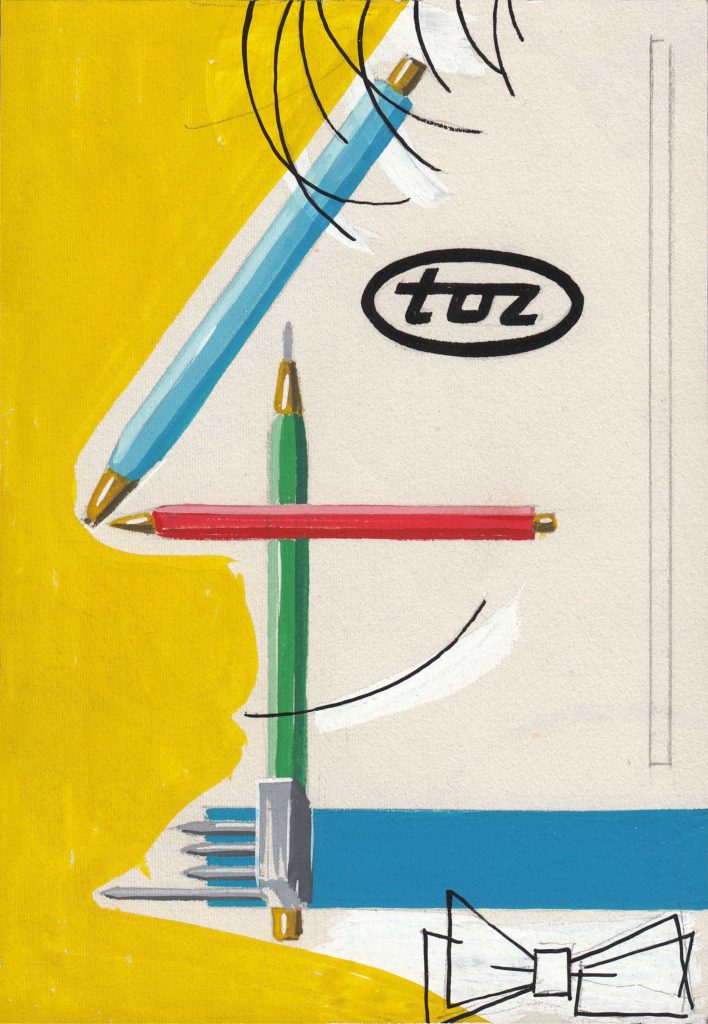

In the architecture department, the task was to produce prototypes for the furniture industry and complete interior-design projects. At the same time, graphic designers made poster designs, packaging and book covers; ceramicists made prototypes for the electrical industry and for the ceramics and porcelain industry; students in the textiles department made prototypes for the textile and clothes industry; the sculpture department engaged in product design from simple projects like making drinking glasses to complex projects such as sewing machines while students in the fine arts department solved tasks that called for artistic interventions in the public sphere.

[3] Undated document from AAA’s initial activity phase. The documents on the AAA teaching programmes, lecturers and programme participants have been partly preserved in the Archives of the Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb.

Students were also included in the public debate, which resulted in a series of radical changes to certain departments’ teaching programmes at the end of 1952/53; from the introduction of new subjects to changes in how master’s theses were produced.[4] Links to Bauhaus’s educational model were also manifest in the core teaching on architectural topics common to all departments, where by solving project tasks, the students were encouraged to creatively explore space in its function as a contextual framework in the design process.

Construction and project design dominated the architectural studies’ teaching programme in terms of the number of hours of lectures and exercises. It was taught by the architects Đuka Kavurić and Vjenceslav Richter, and the teaching plan for the study programme’s fourth year also covered subjects like spatial description, applied psychophysiology and history of art, while the titles of subjects covered in the study programme’s fifth year included synthesis (‘the unification of all artistic forms in space’), contemporary aesthetic and artistic theories, representation, project equipment and a photo seminar, all of which pointed to an even more pronounced tendency towards interdisciplinarity. The photo seminar was not only attended by students, but also by AAA teachers. According to statements made by the programme leader, Mladen Grčević, it was modelled on László Moholy-Nagy’s lessons, i.e. the Bauhaus programme of exercises that intended to familiarise participants with the applications and visual effects of manipulated photographs.

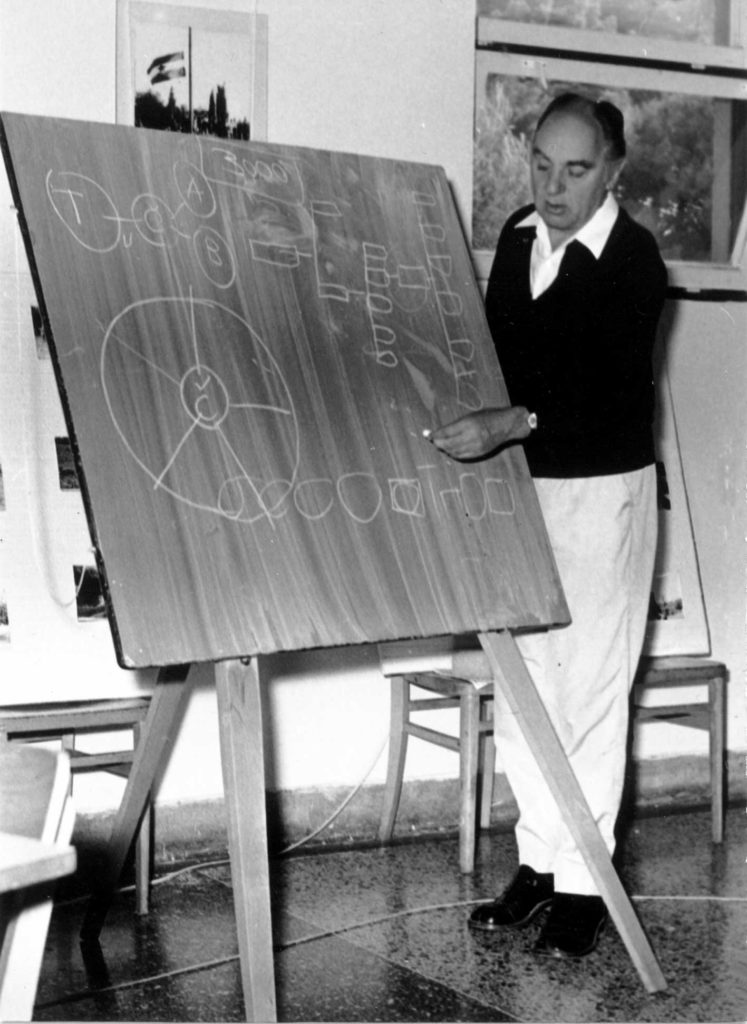

Analogies with avant-garde experimental educational models were most visible in Zvonimir Radić’s teaching in the architectural department. Manuscripts, handwritten lecture notes and other documents[5] evince exceptional competences in architectural theory, the theory of space and visual perception and a basic familiarity with modern and avant-garde art and design. Radić was convinced that the Bauhaus’s significance in shaping the contemporary world was immeasurable because the Bauhaus fearlessly accepted machines as a means of artistic expression, confronted the problem of ‘good design’ in mass production and consumption, overcame the gulf between industry and artists and smashed the hierarchical division between high and applied art.[6] The syllabi for Radić’s subjects underpinned the theoretical basis of the AAA’s programme: apart from texts by László Moholy-Nagy, some of the most indispensable sources included publications by Nikolaus Pevsner, Sigfried Giedion and Max Bill.[7]

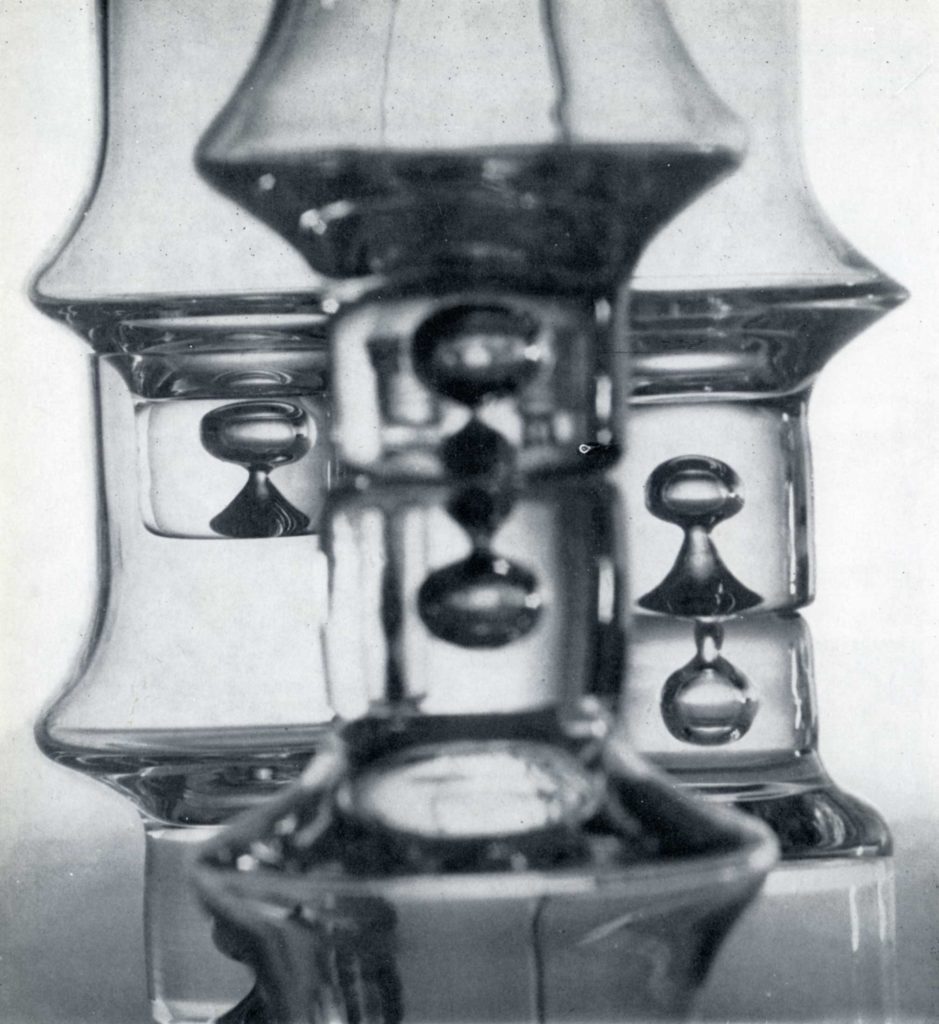

The book Vision in Motion by László Moholy-Nagy was one piece of literature to which Radić would constantly return. It was not only Radić’s personal manifesto, but also a synthesis of his educational project to which he devoted his entire professional career. A comparative analysis of texts points to the analogous thesis on the role of industrial design in technological development and improving quality of life. One illustrative example is the teaching of the subjects ‘designing industrial products’ and ‘the contemporary spatial concept’. Students produced freely designed sculptured objects based on exercises in space and volume designed to inculcate the free development of inventiveness. Conceived as a preparatory exercise in mastering basic principles in the design of functional objects, ‘hand sculptures’ were associated with an organic, ergonomically based design and a sensibility for a material’s specific properties. We can find an analogous example in the ‘spatial modulators’, exercises intended to develop a structural approach to spatial design which drew on the teaching methodology of the Institute of Design in Chicago.

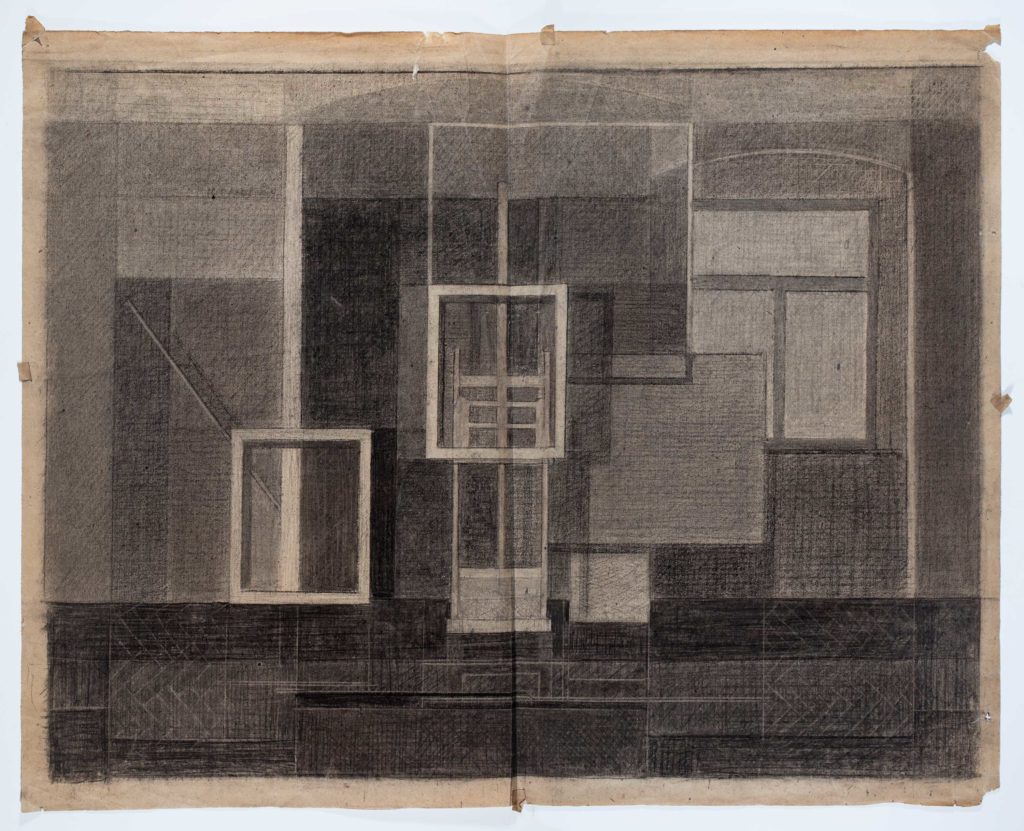

The head of the fine arts classes, Ernest Tomašević, employed a tripartite structure in his teaching programme: observation (noting; studies and analysis of the nature of materials), representation (conceptualising; descriptive geometry, techniques for constructing and drawing plans, models and constructions) and composition (linking up the theory of space, theory of colour and theory of drawing).[8] As part of the lessons, the students would use a template of empty frames arranged in front of wall coverings, upon which they assembled their own compositions. The main emphasis was on liberating creativity by researching forms, surfaces and colours as part of a defined programme, with work ranging from the abstract towards solving specific design problems while keeping in line with the principle that all students work on the same project task.

The final part of the exercise was an exhibition of works and a debate. This method was also similar to Josef Albers’s Bauhaus model exercises in perceptual understanding. The analogue principles were applied to modelling volumes in space such as using wire to cut through clay or nudes made from sheet metal while an equal amount of attention was paid to the positive and negative aspects of the space, to the relations between filled space and empty space. More complex tasks presented in the later years of the study programme, such as the simultaneous display of a body or object such as a bucket of water in various positions, were wonderfully validated soon after in stage design and in animated film.

[4] Unsurprisingly, independent work on the project with minimal teacher interventions was required to produce a master’s thesis.

[5] Preserved as part of Zvonimir Radić’s legacy, made available to the author courtesy of Mrs Nada Radić.

[6] According to Zvonimir Radić’, this occurred when the section for industrial design was founded at the Association of Fine and Applied Arts in Croatia in 1951. The unpublished handwritten manuscript is part of Radić’s legacy.

[7] The literature that Zvonimir Radić used the most included Vision in Motion (Chicago, 1947) and The New Vision (New York, 1947) by László Moholy-Nagy, Giedion’s titles Space, Time and Architecture (Cambridge, Mass., 1941) and Mechanization Takes Command (Oxford, 1948), Pevsner’s book Pioneers of Modern Design from William Morris to Walter Gropius (1936), Language of Vision (Chicago, 1944) by György Kepes, the 1939 monograph Bauhaus 1919–1928 by Herbert Bayer, Ise and Walter Gropius (New York, 1938), Art and Industry (1919) by Herbert Read, Max Bill’s texts and, from the 1960s onwards, texts by of Tomás Maldonado, Giulio Carlo Argan, Bruce Archer, and Misha Black.

[8] Prof Ernest Tomašević. Općenito o radu srednje Škole za primijenjenu umjetnost i APU – Zagreb, p. 1. Undated text, Archives of the Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb.

Analogies with teaching concepts at the Bauhaus were also present in the teaching programmes of the head of the textile department, Branka Hegedušić.[9] Within the textile department, in the third, fourth and fifth year there was a unit for theatre costumes. The theoretical component included all relevant problem areas in costume design, from studies of texts, librettos, choreographies and directing to the psychology of colours. The practical component included ballet studies and theatre dressmaking, and students attended performances and even independently produced costumes for shows on the repertoire, researching colours in front of the film camera in black and white, as well as techniques for filming in colour.

They also completed practical work in film studies and became familiar with contemporary theatre and film ‘from the realistic to the abstract’ in their final year of study, which attests to the teaching programme’s experimental character. In the teaching programme for fifth-year students in the textiles department, lectures were provided on the theoretical foundations of design like those provided by Zvonimir Radić. There was a separate unit on the ‘influence of the Werkbund Institutes on our applied and industrial art’. Subjects from the fields of art science, the science of styles, the history of art and the general subjects of psychology and psychophysiology comprised separate units. Part of the teaching was carried out in collaboration with the theatre academy where the students attended lectures on the history of theatre while the curators of the Ethnographic Museum and the Museum of Arts and Crafts in Zagreb participated in classes on the history of costumes.

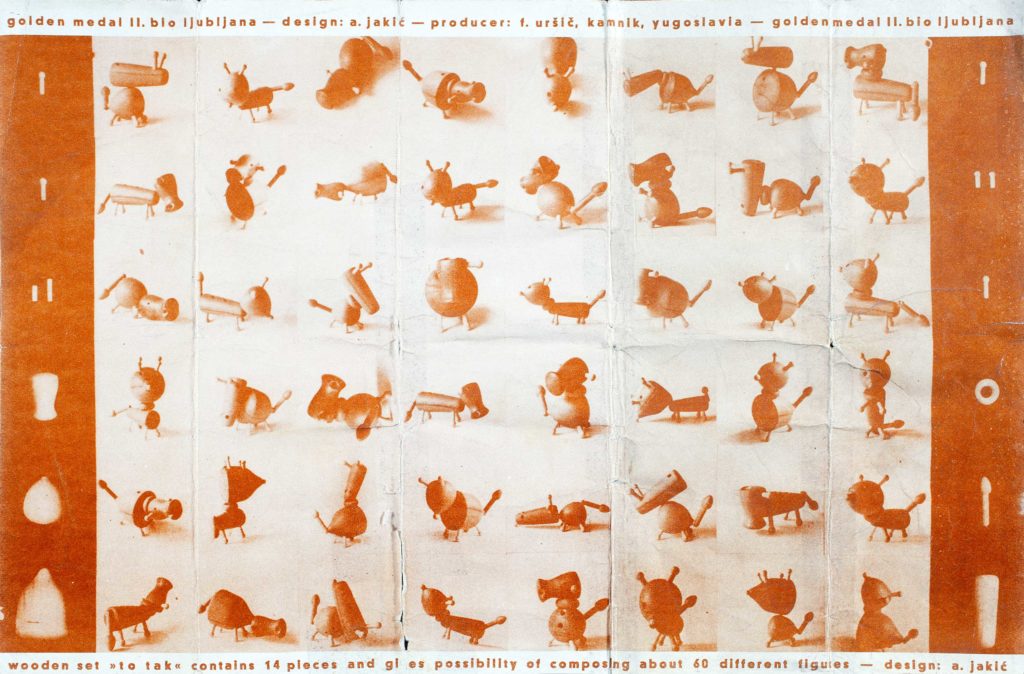

The interdisciplinarity of the experimental programme at the Academy of Applied Arts exemplifies in the very best way the works of Zlatko Bourek, Zvonimir Lončarić, Ante Jakić, Vasko Lipovac, Ordan Petlevski, Jagoda Buić and numerous other students who cannot be unambiguously identified by a single art medium in the traditional sense. After studying fine arts in Ernest Tomašević’s class, Višnja Jelačić and Višnja Markovinović worked in ceramics and ceramic sculptures. After studying fine arts, Lidija Laforest experimented with photograms and photo collages, using ready-made photograms. These dealt with individual authorial personalities who were equally successfully involved in different ways of artistic expression: from sculpture and painting to graphic design as well as in the multidisciplinary fields of spatial design, objects for everyday use, applied arts, graphic design and animated film.

Besides the fine arts, the layered design of stage spaces is also crucial to an understanding of the poetics of space that builds specific visual expressions. This includes costume design and sculpture and the fact that the majority of AAA graduates active in animated media made connections between the ludic character of the media, seriality as a structural feature, a self-ironic sensibility, performativity and the theatricalisation of media. Experiment as a method, that is, collaborative work on finding steady and organised solutions to project tasks are recognisable features of their actions. Numerous AAA graduates worked in graphic design, especially in the then nascent sphere of advertising design. Jože Rebernak, collaborating with the advertising agencies Interpublic and Ozeha, and the Zagreb Fair created an exceptionally interesting and prolific body of work in the field of commercial graphic design. At the same time, despite the relatively adverse conditions in Yugoslav industry, many designers established themselves in the new design profession. Bruno Planinšek, Milan Dobrić, Vladimir Frgić, Boris Babić and Mario Antonini, who were graduates of the architectural department of the Zagreb Academy of Applied Arts, are all names who achieved important works through collaborating with industry immediately after completing their studies.

As fresh AAA graduates, they became involved in the public sphere and media space along with their (by then former) teachers. They became protagonists promoting design at exhibitions, and they endorsed the programme’s principles in their practice. The Milan Triennial was the model that inspired the Zagreb Triennial. At the Zagreb triennial’s initial Exhibition in 1955, protagonists of design (who were former AAA students) were present in all sections as exhibitors. The same year, they were among the founding members of the Industrial Design Studio (Studio za industrijsko oblikovanje, SIO), the first group founded in Yugoslavia that sought to work in an organised manner on industrial design problems. The manifesto, which was signed by the architects Bregovac and Richter and by three AAA graduates (Antonini, Babić and Frgić), clearly expresses their advocating a strategy for the ‘radical design of industrial buildings’ for mass production.

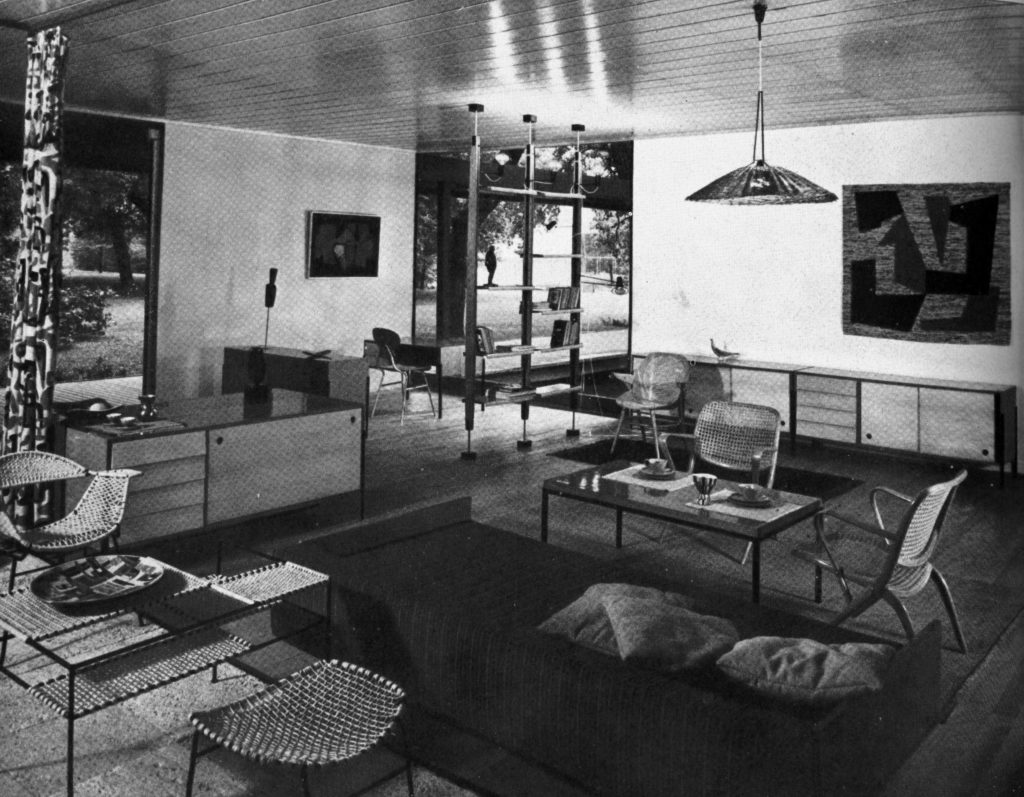

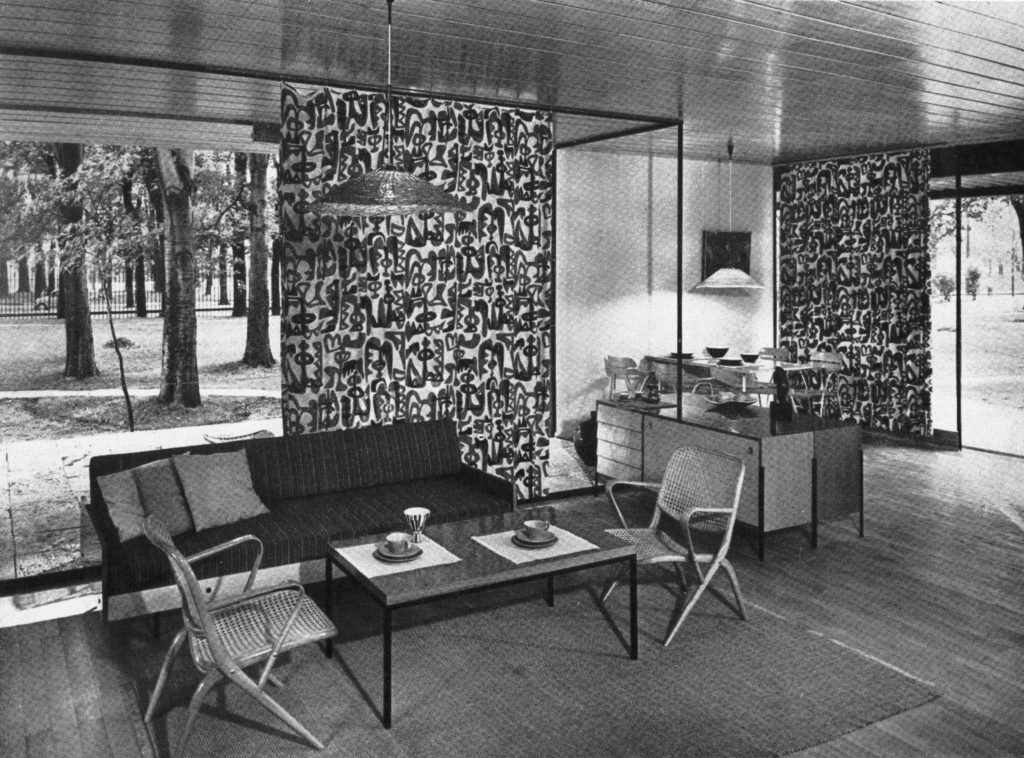

The SIO programme was first presented at the exhibition Stan za naše prilike/Housing under Current Conditions in Ljubljana in 1956. Three residential environments were showcased, which were equipped entirely with products from Yugoslav industry. SIO’s greatest achievement was their appearance at the 11th Milan Triennial (1957) where the Yugoslav residential environments featured alongside the French, German, Danish, Swedish, Finnish and Italian environments at this international exhibition on housing. The framework for the exhibition setup was designed by Mario Antonini and Boris Babić, and it was made of a system of modular furniture produced in the DIP Novoselec factory, created by the same designers. The other exhibits also played an important part in the environment’s structural unity, from art compositions, sculptures of decorative materials, ceramics and glass to lighting fixtures.

Most of the works by AAA graduates confirmed the ‘plastic synthesis’ principle in practice. One strand of AAA graduates and teachers presented what was for them the high point of the 1950s at the exhibition of the 2nd Zagreb Triennial in 1959, where the foundational principles of design as identified in the programme goals of the Academy of Applied Arts were conceptually implemented.

[9] Branka Frangeš Hegedušić (1906–1985) enrolled on the fine arts programme in 1924 at the Royal Academy of Arts and Crafts in Zagreb, together with Ivana Tomljenović. Otti Berger was already studying there at that time and would – like Ivana Tomljenović – continue her education at Bauhaus after finishing her studies at the Academy.

is an art historian and professor at the University of Zagreb. Before joining the University in 2001, she worked at the Museum of Arts and Crafts in Zagreb as a curator of the collection of design and architecture. Her research interests focus on history and theory of architecture, design history and cultural history as well as the relations of modernism and nationalism in art historical discourses of the 20th century. She has published on design, arts and crafts, architectural criticism, cultural history of modernist magazines, curated and co-curated several exhibitions, including “Reflections of Bauhaus: the Academy of Applied Arts in Zagreb, 1949–1955″ (2019). Her most recent book is “The Foreign Designer. Antoinette Krasnik and the Wiener Moderne” (2020).