Sándor Bortnyik’s Műhely, the „Budapest Bauhaus”, 1928–1938

Having emigrated from Hungary to Vienna after the defeat of the short-lived communist Council Republic of 1919, Sándor Bortnyik (1893–1976) stayed in Weimar from 1922 to 1924. Although he was not enrolled in the Bauhaus as a student, he had close contacts with Bauhaus people, especially his fellow Hungarian Farkas Molnár,[1] and attended Theo van Doesburg’s anti-Bauhaus class. Prior to approaching the Bauhaus, he had exhibited in the gallery Der Sturm in Berlin, and in September 1922 he attended the Weimar Conference of Dadaists and Constructivists organized by van Doesburg.

Bortnyik’s paintings from the Weimar period are oscillating between constructivism and the satirical critique of constructivism. As a socialist, he was committed to the progressive utopia of geometric abstraction, but he also saw the gradual deconstruction of that utopia in the world of pragmatism. His later activities indicate that, with all the initial difficulties and inner contradictions of the school, he was impressed by the Bauhaus as a model of modern art education seeking actual connections to the world of production. While in Germany, he also experienced the reality of rising industrial and business influences, and, in response to van Doesburg’s views, saw the challenges that this emerging new world meant to the visual arts.

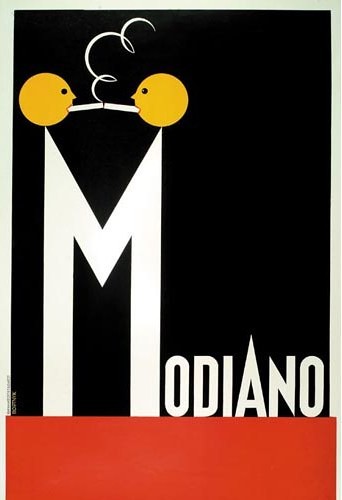

[1] In an interview in 1972, he talked about meeting Molnár in Vienna in 1921 and hearing about the Bauhaus from him. Cf. Iván Rozgonyi’s interview with Bortnyik, “Beszélgetés Bortnyik Sándorral,” in Művészettörténeti Dokumentációs Központ Közleményei, no. III, Budapest, 1963, p. 20–28. In his account written for Eckhard Neumann (Bauhaus und Bauhäusler. Cologne: DuMont Verlag, 1985, p. 144–149) he says he it was in 1922, probably erroneously, as Molnár arrived in Weimar in 1921. ((figure 1))

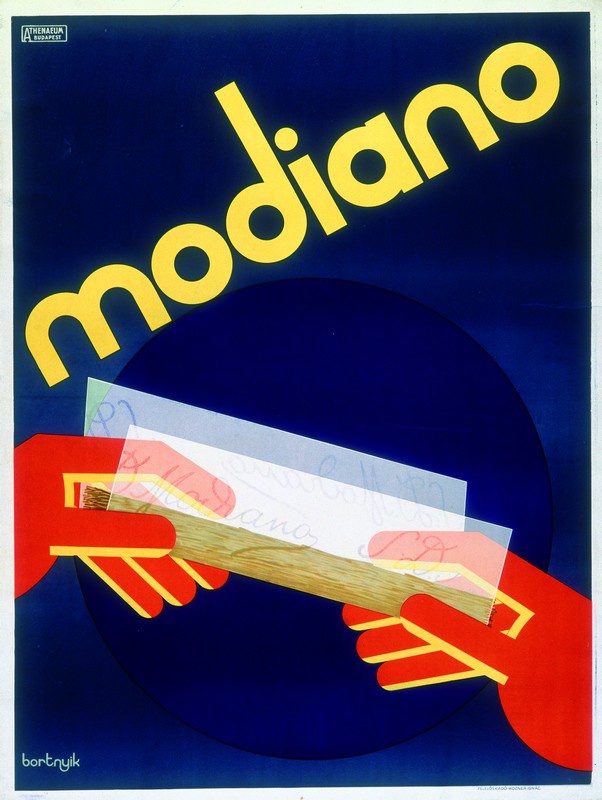

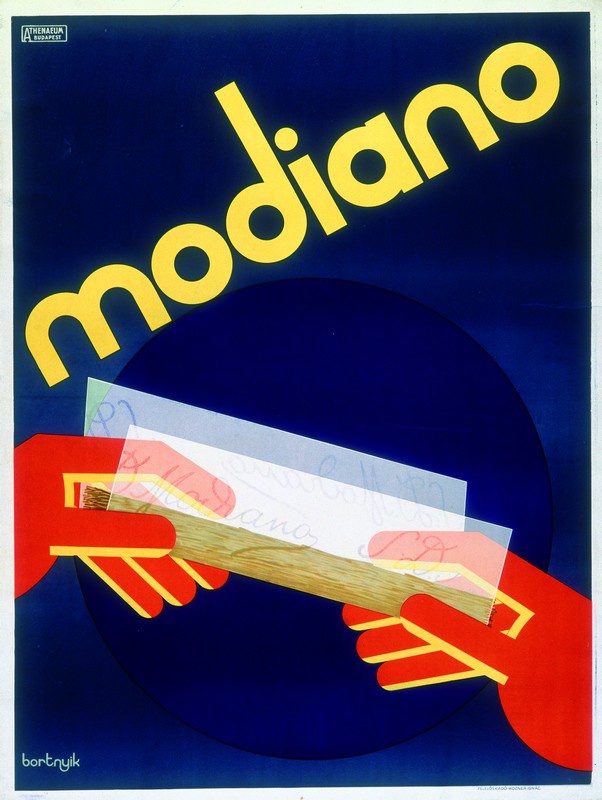

He returned to Budapest in 1925 and became active in graphic design as well as theater work. The commodification of modernity reached Hungary, too, in the second half of the 1920s. Economic competition and a race for market shares made advertisement necessary. New ideas, bold and surprising images and type-faces marked the market-savvy designer who had an intuitive sense of psychology and a knack for succinct, efficient design. Bortnyik assessed the situation writing that “perhaps businessmen play the same role in art today as the churches and rulers did in the Renaissance and baroque ages. … In the design of factory and office buildings, in interior design, but first of all in advertising, which is the propaganda of business life, art has already produced highly valuable works.”[2] Progressive artists saw advertising as a social service to the masses, informing them about new products while helping the industries to reach their customers. Moreover, Lajos Kassák and Bortnyik considered advertising to be the artists’ social responsibility, their stepping out of the ivory tower of pure subjectivity and aestheticism into the actual reality.

Hungarian industrial development followed the German and West European developments with a few years’ delay, but by the second half of the 1920s, foreign-owned as well as Hungarian enterprises were in sharp competition for buyers. Interest in modern graphic design was also palpable. Bortnyik was one of the founders of the Könyv és Reklámművészek Társasága (Association of book and advertisement artists) in 1930. Members included Farkas Molnár, László Moholy-Nagy, and Lajos Kassák. The association was oriented towards constructivism and functionalism. In 1938, Bortnyik became vice-president of the association.[3]

[2] Sándor Bortnyik.”Művészet és üzleti élet,” Új Föld, 1927, vol. 1, p. 11–12.

[3] Katalin Bakos, Bortnyik Sándor és a Műhely. Budapest: L’Harmattan, Kossuth Klub, 2018, p. 104.

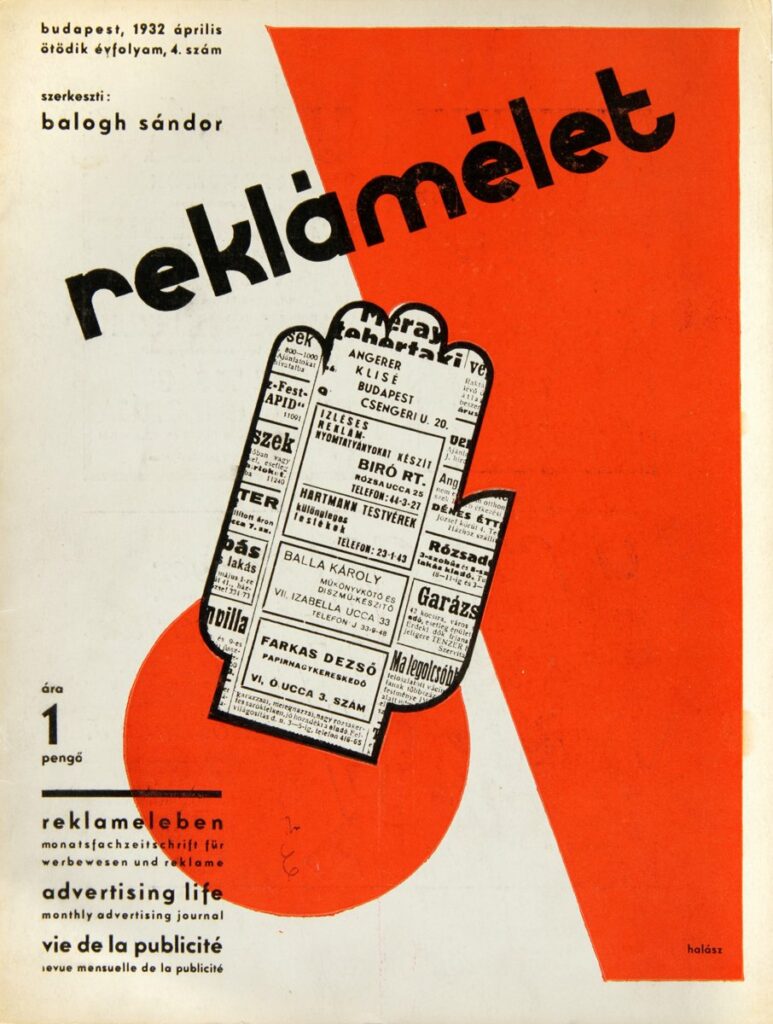

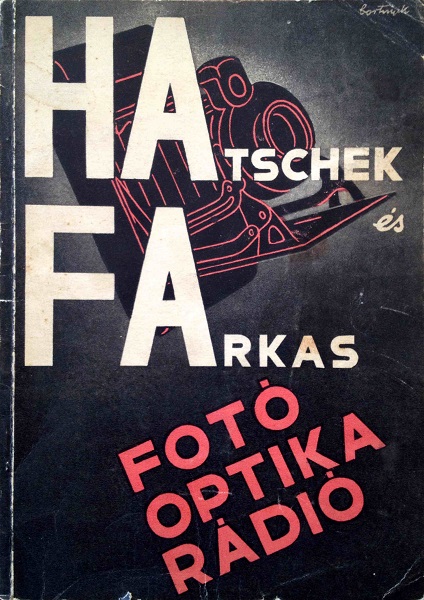

The idea of founding a Bauhaus-type school in Budapest originated as a shared concept from Bortnyik, architect Molnár, architecture critic Pál Forgó, and poet Árpád Szélpál (1897–1987), who first formed the Új építők társasága (Association of new architects).[4] As Bortnyik said in our 1972 interview and announced in several articles[5] about the Műhely (workshop), he planned an ambitious school project whose curriculum was to include architecture, theory, product designs for mass production, history, and graphic design. The school opened in his own apartment in Budapest,[6] far more modestly than his original ideas had been. Its focus was on advertising design. Some of those who attended the Műhely became internationally famous artists in various fields, among them animation filmmaker János Halász (John Halas, 1912–1995), painter Vásárhelyi Győző (Victor Vasarely, 1906–1997) and his wife Klára Spinner (Claire Vasarely,1908–1997), photographer Ata Kandó (1913–2017), her husband, painter Gyula Kandó (1908–1968), or graphic designer and illustrator Vera Csillag (1909–1997). Hungarian animation film artist Gyula Macskássy (1912–1971), graphic designers Tibor Szántó (1912-2001) and György Radó (1912–1994) also studied at the Műhely. Most of the students attended the school’s evening classes as they already worked during the day but needed to update their skills or systematic professional education.[7]

In 1929, the Műhely was moved over to Bortnyik’s studio in Nagymező Street 3. Bortnyik had to give up on the idea of studios for ceramics and architecture for lack of space and financial resources. Even though he was not able to employ prominent artists, he invited Molnár and literary and film theorist Iván Hevesy (1893–1966) to give lectures. The Műhely did not have a finalized curriculum, but Bortnyik used basic geometric forms to teach visual composition and rhythm.[8] In our 1972 conversation he underlined that he followed van Doesburg’s and De Stijl’s aesthetics rather than Johannes Itten’s methodology in the early years of the Bauhaus.

[4] Ibid., p. 129.

[5] Pesti Napló, September 26, 1928, p. 13; Magyar Grafika, 1928, no. 9–10, p. 255–258.

[6] His address was Damianich Street 32.

[7] Bortnyik’s personal communication; also Bakos, op. cit., p. 175.

[8] Bortnyik’s letter to Victor Vasarely of June 24, 1966, is quoted in Bakos, op. cit., p. 138.

The fundamental goal of the Műhely was an effort to legitimize modernist visual language in Hungary in graphic design, first of all in advertising and posters. While there was actual demand for efficient advertisements and a moderately modern visual language was already fashionable in Hungary, this effort also had a leftwing political overtone to it as it was opposed to the conservative, overdecorated mainstream visual language which used nationalist and religious motifs in abundance. Part of the manifestly progressive visual language was the inclusion of photographic details, photography being the state-of-the arts medium at the time.

Compared to the officially accepted and popularized figurative works touting Hungarianness, the simplicity and functionalism of the Műhely designs were internationalist and progressive. The economy of the graphic design works made at the Műhely spelled machine aesthetics, industrial reality, and rational planning. This was reflected by what Jan Tschichold termed „new typography,” applied in the graphic design works of the students at the Műhely: an efficient vehicle of communicating opposition to conservatism.

As Bortnyik summed it up for Eckhard Neumann, his intention was to establish an institution which adopted the principles of the Bauhaus and would have offered education in many different fields. However, he found neither official interest in the project nor private financial support. Therefore, he had to limit the school’s activities to free and applied graphic design in the spirit of constructivism.[9] As the Bauhaus had many Hungarian students and faculty members, it was a valid and telling reference point for an art school such as the Műhely in Budapest. In 1938, by the time many of the students had emigrated, the school was financially no longer sustainable, and Bortnyik had to close it down.

[9] Neumannn, op. cit., p. 149.

is art historian, critic, and curator, Adjunct Professor of Art History at Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, California. She is author of The Bauhaus Idea and Bauhaus Politics, (Central European University Press 1995), and many essays about different aspects of the Bauhaus. She has researched and published on the comparison of the Bauhaus and the Moscow VKhUTEMAS as well as the Hungarian participation in the Bauhaus.