Reception of the Bauhaus in Forming the New Socialist Daily Life

In early 1961, Slovenian director Jože Babić made the film Sudar na paralelama[1] that indirectly depicted the influences of the Bauhaus on the Croatian and especially Zagrebian culture of living. Using a contemporary socialist individual as an example, he interpreted these influences as the result of the activity of the group EXAT 51 and the Academy of Applied Arts in Zagreb.[2] Shot at several locations in Zagreb, the film shows the city’s urban life in contemporary, public, business and private environments in the early 1960s. It is an important source for studying the culture of everyday life in those days. It documented the prefabricated building of the first self-service fashion department store, built in 1960 in the city centre, inside and outside, a residential building outside of the city centre built under the strong influence of Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation,[3] and a modern, functionally furnished flat of a young, fashionable married couple. Coincidentally, the film was produced in 1961, the same year that saw the First Summit of the Non-Aligned Movement in Belgrade, at which Yugoslavia assumed a leading position on the political map of Europe and the world in establishing relations between the non-aligned countries and the two geopolitical blocs. All of this makes the film a document of the new cultural and political climate marked by a tacit influence of the West on the new socialist society.

The film’s camera recorded the contemporary scenery of Zagreb, the capital of Croatia that was at the time one of the six republics constituting Yugoslavia, a country whose social system was based on Marxist theories. After the Second World War, Yugoslavia was politically bound to the Soviet Union; already in 1948, however, a break in the complex relations ensued, new connections with western countries were established, and Yugoslavia gained an important geopolitical position between the east and the west. Still, Yugoslavia did not renounce Communist ideology, but rather developed – as an eccentric member of the family of socialist countries – a hybrid socio-political model in which the society absorbed western influences just as much as was possible or, more precisely, just as much as was allowed by the authorities. We can therefore conclude that this was the most democratic country of the Eastern Bloc and, simultaneously, the least democratic country of the west.[4] Once the relations with the Soviet Union had been terminated, the current of socialist realism quickly lost its dominant role, which paved the way for the development of abstract art that would go on to be used more and more often in promoting the state at international level. Following the Second World War, the development of abstract art was related to the activity of Zagrebian artists, architects and designers, founders of the group EXAT 51, who unequivocally stated in their 1951 manifesto their attitudes based on experimentation, abstract art and, finally, their aim to achieve synthesis between fine art, architecture and design.[5] It is necessary to point out, however, that the emergence of the group EXAT 51 is bound to the heritage of avant-garde movements in Zagreb in the 1920s, which were rooted in the city’s belonging to the Central European cultural circle, which in turn created the best foundation for the further development of abstract art compared to other urban environments in Yugoslavia.

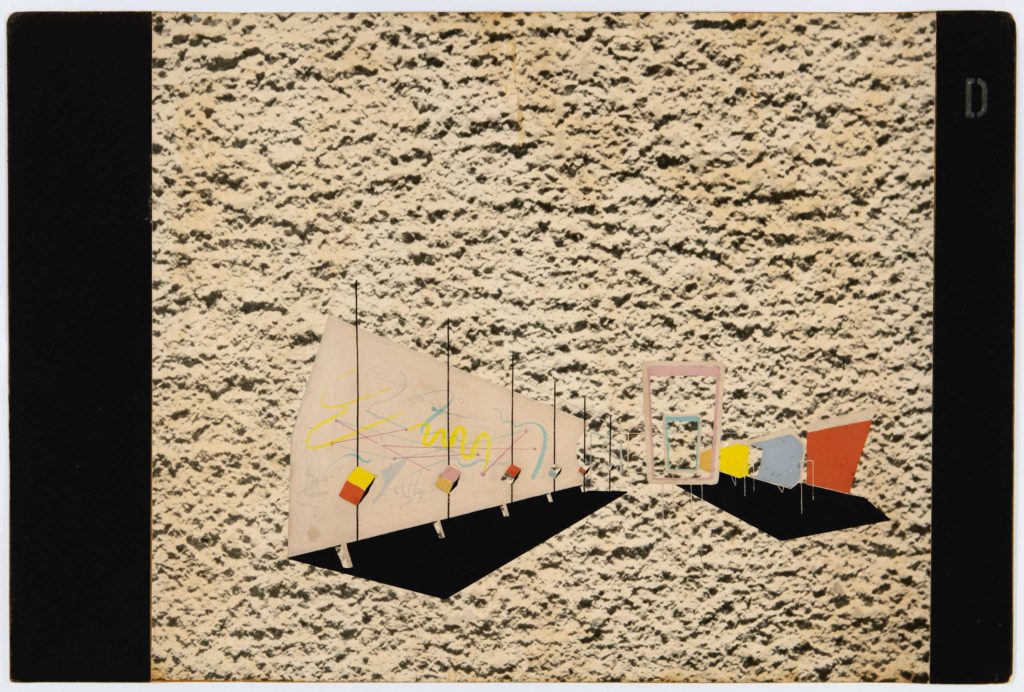

1949 and 1950, several exhibition pavilions were created with which Yugoslavia was represented at international fairs, designed by the then young authors and future members of the group EXAT 51, architect Vjenceslav Richter and artists Ivan Picelj and Aleksandar Srnec. In these projects, the authors would go on to achieve the very freedom of creation that they emphasised later on in the group’s manifesto, which rests on the interdisciplinary approach and aesthetics of the Bauhaus. In this new synthetic way of working, a dynamic relationship was developed between exhibition architecture and the exhibited object, i.e., the “spatial concept” as defined by Richter.

[1] Film was distributed in Germany under the title Dienstreise im Schlafwagen.

[2] I would like to extend my gratitude to Andrea Klobučar, Senior Curator at the Museum of Arts and Crafts, for her selfless help and especially for pointing out to me the importance of this film.

[3] The residential building on 35-35a Vukovar Avenue was built in 1953 according to the project by architect Drago Galić.

[4] Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Extremes: A History of the World, 1914–1991, New York: Pantheon Books, 1994; Midhat Ajanović, Animation and Realism, Zagreb: Croatian Film Association, 2004.

[5] The group EXAT 51 (Experimental Atelier 51) was founded in Zagreb in 1951. Its members were Bernardo Bernardi, Zdravko Bregovac, Zvonimir Radić, Božidar Rašica, Vjenceslav Richter, Vladimir Zarahović, Aleksandar Srnec, Ivan Picelj, Vladimir Kristl. The Group officially operated until 1956.

Under the new political circumstances, the idiom of abstraction was used in a very specific manner. Hence, when we speak of artistic freedom, the authors had a more or less flexible creative boundary that left them room to manoeuvre. This situation also favoured the founding of the Academy of Applied Arts in 1949.[6] The Academy’s curriculum was modelled on the Bauhaus, centred on the preliminary course followed by specialist studies in architecture, sculpture, printmaking, textile, ceramics, and painting. The Academy’s educational programme aimed at creating a cadre who would apply aesthetic and fine art criteria in the design of industrially produced objects.

The Academy of Applied Arts in Zagreb would go on to have far-reaching effects that can be observed in the works of a generation of students, but also in the broader sense, i.e., in architectural and artistic creations of authors close to the Academy, but from different educational paths on which they adopted the legacy of historical avant-gardes, the progressive pedagogy of the Bauhaus, which led them towards experimenting and searching for authentic spatial and artistic manifestations. The artists and architects of Zagreb were familiar with the events in Europe through private contacts, journals and specialist literature that regularly covered the then recent international practices and accomplishments in the field of architecture, art and design. The curriculum of the Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm (HfG, Ulm School of Design) and the construction drawings for its building were well-known to the artist Ivan Picelj, who was in frequent contact with Max Bill, co-founder of the HfG. A draft of the HfG’s educational programme suggests that, at the time when the Academy of Applied Arts had already existed in Zagreb, these two artists probably discussed the educational model of the HfG.[7]

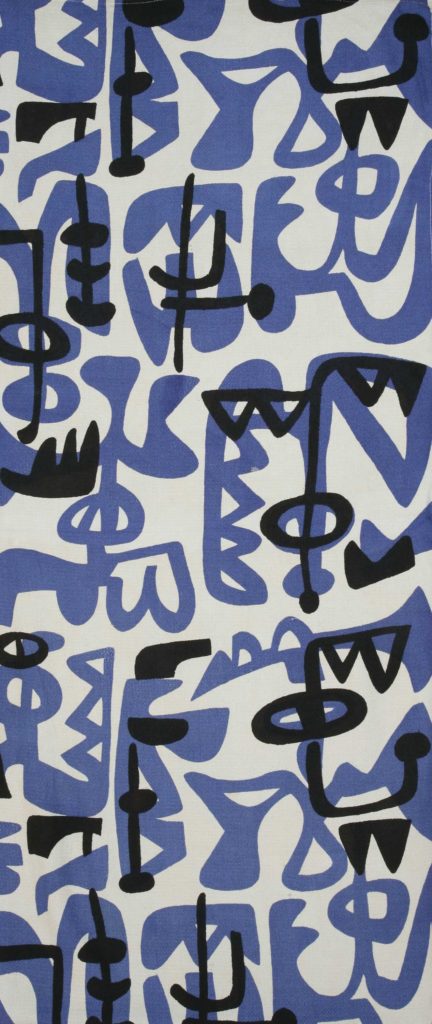

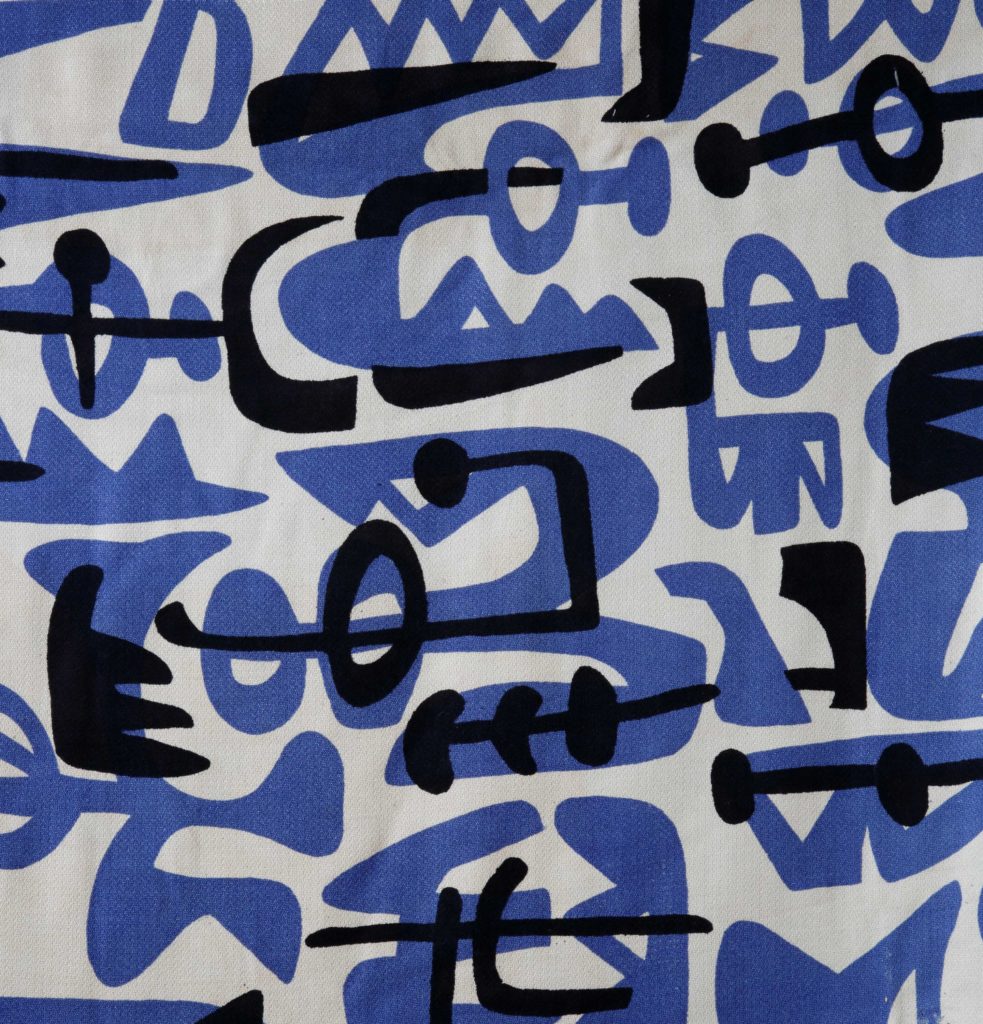

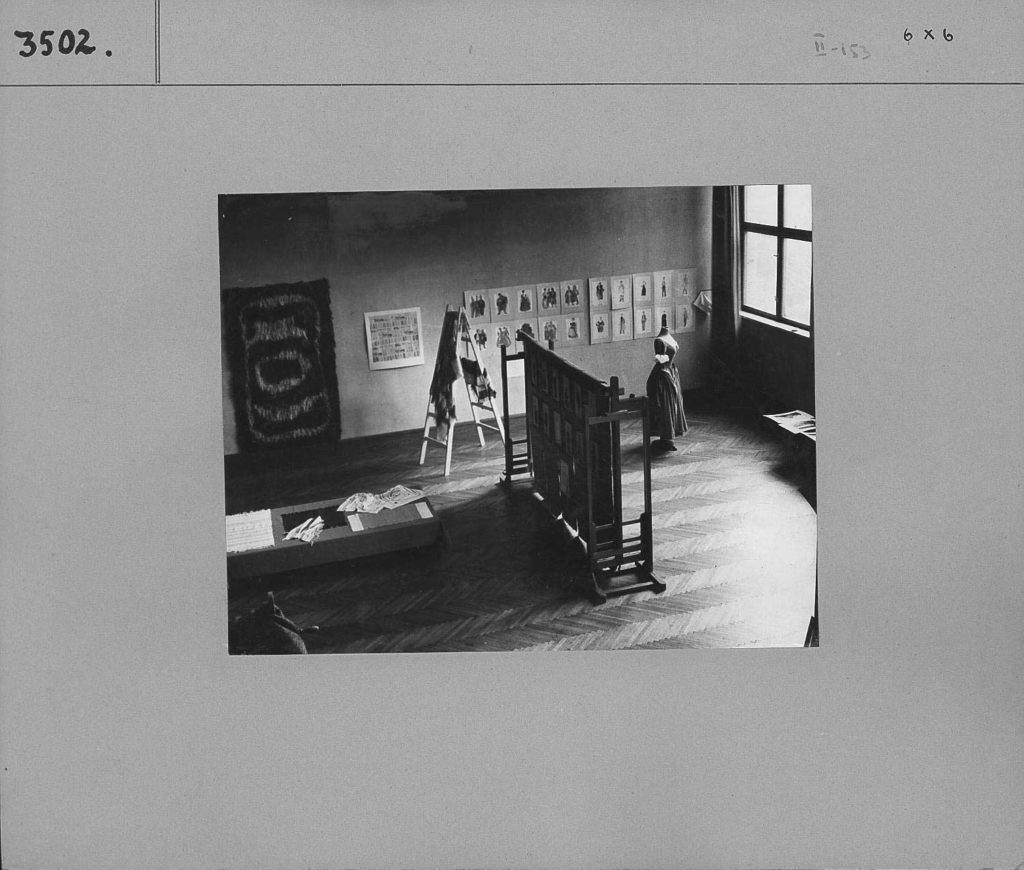

Zdenka Munk, then Director of the Museum of Arts and Crafts in Zagreb, was highly aware of the importance and significance of the Academy of Applied Arts. After the Academy had closed in 1955, she selected some of the students’ works and stored them in the Museum’s holdings. Hence, the works of the former students at the Academy – who achieved exceptional careers in different artistic fields and applied in their creation the principles of experimentation, research and interdisciplinarity – have been preserved. Around 100 works, mostly dated between 1953 and 1955, are part of the collections of the Museum of Arts and Crafts. The works by students of the textile department are among those that stand out the most: carpet sketches by Zlata Komadina Krmpotić, Jasna Novak Šubić and Marina Gerasimenko-Kalentić, templates for a carpet, decorative fabric and a spatial sketch by Jagoda Buić, decorative fabric templates by Vlasta Hegedušić, Jasna Stahuljak, Zora Petrović Mohorovičić and Nada Kunaj Landski.

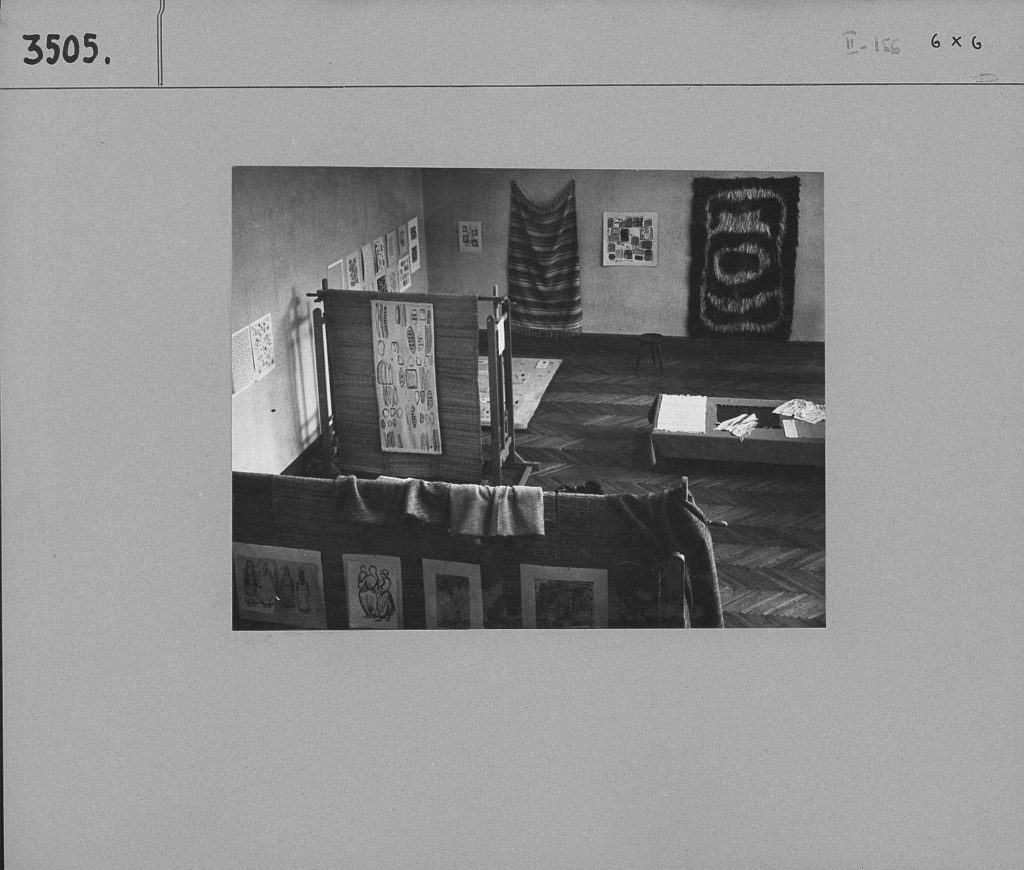

The pedagogical programme of the Academy’s textile department was conceived by artist Branka Hegedušić, and it aimed at the design and production of prototypes of fabrics, carpets, patterns for printed textiles and apparel models. The programme encompassed theoretical and practical classes in workshops, while the Bauhaus principle was also evident in the exhibitions of students’ works. The exhibition of the Academy’s textile department, held in 1955 at the Master Workshop of Krsto Hegedušić,[8] evoked memories of Bauhaus exhibitions from the school’s time in Weimar. Alongside textile works, it is also worth noting the student works by Vasko Lipovac and Ordan Petlevski within the framework of the painting department, and Zlatko Bourek as one of the students of the sculpture department, who tirelessly created in different media throughout his long career, from the traditional areas of painting and sculpture to set design, costume design and animation. The works by students of the printmaking and ceramics departments remain a subject for future research, as well as the oeuvres of students of the architecture department, whose creations remain insufficiently known for the time being.[9]

[6] The Academy of Applied Arts in Zagreb operated between 1949 and 1955 and saw a single generation of graduates.

[7] The draft of the educational programme for the Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm is kept at the Archives and Library of Ivan Picelj, Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb, IP-EX-D53-10.

[8] Andrea Klobučar, ‘The Textile Department of the Crafts School and Academy of Applied Arts in Zagreb – an Example of the Bauhaus Educational Mode’, in: Jadranka Vinterhalter (ed.). Bauhaus – Networking Ideas and Practice, exhibition catalogue. Zagreb: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2015.

[9] For more information on authorial ceramics of the late 1950s and the 1960s, see Marina Bagarić. ‘The Golden Age of Ceramic Artists’, in: Vesna Ledić, Adriana Prlić, Miroslava Vučić (eds.). The Sixties in Croatia – Myth and Reality. Zagreb: Museum of Arts and Crafts and Školska knjiga, 2018.

The influence of aesthetics and design of the Academy of Applied Arts is visible in the design of interior spaces which serve as settings for the film Sudar na paralelama. Most of the plot occurs in a modernly furnished, relatively small flat which is arranged according to a model flat designed by Bernardo Bernardi, a member of the group EXAT 51, at a call for proposals entitled ‘Housing for the near future’ launched in 1960 within the framework of the 3rd Family and Household exhibition held in Zagreb. This flat conveys in a certain way Bernardi’s idea of the living space as a potential site of synthesis. The space is equipped with functional minimalist furniture and neatly decorated with different utility objects with simple geometrical lines and décor. The film’s main characters, a young married couple dressed according to the latest fashion of the time, discuss the contemporary topic of emancipation, prompted by a business offer that is supposed to enable the advancement of the young woman’s career.

The film’s opening scenes were shot in and outside of the department store, where the main protagonists are talking while looking at clothing items. This department store was built according to a project by Aleksandar Dragomanović and Ninoslav Kućan from 1958; it is a prefabricated edifice made of glass and metal, initially erected at the 2nd Family and Household exhibition as an example of a standardised department store. In April 1960, this edifice was erected in the historic core of the Zagreb city centre, at the site of the former synagogue.[10] The film scenes also reveal details of the department store’s minimalistic interior with mannequins created by Ante Jakić, an artist who received his education at the sculpture department of the Academy of Applied Arts in Zagreb. Several years later, in 1966, Jakić made the wooden toys TO TAK, composed of free elements in the form of bells, pebbles, truncated cones and spheres, out of which different animals could be assembled.[11] The film presented to a wider audience in an indirect manner the model of the contemporary way of life – from interior design and fashion to the new role of women in society.

The citizens of Zagreb adopted these new tendencies in everyday life by dwelling in modern houses and moving around public places designed by young architects and designers who were closely linked to the ideas and legacy of the Bauhaus. Expert literature of the period regularly published and covered the achievements in the field of global and national architecture and art. The department store as a standardised edifice was therefore published in the major journal of architecture Čovjek i proctor. The journal’s editor-in-chief was Vjenceslav Richter, one of the leading architects, theoreticians and artists of the second half of the 20th century, member of the group EXAT 51, a “part-time lecturer” at the Academy of Applied Arts where he taught construction and planning at the architecture department. His colleagues and close associates, such as Zvonimir Radić and Đuka Kavurić, also taught at the Academy or were students, among them Aleksandar Srnec.

Vjenceslav Richter designed the Yugoslav Pavilion at the World’s Fair in Brussels in 1958. Just like the department store in the Zagreb city centre, it was made of glass and metal and was created under the strong influence of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s architecture. In a broader sense, this was functional architecture that could be adapted to different purposes. It is exactly what Richter’s pavilion demonstrated when it was dismantled following the end of the World’s Fair in Brussels and moved to a new location, to the Belgian town of Wevelgem, where it was successfully reconstructed for a new purpose – a school. As such, it is still being used today.

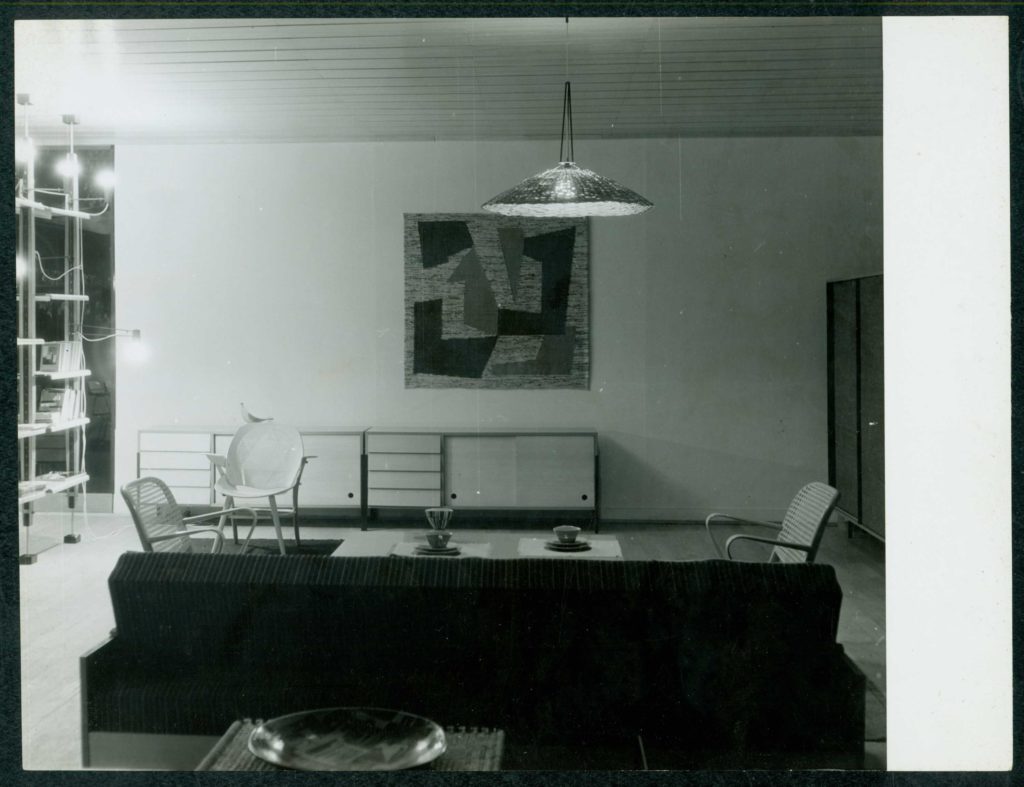

One of the most noted and complex implementations, which showed the potential of collective action and experimentation in the extended fields of art, design and architecture, was the presentation of a group of architects, painters, sculptors and textile designers at the 11th Triennial in Milan in 1957. On that occasion, Yugoslavia presented a contemporarily designed residential space that was awarded the prestigious Silver Medal. The design’s main principle of plastic synthesis was applied by designers not limiting themselves to a single discipline. Mario Antonini and Boris Babić, according to whose plans the furniture was produced, were responsible of the setup, while the colour scheme was designed by Ivan Picelj. The interdisciplinary collaboration is most clearly evident in the garden furniture set made from wrought iron and corn husk, produced by textile designer Slava Antoljak and designer Ferdo Rosić according to the project by architect Vjenceslav Richter.

The interior of the residential space was completed with different objects with which an integral and harmonious living space was fully formed, among them a tapestry produced by Slava Antoljak according to a template by Ivan Picelj, paintings by Aleksandar Srnec and Božidar Rašica, sculptures by Vojin Bakić, Zlatko Bourek and Kosta Angeli Radovani, utility and decorative ceramics authored by Marta Šribar, Vlasta Baranyai, Ljerka Šarić-Joan, Stela Skopal, Mila Petričić and Milan Kičin, a chair by Niko Kralj, and the entire space was completed with decorative fabrics by Jagoda Buić Bonetti and a light fixture designed by Vjenceslav Richter.[12]

The presentation at the 11th Triennial in Milan was preceded by the founding of the Studio za industrijsko oblikovanje (Studio for Industrial Design, SIO) at the Association of Fine and Applied Arts in Croatia in 1956. SIO’s role as a professional association was to promote the idea of industrial design whereby Bernardo Bernardi played a crucial role. The Silver Medal from the 11th Triennial in Milan was one of the greatest recognitions for Yugoslav design of the time, while the award-winning interior is also one of the rare collective creations with a starting point in the creative principles of the Bauhaus.

[10] Alen Žunić, Zlatko Karač, ‘Department Stores and Shopping Centers Designed by the Architect Aleksandar Dragomanović’, Prostor 23, 2015, p. 277–303. The department store no longer exists. It burned down in 1980.

[11] Koraljka Vlajo. ‘The Golden Age of Croatian Design’, in: Vesna Ledić, Adriana Prlić, Miroslava Vučić (eds.). The Sixties in Croatia – Myth and Reality, Zagreb: Museum of Arts and Crafts and Školska knjiga, 2018.

[12] Jasna Galjer, Design of the Fifties in Croatia: From Utopia to Reality, Zagreb: Horetzky, 2004.

The influences of design principles of the Bauhaus’s pedagogical model, assimilated in the Croatian cultural environment through the activity of the group EXAT 51 and the Academy of Applied Arts, reached their peak in the presentation at the 11th Triennial in Milan in 1957. In that light, the Milan Triennial was a breakpoint after which such a successful form of collaboration was never achieved again. Most of the designers who kept up the principles of experimentation and research produced significant individual oeuvres, as testified by the personal narratives of authors such as Vjenceslav Richter,[13] Jagoda Buić,[14] Bernardo Bernardi,[15] Zlatko Bourek,[16] Ivan Picelj,[17] Ordan Petlevski,[18] Ante Jakić, Aleksandar Srnec, and other protagonists of the Croatian cultural scene, whose oeuvres are awaiting more in-depth research.

[13] Vesna Meštrić, Martina Munivrana (eds.) Vjenceslav Richter – Rebel with a Vision, Zagreb: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2017.

[14] Anđelka Galić (ed.). Jagoda Buić – Retrospektiva/Retrospective, Zagreb: Museum of Arts and Crafts, 2010.

[15] Iva Ceraj. Bernardo Bernardi: The Design Work of an Architect 1951–1985, Zagreb: Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts, 2015.

[16] Tonko Maroević. Zlatko Bourek. Zagreb: Modern Gallery, 2014.

[17] Biserka Rauter-Plančić (ed). Ivan Picelj: Kristal & ploha: 1951–2005. Zagreb: Gallery Klovićevi dvori, 2005.

[18] Grgo Gamulin. Ordan Petlevski. Zagreb: Nakladni zavod Matice hrvatske, 1990.

(b. 1972) is an art historian and senior curator in the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb, and as such she is in charge of two collections: the Richter Collection and the Marie-Luise Betlheim Collection. She is co-author of the research and exhibition project Bauhaus – Networking Ideas and Practice, and has curated various solo and topical exhibitions. Her research interests include interpretation and presentation of collections, focusing on avant-garde and postmodern movements.