Mart Stam in Dresden

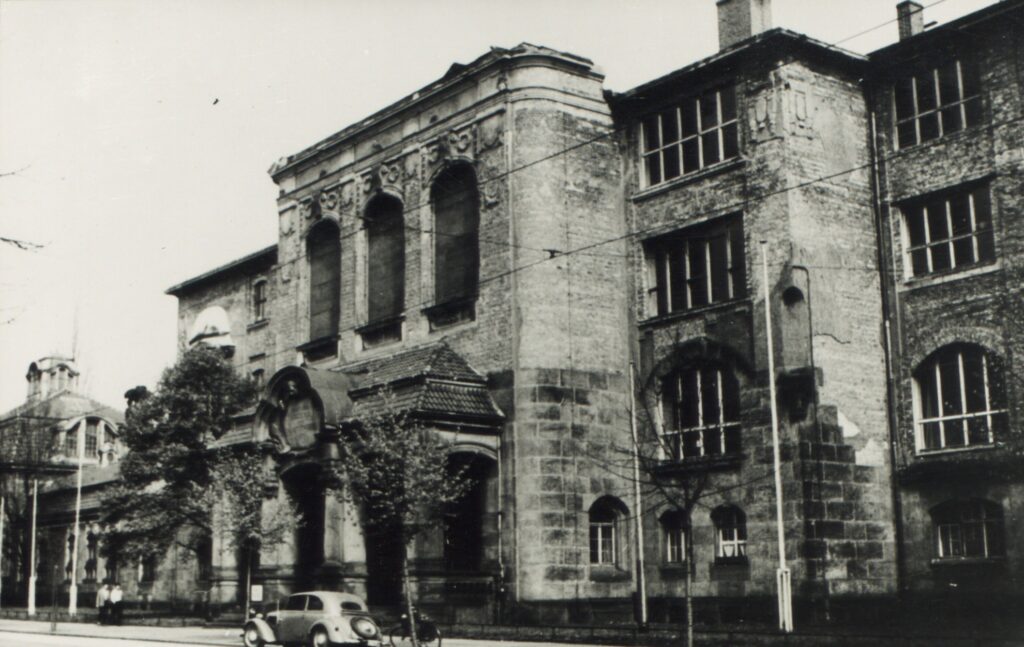

Founded in 1764 as the Allgemeine Kunst-Akademie der Malerei, Bildhauer-Kunst, Kupferstecher- und Baukunst (general art academy of painting, sculpture, copperplate-engraving and architecture), the Königliche Kunstakademie (royal academy of arts) is one of the oldest art academies in Germany. In 1875/76, the Königlich Sächsische Kunstgewerbeschule (royal Saxon school of applied art) was also founded. After the First World War, this became the Staatliche Akademie für Kunstgewerbe (state academy of applied art). In 1931, a merger of the two academies was proposed, but faltered due to objections raised by the art academy. The proposition was first revived post-1945 and implemented in 1950.

In Weißwasser, a town 80 kilometres from Dresden, German electrical companies were modernising glass manufacture at their Vereinigte Lausitzer Glaswerken AG. In 1935, the Bauhausler Wilhelm Wagenfeld took up the position of the firm’s artistic director.

In Dresden, where the destroyed city was being rebuilt after the war and the two academies were being reorganised, Wagenfeld saw the opportunity for a project with the potential to transcend corporate particular interests. In July 1945, he received a letter from Dresden city council offering him an opportunity to ‘establish a workshop for industrial product design’ in an ‘academy of arts and crafts based on entirely new foundations’.[1]

In June 1946, Wagenfeld wrote a letter to the Amt für Betriebsneuordnung, the authority in charge of expropriating businesses, which was led by Otto Falkenberg. Like his supervisor Fritz Selbmann, Falkenberg ranked among the politicians who set about transforming Saxony’s economy into a state-run planned economy. In this letter, Wagenfeld outlined of a “reorganisation of the glass industry”, which ought to be of economic and cultural significance.[2] In a nationwide amalgamation of glass factories, ‘production in all factories and works under the control of the Amt für Betriebsneuordnung should be limited to a few essential product types of specified design and quality’.[3]

A final attempt to bring Wagenfeld to Dresden was undertaken by Will Grohmann, whom Selbmann had appointed as principal in order to unite the academy of art with the academy of applied art. His plan would see Wagenfeld head an industrial design department at the renowned company Deutsche Werkstätten in Hellerau, a district of Dresden.[4] During a talk at the Hochschule für Werkkunst (academy of applied art), Wagenfeld spoke of a cooperation between artists, technicians and craftsmen, from which would emerge ‘something completely anonymous’.[5] But Grohmann’s time was up; he resigned in early 1948.[6] Wagenfeld moved to Berlin in 1946 and was made a professor of industrial design at the University of Arts before relocating to Stuttgart in 1949. This paved the way for Mart Stam’s arrival on the scene in Dresden.

[1] Culture office of the Dresden City Council, State Administration of Saxony, Ministry of Internal Affairs, to Wilhelm Wagenfeld, 20 July 1945, former private archive of Erika Wagenfeld.

[2] Wilhelm Wagenfeld to Mr Andörfer, Amt für Betriebsneuordnung (the authority in charge of expropriating businesses), Dresden, 29 July 1946, former private archive Erika Wagenfeld.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Minutes of a meeting of the Hochschule für Werkkunst (academy of applied art), 6 February 1946, HfBK Dresden Archive, 0301/1352.

[5] Minutes of a meeting of the Hochschule für Werkkunst (academy of applied art), 7 May 1946, HfBK Dresden Archive, 0301/1352.

[6] Hochschule für Werkkunst (academy of applied art), faculty meeting minutes of 15 January 1948, HfBK Dresden Archive, 0301/1352.

The Federal Republic of Germany was founded in May 1949, the German Democratic Republic in October the same year. The decision for opposing societal systems had now been made and soon came to have an impact on the fine and applied arts in Dresden too.

Mart Stam in Dresden: That this major avant-gardist of European modernism chose Dresden in 1948 is of note especially in comparison with similar developments underway in Weimar and Berlin. In the late-1940s, Stam could hope that the new socialist republic might again turn towards modernism. Liv Falkenberg, whom Mart Stam knew well from earlier days in Rotterdam, noted how this came about. Her husband, Otto Falkenberg, had written to her, saying that there was a great deal of rebuilding to do in Dresden. This would be something for Stam, who had learned in Russia to consider and plan for everything required so that a place might function.[7]

On 1 July 1948, Stam was invited to Dresden and on 15 December that year, he was appointed director of both state-run academies.[8] Stam immediately began to organise sufficient repairs to the war-damaged building so that teaching might again take place on a regular basis.[9] Now, he could think about a radical new start. In October, he contemplated a ‘new art school – a state academy for contemporary design’, but by November, his proposal to the Ministry of National Education in Saxony described an ‘Academy of Architecture – a state academy for free and industrial design’.[10] This highlights Stam’s programmatic affinity with the Bauhaus.

[7] Klaus Kühnel. Der Mensch ist ein sehr seltsames Möbelstück. Biographie der Innenarchitektin Liv Falkenberg-Liefrinck, geb. 1901/erfragt und aufgeschrieben von Klaus Kühnel. Berlin: trafo, 2006, p. 117.

[8] Stam personal files, HfBK Dresden Archive.

[9] Cf. ‘Archivale des Monats August 2017’ (document of the month of August 2017), Mart Stam personal file, HfBK Dresden Archive.

[10] Wolfgang Rother, ‚Mart Stam in Dresden‘, in: Beck, Rainer and Kardinar, Natalia (Eds.), Trotzdem. Neuanfang 1947. Zur Widereröffnung der Akademie der Bildenden Künste Dresden. Dresden: Verlag der Kunst, 1997, p. 156.

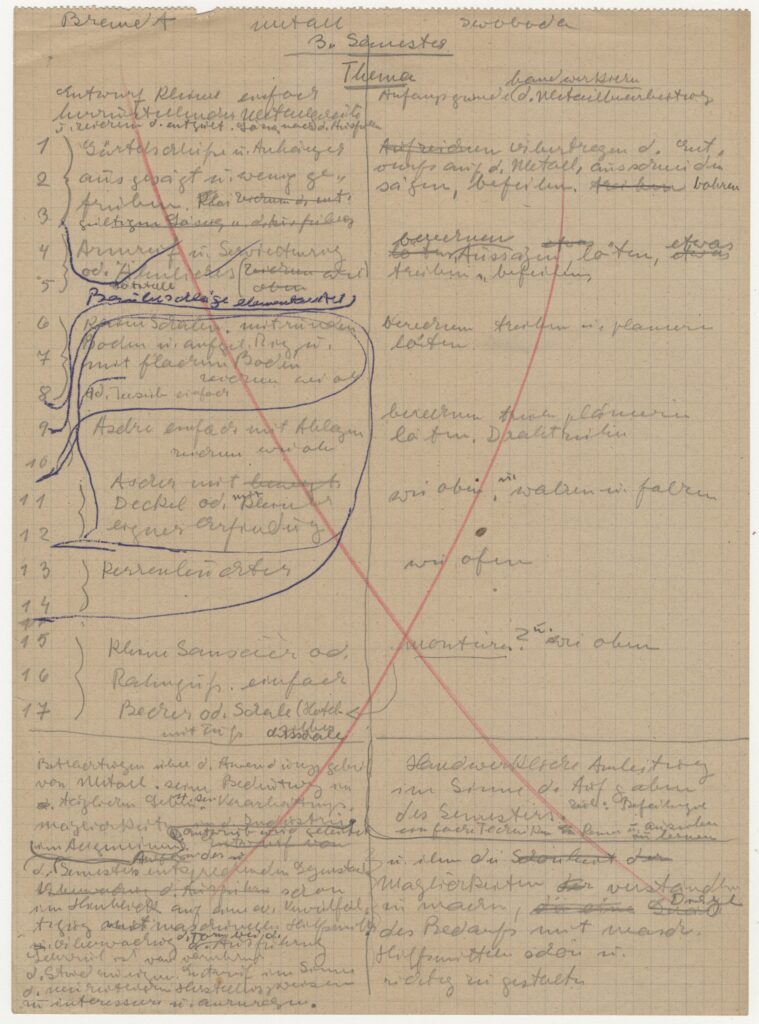

In March 1949, Stam informed the state government of Saxony about his inaugural speech to mark the merger of the two academies. In it, he emphasised the formation of a ‘faculty of industrial design’: ‘As you will surely understand, I consider this faculty to be a vitally important one, especially in this day and age and in our part of Germany, in which attempts are being made to build up and develop in every area the manufacture of commodities. This faculty should train the industrial designer for industrialism in every sector.’ He singles out the ceramics, glass, metal, furniture, automobile and sewing machine industries and even the machine industry.[11]

[11] Mart Stam, inaugural address, no date, p. 22f, Ministry of National Education, no. 1658, Hauptstaatsarchiv Dresden.

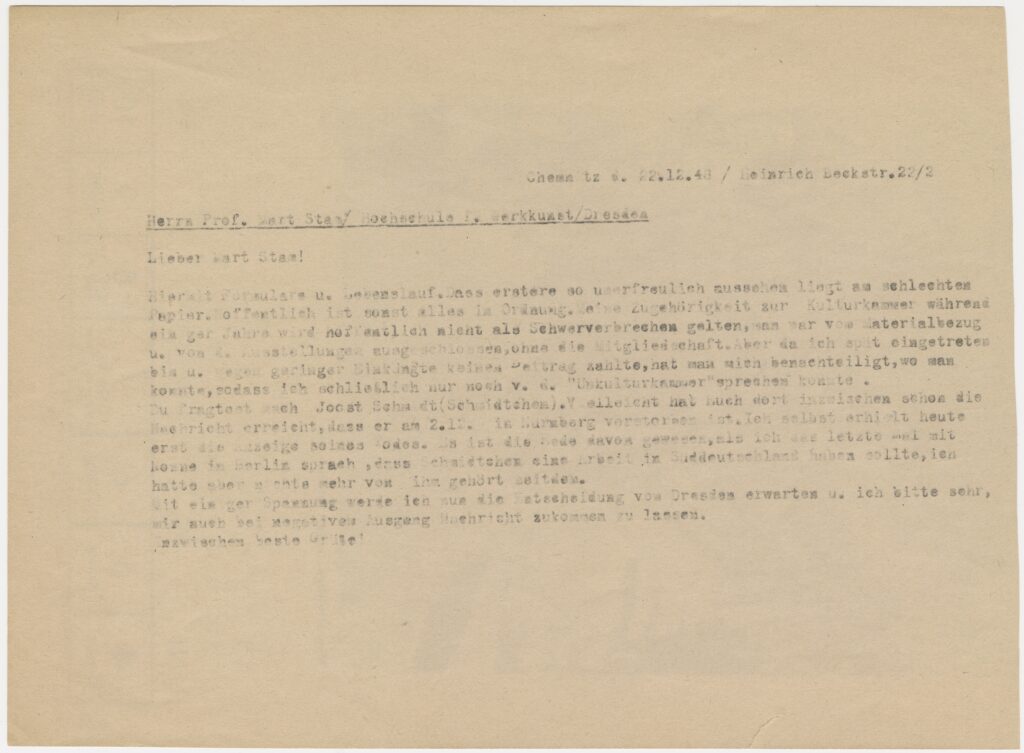

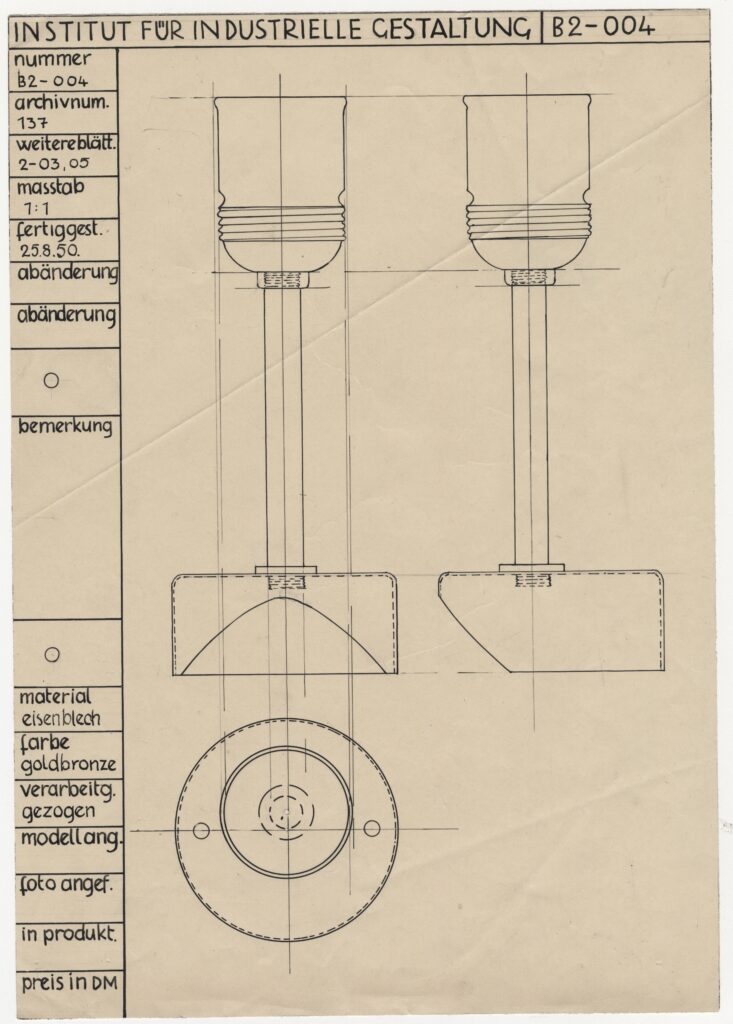

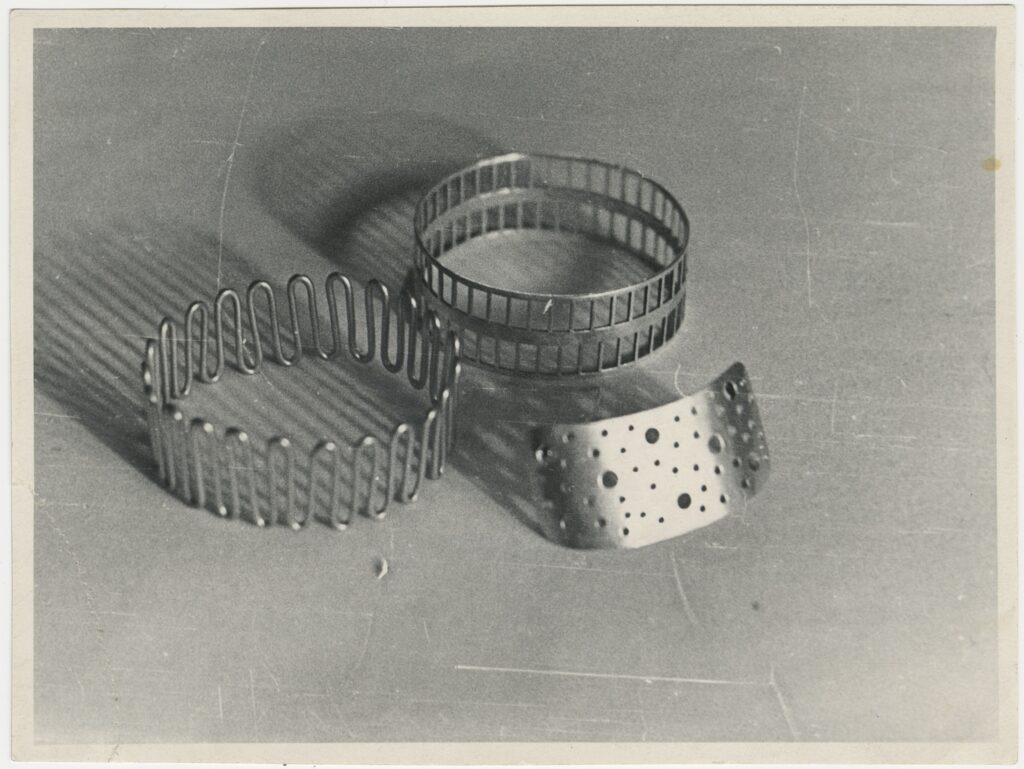

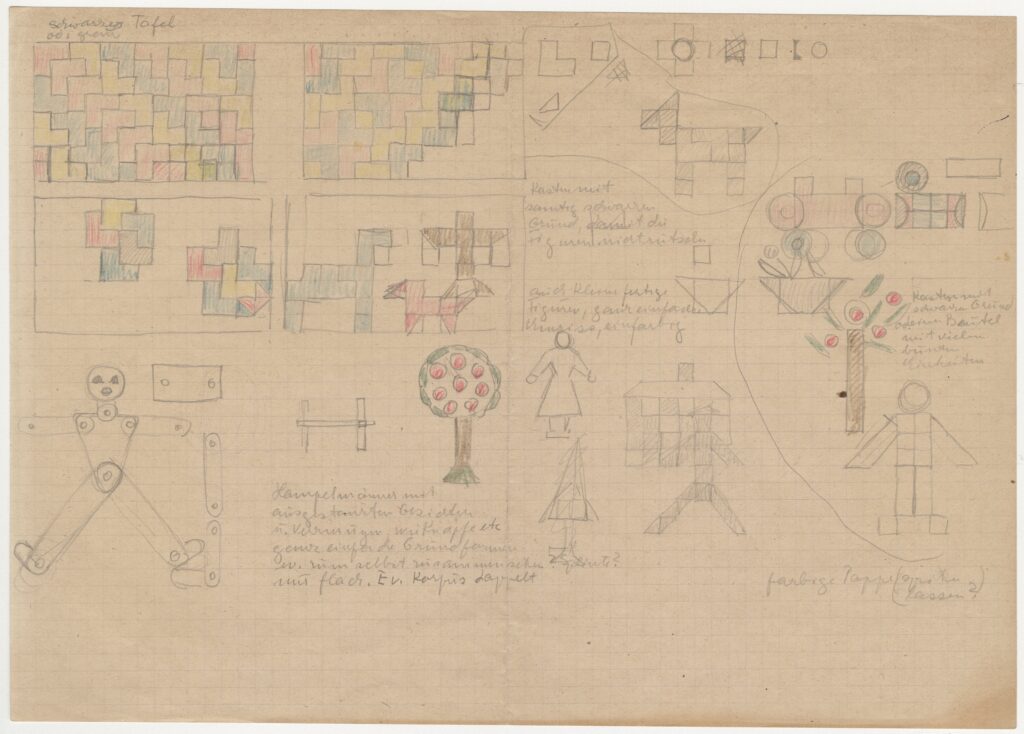

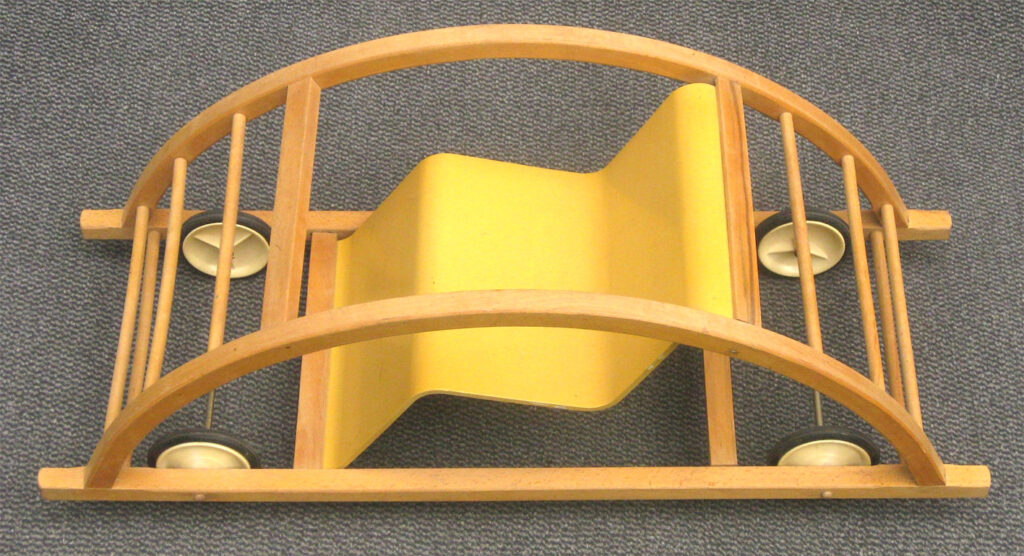

Stam set about reforming teaching at the academy with a series of appointments. One of the invitations was sent out to Marianne Brandt in Chemnitz. The Bauhaus student had had a very positive impact on the design of industrial products. Stam wrote to her in February 1929, saying that the new department would have a lot to do: Lighting fixtures made from ceramics, metal and wood, wooden toys as well as stoneware, porcelain and glass tableware.[12] Stam was able to appoint Hajo Rose to teach colour and form theory and lettering.[13]

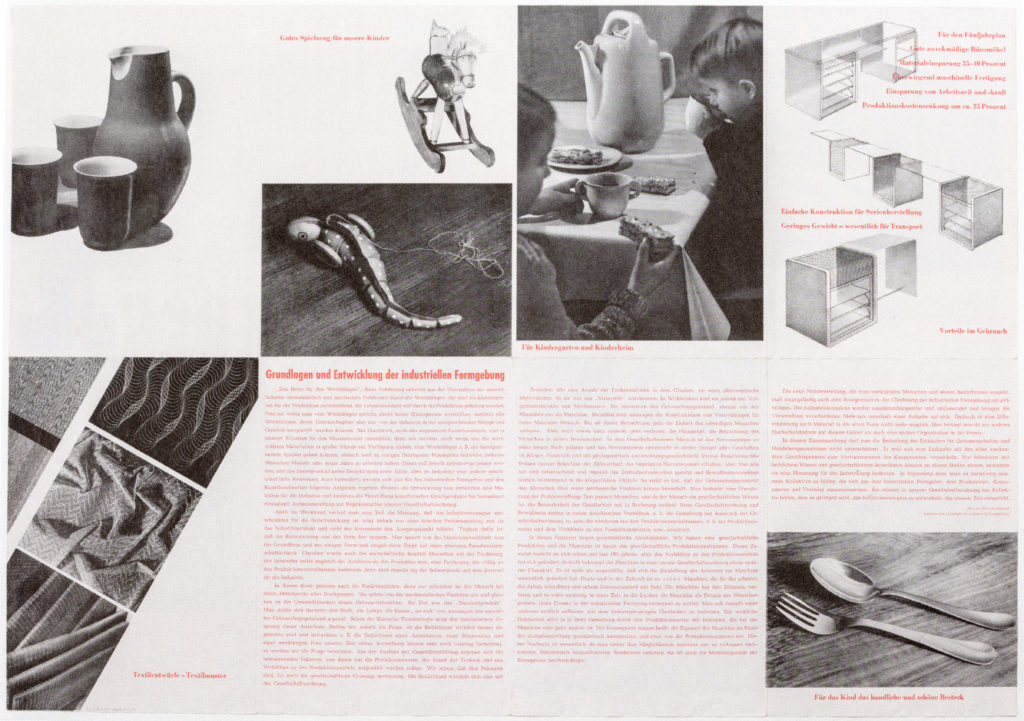

Together with the students, Stam, Brandt and Rose came up with practical and material-orientated designs for furniture, appliances and vessels, as illustrated in the leaflet produced by the academy in 1951, Das Beste für den Werktätigen (The best for the worker). A new generation of designers, among them Margarete Jahny and Hans Brockhage, followed in their wake. Mart Stam himself focused all his attention on new plans which, first as a two-year plan, then as a five-year plan, would dictate the designers’ work from political and economic perspectives. But in Dresden, the situation developed very differently from what he had expected.

[12] Mart Stam to Marianne Brandt, 7 February 1949, HfBK Dresden Archive, 01-218.

[13] Mart Stam to the Ministry of National Education, 27 November 1948, HfBK Dresden Archive, 01-218.

Stam failed with his plan to rebuild the ruins of Dresden and with his model for a palace of culture in Böhlen. And although he had been appointed head of both to-be-merged academies, their incorporation as the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts first came about following his departure in June 1950.

While Stam could rely on support from cultural policymakers like Otto Falkenberg, Fritz Selbmann and Gerhard Strauss of the Deutsche Verwaltung für Volksbildung (German authority for national education), artists acting against Stam like Hans and Lea Grundig had the attention of Helmut Holtzhauer at the Ministry of National Education. Hans Grundig insisted on the academy’s opposition to ‘the younger generation of artists educated according to the formal-abstract ideas and teaching methods of the Bauhaus in Weimar or Dessau’.[14] He sought a return to the distinction between the main forms of art. While Olga Stam, who had moved to Dresden with her husband as his collaborator, was turned down for a permanent post at the academies, Lea Grundig was appointed as vice rector to ensure the autonomy of the fine arts. Here, Holtzhauer had reached a decision that was scarcely tolerable for Mart Stam.

Grundig made a clear call for two faculties: fine art and industrial design. ‘Each of these faculties must be autonomous and within these, the individual departments of the fine arts must be built up according to their significance.’[15] Dresden’s reputation as a city of the arts was thus to be assured.

[14] Hans Grundig to Helmut Holtzhauer, Volksbildungsministerium Landesregierung Sachsen, 25 March 1949, Hauptstaatsarchiv Dresden, 11401-1631.

[15] Gerhard Strauss. ‘Mart Stam und sein früher Versuch, Traditionen des Bauhauses in der DDR schöpferisch aufzunehmen‘, Wissenschaftliche Zeitschrift der Hochschule für Architektur und Bauwesen Weimar, 50 Jahre Bauhaus Dessau, 23 (1976), issue 5/6, p. 540–542.Cf.

The 50th anniversary of the opening of the Bauhaus Dessau was celebrated in December 1976. At the accompanying colloquium, this modern heritage was finally officially acknowledged. The search for a fundamentally new understanding of Bauhaus modernism began.

On this occasion, the art historian Gerhard Strauss reminisced about Mart Stam and his early attempt to ‘creatively take up the traditions of the Bauhaus in the GDR’.[16] For Strauss, Stam’s concept for a Gesamtkunsthochschule, a ‘total’ school of art, was the clearest proof of a return to Bauhaus ideas. That this posited the primacy of architecture gave rise, Strauss thinks, to the aforementioned opposition among fine artists. As a result, it was proposed that, should he agree, Mart Stam would transfer to the architectural school in Weimar.[17] However, it was not Weimar, but the Weißensee Academy of Art Berlin that became Mart Stam’s new sphere until 1952. Strauss did not hesitate to draw a direct line from Weimar and Dessau to Berlin-Weißensee: ‘Thanks to Mart Stam’s concept, the Weißensee academy in Berlin is still to all intents and purposes the true heir of the Bauhaus in the GDR.’[18]

When Strauss evoked memories of the great avant-gardist’s early accomplishments in the GDR with this speech, Stam was still alive, living in Switzerland. He died in Goldach almost ten years later on 23 February 1986. But what of the two academies in Dresden? In 1950, they were merged to form the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts. The faculty of industrial design no longer exists. [19]

[16] Ibd.

[17] Ibid., p. 541.

[18] Ibid. Strauss added in his lecture that ‘out of a sense of obligation to a friend’, he planned to further explore Mart Stam’s oeuvre and dedicate a publication to him.

[19] This manuscript is abridged by the author Walter Scheiffele from his original essay entitled “Mart Stam in Dresden” in the publication: Die frühen Jahre. Mart Stam, das Institut und die Sammlung industrielle Gestaltung. Edited by Cornelia Hentschel, Walter Scheiffele, Jens Semrau for the Stiftung Industrie und Alltagskultur, Berlin: Lukasverlag, 2020, p. 44 et seqq.

Walter Scheiffele is a culture and design historian whose research interests include the Bauhaus and industrial design. His teaching posts at the Burg Giebichenstein University of Art and Design Halle and his visiting professorships at the Berlin University of the Arts and the Weißensee Academy of Art Berlin have revolved around the history of modern, technical and industrial design. In recent years, he has published work on the topic of an East German modernism which derived much of its inspiration from the Bauhaus programme.