Transcultural intersections and knowledge exchange – Lena Meyer-Bergner and the Mexican culture (1939–1949)

During the first half of the 20th century, Mexico became a significant destination for various figures in art, architecture and design from different parts of the world. With the onset of World War II, the Americas became a refuge for a vast group of European artists, creatives and intellectuals. Among them was Lena Bergner, who, along with Hannes Meyer, arrived at the port of Veracruz on 1 July 1939 with a migration permit designating her as a teacher.[1] Thus, she spent ten years in Mexico where she carried out her creative work always connected to social struggle and her political convictions.

To understand Bergner’s connection with Mexican culture, it is important to consider four specific moments in her professional life in chronological order: the first was her involvement in the Department of Indigenous Affairs’ programme in the Mezquital Valley between 1940 and 1943, the second was her participation in the Society of Friends of the USSR, the third was her collaboration with the Popular Graphics Workshop (Taller de Gráfica Popular) starting in 1942 and finally, her contribution to the 1945 exhibition of the Federal School Construction Programme Administration Committee (CAPFCE).

Each of these professional moments was marked by a sincere commitment to leftist ideology, learned during her time at the Bauhaus and reinforced while she lived in Moscow (1930–1936). It was in Paul Klee’s classes that Bergner understood the importance of studying materials and how knowledge about their use and application was more significant than the design of an object itself. Courses in form theory were fundamental to the development of her career; it was in these classes that she learned about the symbiotic relationship between forms and colours and developed a critical view of textile work which would later resonate throughout her life in Mexico. Additionally, Bergner attributed the connection of various Bauhaus workshops with architectural notions where materials were of utmost importance to Hannes Meyer’s direction.[2]

[1] Migration card, Immigration Department, Archivo General de la Nación.

[2] Klaus Jürgen, ‘Lena Meyer-Bergner’, Form + Zweck. Fachzeitschrift für industrielle Formgestaltung, no. 5, 1981, p. 6.

This was the prelude to her development as a politically active designer that led her to settle in Moscow in 1930, where she soon began to work alongside workers in textile factories during the first Five-Year Plan (1928–1932). She focused on creating propaganda through textile designs[3] related to technological and urban advancements, such as the radio or the construction of the subway in Moscow. Later, in a period of stabilisation, propaganda shifted to the beautification of daily life, and it was at this time that Bergner’s designs became more folkloric.[4] During her time in Moscow, she shared a communal apartment with Hannes Meyer, with whom she began a romantic relationship that would continue until the Swiss architect’s death.

When foreign intellectual, scientific and creative forces were no longer needed in the USSR and political persecution increased, the architect and designer decided to emigrate once more. The first option was Spain; however, the Civil War made this impossible. For this reason, they moved to Switzerland, where Bergner spent some time making hand-knotted tapestries and contemplating nature. Nevertheless, the couple’s political conviction and professional ambitions led them to look towards the American continent. Like other Bauhaus figures such as Ludwig Mies van der Rohe or Josef Albers, they considered the possibility of settling in the United States, but this was not possible due to their political convictions. By 1938, on the recommendation of Alfons Goldschmit, Hannes Meyer visited Mexico for the first time and explored the possibilities of emigrating[5] to a country that had openly proclaimed itself as socialist. From his first visit, he established connections with architects, artists and politicians that paved the way for the Meyer-Bergner family to settle in Mexico in 1939.

As mentioned before, Bergner’s intention was to work as a teacher for the Secretariat of Education, a plan that was thwarted from the beginning. However, after a year, she began working with the Department of Indigenous Affairs on a programme aimed at introducing industrial methods to areas where industries were typically artisanal. As Haydeé López Hernández notes, this institution focused on solving problems affecting the indigenous population, aiming to improve and transform the economic and social conditions of the native peoples.[6]

[3] Sigrid Weltge Wortmann. ‘Bauhaus Fabrics’, Women’s work. Textile art from the Bauhaus, San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1993, p. 109.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Raquel Franklin. ‘Of art and politics. Hannes Meyer and the workshop of popular graphics’, Bauhaus Imaginista Journal, 2018, unpaginated. https://www.bauhaus-imaginista.org/articles/2771/of-art-and-politics

[6] Haydeé López Hernández. ‘Mejorando las artesanías populares. Las políticas del Departamento de Asuntos Indígenas para el Valle del Mezquital’, Saber y tradición. Conocimientos y prácticas en el Valle del Mezquital, Mexico City: Secretaría de Cultura, Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 2022, p. 350.

The department director, Luis Chávez Orozco, after observing Bergner’s skill and talent in knotted weaving, decided to invite her to the programme to have a workshop with this technique in the area of Ixmiquilpan for between 60 and 80 students.[7] There, carpets would be produced for the Inter-American Indigenous Congress of Pátzcuaro, a town in Michoacán.

In this initial approach, we can see a cultural and disciplinary intersection. Starting in February 1940, Bergner developed the academic programme focused on the textile industry of the Mezquital Valley. From an almost anthropological perspective, by daily observation of the activities of weaving families, she studied and analysed the processes involved in working with different fibres and weaving techniques. Based on her observations, both Lena Bergner and Hannes Meyer compiled various images captured by photographer Gabriel Fernández Ledesma,[8] showing Otomi women engaged in activities like the backstrap loom, images which she later translated into other visual works.

After studying the material and economic conditions, as well as the settlement patterns of the population, Bergner determined that ixtle would be the base fibre for production in workshops with various types of looms, a dyeing and a spinning centre where the working method would be cooperative.[9] One of her most significant contributions was thinking of specialised dyeing centres, which would be the factor of change to offer more composition possibilities for a material that had rarely been used for experiments with contrasts.

Bergner’s observations about the feasibility of basing a textile industry on ixtle came to the result that it was viable in terms of extraction and transformation of raw materials. Another designer of the time, Clara Porset, a Cuban-Mexican, also wrote about this material and the Otomi people in 1948. Like Bergner, Porset observed the relationship between the Otomi people and this type of fibre, from the spinning process to the production of fabrics for furniture like chairs.[10] Despite their efforts, in 1943 the project ended without establishing the workshops, due to two factors: first, a cultural issue, as the communication and integration of a foreign woman into indigenous communities and their so-called customs and traditions was an obstacle;[11] second, problems with economic resources that were allocated to different programmes and sectors of the Department of Indigenous Affairs. However, one of the most valuable results of the programme was the manual on textiles she wrote between 1940 and 1943, which allows us to glimpse a theoretical perspective on design and material culture that emerges from textile work, where textiles were seen as objects inherent to human needs with symbolic, ritual and functional significance for societies.

Parallel to her pedagogical and research activities, between 1942 and 1946, Bergner developed eighteen exhibitions about the USSR at various venues.[12] These exhibitions were part of a moment when Mexico carried out extensive antifascist propaganda with national campaigns to generate empathy with the Soviet Union following the country’s fascist invasion of 22 June 1941 by Germany.[13] From that year, Mexico embarked on two major campaigns: the first aimed to highlight a positive image of the United States as part of the Allies, and the second was to work in favour of the USSR and against fascism. In this context, the Society of Friends of the USSR was born. Thus, the government took on the task of ‘shaping public opinion according to the needs imposed by the development of the [war] conflict’.[14]

[7] Letter from Hannes Meyer to Otto Ross, 1 February 1940.

[8] Letter from Hannes Meyer to Eddy Huberman, 20 April 1941.

[9] Letter from Hannes Meyer to Margaret Daambeck, 5 May 1947.

[10] Clara Porset. ‘Muebles populares de México’, Mexican Arts and Crafts, vol. 47, no. 5, January 1948, pp. 161–162.

[11] Letter from Hannes Meyer to Otto Ross, 1 February 1940.

[12] Letter from Hannes Meyer to Margaret Keller Dambeck, 5 May 1947.

[13] Aleksandr Ivanovich Sizonenko. ‘El mundo diplomático de la era de Umansky’, Por caminos intransitados: los principios diplomáticos y científicos soviéticos en América Latina, Mexico: Siglo XXI, 1991, p. 138.

[14] Daniel Luna. ‘Comunistas’, Hampones, pelados y cicatrices. Sujetos peligrosos de la Ciudad de México (1940–1960), coordinated by Susana Sosenski and Gabriela Pulido, Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica, Kindle, 2020), location 5773.

Until then, both Mexico and the USSR had both participated in an antifascist struggle. Yet, at the time they had not had diplomatic relations for over a decade. This situation changed in 1943 with the restoration of the Soviet embassy in the country, the same institution for whose interiors Hannes Meyer and Lena Bergner created a mural and tapestries.

The material for the pro-Soviet exhibitions was gathered by both, but Meyer attributes to the designer the artistic and technical organisation of these.[15] The visual mechanisms used in the exhibitions resulted from her knowledge of Soviet culture and experiences during her time in the USSR. They presented everything from textiles to photos of intellectual and military life. The museographic apparatus consisted of 50 or 70 boards containing between 600 and 700 photographs, drawings, decorative objects, etc.,[16] being a type of setup adaptable to different venues in public spaces for itinerant display. Generally, for these exhibitions, she worked with a photo archive of approximately 5,000 Soviet culture photographs and 2,000 Mexican images.[17] Additionally, through her relationship with the Taller de Gráfica Popular and its members, such as Leopoldo Méndez, Pablo O’Higgins, Raúl Anguiano, etc., she knew well how to reach Mexican masses and what mechanisms to use to convey messages to a population that at that time was experiencing a high level of illiteracy. Lena Bergner remained true to her political conviction, could express it and stand morally tall in the face of the impossibility of returning to Europe.

There has been little discussion about the designer’s work at the Popular Graphics Workshop, but she was an active figure contributing to the artistic and administrative decisions[18] of the publication created by the workshop in 1942: La Estampa Mexicana. She focused on editing, editorial design, graphic production, research and compilation of necessary information for album content. Thanks to her textile experience, she introduced new ways to present the editions with linen-covered folders.[19]

Unlike her textile production, her graphic work in Mexico was constant and linked to her curiosity about rural culture, which led her to explore the rural areas near what is now Mexico City. Together with Hannes Meyer, she undertook various excursions on foot, climbing hills and inactive volcanoes, which sparked her interest in the flora and geological formation of these spaces.[20] The prints El Ajusco visto desde el Valle de Contreras (1947) and Amate (1948) are the designer’s best-known works and products of her long walks to observe Mexican landscapes. In them, we can glimpse her perspective. She narrates the sensations she perceived in nature through images with complex light and shadow games that make the presented forms more realistic. As mentioned before, she never stopped exalting her taste for nature and Mexican customs through flora, botany and rural activities, which she captured in her prints within the Popular Graphics Workshop, demonstrating the importance of landscape in her vision of Mexico.

[15] Letter from Hannes Meyer to Margaret Keller Dambeck, 5 May 1947.

[16] Letter from Hannes Meyer to Margaret Keller Dambeck,5 May 1947.

[17] Letter from Hannes Meyer to Margaret Keller Dambeck, 5 May 1947.

[18] Humberto Musacchio. ‘Historia política de un grupo de artistas’, El Taller de Gráfica Popular, Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2007, p. 47.

[19] Helga Prignitz Poda. ‘La Estampa Mexicana. La importancia de una buena organización’, Estampa y Lucha. El Taller de Gráfica Popular 1937-2017, Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes; Museo Nacional de la Estampa, 2018, unpaginated.

[20] Letter from Hannes Meyer to Arnold Hoechen, 15 September 1940.

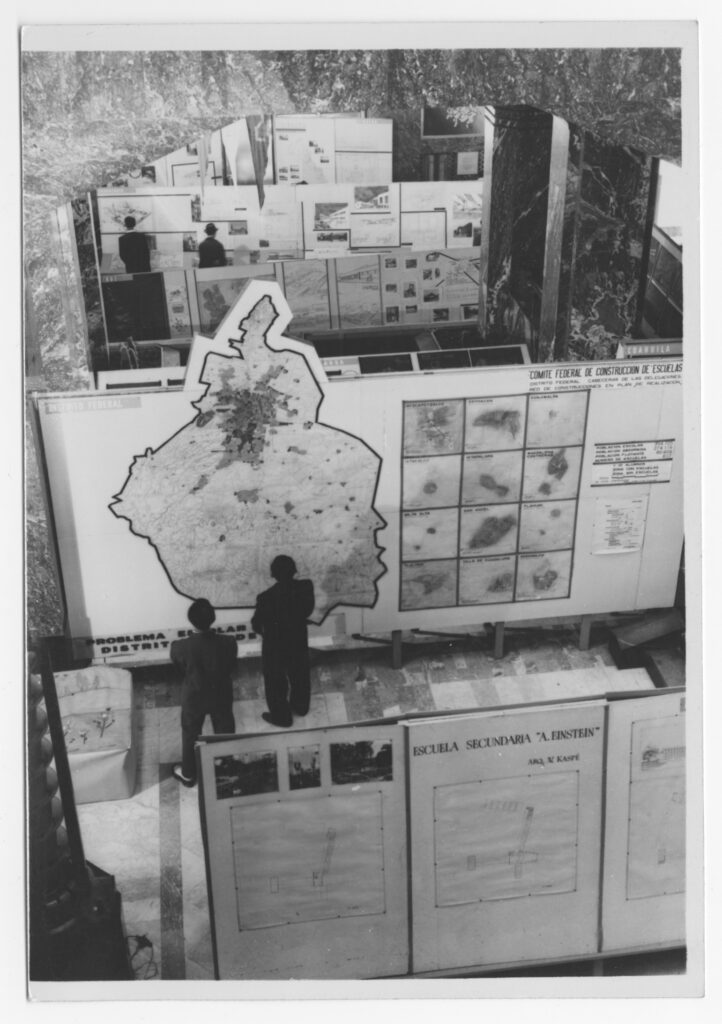

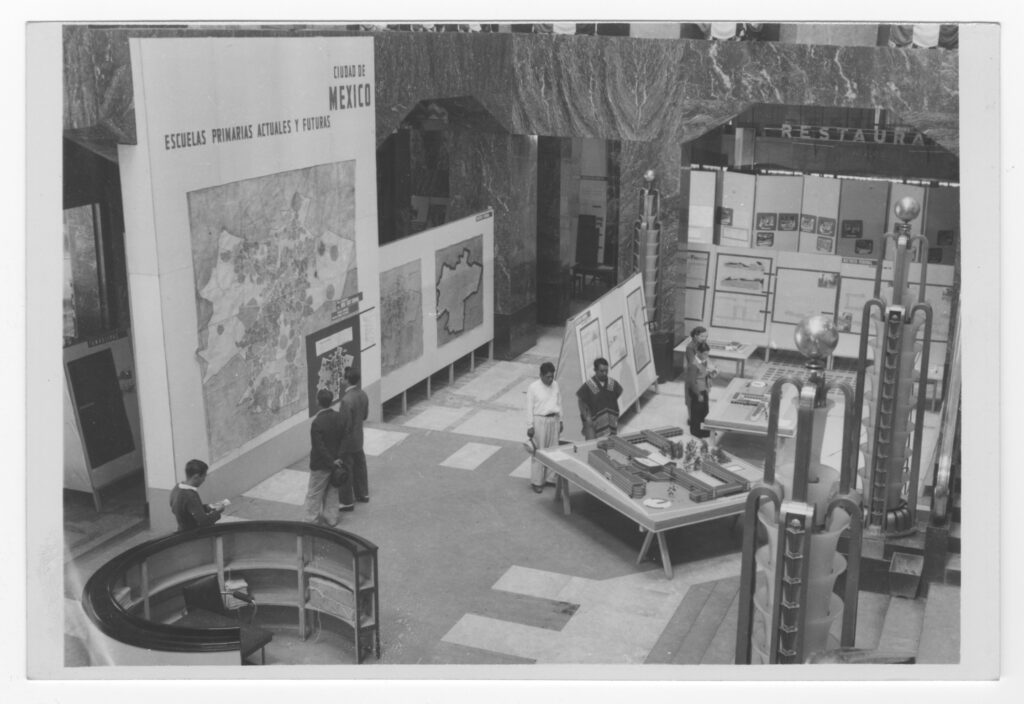

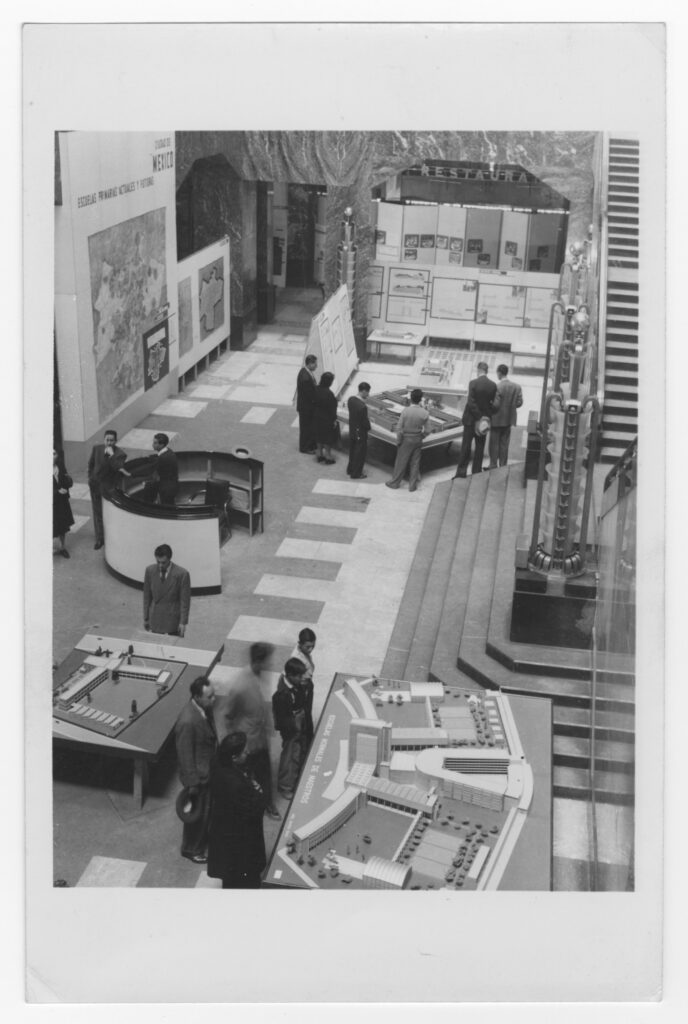

With her experience in itinerant exhibitions and her work in propaganda and research within the Popular Graphics Workshop, it came as no surprise that in 1945, when Hannes Meyer was asked to create an exhibition about the early years of the Federal School Construction Program Administration Committee (CAPFCE), Bergner played an active role. The designer was well-acquainted with the statistical information and the various architectural coordinations at the national level of the program, thanks to Hannes Meyer’s role as coordinator of the photo archive of the governmental organisation during its early years.

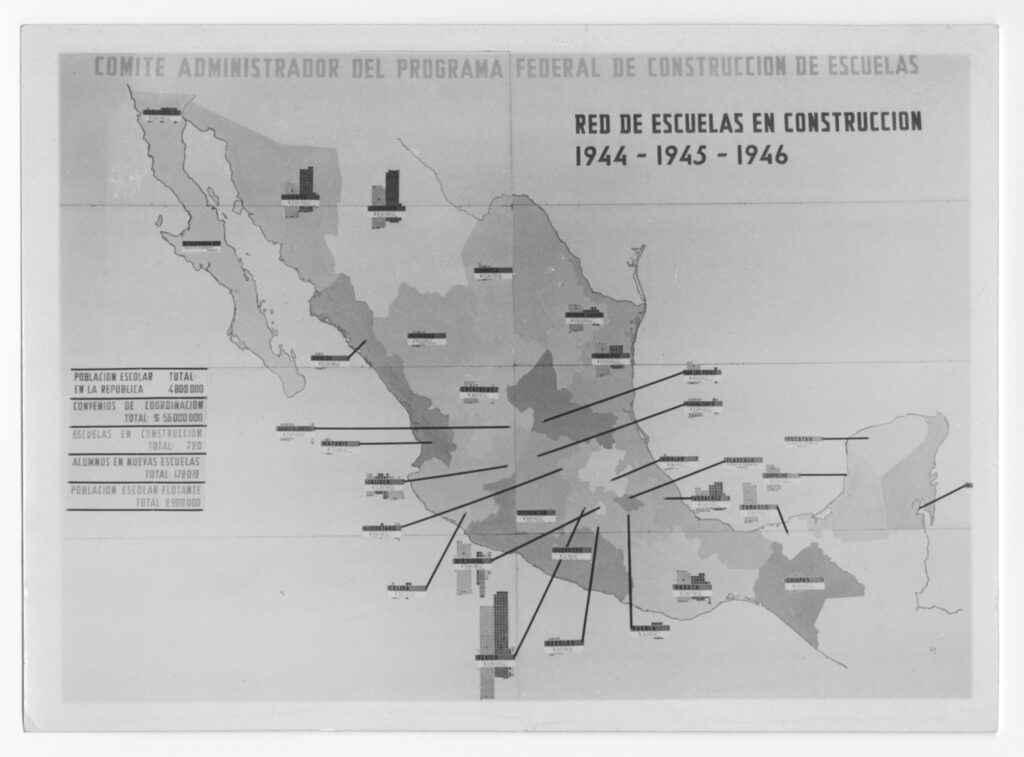

The exhibition, held in August 1945 at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in the capital, played an important role in Mexican politics, serving as part of the government’s propaganda to legitimise constitutional reforms of education and the creation of an institution responsible for configuring an educational project for architecture and furniture design. The exhibition was visited by a large number of people.[21] For this exhibition, Lena Bergner and two assistants created a statistical map of the Mexican Republic[22] that captivated the audience, based on the information worked on by the CAPFCE scientific committees. Once again, the designer approached Mexican geography, but this time through statistical and graphic design activities. As Sandra Neugärtner has mentioned, they used the Viennese method of image statistics or isotype, created by Otto Neurath.[23] It is important to note that a significant contribution to this project was the representation of gender equity in the statistics where Bergner alternated female and male figures to communicate information about schools built and to be built,[24] a revolutionary intervention for the Mexican context.

As this brief overview of Lena Bergner’s professional life in Mexico shows, her path was marked by the exchange of knowledge with other colleagues in the fields of art and architecture. While her work in textiles may not have been the most productive, she was undoubtedly an important figure in the cultural history of 1940s Mexico. Her interactions with indigenous peoples and significant figures in American art history set a precedent for women’s activities in the political and cultural life of a paradigmatic moment for the world. Her exploration of Mexican fibres related to design shows that she was immersed in contemporary discussions, which are perhaps more well-known through figures like Clara Porset. On the other hand, her work in propaganda and activism highlights her knowledge of Mexican politics and her concern for the international situation. Lena Bergner’s profile goes beyond that of a textile designer; she was a woman of many facets and talents, always linked to her political convictions and social struggle, which led her to undertake work in pedagogy and research. Finally, her time in Mexico and interaction with the cultural scene represents a significant act of transculturality essential for understanding how politically engaged artists and architects and indigenous peoples related to different exiles and foreign visitors.

[21] ‘Construcción de Setecientas Treinta y Cinco Escuelas’, Excélsior, 22 August 1945.

[22] Letter from Hannes Meyer to Paul Artaria, 2 October 1945.

[23] Sandra Neugärtner, ‘Die Sozialisierung des Wissens und das Streben nach Deutungsmacht. Lena Bergner: Transfer der Isotype nach Mexiko’, Bauhaus Imaginista: Online Journal, edition 3: Moving away, 2020, unpaginated.

[24] Ibid.

holds a PhD in Art History and is currently an academic at the School of Architecture at UNAM, where she works as a professor at the Center for Industrial Design Research. She is also the general director of the private collection Matter Matters, which contains pieces of design, art, and fashion, and is a member of the board of directors at the Cultural Archive in Nouvel. She completed her Doctorate and Master’s studies in the Graduate Program of Art History at UNAM. Her doctoral research was titled: The Bauhaus at the Taller de Gráfica Popular and the CAPFCE: Works, Exhibitions, and Cultural Management of Hannes Meyer and Léna Bergner. Currently, she is conducting research in the fields of design and architecture focused on the material culture of objects, as well as specific studies on the theoretical ideas of Léna Meyer-Bergner and materials from the Reino Objeto Research Laboratory at the Center for Industrial Design Research.