From Theory to Practice. Open Form in Architecture

It is 1959. The last of the International Congresses of Modern Architecture (CIAM) is taking place in Otterlo, Netherlands, and the young Polish architect Oskar Hansen takes the podium. He will give a lecture in which he sharply criticizes the current architectural situation and the “Pope of Modernism” – Le Corbusier – who is sitting in the audience. He does not yet know that his listeners will reward him with thunderous applause and that the theory he presents will become one of many supports for a new generation of architects that will eventually lead to the downfall of the supremacy of the International Style.

In the Netherlands, Hansen presented the concept of the Open Form. He believed that architecture should be the framework for life. He wanted an architecture that was not universal but an architecture that was adapted to a particular user, capable of changes that corresponded to changes in human life.

Hansen’s ideas were great, but he often developed visions that were so utopian that they were incomprehensible to the Polish investor community at the time. That is why he needed a co-worker who could bring his imagination back down to earth. His closest partner, both at work and in private life, was Zofia Garlińska-Hansen. They met while studying architecture and got married in 1950. Zofia Garlińska was an architect and received her education from leading exponents of Polish modernism. Immediately after the end of the Second World War, she had found a job at the Office of Reconstruction of the Capital, where she worked on the reconstruction of the Warsaw monuments.

Shortly thereafter, she began her studies at the Faculty of Architecture of the Warsaw University of Technology in the class of Romuald Gutt. She stood out from the other students and was offered a job at the Warsaw Housing Cooperative, an organisation of architects with left-wing, modernist views. There, for many years, she worked together with her husband. It should be noted that she was a full member of the team and that her contribution to the projects corresponded to that of Oskar Hansen. Although she often questioned her abilities, her husband always mentioned her as one of their projects’ authors. According to family lore, she was primarily responsible for translating Hansen’s often incomprehensible ideas onto paper and then into practice. At the same time, with her architectural imagination, she demonstrated an awareness of the realities prevailing in Poland and was able to adapt the designs accordingly.

Sometimes, when Hansen did not receive commissions because of his political views – he was openly opposed to the social-realist doctrine – she took care of securing them jobs. Although it is difficult to determine who was responsible for what part of the realization of plans, one thing is certain: architecturally, there would be no Oskar Hansen without Zofia Garlińska-Hansen and Zofia Garlińska-Hansen without Oskar Hansen. They were a perfectly complementary couple.

The Hansens did not want the Open Form theory to remain just on paper. They wanted to make it happen. For them, the creation of exhibition pavilions was a special experiment. They designed pavilions for the International Fair in Izmir, Turkey, in 1955 (Oskar Hansen, Lech Tomaszewski) and in 1959 in São Paulo, Brazil (Zofia Hansen, Oskar Hansen, Lech Tomaszewski). Both constructions had tent roofs that swayed in the wind and changed shape constantly under its influence – an example of the Open Form. Especially in São Paulo, they exuded an impression of ephemerality and fragility, especially since the Polish pavilion was adjacent to a concrete monolith with a monumental awning designed by Oskar Niemeyer. Open Form, Closed Form.

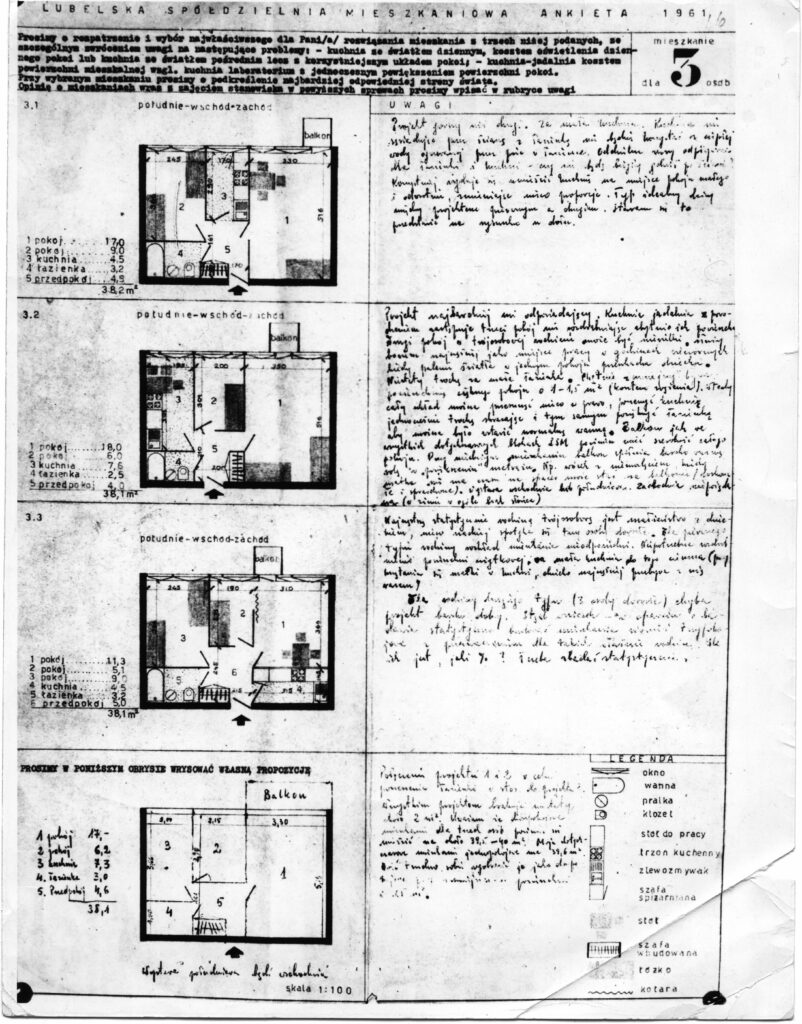

The first major contract with which the Hansens were able to achieve the Open Form was the design for several buildings in the Rakowiec residential estate in Warsaw. They didn’t want to build an ordinary block of flats in which all the apartments looked the same. They wanted every user to have a room that was designed for them. In this context, they conducted dozens of interviews and provided questionnaires with future residents. Thus, they created different types of housing, e. g., for the elderly, families, couples without children and even for a widower raising a small child and living with his mother-in-law.[1] Unfortunately, the reality of centrally controlled Polish housing meant that apartments were randomly allocated to users. Probably only a few people got what they expected.

[1] Filip Springer, Zaczyn. O Zofii i Oskarze Hansenach, Warszawa: Karakter, 2022, p. 105.

However, Zofia and Oskar Hansen did not give up on their ideals. Word spread that they had an unusual perception of residential architecture. In 1961, the board of the Lublin Housing Cooperative commissioned them to plan an entire residential estate which soon received the name Juliusz Słowacki. Again, they conducted surveys and even encouraged future residents to design their own homes. However, most of them refused to do so. The Hansens developed a vision of individuality, e. g., through the random arrangement of the balconies. Also, they gave residents the freedom to make future changes: all walls inside the apartments were non-bearing walls and could be taken out if necessary, and even two apartments could be connected. They did not want long monotonous blocks to drag on endlessly, instead they gave them a meandering shape.

They also took into account the natural uneven topography of the terrain and designed some buildings higher than others. They reserved the inner part of the settlement for pedestrians; it was not possible to get there by car. They filled the space with avant-garde playgrounds (with walls, pipes and concrete profiles in different colours) and the Open Form Theater, a space shaped like an amphitheatre that could be freely used by the local community. Everything looked good, but when the first tenants moved into the apartments, there was dissatisfaction. The hilly landscape did not suit them and the playgrounds were associated with bomb shelters. However, the worst were the flats themselves. There were no right angles but thin walls, ceilings on different levels or poorly routed ventilation systems. The Hansens were criticized.

However, the question is, was it really their fault that the residents were not happy with their apartments? Or was it the fault of the contractor who tried to do everything with the least effort? Those who were satisfied had no doubt that the poor workmanship was responsible for the inglorious reputation of the Słowacki residential estate. One resident reported how he first lived with his wife and two children in a two-room apartment. After a few years, they bought the adjoining one-room apartment and expanded the area. After the children left and he separated from his wife, they decided to rebuild the wall and now they have two separate flats. That is Open Form in practice.

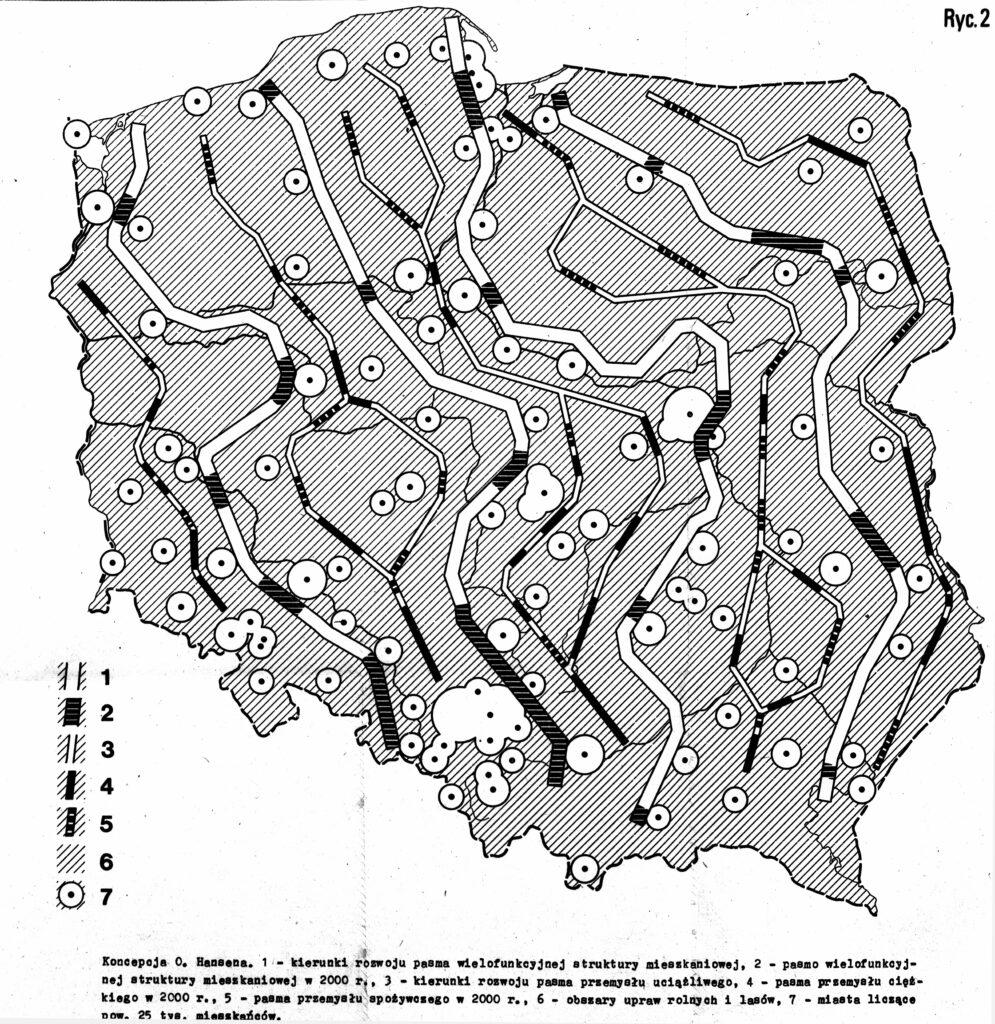

One of the biggest projects of Oskar and Zofia Hansen, in which they wanted to realise the idea of the Open Form, was the Linear Continuous System which in Polish is abbreviated as LSC. It was not the design of a single house, but an urban project that reached across the whole of Poland. The LSC was to break with the familiar form of the central city in favour of cities that develop linearly. It included the construction of four stripes of buildings running from north to south. Natural, agricultural and industrial zones were to be located in between. In this way, every resident could enjoy the view of a forest or lake and, at the same time, get to work in less than half an hour.

It was an idea that turned out to be original and utopian but also unrealisable. However, the Hansens managed to implement at least part of the LSC. In 1963, they began work on the Przyczółek Grochowski residential estate in Warsaw, in which they applied their theories. They designed 23 blocks connected by galleries, resulting in a monumental building that was 1.5 km long. The galleries were supposed to serve as a meeting place for neighbours, allow for a smooth transition between different parts of the estate or facilitate the delivery of shopping to the apartments. Oskar Hansen called it “social spacetime”. However, as in Lublin, the realised idea did not find public acceptance. The galleries proved to be one of the biggest disadvantages of the settlement. Residents complained about persistent noise, passers-by who looked in at other people’s windows, cold and frequent break-ins (from the gallery it was easy to enter the apartment through the kitchen window). And instead of improving communication, they created a labyrinth hard to navigate. Here, too, the architects failed to meet the demands of the dwellers, and the complaints about the galleries were not the only ones.

Years later, Zofia Hansen admitted that she and her husband had made mistakes in the preparation of the estate. In a conversation with Filip Springer, the author of the Hansens’ biography, she said: “How many people we have made miserable there, a catastrophe!”[2] However, it is worth mentioning that once again the reality of Polish architecture during the period of the People’s Republic of Poland contributed significantly to the negative perception of the estate. The builders changed the Hansens’ plans without their knowledge. Instead of hanging the galleries at some distance from the facades, they fixed them to the facade. They lowered the ceilings, did not built in sound-absorbing surfaces and did not apply colour systems to facilitate orientation in the settlement area.

[2] Ibd, p. 9.

The Hansens did not seem to have succeeded in the realisation of the Open Form. They created interesting projects, but they did not satisfy their users. The question is whether this was really the architects’ fault. Zofia and Oskar Hansen had to work in difficult times to develop new ideas. Both the financial and social problems caused by the communist system were not conducive to the introduction of avant-garde solutions on a large scale. However, the Hansens recognised that it was the architect’s job to shape society rather than to be influenced by its negative way of thinking.[3] Today, more and more residents of Rakowiec, Słowacki or the Przyczółek Grochowski appreciate the environment in which they live. Some even say proudly that they “live at the Hansens”. Maybe the Open Form was not a complete failure after all.

[3] Oskar Hansen: ‘People came to the Przyczółek with glasses on and they got something different than they expected. They were led out of the way because, unfortunately, their dreams did not come true. Does this mean, however, that an architect should not propose something better than what a man is used to? This is the basic question. This is primarily a moral question’. Oskar Hansen. „Na zakończenie. O „humanizacji”, a w zasadzie o przywróceniu przestrzeni Przyczółka Grochowskiego”, in Jola Gola (ed.). Oskar Hansen, Ku Formie Otwartej, Warszawa: Revolver, 2005, p. 101.

(* 1997) is an art historian, associated with the Jagiellonian University in Kraków, where she will complete her master’s degree in 2023. Her research interests focus on the materiality of modernist architecture, especially surfaces made of raw concrete or covered with fine plaster. In July and August 2022, she was an intern at the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation.