Rooms of departure: From teaching museums to empty walls

In March 2020, the School of Design building in Newcastle, England, was taken away from my students and I. In fact, the world lost their buildings. Offices, shops and educational institutions closed their doors. Metaphorically and physically. Having the defining geographical and intangible boundaries removed from my teaching was one of the biggest challenges I’ve ever faced as an educator. My students, interior design undergraduates, need to feel space, touch it, sense it. They need to understand the capabilities of its volume and how the users will move through and interact with it. Their educational environment offers a daily precedent as they absorb the semiotic information held within it and digest knowledge imparted from within its walls. Whatever the curriculum, it nurtures, supports, offers comfort and becomes a home away from home. And the ability to do all of that successfully rests heavily on the atmosphere created within.

And suddenly my building and its inherent atmosphere was gone.

As I experienced on my first visit to the Bauhaus Dessau, the power of the building to punch you in the stomach while it transports you to the past at the same time as it pulls you firmly into the present, and indeed the future, has never left me. Walter Gropius, founder and architect of the Bauhaus, was certain of the impact that the building would have, but also promoted that a successful learning experience was dependant on more than the individual elements of the architecture and a radical new curriculum. Something else was required. In 1934, on his arrival in England, Gropius was asked by a member of the Design and Industries Association (DIA) to see the Bauhaus timetable, with the thought that the Birmingham College of Arts and Crafts might incorporate it into their timetable. ‘Gropius was horrified: “It would not tell you much”, he replied with scorn, “it was the atmosphere.”’[1]

The importance of this inter-relationship of building and atmosphere in education was a clear vision of Gropius. Independently of this, however, his curriculum and its exercises migrated globally: copied, adapted, reinterpreted and translated as an example of progressive, abstract, reformist teaching. One which gained momentum and gradually altered educational pedagogical principles worldwide in a historic movement. In the 1950s, it arrived in Newcastle, England.

[1] Fiona MacCarthy. All Things Bright and Beautiful: Design in Britain: 1830 to Today. London: Allen and Unwin, 1972.

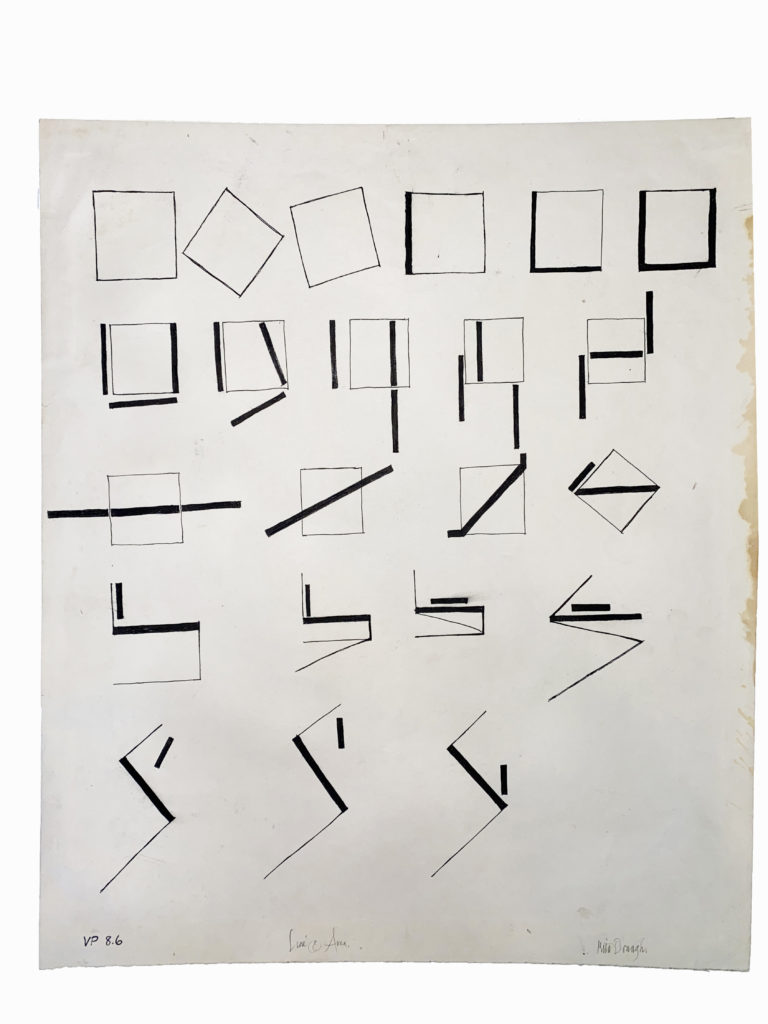

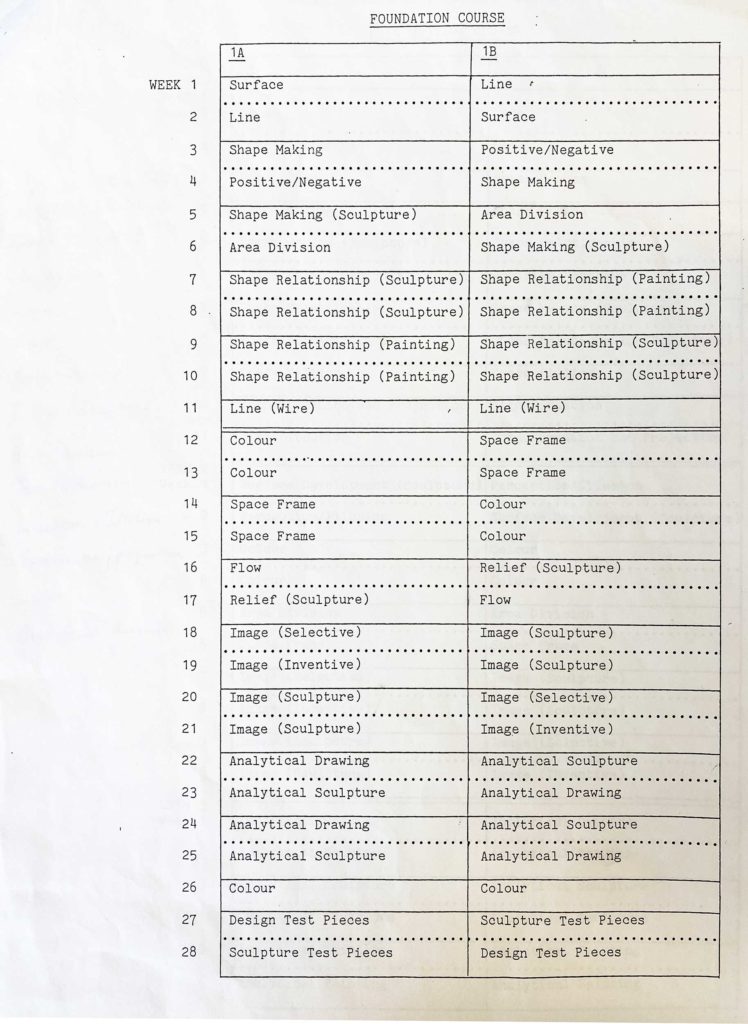

20 years after Gropius left, the pedagogical influence of the Bauhaus was manifest in a radical departure from traditional fine art teaching in the department of fine art at King’s College, based in Newcastle upon Tyne. Under the directorship of Lawrence Gowing and his successor Kenneth Rowntree, from 1954 to 1966 Victor Pasmore and Richard Hamilton were accredited for the design and delivery of the Basic Course, also known as ‘Basic Form’, the ‘developing process’ or the ‘foundation course’. Pasmore, appointed as Master of Painting, was a leading abstract, constructionist artist and was aligned firmly to the fine art course accompanied by Hamilton, an artist and designer initially based in the design school. Founded on the principles of Johannes Itten’s Vorkurs (preliminary course) established in the 1920s and inspired by the principles of Paul Klee in particular, what followed was a profound departure from the model-based teaching seen in the department previously.

In 1958, the Basic Course curriculum appeared as a static list of exercises and lacked any qualitative elaboration as to how students would learn. Though clearly influenced by the revolutionary teaching of the Bauhaus at the time, this was not a copy and in reality, it was presented as a heterogeneous mixture of principles through the exercises set. Pasmore stated ‘it is necessary to understand that there was no single or unified idea. In fact, the whole affair was an entirely empirical and experimental procedure which somehow managed to muddle together and combine in collective exhibitions of students’ work’[2]. Former student of the Basic Course, artist and teacher Terry Marner (1955–59) agreed: ‘The earliest iteration of “Basic Design” that I experienced was something that seemed to be in a state of flux.’[3] The exercises that made sense independently, once brought together created ‘confusion and contradiction’ according to John Walker (1956–61).[4]

Artist and historian Lesley Kerman (1960–64) reflected on how this dichotomy of interpretation bore relation to the Bauhaus. As a student in the 70s, she was audience to two elderly ex-students of the Bauhaus who gave opposing accounts of studying under Oskar Schlemmer. Having had a wonderful time under his mentorship, ‘the first spoke with tears in his eyes about “Oskar”, the only teacher we could call by his first name’, while the other reported the Bauhaus was ‘full of garlic-eating hippies with dirty bare feet. Schlemmer was a monster because they made the Triadic Ballet and he took it off to Berlin and claimed it was his work’. Lesley proposed that one might also find such disparate remembrances from students of the Basic Course: ‘Some people found it blocked their creativity – others are still doing the exercises – to me it was a very exciting time that has given me a wonderful life in art.’[5]

On arrival in the department, in a similar manner to the Bauhaus, school leavers would be expected to ‘unlearn’ their more rigid approach to painting acquired at school. Gropius stated of the preliminary course, that ‘the first task was to liberate the pupil’s individuality from the dead weight of conventions and allow him to acquire that personal experience and self-taught knowledge which are the only means of realizing the natural limitations of our creative powers.’[6] On the Basic Course, they were to replace previous knowledge with an experimental, abstract way of thinking, described by Hamilton as ‘erasure’. ‘One purpose of the Basic Design course was to provide all students with a common starting point; another was to destroy any preconceptions about the nature of art that students might have acquired at primary and secondary schools.’[7] Derek Morris, a student from 1958 to 1963, explained that ‘it was quite uncomfortable in lots of ways – it tipped you on your head. It changed me forever. My thinking about art changed forever.’[8] Uncertainty, discomfort and ambiguity in the teaching and ultimately the creative outputs seemed part of the intent, and the department was considered as being one of the most progressive and advanced in the country though the significance of this may not have been appreciated at the time: John Walker only later realised that ‘we were participating in an art-educational experiment of national importance’.[9]

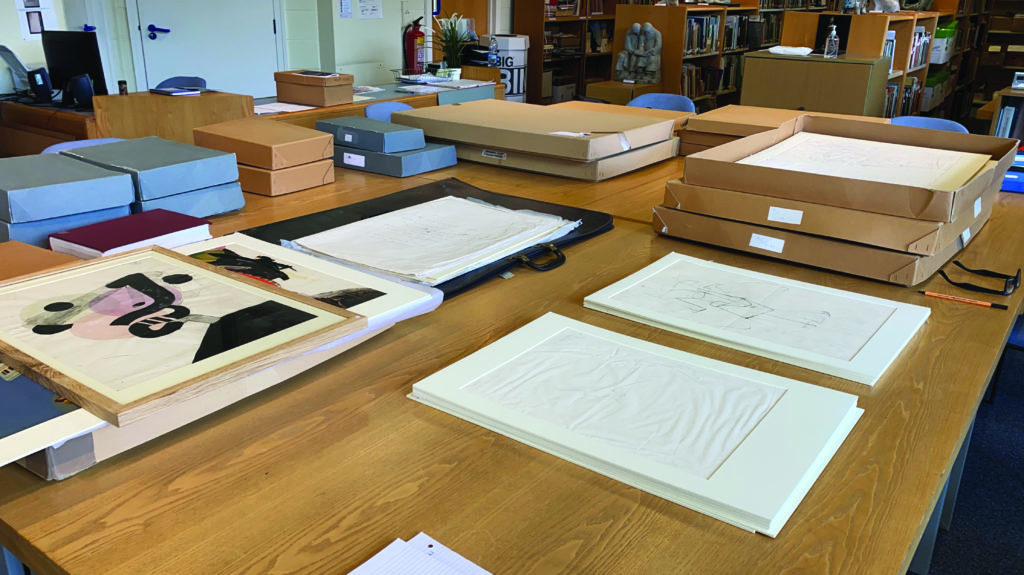

The clear relationship between the work produced by students on the Basic Course and the Bauhaus has been well-documented from many angles, and the historic background of basic design in the UK was explored and presented in the exhibition Basic Design at Tate Britain in 2013. Despite this wealth of information I was not prepared for the impact of seeing the volumes of paintings and drawings on recent visits to the Hatton Archives, Newcastle, and more so at the National Arts Education Archive (NAEA) in Yorkshire, where the unassuming yet hugely knowledgeable curators and custodians Anna Bowman and Leonard Bartle have worked with this immense portfolio of artwork, letters, essays and photographs for many years and were therefore able to bring historic threads together in their accounts and anecdotes. Being neither an artist nor an art historian, I felt underqualified to base this essay on the works themselves. The collection of photographs stored in both repositories intrigued me though and connected back to the importance of space and atmosphere in education.

[2] Victor Pasmore. Brief an Richard Yeomans. National Arts Education Archive, 1983.

[3] Terry Marner. E-Mail-Korrespondenz mit Julie Trueman, 2021.

[4] Zitiert in: Gill Hedley. A Developing Process, 2013. Abgerufen am 22. August 2021 unter

[5] Lesley Kerman. E-Mail-Korrespondenz mit Julie Trueman, 2021.

[6] Walter Gropius. The new architecture and the Bauhaus, London: Faber, 1965.

[7] John A. Walker. Learning to paint: a British art student and art school 1956–61., London, Institute of Artology, 2003.

[8] Derek Morris. Telefongespräch mit Julie Trueman, 2021.

[9] Walker 2003.

Architecturally, educationally and spiritually, the studios of the department of fine art were inherently entwined with the Basic Course serving a fundamental physical role in the exercises themselves. Hamilton set a version of the ‘positive and negative’ exercise inviting students to draw the room and the negative shape around the objects within.[10] Lesley Kerman remembers the week on ‘line’ exercises standing out for her as a ‘marvellous leap in understanding, a paradigm shift in my conception of what was possible’, going beyond the parameters of what the body could do and engaging the room itself: ‘The span of the arm, the sweep of the mark, the rhythm of the movement across the roll of paper – why stop?’[11] Similarly Pasmore described an extension of Klee’s exercise of not only taking a line for a walk but instead of stopping at the canvas, ‘why not go over the frame, round the room, out of the window and into space?’[12] Recognising this significance, former student John Kinnaird described the responses to exercises under Hamilton as sometimes being more concerned with the environment and the room itself: they would be ‘statements which involved things having happened in the room which was to do with shape making or point grouping and there wouldn’t necessarily be a sheet of something to stick on the wall. It would be a statement of what had actually happened within the room.’[13]

Still, the ability and necessity to physically engage with the architecture was also part of the Basic Course. Photographs of the studios show the walls covered from floor to ceiling with work with most surfaces used in some way including tables and often the floor itself, in ‘extraordinary sessions’ described by Rita Donagh where Pasmore would encourage big shapes to be drawn in charcoal on cheap paper that were then mounted vertically.[14] So, although the visual transparency of the Bauhaus building in Dessau was missing in King’s College, the solid walls displaying work allowed no place for hiding. In a powerful analogy, Derek Morris stated that as the work was pinned up for the Friday afternoon ‘crit’, the studio was transformed into a ‘teaching museum’.[15]

[10] Richard Hamilton. Basic Design. Interview. Northend Farm, 1982.

[11] Kerman 2021.

[12] Victor Pasmore. Interview. The Arts Club, 1984.

[13] John Kinnaird. Interview with Peter Sinclair, 1974.

[14] Cited in Richard Yeomans. The Foundation Course of Victor Pasmore and Richard Hamilton 1954–1966. Dissertation thesis, 1987, https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10007507/1/282700_vol1.pdf

[15] Morris 2021.

Out of all the studios, Room 2 holds particular historic significance (described as the ‘infamous room 2’ on a recent tour of the department) and perhaps encapsulates all of these characteristics of use. The photo shown in figure 1 was the initial prompt for this essay, with a question over what could be decoded from the semiotics of the image. In an assertive pose, Pasmore is seen standing slightly aside and somewhat disconnected from the students (perhaps reflecting this aspect of his personality), though clearly willing to take part. At the centre of the students, who seem at ease in the environment, sits Derek Carruthers holding a metal bucket on which is written ‘Room 2’. On questioning Terry Marner, who also appears in the photo, he explained that as Derek most likely set up the photo and since he was the most ‘senior’ student, then he would ‘have the bucket’. ‘The bucket was an ever-present utilitarian object in each studio. Since we painted in oils, it contained a quantity of turps and a perforated metal sheet. I suspect that it was the most convenient way of identifying who we were.’[16]

Those students showing an interest in abstract art were selected by Pasmore to study in Room 2[17] evidenced by Derek Morris who recalled Pasmore stating to him: ‘You don’t have to do life drawing anymore because the future is abstract for art.’[18] Ron Dutton, (1956–60) further described Room 2 as ‘the home of the experimentalists under the sway of Pasmore soon after he arrived’,[19] with Terry Marner adding that there was constant discussion in Room 2, each student grappling in their own personal way with the ideas that Pasmore offered when he came in to see what they were doing.[20] So while the evidence seems to be that the character came not from the room itself but ‘from what happened inside it’,[21] Lesley Kerman gives due respect to the architecture: ‘I think that the walls bore witness to how much we were learning and how we were engaging with the course.’[22]

It is clear from the descriptions by former students that the spaces for working (studios, workshops, library, etc.) contributed to the atmosphere and the feeling of being part of something ‘different’. Lesley described Basic Course students working together on tables in one large studio with the work mounted immediately onto the walls, giving a sense that ‘the work that we were doing was a collective project to which we were all contributing’. Terry Marner verified this idea of a collegiate approach that created a synergy and awareness of each other’s work between those working in close proximity. Both recognised the connection to the Bauhaus in their accounts, Terry recalling many discussions about how the issues they were dealing with related to European tradition and how this was described by Pasmore.[23] Lesley reported that Hamilton inferred a stronger, more defined link: ‘What we were doing seemed to be original – discoveries were being made every day. We certainly shared the Bauhaus idea that making good art and good design would improve the quality of life for the whole culture. We also shared with the Bauhaus the idea of culture including everything made was used or thought about – at a time when in England the word usually signified something on a higher level than most people could aspire to. Hamilton was very important in making this clear.’[24]

[16] Terry Marner. Email correspondence with Julie Trueman, 2021.

[17] Derek Carruthers. ‘Derek Carruthers (1935–2021)’. Modern British Pictures, 2020. Retrieved August 23, 2021, 2021, from https://www.modernbritishpictures.co.uk/artist/derek-carruthers/

[18] Morris 2021.

[19] Cited in Hedley 2013.

[20] Marner 2021.

[21] Morris 2021.

[22] Lesley Kerman. The memory of an art school: a response to the conference at the University of Newcastle, Victor Pasmore, Richard Hamilton: Radical Innovation in Art, Architecture and Art Education in the North East, May 2013. Devon: Little Silver Publishing Ltd, 2013.

[23] Marner 2021.

[24] Kerman 2021.

Beyond, and integrated with, the architecture, the success of the Basic Course was also dependant on the atmosphere created, largely in part due to the opposing personalities of Pasmore and Hamilton. Pasmore was described as ‘erratic, almost incoherent’ yet at the same time ‘eloquent and inspiring’[25] with a very strong personality, a man who ‘makes disciples. He’s a sort of messianic character.’[26] Hamilton, on the other hand appeared measured, thoughtful and ‘had an air of huge intelligence about him – quite an extraordinary personality.’[27] As serious practicing artists, each with their own studio, they both however, brought a palpable seriousness to the Basic Course, described by Mary Webb (1958–63) as giving a ‘head of steam to the place.’[28]

At the same time, Hamilton exerted a more unconventional influence through his departure from traditional fashion (often dressed in Levi’s jeans and shirts) and music, where he was renowned for importing the latest American Motown music. This encouraged a more off-beat mood to the department. In a vivid recollection by Andrew Morley (1965–69) of his first highly dramatized encounter with Hamilton, he stated, ‘We were smitten! These people were TRENDY! SO cool.’[29] Visiting established artists and their occasionally eccentric behaviour also contributed to the atmosphere which gave the department and its students a sense of ‘being in the forefront of creative activity.’[30] And just as at the Bauhaus, where Schlemmer in particular had recognised that ‘play’ through recreational activities such as costume parties, poetry and music was a crucial element for creativity, this was also a vital part of student life for those studying in Newcastle. Parties, particularly those hosted by Hamilton, or lunchtime trips to the Majestic Ballroom were an integral part of life in the department. In the 1958 student film by Michael Dawson, a unique glimpse is given into how this contributed to an enhanced atmosphere on the Basic Course.[31] Dancing on the roof, students and staff (Pasmore is clearly visible) are relaxed yet dynamic, with more scripted scenes in the life room illustrating that work and play were important contributors to the overall experience. Having nothing else to compare it to at the time was like being ‘in a bubble to some extent’ recalled Stephen Buckley (1962–67).[32]

It is unclear whether Hamilton and Pasmore drew from the Bauhaus model to develop this creative learning environment because it was seen as modern and different or if they simply believed at that time (intentionally or otherwise) that it was essential to improve their teaching and the student experience. Whichever principles of the Bauhaus pedagogy had ultimately migrated to Newcastle, Gropius’s idea of an atmosphere seemed to be firmly established with students having a sound awareness, taking it into their own teaching practice later in life: Lesley Kerman described this as ‘making a “climate”’ which, she added, ‘there most certainly was at Newcastle!’[33]

[25] Kerman 2021.

[26] Kerman 2013.

[27] William Coldstream. Interview with Peter Sinclair, 1974.

[28] Morris 2021.

[29] Mary Webb. Phone conversation with Julie Trueman, 2021.

[30] Cited in Hedley 2013.

[31] Yeomans 1987.

[32] Michael Dawson. Student Film, 1958; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b8EPZcYUkb0

[33] Stephen Buckley. Phone conversation with Julie Trueman, 2021.

Reflecting on the nature of studio life and returning to more recent events, the question arises, how can atmosphere be created or experienced when there is no longer a building within which to generate it? How can we teach interior design when the interior only exists within the personal confines of a screen? Online delivery during the pandemic raised this question to the forefront.

Returning full circle to the Bauhaus, I entered into a unique collaboration with the research academy to evaluate student engagement during online delivery of the academy’s Vorkurs module. The aim was to encourage ‘anticipation over ambivalence’ and to question whether the legacy and credibility of an iconic institution could be translated effectively and with the same success, without physically occupying the Bauhaus building in Dessau by creating an equivalent atmosphere online. This demanded new ways of presenting, of ‘teasing’ students and of evaluating. Understanding student expectations and perceptions was key, and the most valuable data collected was by sensory ethnographic methods using video stimulated recall, where recordings of online workshops prompted recall and interpretation of student behaviours and emotions.

These two-way discussions, just as with the conversations relayed here with former students of King’s College, were more genuine and responsive than static one-way questionnaires and allowed us to rapidly respond and react, interjecting with interim workshops and amendments to module delivery style and programming, injecting aspects of our own personality with nudges and prompts promoting motivation and commitment. Despite the successes gained, the sense of isolation and separation imposed by the lockdown was compounded by the absence of the physical building in Dessau and its digital replacement. This ultimately generated a nostalgic sense of loss.

Post-lockdown, on a recent visit to the department of fine art in Newcastle in September 2021, I bore witness to the impact of the King’s College building. Although it was the summer break, and empty studios were devoid of students and work, it was easy to picture the vibrancy of former times, when the Bauhaus-inspired exercises would smother the walls from floor to ceiling. The photo capturing Matt Rugg climbing on to the sink to mount the paintings and drawings ever higher had transitioned into the present, and I was standing in Room 2 faced with bare walls. But this is the nature of the cycle of education where our environments shift between ‘teaching museums’ and empty spaces. It doesn’t mean that history has faded but the historic images captured, coupled with the oral histories of students who experienced this building and the atmosphere generated within, remind us that there is more depth and explanation to them than what we see before our eyes.

is a senior academic and researcher at Northumbria University, UK. With a hybrid background of medicine (1993) and interior design (2006), her research currently focuses on pedagogy and proxemics for learning. She has co-ran workshops as part of the Open Studio Programme at the Bauhaus in Dessau, Germany, leading to a subsequent collaboration with the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation Academy.