The empty and the full. Design education, modern design pedagogies and student protests in 1968 Brazil

“The ESDI pavilion discussed what design was, what design was in Brazil and for Brazil. We wanted, among other things, that the school turned itself to the Brazilian reality.”[1]

[1] Maria Valderez, in: Ana Luiza de Souza Nobre: Carmen Portinho: o moderno em construção, p. 130. Rio de Janeiro: Relume Dumará, 1999.

The Escola Superior de Desenho Industrial (School of Industrial Design, ESDI) in Rio de Janeiro was inaugurated by a state government initiative in 1963. It is considered one of the first and most important modern design schools in Latin America.[2] During the post-war period, industrialization had grown 16 percent per year, a feat that placed Brazil first in this sector in Latin America.[3]

ESDI opened amidst the euphoric industrialization effort and economic development promoted by President Juscelino Kubitschek, who built Brazil’s modernist capital Brasilia from 1956 to 1960 under the motto of “50 years of progress in 5.” Local post-war economic development also resulted from the United States’ expansionism over the American continent, with US multinational companies, industrial products and cultural institutions becoming dominant in Brazil.

State authorities and managers, however, had loftier expectations for the school. State governor Carlos Lacerda noted that ESDI’s role in Brazil’s development was “to form personnel and nationalize the form.”[4]

[2] Silvia Fernández. „The origins of design education in Latin America: from the HfG in Ulm to globalization“, in: Design Issues; 22, Nr. 1; 2006; S. 3–19.

[3] Flávio de Aquino. „Escola Superior de Desenho Industrial“, in: Revista Módulo: arquitetura e artes visuais no Brasil, 34, August, 1963, S. 32–38.

[4] Ana Luiza de Souza Nobre. Fios cortantes: projeto e produto, arquitetura e design no Rio de Janeiro (1950-70). Dissertation, PUC-Rio, 2008.

For Mauricio Roberto, ESDI’s first director from 1963 to 1964, industrial products designed at ESDI would help the country “stop paying royalties on imported patents and make aesthetically beautiful objects of use not the exclusive enjoyment of a privileged minority.”[5] ESDI, therefore, had the mandate to give Brazil its own “form” –functional and aesthetic – while freeing the country from the financial clutches of multinationals. This mission was assisted by the fact that ESDI remained autonomous in its organizational and pedagogical structures during its first decade. Not subordinated to the industrial sector or other educational institutions, ESDI became a significant arena from where Brazil’s economic and industrial dependency was critically challenged in the 1960s. Amidst rampant developmentalism, political turmoil and cultural effervescence, the implementation of modern design pedagogies in Brazil was also challenged at ESDI – mostly by students, as we will discuss in this article.

[5] “Desenho Industrial: inscrições até dia 5.” Diário de Noticias. July 3, 1963, B5.

Max Bill famously stated that the designer in post-war industrial contexts was responsible for transforming society through a set of interventions in form-making and manufacturing processes “from the coffee cup to the housing estate.”[6] Bill, the former Bauhausler who from 1953 to 1956 directed the Hochschule für Gestaltung (HfG, Ulm School of Design) in Ulm, Germany, was well-known in Brazil. His artworks were exhibited and awarded in São Paulo’s Museum of Modern Art and Art Biennial in 1951, when Bill’s fruitful exchanges with Latin America gained momentum with further visits in 1953 and Brazilians traveling to the HfG to study with Bill.

The HfG’s exchange with Brazil included also Otl Aicher’s and Tomás Maldonado’s visual communication course taught in Rio’s Museum of Modern Art (MAM) in 1959, which was attended by Goebel Weyne, a future ESDI teacher.[7] The sentiment that a pedagogical genealogy existed between the two schools has its roots in the late 1950s.

[6] Max Bill. Speech at the topping-out ceremony for the first construction phase of the HfG, 1954. https://hfg-archiv.museumulm.de/en/the-hfg-archive/history

[7] Ana Luiza de Souza Nobre. “Ulm-Rio: questões de projeto.” Simpósio ENANPARQ: Trabalhos Completos, 2010, p. 13. http://www.anparq.org.br/dvd-enanparq/simposios/67/67-274-1-SP.pdf

By late 1962, when ESDI’s pedagogical model was being discussed, a few HfG alumni in Brazil were ready to implement their view for design – which from hereon we will call “modern design,” that is, an activity for social transformation via industrial culture and aesthetic. This implementation included the adoption and adaptation of the HfG’s curriculum and to some extent that of its predecessor, the Bauhaus. At ESDI students underwent a one-year “basic course” intended to train their aesthetic learning through skill development in theories of perception, technical drawing, visual methodology or exercises in 2D and 3D techniques in addition to physics, maths, and photography. Curiously, students spent nearly half of their first year attending workshop activities to advance familiarity with materials, a “learning by doing” Bauhaus legacy. The basic course though was also eliminatory. Those who passed it began a three-year specialization in industrial design or visual communication. Here, ESDI differed from the HfG as no specialization in architecture or industrial construction was offered.

Two HfG graduates were central to the development of modern design in Brazil and ESDI’s affiliation to the modern design’s credo of industrial culture and aesthetic: Karl Heinz Bergmiller, a German industrial designer who studied and worked under Bill before migrating to Brazil in the late 1950s, and Alexandre Wollner, a Brazilian graphic designer who went to Ulm to specifically study at the HfG. At ESDI, Bergmiller coordinated the industrial design specialization while working extensively as a product and exhibition designer and as MAM’s exhibition director. Wollner, another prolific professional outside the school, coordinated the visual communication specialization. Goebel Weyne, who taught visual communication, also actively contributed to the development of modern design inside and outside ESDI for decades after the 1960s.

It would be inaccurate, however, to characterize ESDI’s pedagogical model and curriculum as copied or imported from the HfG, especially during its first decade. Firstly, ESDI comprised teaching staff from varied professional realms – journalist Zuenir Ventura, art critic and curator Frederico Morais, artist-turned-graphic designer Aloisio Magalhães, to name a few. They were active in diversifying the school’s approach to mass communication, media and information theory. Others, like Daisy Igel, offered a view for design and design education that even competed with that from the HfG. Igel, an architect and New Bauhaus graduate, had studied under Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Richard Buckminster Fuller, and Konrad Wachsmann, and had worked closely with Josef Albers. At ESDI, Igel promoted “intuitive experimentation”[8] more akin to the Bauhaus’s art-driven and self-expressional approach to design.[9] She taught the basic course’s visual methodology through a sensorial rather than systematic approach to visual learning before leaving the school in 1968.

The other reason why ESDI’s pedagogical model and curriculum differed radically from the HfG’s lies in Brazil’s troubled political, social, and cultural situation in the 1960s, a historical dimension central to our discussion in this article. While state authorities, school directors and HfG alumni promoted modern design as a way for Brazil to overcome economic underdevelopment, design students in 1968 challenged the modern design credo, as we will soon discuss.

[8] Ana Luiza de Souza Nobre, 2010, p. 19.

[9] Holt 2019, 140

ESDI has always been a small school and, until recently, a privileged one. Located in central Rio de Janeiro, it occupies a large walled lot with low-rise houses for classrooms and workshops (figure 2). To date, the school admits only one class of students per year. Between 1963 and 1968, a maximum of 120 students would have passed through its gates. Then, the teaching staff were not much older than the students and both came from a privileged socio-economic background. Students and teachers were mostly white, male, and “intellectually sophisticated,” as it would have been commonly put. ESDI’s social makeup did not reflect that of Brazil’s majority. Only in the 2000s, the school’s class and social demographics changed substantially after a state-driven affirmative policy guaranteed admission quotas for black and low-income students from state-run schools.

When interviewed for this project, Patricia Aquino (admitted in 1966) likened entering ESDI to an adventure. Before 1966, “ESDI had not yet graduated a cohort, no one really knew what the modern designer profession was or could be … students who attended the school in its first years of activity were adventurous,” she says.[10]

ESDI’s admission process was lengthy and demanding. Applicants were required to pass a Portuguese and a foreign language test, undertake a vocational test, and answer an intriguing set of questions to assess an applicant’s “nível cultural” (or cultural level), a phrase that evidences the classism and cultural bias guiding ESDI’s student selection. This “cultural test” included open-ended questions, as the ones found on the qualification exam papers from 1968 (Exame de Habilitação 1968): “To which schools or movements are the following names linked: a) William Morris, b) Hermann Muthesius, c) Walter Gropius, and d) Max Bill?” or “Distinguish between mass culture and mass communication.”

These were devised to sift through applicant’s general and specific knowledge and assess their ability to respond succinctly and critically. In the final stage of admission students met a five-staff panel for an oral examination where they were asked further thorny questions. Aquino recalls a friend who was asked what she thought of a chair, and she said: “I can’t say anything, I haven’t sat in it,” an answer that led her to be accepted by the panel and which evidences an admission process marked by uncertainty and subjectivity.

[10] Patricia Aquino. Interview with Clara Meliande, August 12, 2021.

The first cohort graduated in 1966. Called “guinea pigs” by Flávio de Aquino (ESDI director, 1964–1967), they were set to become the “first national designers” who would be the “first teachers at the future design schools that will certainly emerge in Brazil.”[11] It is crucial at this point to contrast the official discourse sustaining ESDI’s establishment with what happened inside the school in those first five years of activity. For Lacerda, ESDI would “nationalize the form” while for Roberto the school would give Brazil its “own form.” Both assertions implied a lack of aesthetics at a national level. Similarly, for Flávio de Aquino ESDI introduced many “firsts” in a national context for design that according to him was only emerging. However, several professionals from different backgrounds – fine arts, architecture, engineering and technics – were designing, even if by other names. Moreover, scrutiny of the creative life inside (and outside) the school betrays the idea promoted by officials of an emptiness that needed filling.

Good evidence that ESDI (and the Brazilian society more generally) were rather full of aesthetic experimentation and cultural responses to issues raised in the period lies in the exhibition and lecture series “The Brazilian Artist and Mass Iconography” (O Artista e a Iconografia Brasileira de Massa, figure 3). This school-wide event was held in the first semester of 1968 and was linked to art critic Frederico Morais’s contemporary culture course. It was organized by students and teaching staff as a critical engagement with Brazil’s mass culture and communication systems. The event brought together television celebrities, performers, filmmakers, designers, and fine artists, many of whom already populated ESDI and turned it into an vibrant hub of creativity and cultural life. In the early 1960s, Brazil was experiencing some of its most lasting and significant cultural breakthroughs, among them Tropicália (tropicalism) and Cinema Novo (new cinema).

Tropicália – a movement that spanned music, art, design, film, theater, and literature – mobilized seemingly disparate popular and avant-garde cultural forms, national and foreign references resulting in a unique cultural and aesthetic affirmation. Similarly, the Cinema Novo movement experimented extensively with new forms of filmmaking, foregrounding some of the country’s specific socio-political contexts to create a particularly Brazilian aesthetic in cinema. Some of Cinema Novo’s most radical films were in fact edited at ESDI’s editing suite, and several exponents of the Tropicália movement like Hélio Oiticica and Lygia Pape exhibited and lectured at ESDI. Initially scheduled for March, the “The Artist and Mass Brazilian Iconography” event was postponed several times until opening on April 18, 1968. The delay happened not because of the students’ incompetence but because of external events that, in Morais’s words, “turned the national life into mourning.”[12]

[11] Carlos Dantas. “ESDI: entrevista com Flávio de Aquino.” Correio da Manhã: Coluna de Itinerário das Arte Plásticas de Jayme Maurício. April 26, 1966, B2.

[12] Frederico Morais. “Crise estudantil adia a exposição.” Diário de Noticias, April 9, 1968, B3.

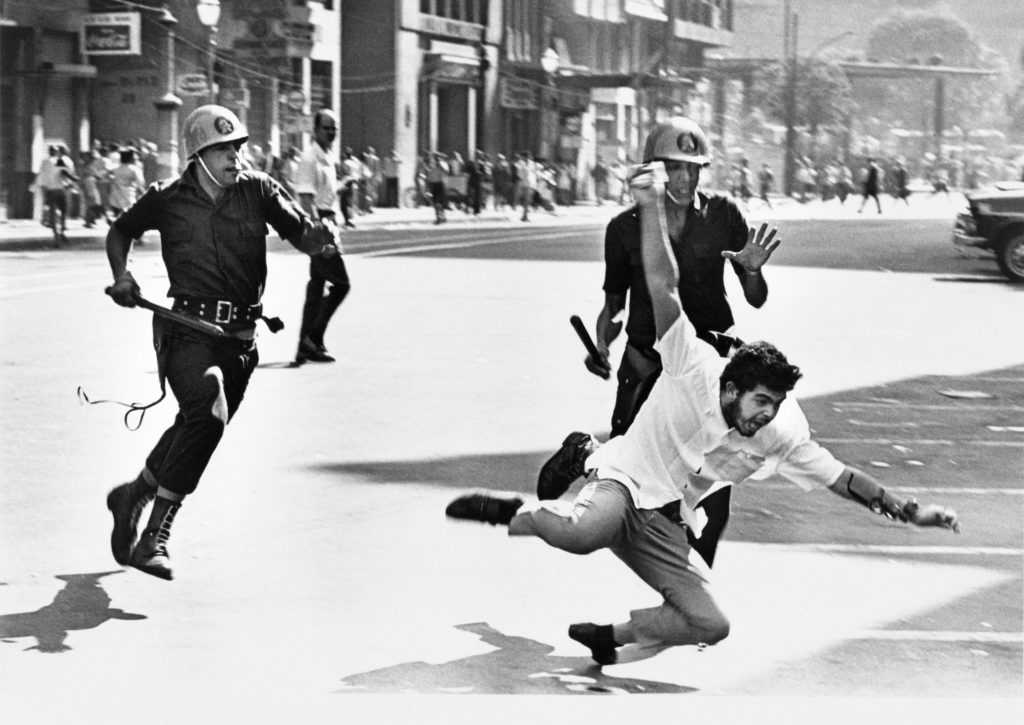

In 1964, a military junta deposed president-elect João Goulart and established a dictatorial state that progressively and violently eroded democratic and human rights in the country, from the vetoing of direct elections to the torture and killing of political dissenters (figure 4). On March 29, 1968, 16-year-old Edson Luis was killed by police inside a student restaurant causing a nationwide wave of mourning and intensifying protest. It was Luis’s killing – the first high-profile case in a dramatic series of occurrences in 1968 – that delayed the opening of ESDI’s cultural events and marked a radical change in the fight for Brazil’s democracy.

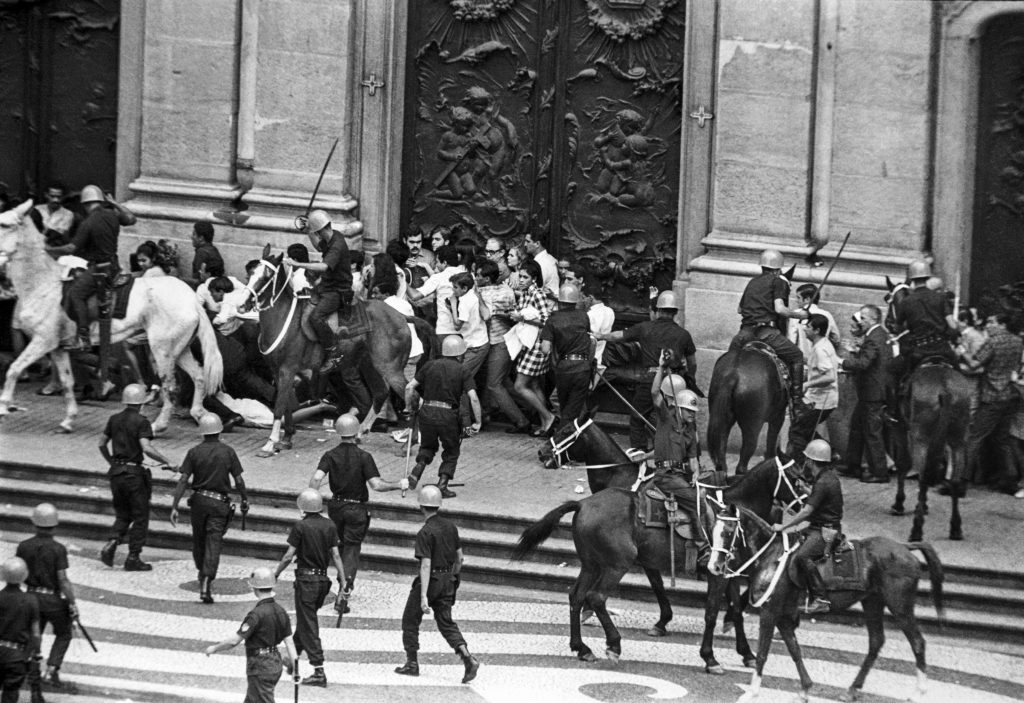

As narrated by Zuenir Ventura, an ESDI teaching staff and author of a key book on the year of 1968 in Brazil, the escalation of police violence – and civil resistance – continued during Luis’s funeral when more than 50,000 people followed the procession and brought the city of Rio to a halt.[13] A week later, a service held in Luis’s memory saw the public – a mix of mourners and protesters – cornered and brutally attacked by police cavalry at the Candelária church, exacerbating popular dissatisfaction (figure 5).

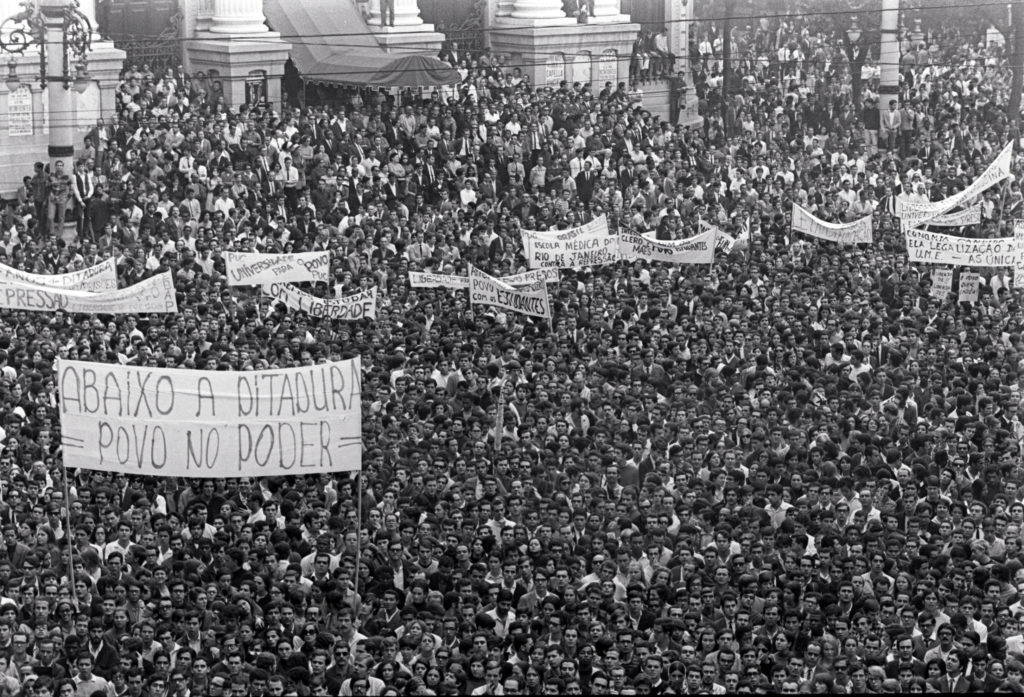

From April 1968 onwards, student meetings usually ended in beatings and mass arrests by the military police, causing further demonstrations and civil retaliation. June 21, known as Bloody Friday, culminated in more killings by the police and mass incarcerations (figure 6). Five days later, the “one-hundred-thousand people march” marked the escalation of unrest when civilians took to the streets demanding the end of the military dictatorship and police violence (figure 7). Educational institutions were particular targets. On September 27, ESDI was invaded by military police armed with gas bombs and machine guns who searched the campus, coerced, and threatened students with arrest.[14]

It is under unprecedented political turmoil that two key incidents in the history of the establishment of modern design in Brazil – and its contestation – happened. From the beginning of 1968 a series of student and staff assemblies were held to discuss discontent with ESDI’s curriculum structure and pedagogical approach. With no agreement, an impasse was reached. In June, students went on strike suspending all regular teaching activities for 14 months.[15]

Yet, in July director Carmen Portinho signed an agreement headed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the military government for the organization of the first International Biennial of Industrial Design in Brazil. Supported by the Brazilian Association of Industrial Design, the São Paulo Biennial Foundation, the National Confederation of Industry, and Rio’s Museum of Modern Art, the biennial was to open in November of the same year – in record time – and host an exhibition by ESDI students. It is at the crossroads of political upheavals, growing student dissatisfaction and an international public-facing event that this history will unfold.

[13] Zuenir Ventura. 1968: O Ano que não terminou. Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira, 1988.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Pedro Luiz Pereira de Souza. ESDI: biografia de uma idéia. Rio de Janeiro: EdUERJ, 1997, p. 154.

After the graduation of the first cohort in 1966, several teaching staff and students increasingly pushed for a reform of ESDI’s curriculum and pedagogical methods. In early 1968 this pressure came to a head: a group of students had failed the basic course in 1967 and were going to be expelled. These students, however, claimed not to understand why they had failed the course. Represented by the student union, they demanded more transparency in assessment methods and accused teachers of employing subjective assessment criteria and of authoritarianism. During the summer months between December 1967 and February 1968, ESDI’s teaching staff attempted at reforming and simplifying the curriculum. New teaching activities and assignments were presented in March 1968 during the year’s opening assembly attended by students and nearly all teaching staff. The new proposal was considered insufficient by the students who persisted in complaining that some teachers were authoritarian and lacked didactic expertise and demanded that one particular teacher be fired.

These were times of crisis and intense work. The March assembly – the first collective effort of management, teaching staff and students to revise ESDI’s curriculum and pedagogical methods – was followed by several other assemblies. Intended to be a retrospective and critical analysis of ESDI’s first five years of existence, these assemblies aimed at devising a common teaching and learning project, but teachers and students frequently clashed, an impasse that resulted in the suspension of teaching activities in June. However, the spirit of experimentation that prevailed during ESDI’s first years led to a creative approach to the strike. Several students carried on meeting daily at the school to discuss the fundamental problems of the school and redefine its future.

One key problem they identified concerned what sort of professional the school was training and how such professionals could contribute to the labor market and in the country’s industrialization endeavor more broadly. Soon after calling the strike, these students embarked on their Labor Market Project to survey, map and analyze labor opportunities for designers. Portinho, alongside teachers like Aloísio Magalhães, supported and guided the Labor Market Project noting that it would underpin the school’s curriculum reform and adapt it “to the needs of the labor market and the reality of the national industrial parks and graphic industries.”[17]

The outcomes of the Labor Market Project were discouraging. Students reported back that job opportunities were scarce, potential employers lacked understanding of the modern profession of the designer and, crucially, that recently graduated designers were faced with the daunting task of having to transform a labor market not ready for them. During an assembly in August, students presented their grim conclusions, calling them “structural dilemmas: ESDI’s implementation had been premature, without attesting to the country’s stage of industrial development.”[18]

As the strike progressed into the second semester and the Labor Market Project evolved, ESDI’s participation in the Biennial was confirmed. Despite being in a state of upheaval, the school needed to plan its exhibition. A group of ESDI students led by Bergmiller and Weyne worked incessantly at MAM to mount the Biennial as a whole. Another part of the school, mostly students, became responsible for the exhibition known as the ESDI Pavilion. Impelled by those crucial questions arising from the project findings, they asked, “Who is designing in Brazil? What is design? For whom are we going to design and how?”[19]

[17] Carmen Portinho. Carta às indústrias. Rio de Janeiro: ESDI Archives, Escola Superior de Desenho Industrial, 1968.

[18] Comissão de Currículo 1968.

[19] Patricia Aquino. Interview with Clara Meliande, August 12, 2021.

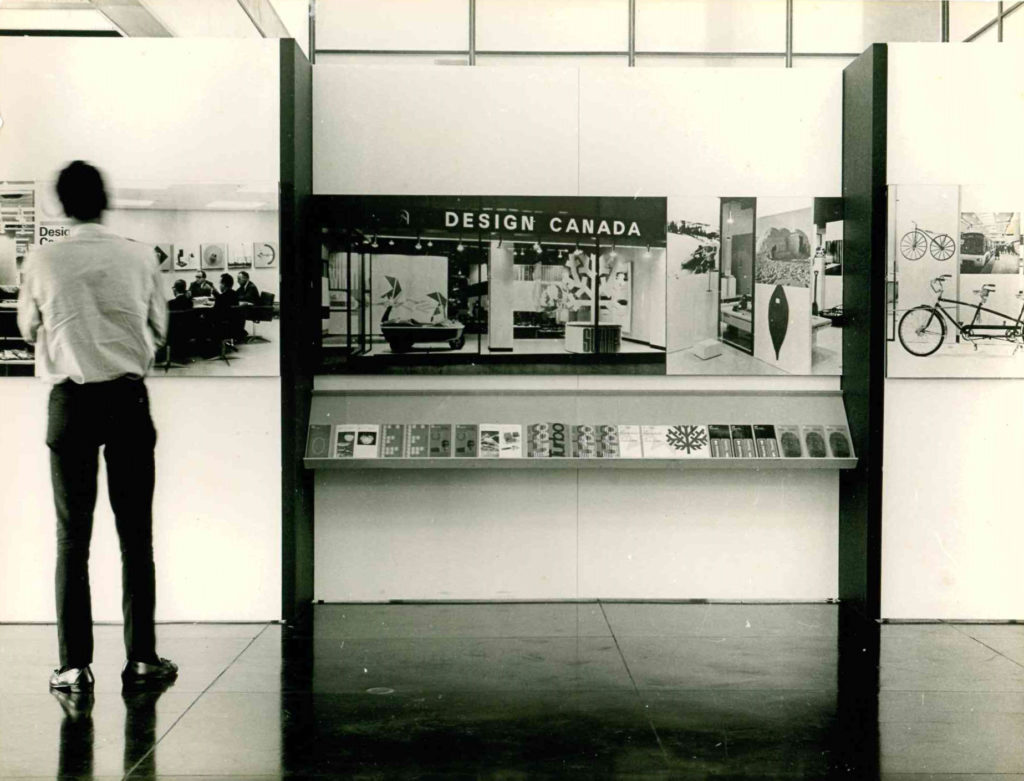

On November 5, the Biennial opened and became a success. It included national and foreign participation. The former displayed industrial design and visual communication works from ten Brazilian modern designers. The latter comprised works from Great Britain, the United States and Canada (figure 8). However, given the haste with which it was organized, rather than of actual objects the Biennial was made up mostly of photographic blow-ups of mass-produced, rationally designed products mounted on panels lining MAM’s modernist open plan galleries (figure 9).

The ESDI pavilion, though, was a different story. In a set of rooms at the back of MAM’s open plan galleries, students displayed their critical analysis of the state of Brazilian industrialization and modern design in the country. By the entrance, a ready-made provocation on a plinth greeted visitors. A “vacuum-broom,” part body and hose of an industrially manufactured, electrically powered plastic device designed for sucking dirt by vacuum, part a human-powered technology made of bristles and wood designed for sweeping (figure 10). In 1968 Brazil, these two technologies were worlds apart. While the broom was ubiquitous, cheap, and intuitive to use, the vacuum cleaner was an expensive and exclusive consumer item representing the hold of the consumer market by multinationals that ESDI students feared they could not overcome. Inside, one of the rooms housed another display, The Banquet of Consumerism (figure 11). This provocation consisted of a long table carefully arranged with a plethora of consumer goods. Here, students used parody to critique the overreliance of modern and industrial design on imported foreign goods in the new post-war paradigm of rampant consumerism.

The ESDI Pavilion contrasted starkly with the “official,” formally controlled, modernist Biennial (figures 12 and 13). Lygia Pape, an exponent of the Tropicália art movement, described this contrast vividly in her article “This Shout Is Ours” circulated widely in a newspaper. According to her, the Biennial was “somewhat grey for Latin tastes, the protocol [is] very strict, the physical aspect of the biennial with panels, texts and few solid objects … has a somewhat metaphysical air to the viewer … A certain aestheticism remained. The exquisite and fine poster has very little popular flavor. But at the Biennial the very tropical ESDI pavilion explodes. Shouts. Humor. Colors trickle down through history. There it is. The emptiness and the fullness. Brazil, importer from the super-mother of the forms that slide between us. And the royalties. And the shout claims the genesis. The noises were heard. The pavilion is important. It is the gestalt of a will. Of a total will … The structure builds itself. The consciousness is founded. It’s the work. Of all. The denunciation progresses. Language will find it. The new language is already a seed. Anthropophagically anthropophagically. Brazilian industry.”[19]

Here, Pape understands the ESDI Pavilion in its cultural context. As with Tropicália, it mobilized seemingly disparate popular and avant-garde cultural forms, national and foreign references in the making of a unique cultural and aesthetic affirmation, this time, for design. It was a full-blown shout inside an orderly exhibition empty of Brazilian culture.

The Pavilion’s reception was contentious. It caused discomfort, drew much attention, was disqualified by some, and applauded by others. For Frederico Morais, it was a “sharp and anarchic critique against the Brazilian industrial process and the industrial design condition in the country.”[20] In the words of one of the pavilion creators, “any student from Ulm could have idealized [the Biennial] … We think that the Brazilian sector is very far from our reality, that’s why we tried in the ESDI pavilion to show the two planes of reality that coexist in Brazil. There is no doubt that good industrial design is a stimulus for production. But it is necessary to be aware of the need to demystify an image of false optimism regarding our industrial possibilities.”[21]

The making of the pavilion took courage. At the height of ESDI’s internal clashing and curriculum reform and at MAM, a national bastion for modernism and “good taste,” ESDI students confronted military ministers, industrialists, professionals, international curators, and the press scrutiny to protest against what they considered to be an “imperialist” design, both on display and the one taught at ESDI.

[19] Lygia Pape. “O grito é nosso.” Diário de Noticias, 19. November 1968, B3.

[20] Ana Luiza de Souza Nobre. Carmen Portinho: o moderno em construção. Rio de Janeiro: Relume Dumará, 1999, p. 129–130.

[21] “Museu de arte tem exposição de desenho industrial.” Correio da Manhã. November 5, 1968, A7.

After the Biennial’s opening, the student assemblies continued at ESDI, with roundtables that brought together professionals from different areas –economists, industrialists, designers – followed by student reports that analyzed and discussed the school’s future. These would have become the basis for the curriculum reform to take place at the end of 1968. On December 13, however, the military government decreed the Institutional Act No. 5 (AI-5), initiating the most violent phase of a dictatorship that only ended in 1985. Through the AI-5, the military junta closed the National Congress and regional assemblies, revoked congressmen’s mandates, suspended the political rights of all citizens for a period of ten years prohibiting anyone from speaking out on political matters, removed civil servants and confiscated assets from individuals and companies. Censorship, torture and killing of dissidents were already current practices, but these intensified with the suspension of the rule of law in Brazil. Brazilian artists, scholars and dissidents went on mass exile abroad.

The environment inside and outside the school became grim, disruptive. The HfG, which had been an example as much as a nemesis, closed at the end of 1968. In 1969, ESDI was emptied: more than a third of the students took leave, several staff members withdrew from their positions. The possibility of a radical pedagogical change faded away. The school tried to return to a situation of normality with less dissent. Some students tried to return to regular activities and their training resumed with some adjustments. Here, we hear echoes with the history of the Bauhaus, closed by the brutal Nazi regime in 1933. In 1968, however, political resistance and the critical spirit of collectivism enabled ESDI to shape its future differently. The remaining students and staff survived and kept ESDI going while military tanks paraded the streets. However, the worst years of the dictatorship were yet to come.

Livia Rezende, PhD (RCA) is a design historian living on Gadigal land and working at the University of New South Wales, Australia. She is the co-founder of OPEN, an art and design decolonial praxis collective, and an international keynote speaker on the history of Latin American design (AIGA, 2021). Her publications feature in RMIT Design Archives Journal (2021), Iberoamericana (2021), Designing Worlds (2016), Cultures of International Exhibitions (2015), Design Frontiers (2014), and the Journal of Design History (2015, 2017) whose Locating Design Exchanges in Latin America and the Caribbean special issue (2019) she co-edited.

Clara Meliande (1980) is a Brazilian graphic designer, researcher, and educator. She often approaches design curatorially, conceiving exhibitions, publications, and educational projects. She is currently a Ph.D. candidate at the School of Industrial Design of the State University of Rio de Janeiro (ESDI/UERJ), and a fellow researcher at the Design and Anthropology Lab (LaDA). Her research interests focus on the history of design education in Brazil, specifically looking at design schools from the 1950s and 1960s, that for various reasons—personal, political, circumstantial—remained unrealized.