Hajo Rose and the Nieuwe Kunstschool Amsterdam

After studying at the Bauhaus in Dessau and Berlin from 1930 to 1933, Hajo Rose (1910–1989) moved to Amsterdam in April 1934. There, he and the Belgian photographer Paul Guermonprez jointly set up the advertising agency co-op2. Based on the available evidence, it is impossible to say whether Rose considered emigrating or whether he “first wished to bide his time in a neighbouring country and see how the situation developed in Germany”.[1] Given his political and artistic views and coming as he did from the Bauhaus, he would have had no opportunities in Germany without adapting. Despite its owners’ idealism and hard work, the advertising agency foundered after just a few months. As a foreigner, Rose found it especially difficult to make a living, particularly since the Netherlands too was affected by the Great Depression. Help came from the former Bauhausler and artist Paul Citroen. Rose was appointed as a lecturer of advertising graphics, typography and photography at the private Nieuwe Kunstschool in Amsterdam directed by Citroen. Starting at the age of just 24, over the next five years (1934–1939) Rose taught the ideas and methods of the Bauhaus in subjects such as advertising, colour theory or calligraphy. He offered a preliminary course, but no photography course. Rose based his teaching on his own experiences, which he had made at the Bauhaus.

[1] Ulrike Staroste (ed.). Hajo Rose. Bauhaus Foto Typo. Berlin: Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin, Museum für Gestaltung, 2010, p. 25.

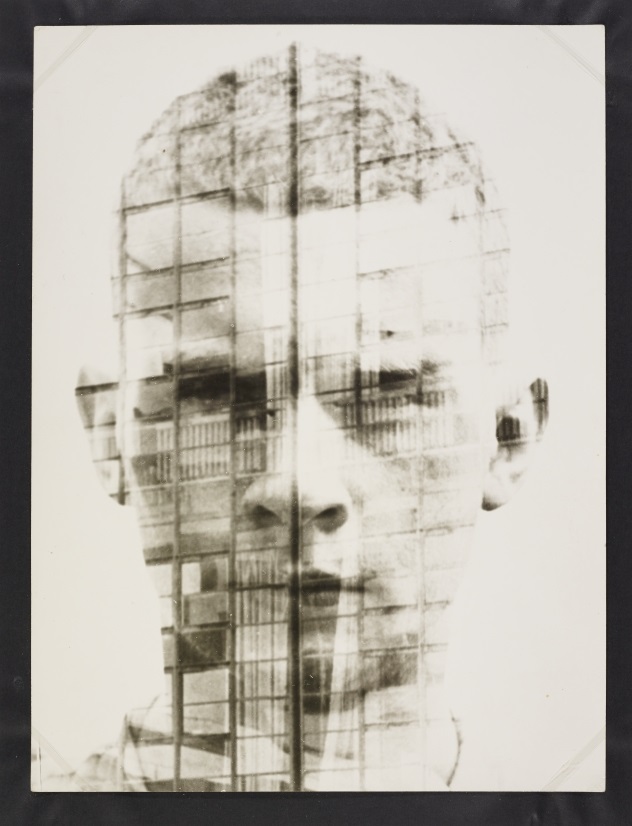

Let us therefore look back at his training. In the summer semester of 1930 at the Bauhaus, Hajo Rose first completed the preliminary course under Josef Albers and attended classes with Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee and Joost Schmidt. Following basic training in the first semester, Rose studied for two years (until mid-1932) in Joost Schmidt’s advertising, typography and printing workshop. At the same time, he attended photography classes taught by Walter Peterhans.

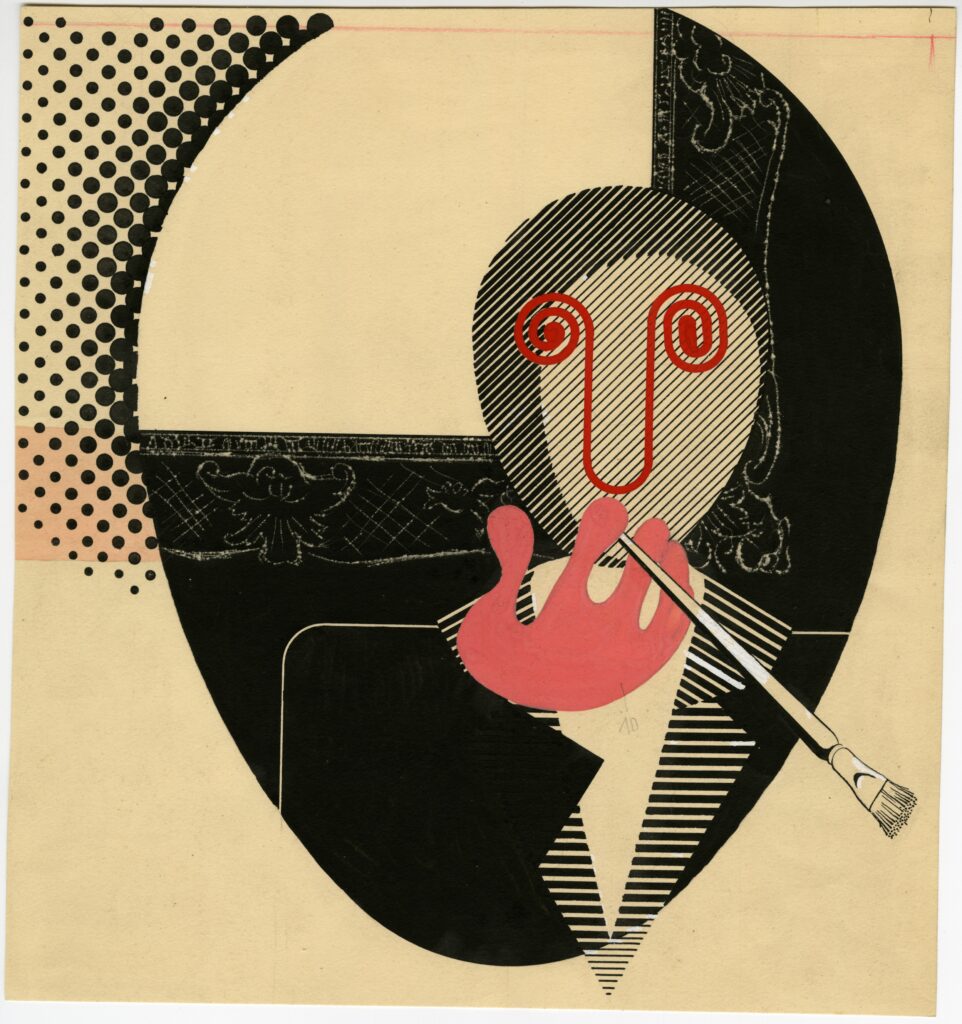

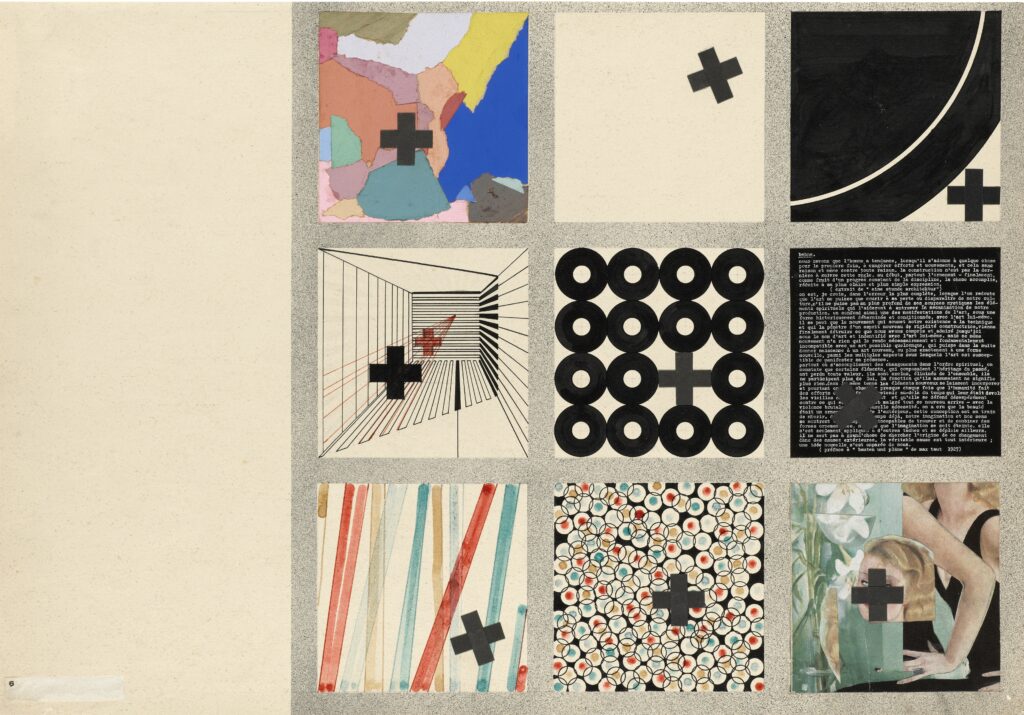

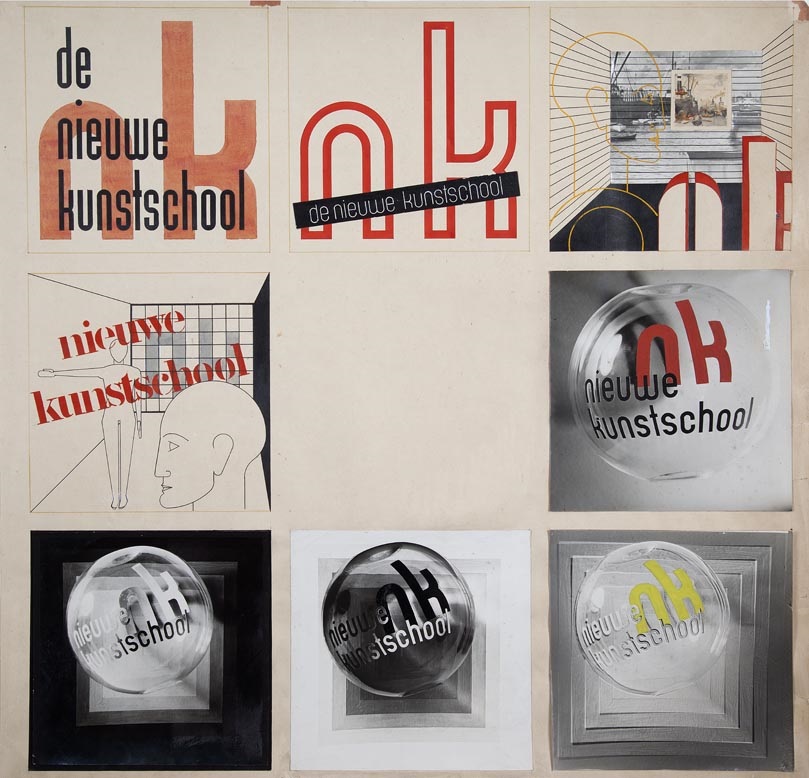

Schmidt’s classes at the Bauhaus Dessau focused on two areas: Firstly, on investigating the relationship between the body and space and secondly, on advertising, typography and lettering. On Schmidt’s courses, students were provided with a solid foundation, broadly consistent with the Bauhaus’s teaching. In his class, a typical task, the complexity of which increased by degrees, involved design exercises based on a standardised pattern of three squares by three, into which students would insert nine variations on a given theme. Hajo Rose is known to have completed such exercises. “The intention was to train creative thought, thinking in terms of alternatives and, in addition, to show the students that a design task can have more than one solution.”[2] One contrast exercise by Hajo Rose shows the cross symbol as a collage, as a perspective drawing, rendered using letters, etc., thus utilising formal and thematic contrasts. (Fig.)

[2] Rainer K. Wick. Bauhaus-Pädagogik. Köln: DuMont, 1994, p. 308.

Hajo Rose continued to study at the Bauhaus even after it moved to Berlin. He was awarded the Bauhaus Diploma no. 112, issued by the advertising workshop, on 1 April 1933. Rose thus exemplifies the depth and influence of a Bauhaus education as an essential condition for the formation of an autonomous and lasting artistic-aesthetic design vocabulary that in typography and photography alternates between the New Vision, Surrealism and New Objectivity.

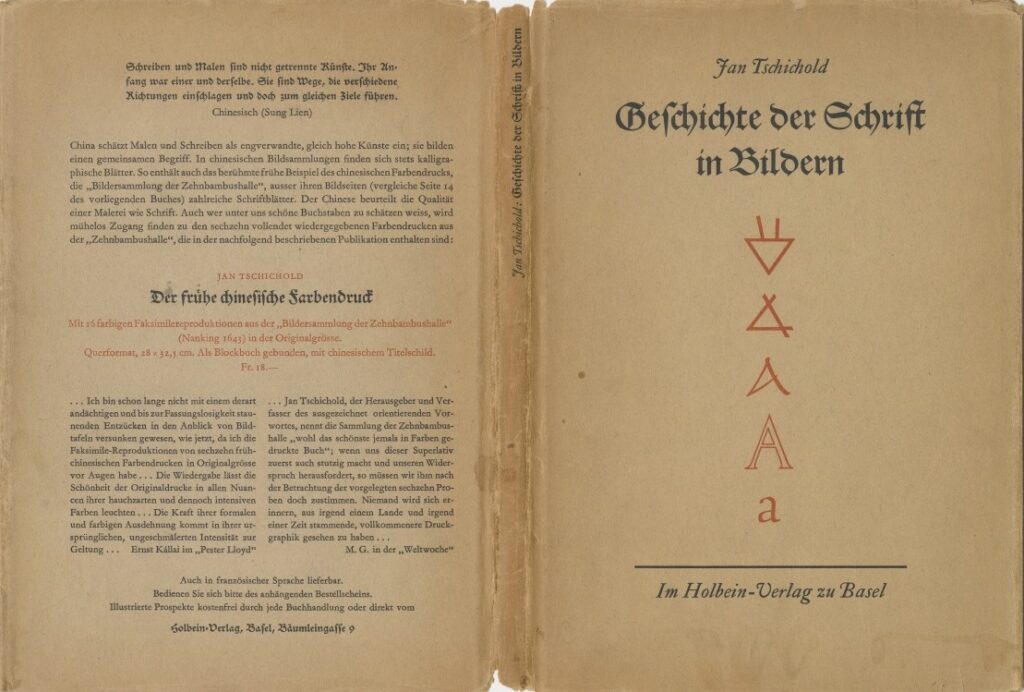

Evidently, a Bauhaus education and a certain talent as a teacher were a good basis for work as a lecturer in Amsterdam. Just like his teacher Joost Schmidt, Hajo Rose was popular with his students. He taught advertising (including typography, photomontage, poster art, publicity and brochures), colour theory and drawing. According to Jan Bons, one of his students, Rose was the only teacher to use a textbook for classes, namely Jan Tschichold’s Typographische Gestaltung (1935), published by Duwaer in Dutch translation in 1938.[3] As correspondence shows, Rose thought highly of Tschichold, who made avantgarde concepts in typography broadly acceptable and, tellingly, fled to Switzerland when the National Socialists came to power in 1933. He became a teacher at a vocational school in Basel, where he worked until 1941.

[3] Cf. Kurt Löb. Paul Citroen en het Bauhaus. Utrecht, Antwerpen: Bruna, 1974, p. 70.

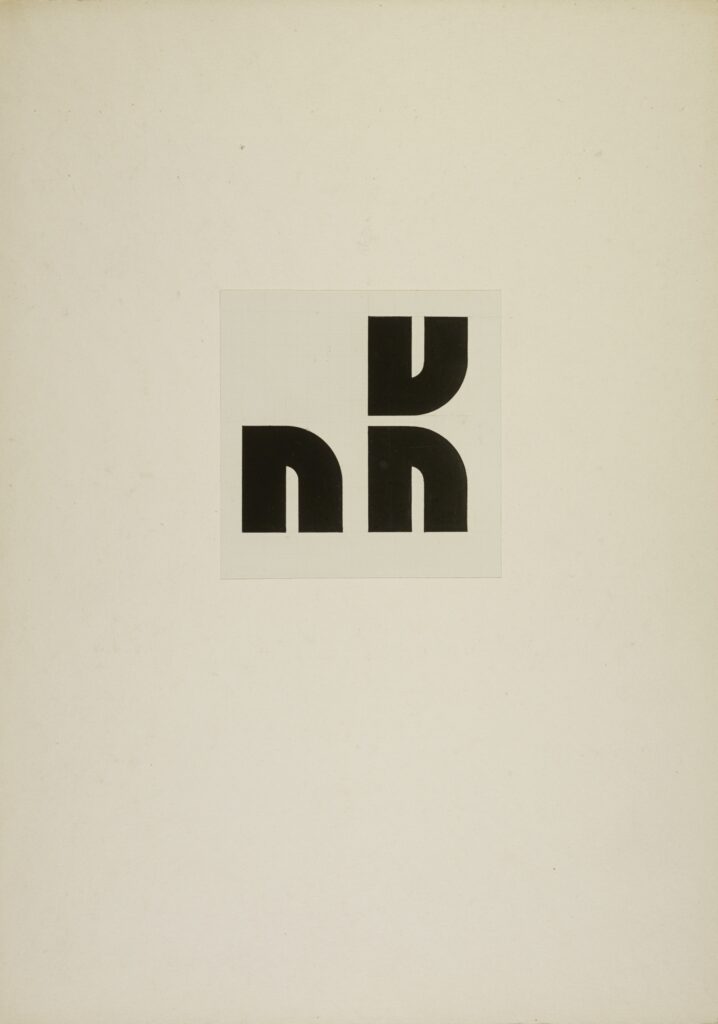

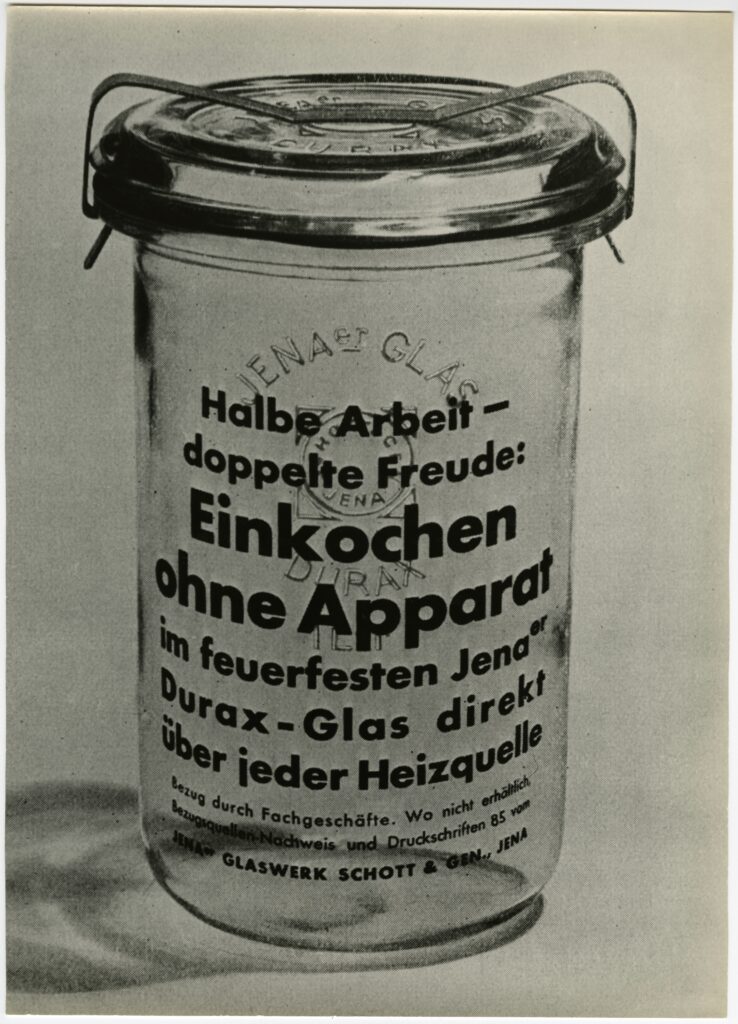

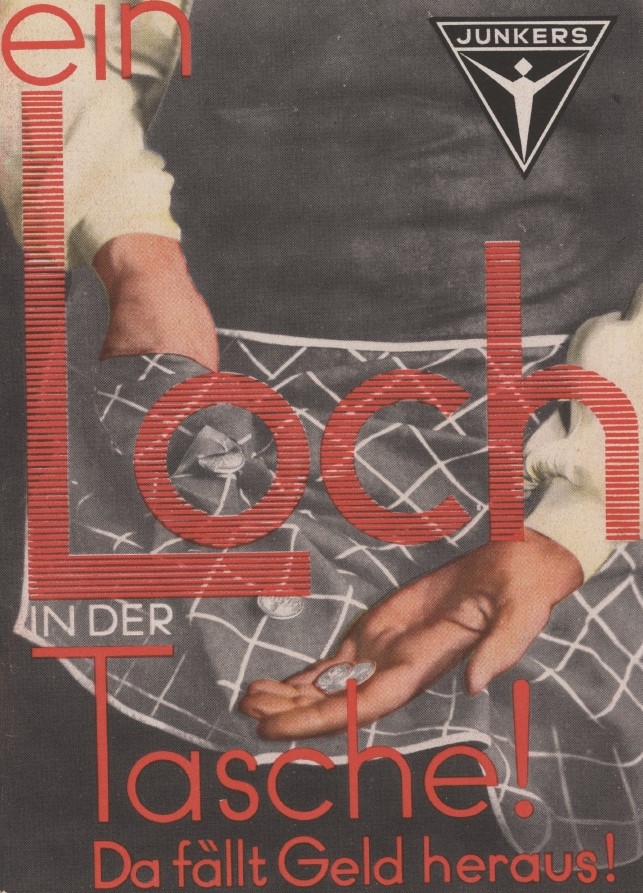

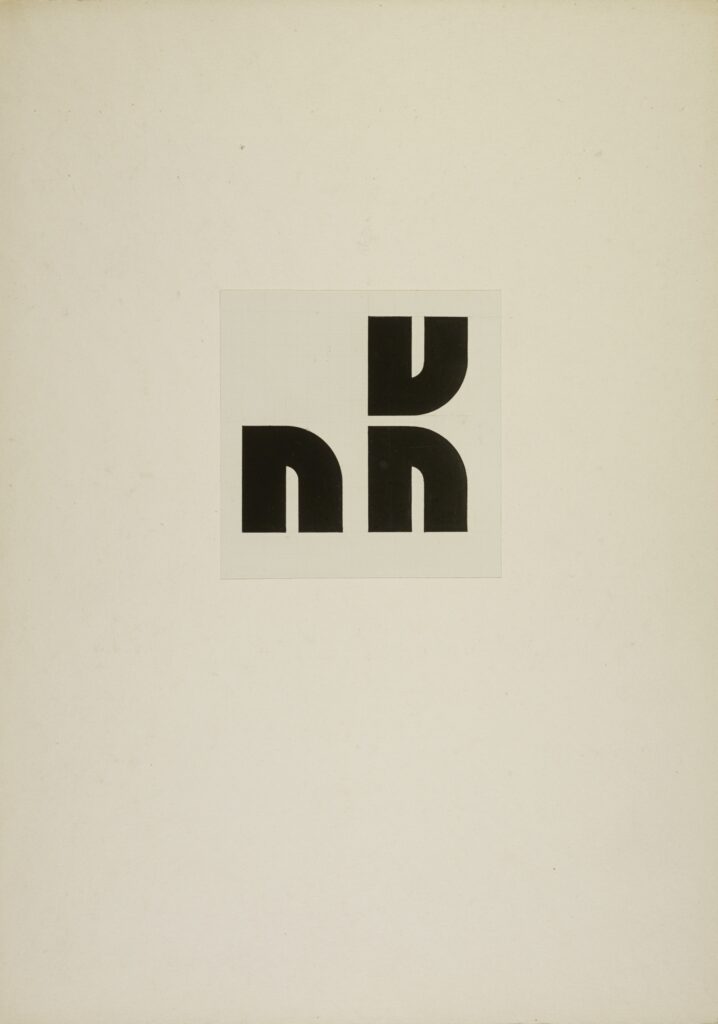

Hajo Rose designed all the printed matter the Nieuwe Kunstschool required, such as brochures, letter paper, invitations to parties, etc. Of these, one interesting example is the design Beispiel für eine Lektion, Vorstudien für ein Plakat für die Nieuwe Kunstschool (Example for a lesson, preliminary studies for a poster for the Nieuwe Kunstschool). In terms of its composition and use of various contrasts, this is highly reminiscent of the exercises from Joost Schmidt’s class. (Fig.) Rose also utilised this pattern of three squares by three in his lessons, as is shown by an example for a class titled techniecken en stijlen (Techniques and styles).

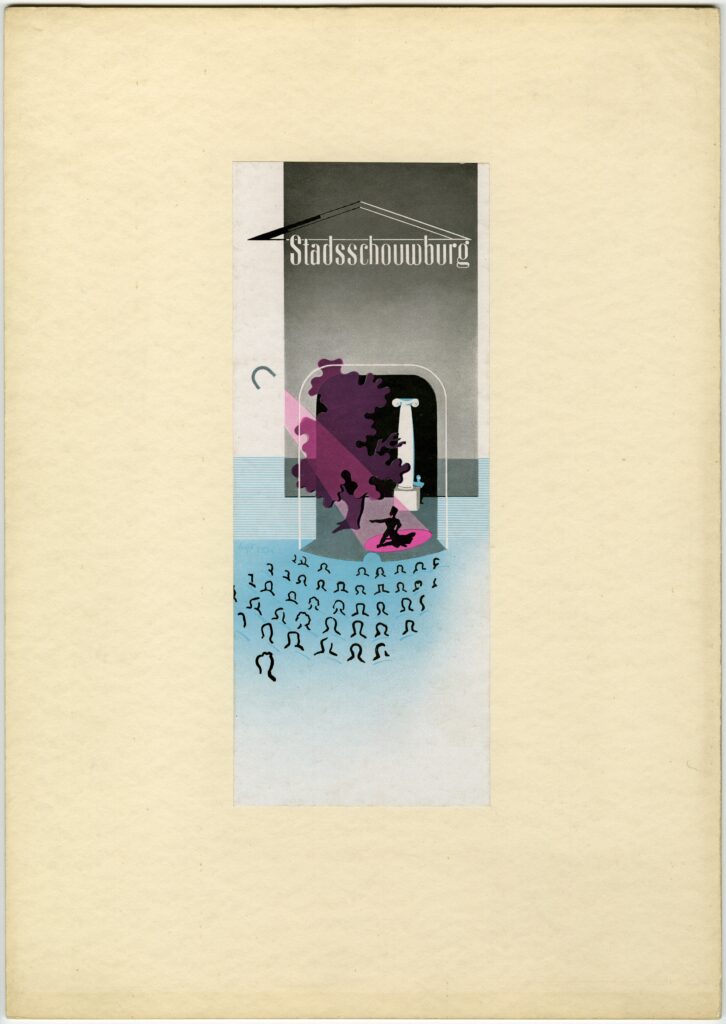

In parallel with his work as a lecturer, Hajo Rose ran an advertising agency (until 1941) and worked as a freelance photographer, exhibition designer and set designer. His versatility and various talents were also expressed in work for the printer and publisher Frans Duwaer, for whom he designed calendars and invoice forms. Rose knew Duwaer from collaborations at the Nieuwe Kunstschool, because Duwaer produced all the printed matter for the school. Rose received commissions from both established companies and institutions such as the medical-therapeutic institute Inrichting Fransman and from refugees such as the Hungarian photographer Eva Besnyö, who likewise taught at the Nieuwe Kunstschool. Rose was also in touch with other Bauhauslers in Amsterdam and with the Dutchmen Mart Stam and Johan Niegeman. In 1939, Stam was appointed director of the Instituut voor Kunstnijverheidsonderwijs, an arts and crafts school in Amsterdam. Niegeman was head of the interior design department at the same school.

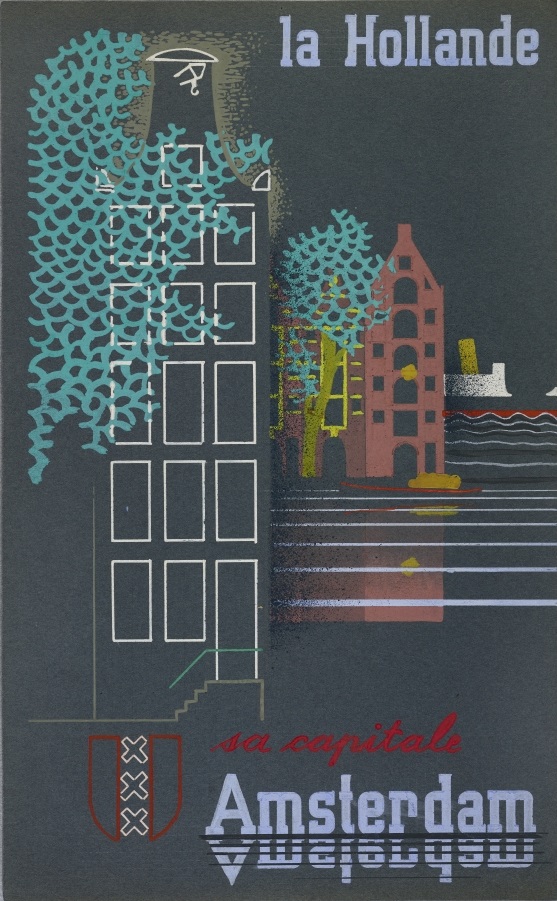

Rose represented the Netherlands at the 1937 World Exposition in Paris and won a gold medal for the poster Amsterdam. (Fig.) In 1939, he designed the exhibition Der Zug for the Netherlands State Railways and in 1941, the trade fair stand for several food producers at the Utrecht Spring Fair. In 1941, he worked as a film architect on the UFA-produced film Rembrandt.

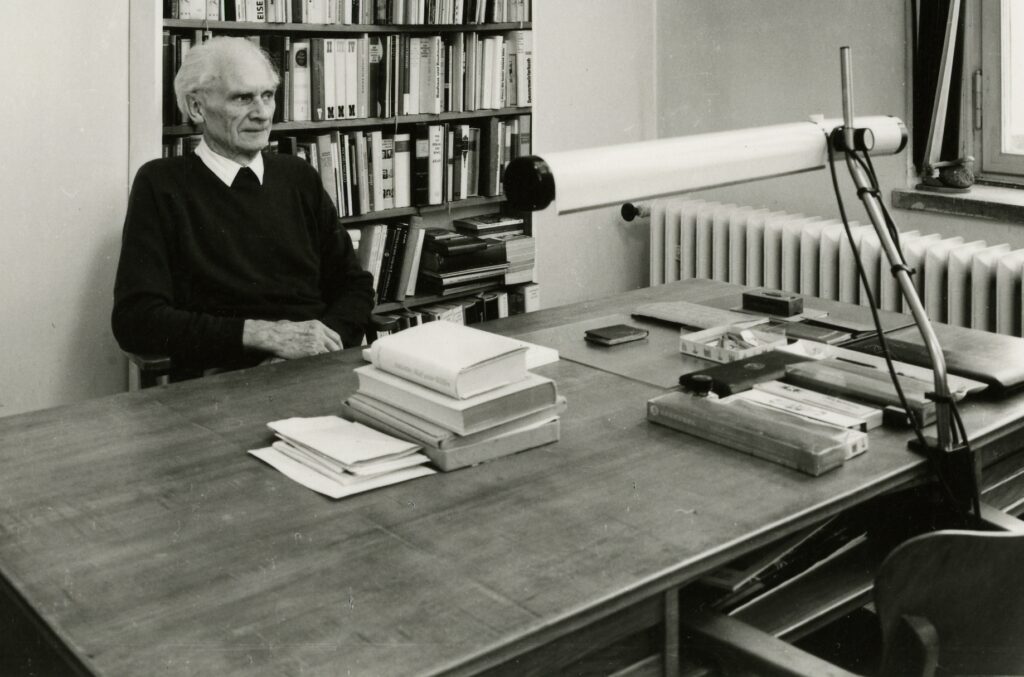

In 1942, as an émigré in the Netherlands, Rose was forcibly drafted into military service. After the war, he found himself in captivity as a prisoner of first the French, then the Americans. He first returned to Germany in 1948. After much deliberation, Hajo Rose finally moved to Dresden, taking up an invitation from the architect Mart Stam, formerly a visiting lecturer at the Bauhaus. In Dresden, Stam was working on reviving the Bauhaus idea, and with the designer Marianne Brandt, a small Bauhaus cell formed. Rose was able to resume his career in the GDR. From 1949 to 1953, he taught at Dresden University of Fine Arts, lecturing in advertising art and typography. Following the closure of his department in Dresden in 1953, Rose relocated to the Fachschule für angewandte Kunst Leipzig (School of Applied Art Leipzig) and taught there over the following five years. Because the school administration repeatedly criticised his Bauhaus-influenced teaching methods, he eventually left the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED), thus providing grounds for his dismissal. As a result, he was banned from teaching in the GDR. Over the following years, Rose was active as a freelancer. His work was shown in numerous exhibitions, especially from the 1970s onwards. Hajo Rose died in Leipzig on 10 September 1989.

(DPhil.) has been working at the Depot/Archive of the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation since October 2011. Prior to that, she was employed as an art historian at the Bildarchiv Foto Marburg, the Deutsche Fotothek Dresden, the Kunstfonds des Freistaates Sachsen and at the business consultancy startext in Bonn, among others. Her areas of expertise include reviewing art collections, collaborating on projects, and developing and customising database systems for museums and archives. In keeping with her art history dissertation on the topic Der Bildband “Dresden – eine Kamera klagt an” von Richard Peter senior. Teil der Erinnerungskultur Dresdens, her interests focus on the history of photography and art in the GDR.