VKhUTEMAS - Moscow Bauhaus

The creation of the Soviet VKhUTEMAS was preceded by a radical and sweeping reform of art education that occurred as a result of the October Revolution of 1917. Before the revolution, the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts had dominated the vast country for so long and so unchallenged that in creating the new system, they tried to break with the values of the past as much as possible.

The creation of the Soviet VKhUTEMAS was preceded by a radical and sweeping reform of art education that occurred as a result of the October Revolution of 1917. Before the revolution, the St Petersburg Academy of Arts had dominated the vast country for very long and in an unchallenged way. By organising the new system, the founders of VKhUTEMAS tried to break with the values of the past as thoroughly as possible.

Thus, in 1918, in the new capital Moscow, free state art workshops (SGKhM) were created. They resulted from the merger of two schools of art and industry—the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture with the Stroganov Industrial Institute. The curriculum at the SGKhM, called the ‘Renaissance experiment’, claimed to transfer knowledge and experience from the master artist to the student apprentice. The new system was a set of autonomous, individual and specialised workshops under the guidance of master teachers.

Students were admitted to the SGKhM without admission examinations and had the right to choose a workshop, to transfer to another master or to study in a workshop without a leader. There was no general SGKhM programme; each master relied on their skills and principles. Unfortunately, during the two years of its existence, the SGKhM system proved to be inefficient. The number of students was too unevenly distributed between masters, there was no unified programme and not all master-artists knew how to teach. Apprentice students arrived at the school with extremely different levels of training—from those who could not read and write to those who were already skilled in drawing.

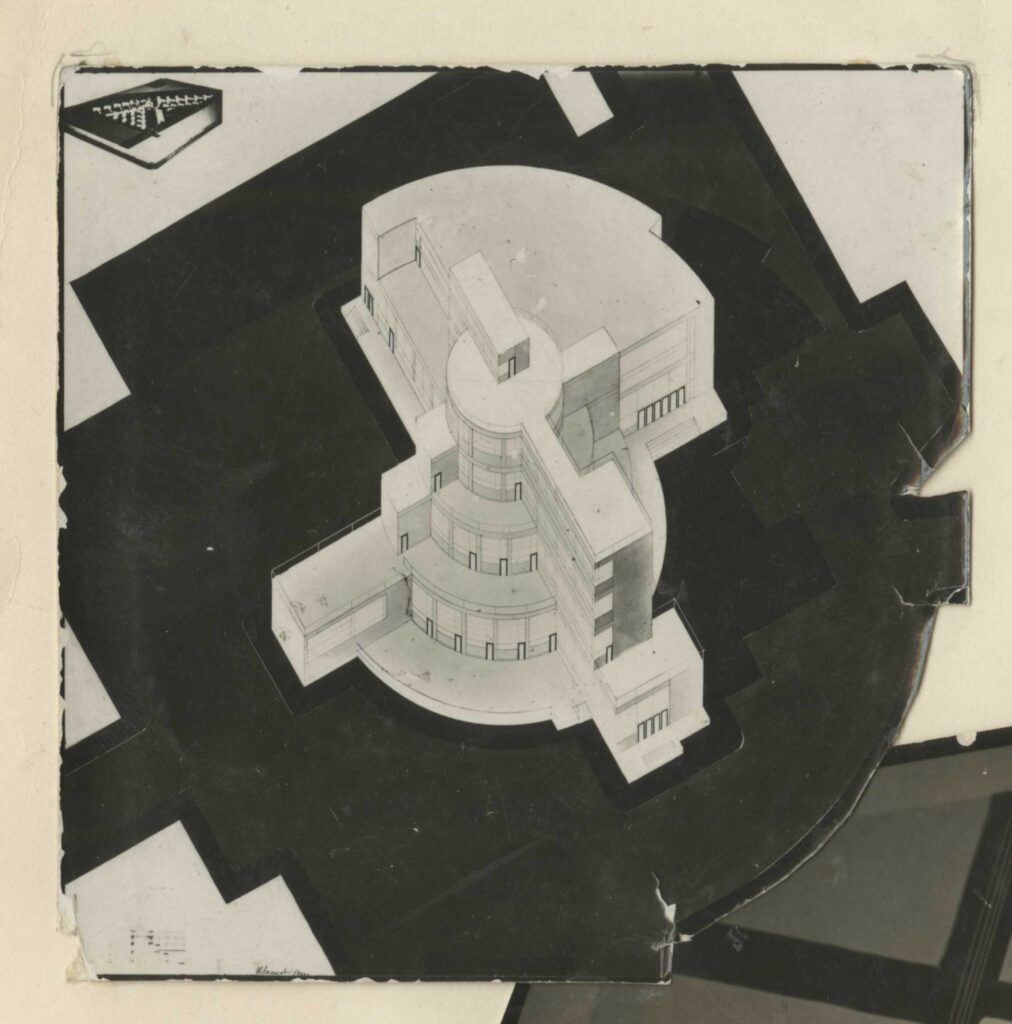

Thus, another reform was needed, which resulted in the emergence of the Higher Art and Technical Workshops or the VKhUTEMAS. The purpose of the reform was to harmonise and consolidate the workshops, to bring the general artistic level of students to the same level and to focus on the training of artists for industry. The VKhUTEMAS consisted of art departments—painting, architecture and sculpture—and industrial departments—ceramics, textile, printing, metal and woodworking. The programme to create a new and improved educational institution was proposed by a young party official, Yefim Ravdel, who eventually became the first rector of the VKhUTEMAS.

It is worth noting that Yefim Ravdel held radically leftist views, so in the early years, the ideas proposed by leftist artists in the VKhUTEMAS prevailed. They were concerned with the issue of training artists for industry and a radical rejection of the art forms of the past, particularly painting. Therefore, the support of the first rector provided a historic chance to representatives of new art trends—mainly constructivists—to finally introduce their ideas into the curriculum.

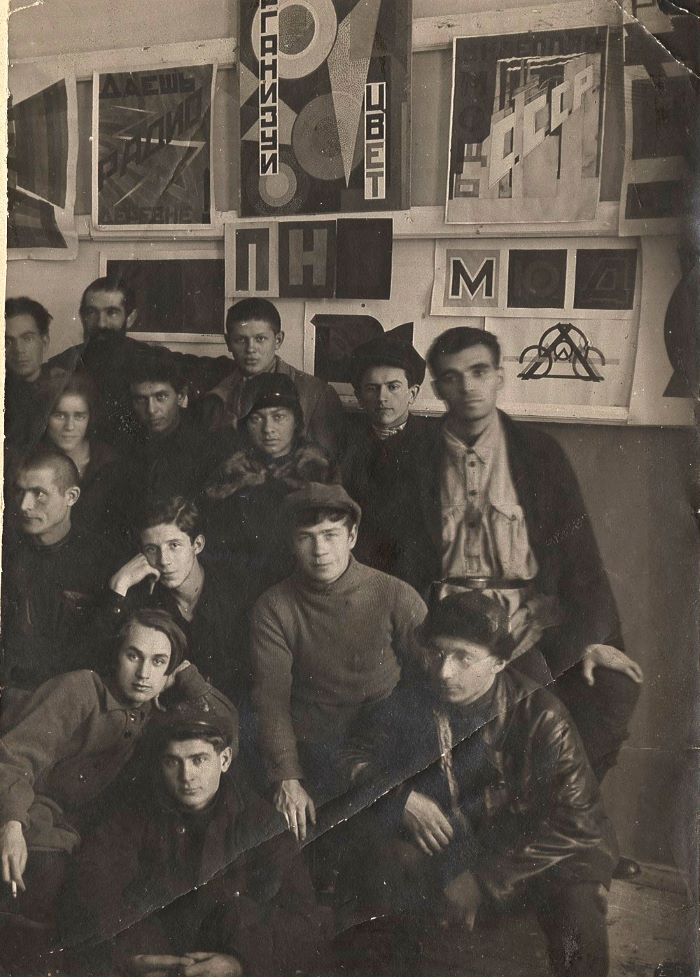

The process of introducing new approaches was met with great resistance from both the faculty and some students. So, throughout the decade of VKhUTEMAS’ existence, the endless internal contradictions kept threatening to tear the school apart. Radicals of various kinds worked side by side with the ‘classics’ who chose not to abandon the traditional academic principles.

One of the biggest challenges within the VKhUTEMAS was the possibility to freely choose a future specialisation. Also, the number of students in the departments was distributed quite unevenly. The majority of new students rushed to the painting and architectural departments. Artists of the left currents agitated students to enter the industrial departments, but the number of already enrolled students as well as the number of those wishing to become industrial artists remained incredibly small, despite all efforts. While the painting and architecture departments had hundreds of students, the ceramic, textile, woodworking and metalworking classes were attended at best by two or three dozens of students.

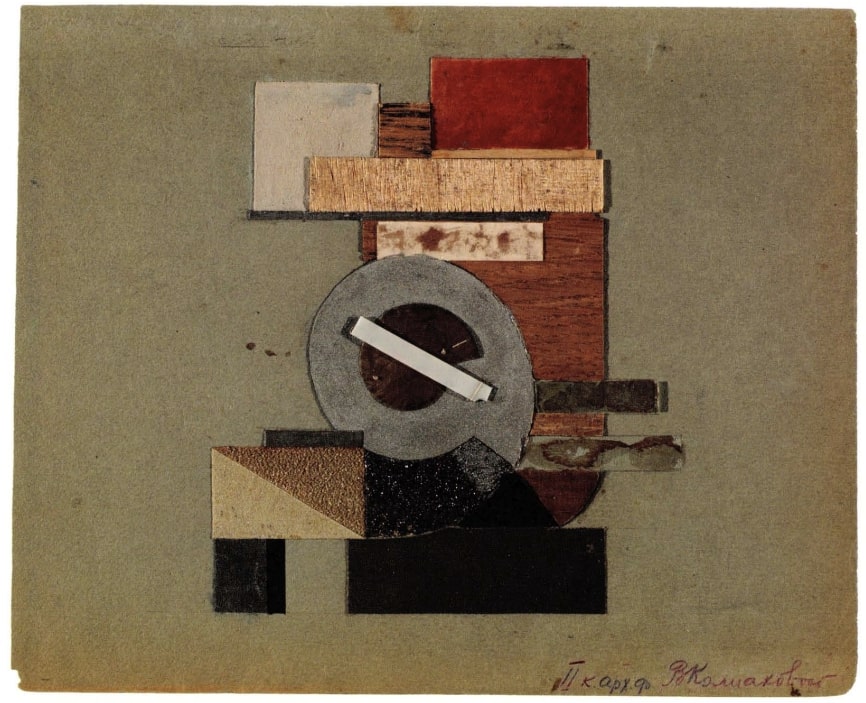

From a historical distance, it is clear that the constructivists were essentially advocating for the creation of design education. However, at the time, only a few people understood what was meant, and the radical demand to abandon painting was very confusing for both faculty and students. In their memories, many students indicated their interest in the proposals of the constructivists but also dreamed of ‘painting with brushes’ more than anything else.

The confrontation between the constructivists and less radical artists ended with Yefim Ravdel being dismissed from his post as the rector and replaced by the much less antagonistic Vladimir Favorsky.

Favorsky, who was a graphic artist, teacher and art theorist, had studied in Moscow and Munich where he had picked up the ideas of formalism directly from the ‘Roman circle’. For the next three years, a completely different tone was set at the VKhUTEMAS. Now, much attention was paid to the general artistic level of the students, which had undoubtedly fallen during the years in which painting had been rejected.

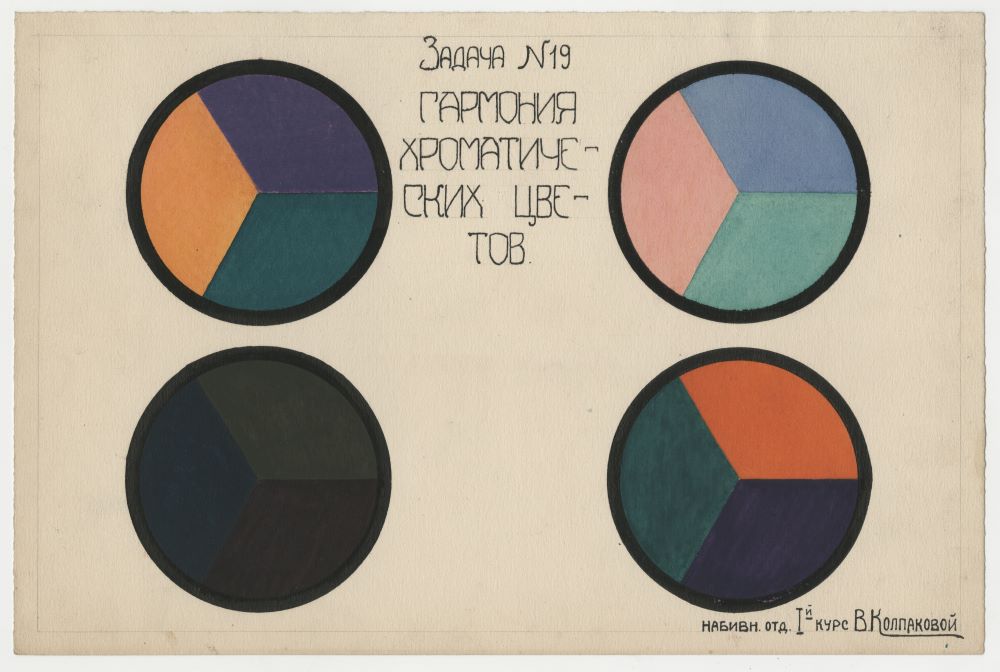

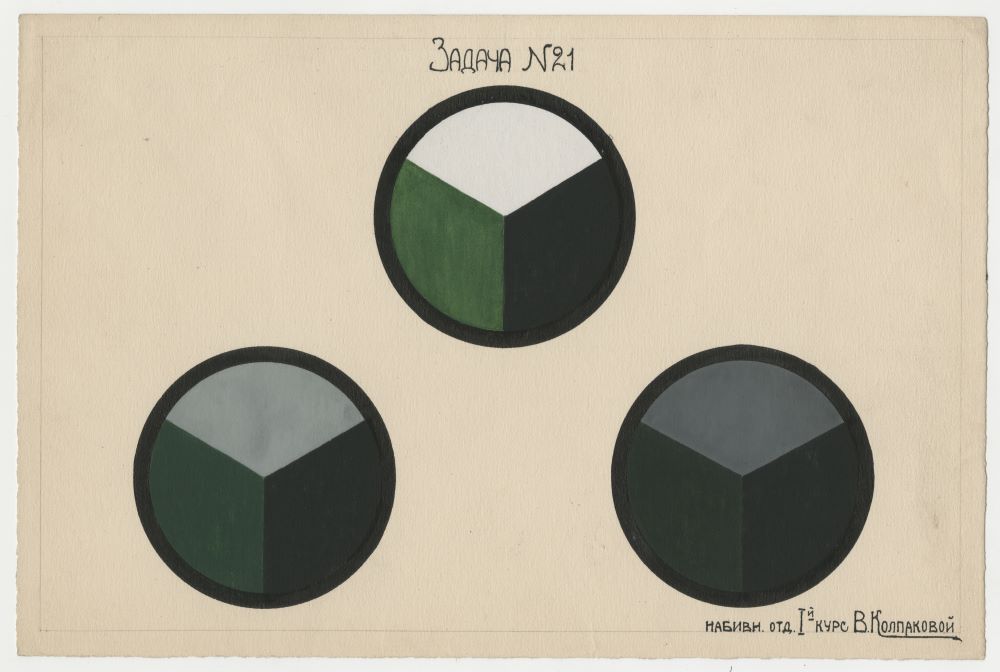

It should be noted that Favorsky did not radically refuse all proposals of the constructivists, despite the existing sentiments to fully return to the pre-revolutionary academic system. For example, he continued the most significant innovation of the VKhUTEMAS—the core division or, as it was also called, the propaedeutic course, which was compulsory for students of all specialisations during the first two years of their education. It consisted of four disciplines: colour, graphics, volume and space. The first year of the core division was the same for all students, and in the second year, students followed disciplines in the context of their majors. This became a solid base for all departments and had a stabilising influence on the entire diverse structure of the VKhUTEMAS.

Favorsky’s attention to the general artistic level was undoubtedly beneficial, but the industrial departments, which were avidly promoted by the constructivists, were at a disadvantage. However, the formation of industrial art had been one of the most important reasons for the creation of the VKhUTEMAS in 1920. Needless to say, this eventually led to the resignation of the second rector, but almost all researchers of the VKhUTEMAS note that the three years of Favorsky’s reign were the school’s heyday.

In 1926, Favorsky was replaced by a new rector—Pavel Novitsky, a sociologist of art who, like his predecessor Yefim Ravdel, largely favoured left-wing artists and constructivists in particular. When the new rector took up his post, the first thing he did was analyse the state of affairs, and he came to the well-known, disappointing conclusion that the main task of producing artists for industry had not been fulfilled in the six years of the school’s existence.

Novitsky concluded that to compensate for this deficiency, the core division should be cut from two years to one year, which shortened the path to professional training. He also emphasised raising the prestige and importance of the industrial departments; under his leadership, for example, El Lissitzky and Vladimir Tatlin came to teach at the newly combined woodworking and metallic department.

Novitsky’s reign also saw major external changes. In particular, the increasingly industrialised economy demanded that specialists be trained in shorter periods of time. So, in 1927, the VKhUTEMAS was renamed Higher Art and Technical Institute (VKhUTEIN), reflecting an internal reform of the whole concept—accelerated training of highly qualified specialists.

All these desperate attempts to train artists for industry faster, even taking into account the complete abandonment of propaedeutic disciplines, which occurred in the last year of the school, in no way helped to instantly solve the very complex problems. The resolution of those would have taken years. Therefore, at the end of the 1920s, the VKhUTEIN failed to satisfy Stalin’s officials, and in 1930, the school was dissolved. Subsequently, some departments were attached to the corresponding specialised institutes of higher education such as architecture, painting, sculpture, printing and textile schools; other departments disappeared altogether, and the incomplete students were sent to other educational institutions.

Despite facing numerous challenges and internal contradictions, VKhUTEMAS emerged as an extraordinary institution during its decade-long existence. It played a pivotal role in shaping the stylistic and formative artistic trends that resonated throughout the entire twentieth century.

Daria Sorokina is an art historian and a doctoral student at École normale supérieure in Paris, holding a Master’s degree in design research from the Bauhaus Dessau. Daria is one of the new generation of VKhUTEMAS legacy researchers, in the school’s centenary year she co-curated the main exhibition on the school and was also the organiser of many events dedicated to the centenary commemoration. Daria is currently writing her doctoral thesis on the deep connections of VKhUTEMAS pedagogy with French painting movements and German science.