Learning to teach. Indigenous epistemologies and Lena Meyer-Bergner in Mexico

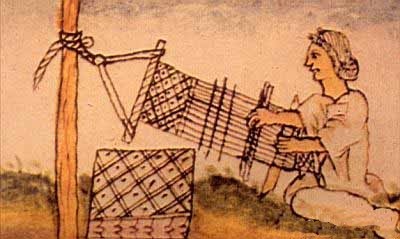

The Otomís from the Mezquital Valley define themselves as hñähñü from hñä (to speak) and hñü (nasal); meaning those who speak the nasal language or those who speak two languages.[1] Since ancestral times, this community has produced, among others, woolen rugs, maguey fiber ayates and textiles made on backstrap looms. These crafts, as carriers of “indigenous epistemologies” beyond “artisanal epistemologies,”[2] should be seen as a body of knowledge that allows entry into other worlds of existence – a position that Lena Meyer-Bergner might have shared.

[1] SIC MEXICO, Sistema de Información cultural. http://sic.gob.mx

[2] I distance myself from the idea of a “craft epistemology” as it reinforces the Eurocentric view of the idea of craftsmanship as a skilled work which does not involve many intellectual capacities. The word craftsman is rooted in a European system of people with a special know-how who are not seen as carriers of scientific knowledge. Therefore, I am closer to the concept of “indigenous epistemologies.”

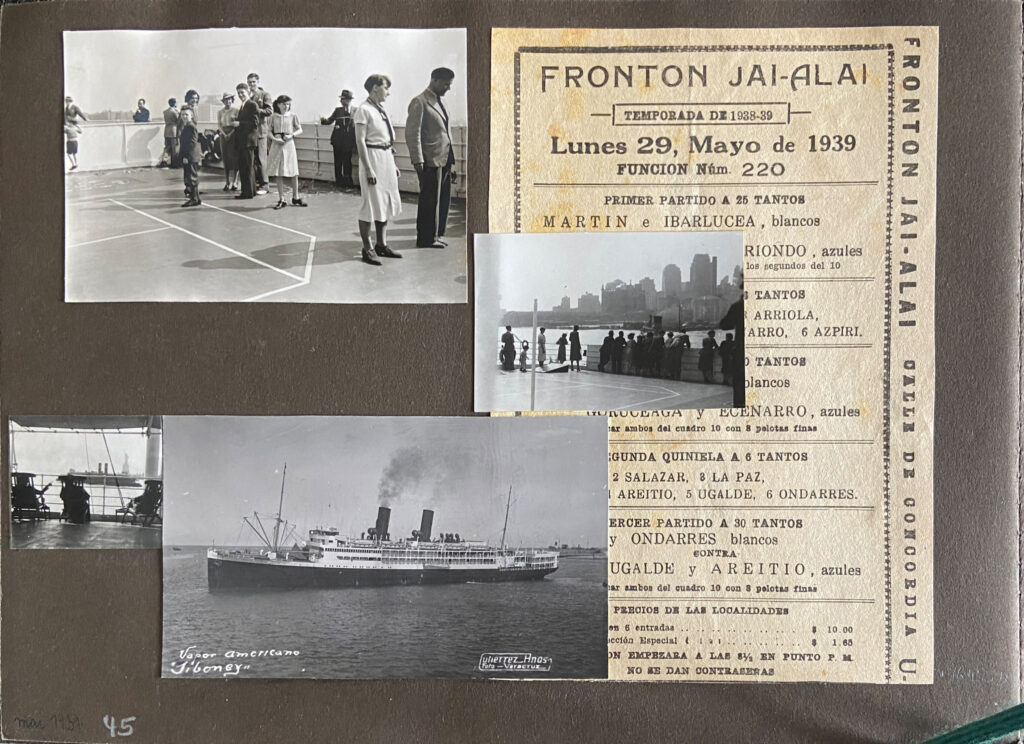

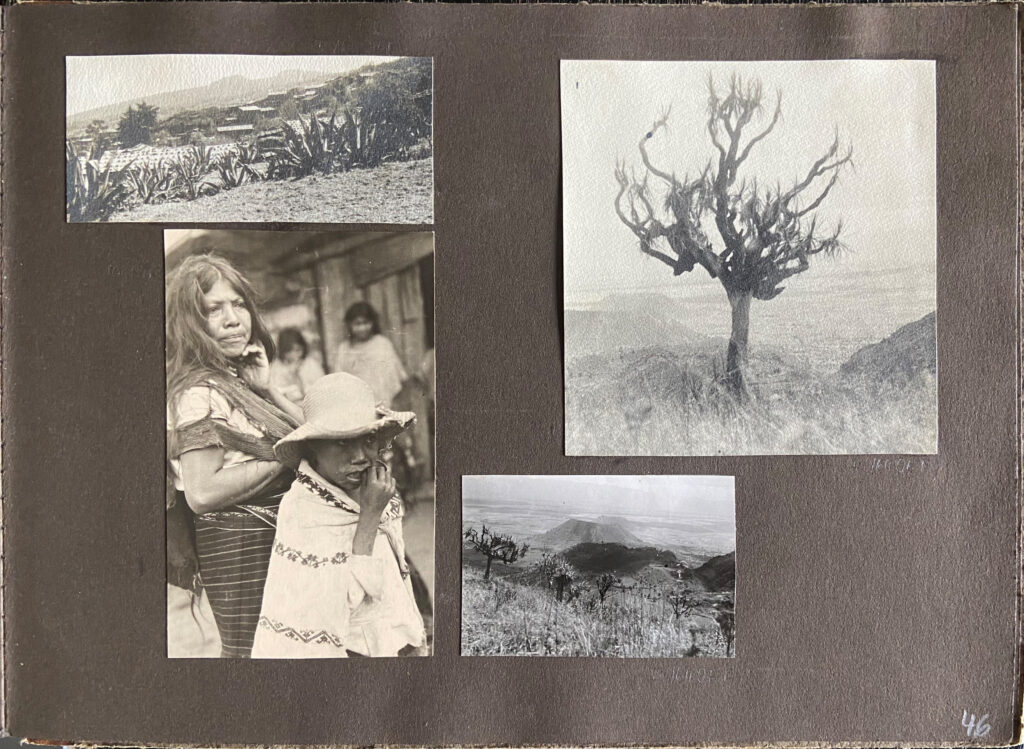

Although, so far, there is no clear evidence of the existence of a curriculum for the Otomí weavers, there are hints in Meyer-Bergner’s writings, drawings and textile designs that may help to collect her ideas or a possible concept for the realization of such an educational undertaking. Her own travels recorded in the family’s travel book show her (their) profound interest to know native cultures in Mexico. Here we can see the fascination and admiration for the pre-Columbian cultures that still exist today.

This fascination for pre-Columbian cultures has colonial roots. Since the 18th century, Europeans felt attracted to the “nature” of indigenous or “primitive” societies as a response to their own contemporary dilemmas, perhaps prompted by the movement of the Enlightenment. The attitude towards these communities changed constantly. In the 20th century, a more attentive position with respect to the values of “primitive” people and their “art” influenced the arts and sciences of the epoch. The word primitive was commonly used to define native cultures and may have been a way of perpetuating hierarchies of knowledge.

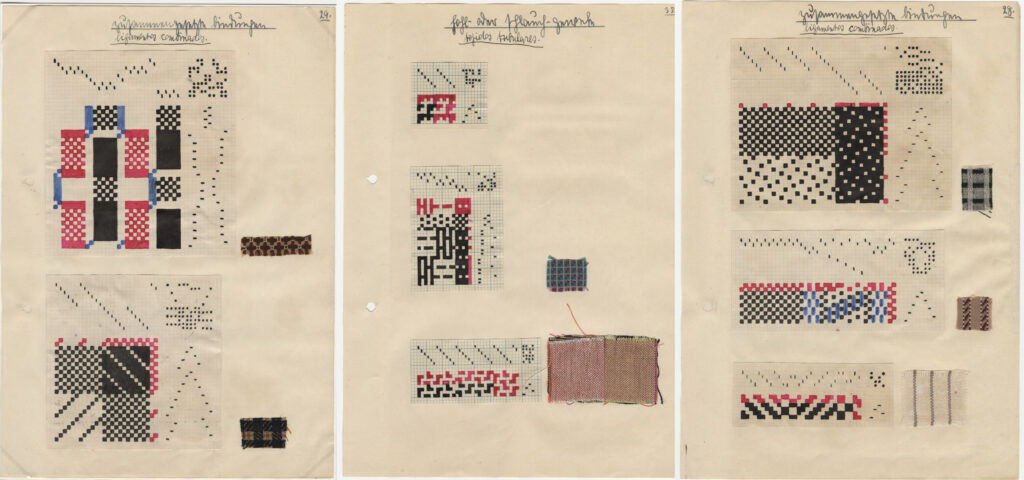

I propose to have a look at Meyer-Bergner’s attempt of reinterpretation and translation of her artistic vocabulary into Spanish. Her notes from the weaving class of Gunta Stölzl during her studies at the Bauhaus Dessau can be seen next to certain terms used in weaving on some of her texts. This shows her determination of using Bauhaus methods even beyond the school; one could say she made this translation directly on her former notes to use the same visual material she had gathered. Some of them were still present in her teaching methods. After obtaining her diploma at the Bauhaus, she went on to work in a leading position at the East Prussian Hand-Weaving Mill in Königsberg (today’s Kaliningrad), a non-profit institution that assisted impoverished sharecropper families, who could add to their income by handcrafting textiles.[3]

[3] Patrick Rössler, Elizabeth Otto. Frauen am Bauhaus: Wegweisende Künstlerinnen der Moderne. Munich: Knesebeck, 2019, p. 90.

Regarding a possible idea of a learning program for the Otomís in Mexico, Lena Meyer-Bergner, in a letter addressed to Kay B. Adams on November 25, 1948,[4] expresses her concerns about the Americanization of art in Mexico in order to please the American marked that for the most part was not interested in exploring the cultural richness that a country like Mexico had to offer. In this same letter, Meyer-Bergner asserts that the task of textile art was not to imitate the ornamentation or iconography of foreign cultures but that textile work should focus on generating ideas that exalt its own culture and these notions should be sought in its natural richness, in its tonalities, and its dynamics. This sentence clearly illustrates Meyer-Bergner’s views on what the textile as a medium should offer, and perhaps this could again hint to a possible school for the Otomí weavers. The community should focus on its own visual language. This can be seen in the wallpaper design by Meyer-Bergner with motifs of Mexican flora and also personas that resemble Mexican traditional designs.

[4] Lena Meyer-Bergner to Kay B. Adams on November 25, 1948, Bauhaus Dessau Foundation.

Aware of the richness of this land, Meyer-Bergner focused on the exploration of the landscape and the visual components as we can see in her textile designs. The indigenous epistemologies to be found in this region had a clear influence on the artist’s imaginary, especially in one presence: the maguey plant, one of the sacred plants of Mesoamerica. Mayahuel, the Agave Goddess also known as the Maguey, was, according to the archeologist Nicoletta Maestri, the Aztec goddess of maguey and pulque, an alcoholic drink made from agave juices.

The importance of the maguey plant is also to be found in the material culture of the Otomís; the families are engaged in the cutting, spinning, weaving or twisting of the hard fibers obtained from this plant. This production is considered a normal family affair. From the publication Las Industrias Otomíes del Valle del Mezquital, Meyer-Bergner knew about the relevance and its being sacred. The action of transforming the maguey into fibers is of such a significance, that when the Otomís die, their personal malacate[5] (spindle) is buried with them. This is perhaps one of the reasons why for Meyer-Bergner the visual exploration of this sacred plant was obvious, something that can be seen in her textile designs, possibly making this material the focus of her teaching methods in Mexico.

[5] The word malacate derives from the Nahuatl word malacatl, which means “to turn around” or “to turn on itself.”

This case study was written from the viewpoint of a designer and researcher who attempts to draw attention to the epistemological injustice[6] which the indigenous knowledge, especially that existing in the neotropical realm, has been suffering. The epistemologies of knowledge existing in this area have been marginalized due to external power mandates such as colonization and the perpetuation of western knowledge systems.

[6] Boaventura de Sousa Santos. Epistemologies of the South. London: Routledge, 2014.

Buitrago Garcia is a design researcher, cultural producer and curator based in Berlin. She is interested in design anthropology and in the understanding of non-Western discourses in design and cultural practices. Her engagement with other forms of intercultural dialogue led her to focus on the work of artist and designer Anni Albers and Lena Meyer-Bergner and their understanding of native knowledge(s). Her research focuses on making indigenous knowledge visible in South America and Latin America from a decolonial perspective.