Now and then – a Brazilian design school transforms itself

The stories that follow are based on actual events set in the Escola de Desenho Industrial in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.[1]

[1] The story of behind ESDI’s approach to education during its first 30 years of existence is told comprehensively by Pedro Luiz Pereira de Souza in his book ESDI, biografia de uma ideia (Rio de Janeiro: Eduerj, 1996). The present text is a reworking of some of the stories in a book cowritten with Zoy Anastassakis, provisionally titled Design Education and Democracy at the Edge of Collapse.

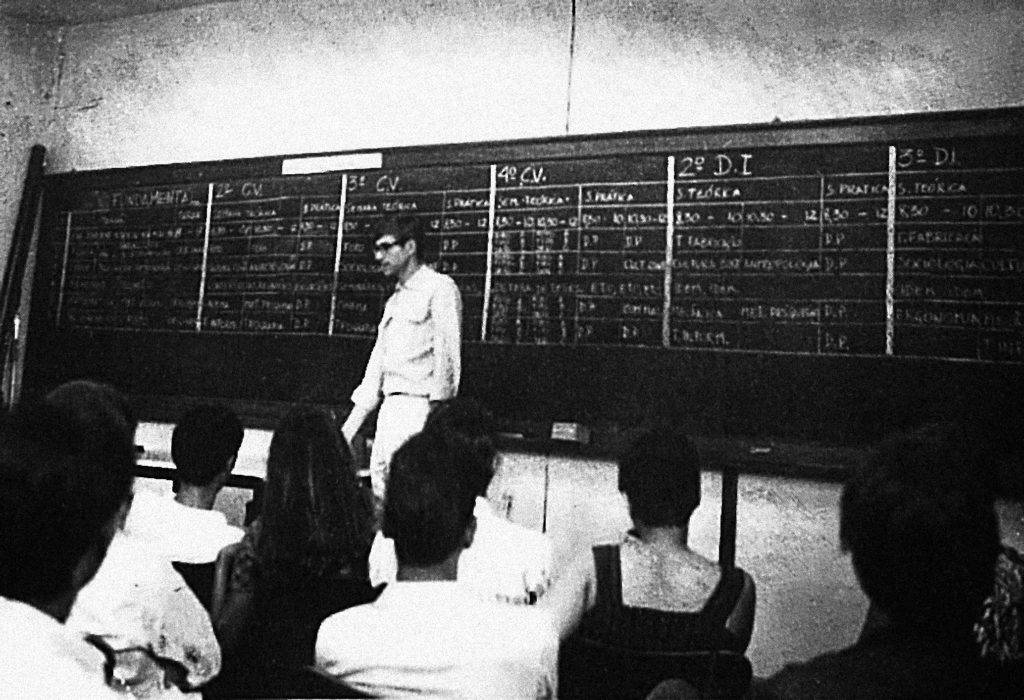

A black rectangle on a white background. Inside the pitch-black rectangle, splitting it into identical columns, white lines stand out, lines so straight they don’t look drawn in chalk. Atop the columns, between the thick lines, the titles come first: Fundamental, 2nd CV, 3rd CV, 4th DI …. Below them, finer lines create additional rectangular fields containing names such as “visual methodology” and “means and methods of representation.” Standing in front of the blackboard, virtually all of the school’s professors introduce themselves and welcome the freshmen. The year is 1968. The place is the Escola Superior de Desenho Industrial – ESDI.

In the audience, a student wearing thick glasses as black as the blackboard, a faint smile revealing most of his big teeth, was excited about what he witnessed. “This has got to be the most solid school in the world,” he thought. He listened intently to the professors’ explanations regarding the course curriculum outlined on the blackboard. The acronyms CV and DI stood for Comunicação Visual (graphic design) and Desenho Industrial (industrial design), the two major fields comprising the subjects students were supposed to learn in the years ahead. The first year was devoted to experience sharing and perception sharpening for the students, who hailed from different walks of life – some were employed with this or that architectural firm, some had come from fine arts courses, and others came from engineering.

The freshman, who had studied a bit of design history, was aware that the idea of a preliminary course descended from Bauhaus’s Vorkurs, which had seen Johannes Itten, in the early days of the German school, set out to steer his pupils toward individual artistic expression through exercises in breathing, concentration and even physical exertion. Over the years, even at the Bauhaus itself, the course lost much of its experimental character. By the time it made its way into the curriculum at the Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm (HfG, Ulm School of Design), the design school regarded as the successor to the Bauhaus, it had become more technical and not as keen on individual expression. The freshman, who was also aware that the HfG Ulm had been a major influence on ESDI’s curriculum, wondered just how much experimentation and technique lurked behind the designation Fundamental (preliminary course). He was thrilled. He wasn’t yet aware he was about to embark on a period of great ebullience, wrought by in-school disputes as much as by the political events that would shake Brazil to its core during that decade.

It had been four years since a coup d’état had ushered in the military regime that would last until 1985. In 1968, Brazilian students were acutely politically aware and highly active when it came to fighting dictatorship. ESDI students, most of whom came from Rio de Janeiro’s middle class, were somewhat engaged in external political issues, but it was when it came to questioning the school itself that they were fiercely critical. The blackboard, which the freshman had found so mesmerizing, sparked rage from an older student he’d just met: “It’s all bullshit. Just more of the same! A crock of shit!” The freshman watched in disconcert as the perfect geometry displayed in the introductory class came crumbling down under the weight of just three sentences. “There’s no criterion at all,” his fellow student ranted on, “these professors think they have the right to decide everything between themselves, with no transparency whatsoever. And then everyone gets scared they won’t be able to keep up, because if you don’t make it through the preliminary course, you simply have to leave the school!” The freshman smiled in embarrassment: “But isn’t there anything good about this curriculum?” “Oh! The preliminary course is kind of cool. You get to make drawings, you learn how to see! We do a lot with our hands, plaster classes, woodworking workshops, that kind of stuff. And these designers that came in from Germany, they really know their stuff, and in some of the theory lessons, you get a lot of relevant political discussion. And we’re free to criticize anything here. Our curriculum, for instance, all but ignores the reality of Brazil. ESDI looks like it was done in a rush, importing a template from the Ulm school.”

The freshman chose not to ask any more questions, because he found it unpleasant that no sooner would the veteran admit to something good than he’d get dragged down again into depressing negativity. He also had his doubts as to whether things were really as his fellow student had described them. It seemed simplistic and unlikely that all of the subjects outlined on that blackboard should be the product of a mere transposition of European principles. The group of professors that delivered the introductory class had pored over the curriculum to make it significantly clearer. With their presentation, they aimed to demonstrate that student complaints had not been overlooked and that there was a genuine willingness to dialogue. However, evaluation criteria remained obscure, which explained the disgruntlement of the veteran and many others, who wouldn’t settle for anything but radical reform. They wanted a full halt and the creation of an eminently self-critical space of discussion. And they got it.

As of June 1968, dean Carmem Portinho consented to shutting down all classes. A routine of meetings between professors and students was put in place and dubbed the “general assembly.” Thus, the classroom became a forum for speeches, conversations and heated debates supposed to yield a curriculum that would address the various problems that had been identified. In short, these problems stemmed from inadequacy of the Ulm template to Brazilian needs, lack of coordination between different subjects and an authoritarian system of admission and evaluation.

In July of that year, the dean released the schedule for the semester, allowing curriculum and school regulation reassessment work to continue in tandem with the regular course. She also proposed a series of conferences with outside lecturers, which would often appeal more to students than so-called regular classes. One day, the student in black glasses, now into his second semester, saw all his fellow students stand up, interrupting the professor mid-sentence. They hurriedly grabbed their belongings and left.

“Come on, the poet’s about to teach a class,” the older student called out.

“But what poet?”, the student inquired.

“Oh, the guy is groovy! He’s part philosopher, part provocateur, I don’t know, all I know is he’s a guy with sensational ideas.”

“But wait, if he teaches here, why wasn’t he at the introductory class with the other professors?”

“He wasn’t there because he’s our own thing, it was us students that brought him here, he’s not even officially on the payroll but he teaches classes here.”

The professor who’d been left with his mouth agape mid-sentence swallowed his pride and set off with the students to attend the poet’s class. Like some of his peers, this professor found the informalities and misbehaviors typical of that time somewhat refreshing, affording a freedom that both physically and symbolically ensured the continuity and circulation of free thinking in military-ruled Brazil.

But the impetus of that year of 1968 also waned. Many of the proposed reforms were not really adaptable to the unyielding institutional forms in place and ultimately proved unfeasible. As a result, even though it had been approved, the curriculum reform did not prevail, and after a few topical attempts it fell by the wayside. However, the massive array of extracurricular activities, the free flow of students between classes, the events, the workshop activities and especially safeguarding of the coexistence myriads of opposing opinions in constant debate had already transformed the school’s repertoire and history. As for the student who at first had been impressed with a neatly presented curriculum on a blackboard, the general assembly experiences afforded him a glimpse, albeit momentarily, into what a design school might be, beyond the grids and the educational approaches. He also learned that design and politics were indissociable.

Where he lived, no one had much interest in a college education. His mind was set on going to college, even if he had to muster the courage to face his parents, who did not encourage him to pursue a higher education, let alone display any willingness to meet the costs thereof. He planned on getting some job to be able to afford a private college on his own. He joined a prep course for college admission exams. In one of the classes, he learned something that took him by surprise and excited him: there was something called a quota system [2] at Brazilian public universities that saw grants given and placements set aside for black students such as himself. He was taken aback: prior to joining that course, he’d never heard of that system from the local news, posters, TV ads or conversations in bars. In communities such as his, the Brazilian government’s affirmative action system was virtually unheard of.

The quotas changed everything. He’d never even considered going to a public university because he knew they were very hard to get into, and competition was fierce. Contradictorily, in Brazil, the wealthy middle and upper middle classes were the ones that made it into these renowned universities because they’d had the privilege of attending private elementary and secondary schools. By setting aside placements for low-income social strata, the quota policy enabled people like this student to compete exclusively with others in similar situations and with similar backgrounds. It was also in the prep course that he heard about Escola Superior de Desenho Industrial of the Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro and about design as a profession. His parents were startled by the word “design”; they feared professions connected with the uncertain field of the visual arts. But he went ahead anyway, never knowing that although affirmative action had made it possible for him to get into college, it couldn’t spare him a violent clash with behavioral codes and cultural repertoires that were completely alien to him.

The first day of class, as soon as he walked past the ESDI gate, he felt relieved to leave behind the hubbub of people rushing along the sidewalk that led to the school. Facing him was a concrete patio of about 50 yards, and then the houses where he’d soon take his first classes. As he walked alone across the patio, on his left he saw the big wooden lettering, E, S, D, I, staked rather flimsily on the short, unmanicured lawn. A few steps ahead and behind him, other students walked, as well, towards the houses. The people were strange. He didn’t speak to anyone that first day, and he didn’t say much or make friends in the months that followed.

He soon realized those young people “listened to a different kind of music” and “wore different clothes.” At lunch break he’d wonder: “How am I going to survive here?” He’d see groups of students and professors walk past the gate towards the nearby restaurant. He could barely navigate or orient himself in this part of town, and he feared going out the gate and not being able to find his way back. At any rate, he didn’t have the cash to afford even half a meal at that restaurant.

The simple self-perception of his body cohabiting a space with other bodies that profusely exuded the signifiers of a culture and a lifestyle he hadn’t had access to made him flinch somewhat. In class, professors would speak familiarly of places unknown: Bauhaus, MoMA, the Louvre. The absence of any introduction to those references showed him it was taken for granted that everyone should know them. His feeling of inadequacy would grow stronger when he’d hear rich students knowingly mention those same places. He could tell by their pronunciation that not only did they know, but they could also speak the languages of the countries where Bauhaus, MoMA and the Louvre were. He could also tell everyone was expected to have a computer, to be familiar with design software, to have the money to buy basic materials and to pay for services essential to the completion of tasks such as high-quality printing. Finally, another aspect definitely caused him to feel the school’s structural elitism in his bones: unlike the middle- or high-class students who got to choose when they’d begin to intern or work, he had to split his time between school and some job. His grant could only get him on the bus from home to a train station, from where he still had half an hour’s walk before getting in the classroom. For a quota student, getting to school remains a huge challenge involving a lot of problems. Has it always been this way?

During the school’s early years, the admission process was extremely thorough. Whoever wanted one of the 30 seats made available per year had to undergo a strenuous selection including a foreign language exam, a native language exam and an essay, a drawing test, a culture and general knowledge test, and finally an interview. Year-one statistics show who got admitted: only 10 high school students, with most of the remainder having or pursuing degrees in architecture, fine arts, professional designers and some advertising professionals. Out of 30 students admitted, 25 were male and 5 were female. None were black.

Considering such a homogeneous set (at least when it comes to financial status and cultural background), it would probably be easier to assume that an education in design was meant for those familiar with words like Bauhaus, MoMA, and Louvre. Once hegemony in background and socioeconomic standing was in place, student evaluation criteria would also be linked to a desired standard of quality (even though it may have been unclear to students what exactly was meant by “quality”). Students’ shared backgrounds would also allow the school to dedicate itself to debates on topics such as the modern project of progress, the future of design in Brazil, and the role such a school could play in national development.

The arrival of quota students presents another shot at social change, beyond grand plans and modern projects. They bring changes born out of interpersonal relationships, indissociable from experiences had at a micropolitical level. The simple coming together, in a learning space, of the elite and historically neglected people undid the hegemony of the student body that had been in place during the early years of the school. The arrival, presence, and departure of quota students at the public university give us the privilege of the raw, physical fact of the coexistence of people with extremely heterogeneous bodies, repertoires, desires, references and responsibilities. This encounter triggers daily events of transformation, in a school hereditarily linked to a European project.

[2] See Sistema de cotas. UERJ – University of the State of Rio de Janeiro, accessed May 27, 2019, http://www.uerj.br/a-uerj/a-universidade/sistema-de-cotas/

is a designer and associate professor at the Escola Superior de Desenho Industrial (ESDI) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, of which he was deputy director from 2016 to 2018. His post-doctoral research at Princeton University investigated social media’s interface design through a historical and critical analysis. Together with Zoy Anastassakis, he authored a book published in the Bloomsbury series Design in Dark Times about a time of crisis and experimentation in which they were at the helm of ESDI.