The 1928 Chilean Vorkurs: Synthesis between vernacularity and functionality

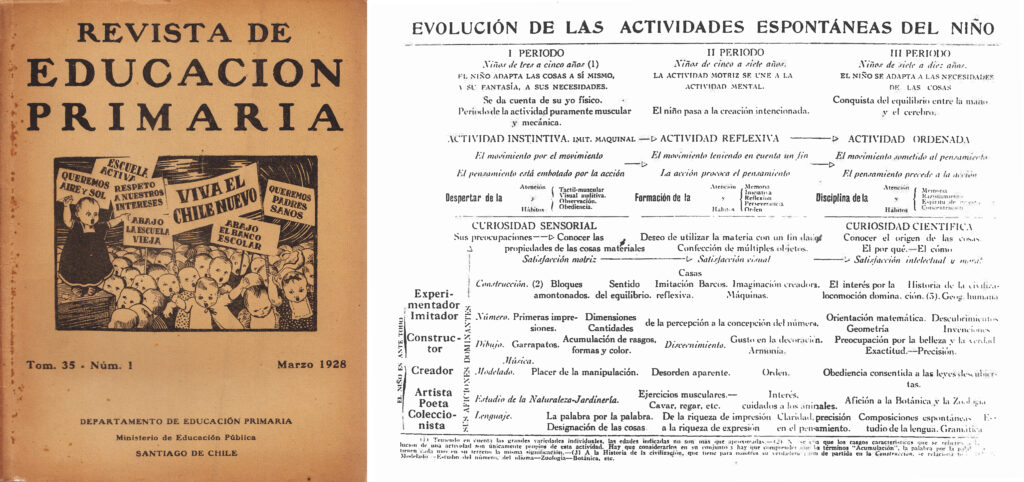

In January 1928, the Chilean government initiated an educational reform based on the theories of the escuela activa (active school).[1] During that reform, the Academy of Fine Arts was included in the remit of the Ministry of Public Education as part of the changes introduced by Professor Carlos Isamitt.[2] He applied a methodology that was equivalent to the Vorkurs or Vorlehre of the Bauhaus state art school at Weimar and the Bauhaus Dessau called primer año de prueba (first-year trial course).[3]

The reform was halted in October of that year, as was the new direction of the school of art in January 1929, but by then it had established the precedent of change in the institutional paradigm regarding the relationship between art, science, new technologies, urbanism, education, and industrialization in the processes of social change taking place in the Chilean state.

The escuela activa relied on the work of the Swiss pedagogue Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi (1746–1827), who focused on the generation of knowledge that acknowledges the students’ own cultural variables. That strengthens their autonomy in the process of interpreting reality in terms of their community and environment. This concept was continued by Friedrich Fröbel (1782–1852) and became crucial for the constructivist avant-garde who questioned the mechanical reproduction of knowledge. Various Bauhaus professors such as Johannes Itten and Hannes Meyer applied the same concept as the escuela activa in relation to the design of interaction and its perception.

[1] Leonora Reyes-Jedlicki. “Profesorado y trabajadores: Movimiento educacional, crisis educativa y reforma de 1928,” Docencia, no. 40, 2010, p. 40–47.

[2] Teresa Navarro Cortés. Carlos Isamitt, paper, Universidad de Chile, 1967, unpublished.

[3] Valerie Hammerbacher, David Maulén. “Vernacular Modernism: Carlos Isamitt and the Founding of the New School of Fine Arts in Chile, 1928”, in: The whole world a Bauhaus, Stuttgart/Munich: Ifa-Hirmer, 2019, p. 157–162.

The concept was further developed in Europe by Maria Montessori, Adolphe Ferrière, Jean-Ovide Decroly, and Georg Kerschensteiner, and in Latin America by José Vasconcelos, José Ingenieros, Carlos Vaz Ferreira, and José Carlos Mariátegui. In Chile, the movement of elementary teachers (normalistas) responsible for the compulsory primary education also followed this educational concept after 1920 with the trade union Federación Obrera de Chile (FOCH), independently and in parallel with the educational programs of the government.

In the wake of the First World War, various societies attempted to move past the contradictions of 19th-century modernity that had led to the greatest armed conflict hitherto known in history. There were exchanges between Chile and Mexico as part of the former’s revolutionary educational reform, and the changes were also observed by the new Weimar Republic.

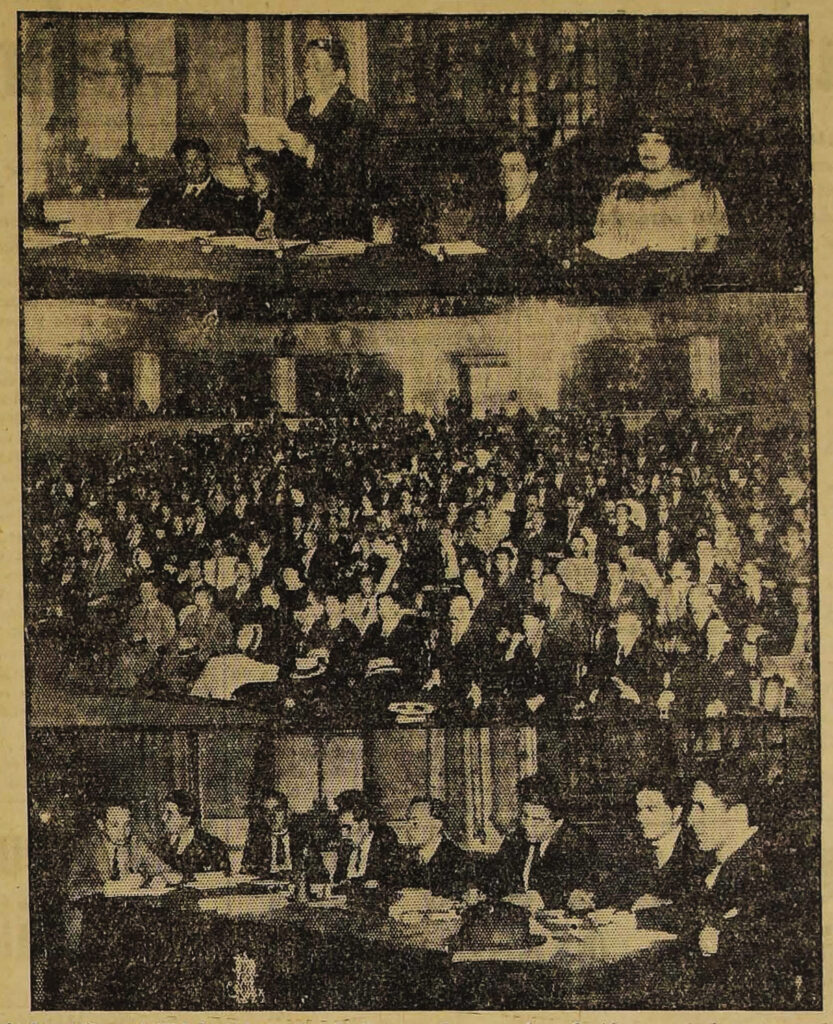

The young German republic’s constitution had been written in the German National Theater in Weimar 1919. This was replicated in Chile in March 1925 at the Santiago Municipal Theater, with a constituent assembly of its own. At its center was an educational reform based on the escuela activa.

Nevertheless, the Chilean president Arturo Alessandri Palma and a small committee enacted a different constitution, leading the betrayed teachers to protest in the streets. General Carlos Ibáñez del Campo assumed the presidency in 1927, encouraging the teachers to transform education in 1928. They considered a range of unprecedented issues for the post-colonial Chilean institutional structures, among them the appreciation of their own culture and the industrialization of education.

The hierarchical, vertical and centralized corporatist state clashed with the autonomy and decentralistic notion of the escuela activa, and it was in this context that the first-year preliminary course or Vorkurs was implemented in the country’s most important institution for artistic education. In 1925, Carlos Isamitt visited Europe as an (ad honorem) representative of the elementary teachers of the escuela activa, in order to examine the curricula of the new schools of art which were oriented towards an industrial application of their products.

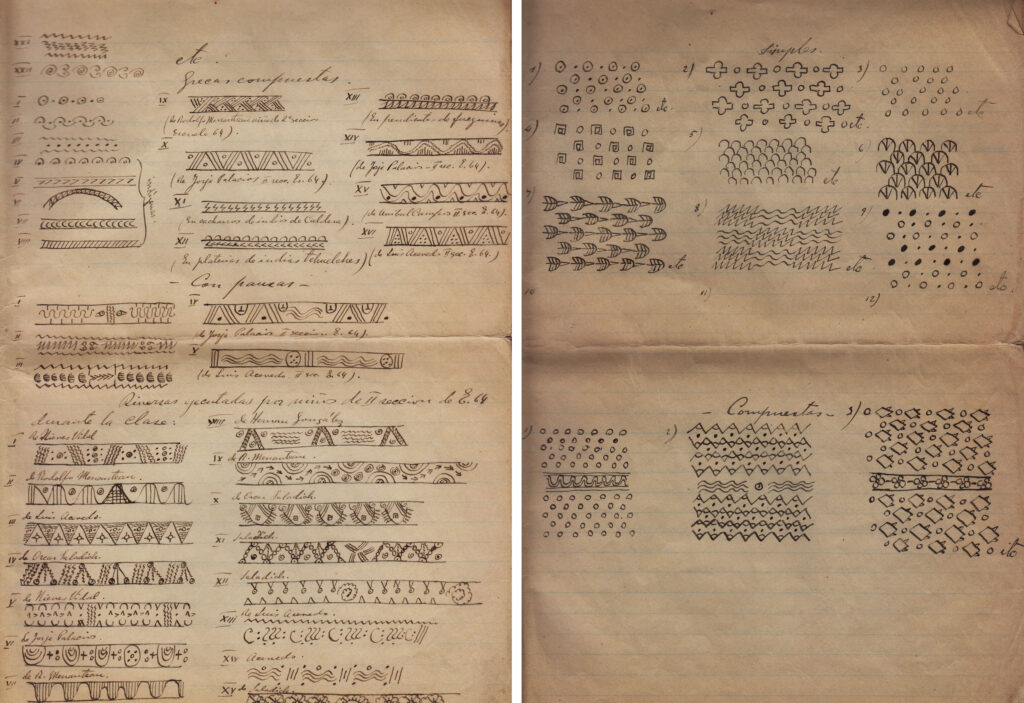

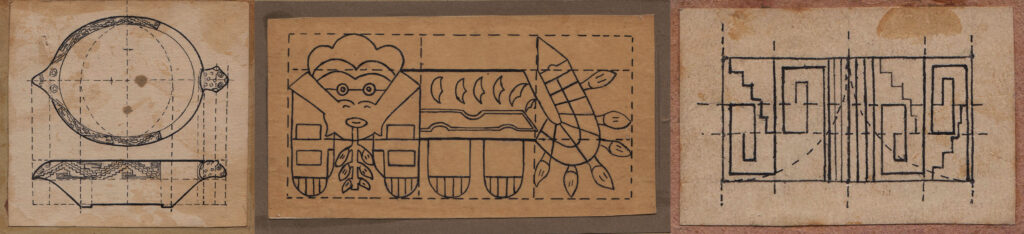

Carlos Isamitt had previously been an ethnographer at a time when there was no institutional appreciation of popular culture or indigenous American art. Between 1910 and 1918, he studied the geometric abstract art of the peoples of southern Chile for the first time, inserting himself into their communities in order to understand their systems of meaning. It was his objective to apply them to teaching children. He also studied pedagogy, fine arts, and music.

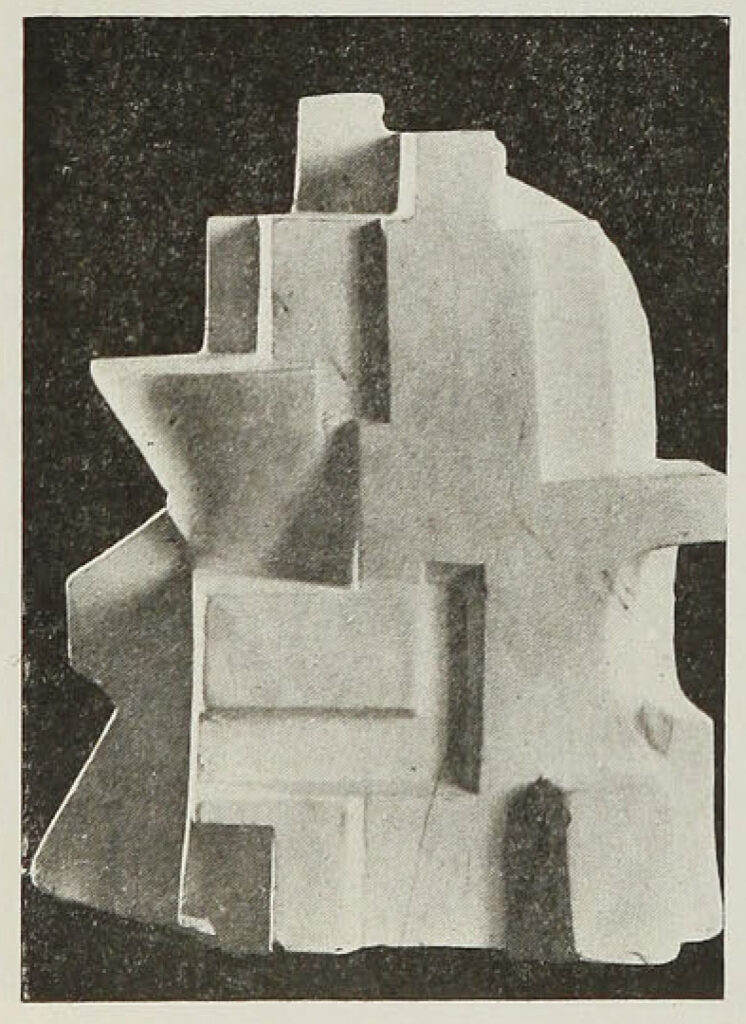

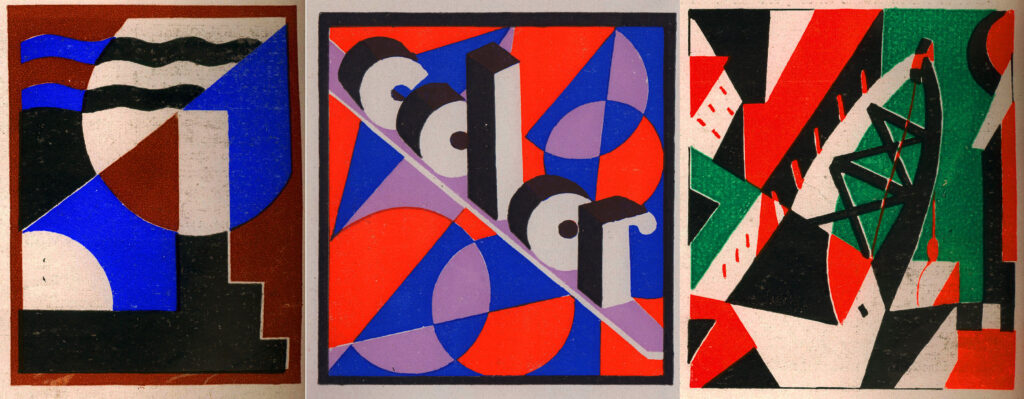

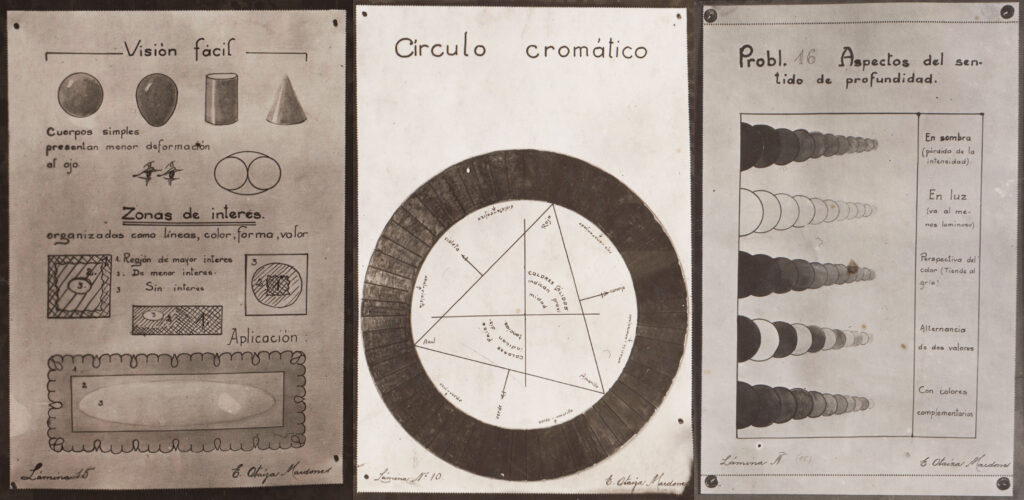

Even though the Chilean artists Clara Werkmeister and Gustavo Keller Rüff had taken part in Johannes Itten’s Vorkurs in 1919 and 1920,[4] the connection with Isamitt was formed at the pavilion of the Soviet Union’s Vkhutemas state art and technical school at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris in 1925: “ The Moscow School of Fine Arts, unified with the School of Arts and Industries, is filled with great zeal for innovations. Any student who wants to prepare for the courses in architecture, painting, sculpture must first be taught, in an elementary section, the principles of color, volume and space.”[5]

In 1925 Isamitt also studied Polish, Belgian, and Austrian schools as well as the theorists Karol Homolacs and Matila Ghyka. Finally, in 1928, he spearheaded the pedagogical transformation of the state’s art education.

[4] Magdalena Droste, Anke Blumm, Media Architecture. “PERSONENSUCHE”, in: bauhaus community, 2020, https://bauhaus.community

[5] Carlos Isamitt. “Las artes decorativas de Rusia, Austria y Polonia. Algunos aspectos que se observan en la Exposición de Artes Decorativas de París, nuevos métodos de enseñanza y nuevas concepciones del arte,” El Mercurio, October 25, 1925, p. 9.

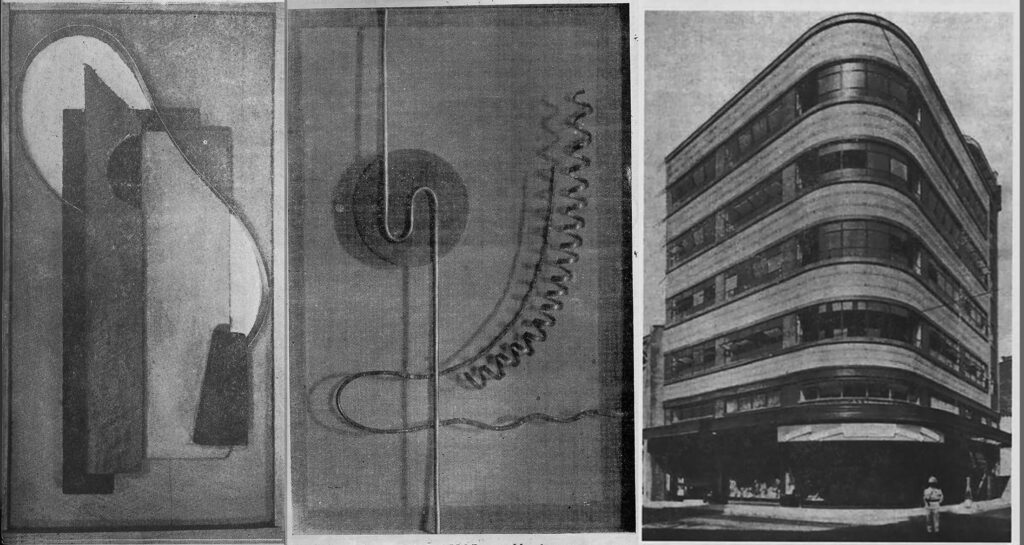

Carlos Ibáñez resigned as Chilean dictator in 1931, and two years later the geometric abstract art group Decembristas emerged, among them Gabriela Rivadeneira, a former student of the 1928 primer año de prueba, and José Dvoredsky, an ex-student of Abel Gutiérrez’s indigenous geometry course at the National Institute during the 1928 reform.

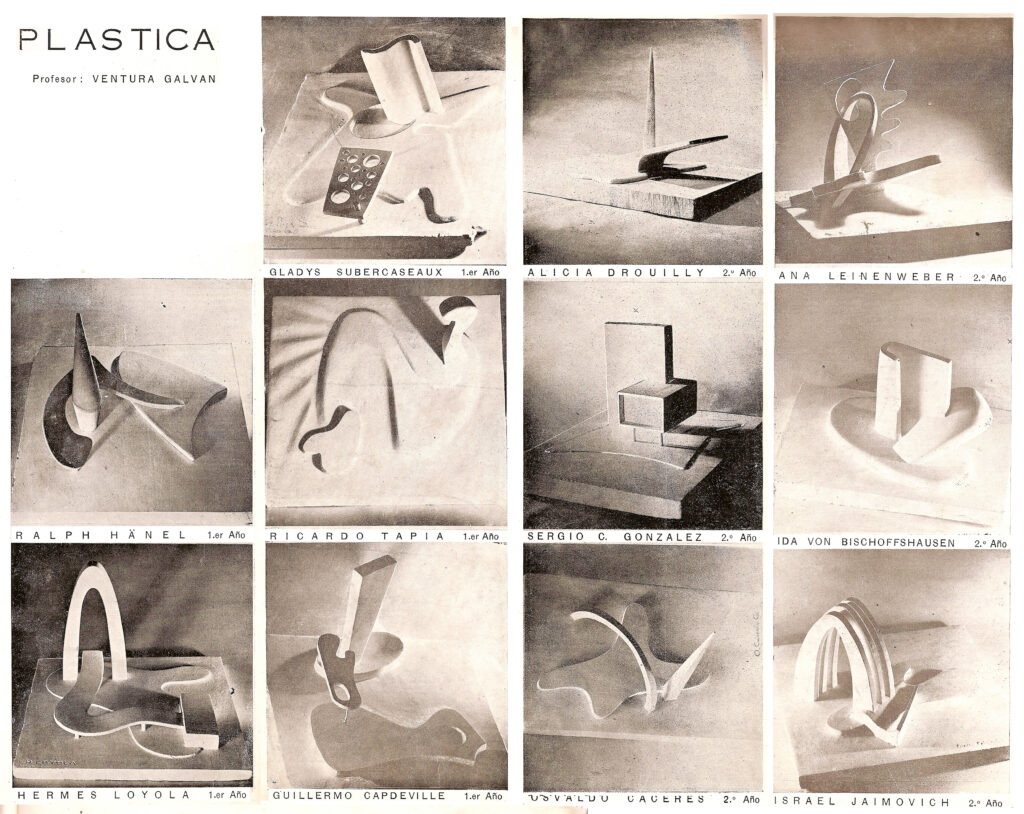

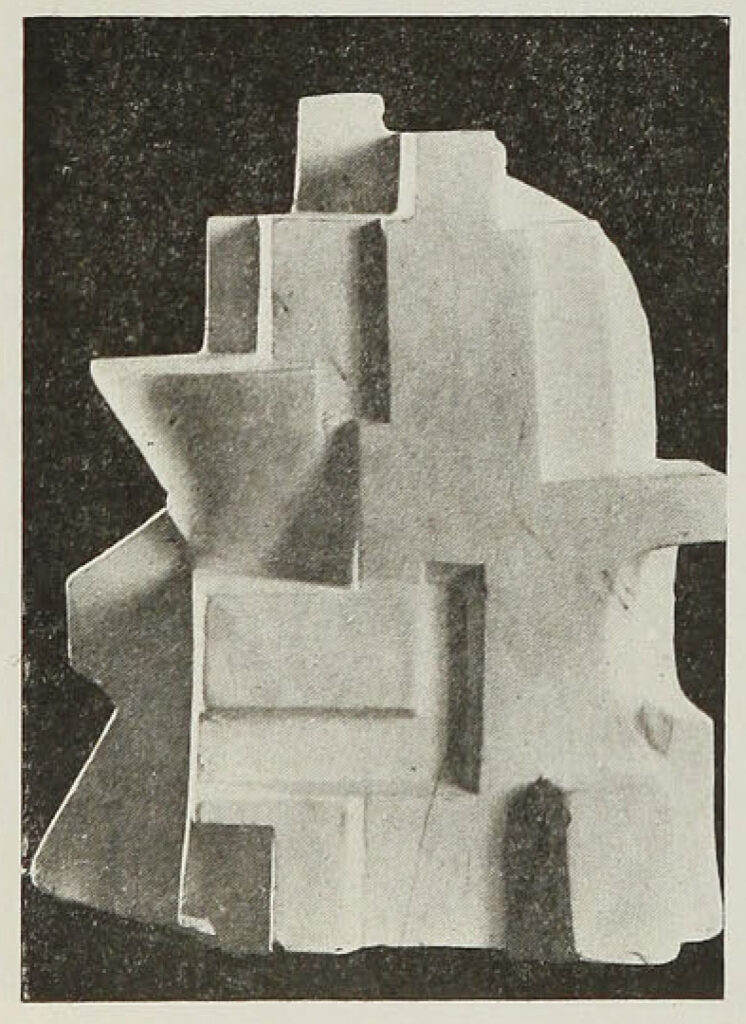

More than a decade later, in 1946, the faculty of architecture at Universidad de Chile implemented a new curriculum inspired by Hannes Meyer’s Bauhaus, in which the “first-year plastic composition” course was directed by Ventura Galván, who took part in the primer año de prueba in 1928. Finally, in 1958, Galván built a School of Design within the new architecture campus, taking over the surviving School of Applied Arts created by Isamitt as part of the 1928 plan.

(* 1974) is a researcher of the interfaces between art, science, technology and society in Chile and Latin America, mainly in the 20th century. He was regional curator of the project “The whole world a Bauhaus,” and has also published on the impact of Hannes Meyer’s Bauhaus in Chile. He is currently doing research on the buildings for the 3rd United Nations Conference on Trade and Development UNCTAD III in Santiago de Chile 1972 and the history of cybernetics in Latin America.