Inland – An academy for safeguarding of seeds, animal breeds and knowledge

The virtual space that this issue of the e-journal creates invites readers to think about education as part of a conceptual process and an aesthetic operation in the arts. This is especially important at this moment of uncertainty and growing pressure to transition towards another paradigm of civilisation, involving not only important economic and technical changes, but also a transformation at the very core of the productive model, values and culture.

For three years, I worked with Casco in the Netherlands, a relatively small arts organisation with a very strong propositive and experimental capacity that has long questioned many aspects of the art system and looked at its political economy. From that time, I remember a strong concept central to our joint programme concerning the commons, post-Fordist cultural working conditions or feminist economies in Casco’s research. At the same time, I developed the Inland project. The concept centred on ‘un-learning’. This idea contains many central aspects of the challenges we are facing, among them environmental or social justice struggles.

Un-learning many aspects of the techno-scientific rationality, European anthropocentrism and the faith in economic growth at any cost has become a matter of survival. To un-learn, to recognise – from the Latin re-conoscere, to know again – is to a certain degree a creative exercise and means not only to learn from other subaltern realities such as the peasant and indigenous cosmovisions but also to build upon them, allowing new imaginaries.

Is it maybe in that sense that Friedrich Schiller’s On the Aesthetic Education of Man in a Series of Letters (1795) connected art appreciation and beauty with a set of values. That intention guided different artists to develop projects that went beyond the individual sphere of creation or even beyond what would be considered art in their time. John Ruskin devoted himself to an active critique of the early days of industrial capitalism by defending a form of arts and crafts for the enhancement – also morally – of the everyday. He also promoted different educational initiatives, such a Migratory Dairy School to extend new cheese making techniques amongst farmers as a way to increase their incomes and thus keep the rural areas alive. Another important project he engaged with was the Coniston Mechanics’ Institute, which was established in 1852 to promote lifelong learning and continuing personal development for the workers of Coniston. At that time, the local population was around 1,300, with some 600 employed in copper mines. Without their own building, classes such as woodcarving and lectures on topics like geology, art and local history would take place in the village school located in St Andrew’s Churchyard.

In 19th century Britain, there were well over 700 Mechanics’ Institutes. They were created by industrialists and philanthropists to educate the emerging industrial society in the new technologies of the age. Whilst on the one hand they were clearly instrumental, designed to create a more productive, healthy and enterprising nation of workers, they were also altruistic, offering a broader education in the arts and place for social gatherings – albeit to steer the people away from the public house. Subsequently, such institutes became the seedbed of social reorganisation, democracy, women’s rights, co-operatives, friendly societies and unionisation. With the passing of the Public Libraries Act in 1850, many of these institutes became public libraries or universities (for instance in Manchester, Leeds and London).

During the same period, Russian writer Leo Tolstoy established on his estate the school Yasnaya Polyana for peasant children, in which different innovative pedagogical initiatives were brought to life. In his own words, ‘The school had a free development based on principles established in it by teacher and pupils. Notwithstanding all the weight of the master’s authority, the pupil always had the right not to attend the school and not to obey the teacher.’

In 1921, Indian poet and philosopher Rabindranath Tagore bought a large manor house with surrounding land in West Bengal where he set up the Institute of Rural Reconstruction that came to be known as Sriniketan after its location. The school Silpa Bhavana in close-by Santiniketan had already started providing training in handicrafts. Sriniketan took over the work with the objective of bringing back life in its completeness to the villages and to help people to solve their own problems instead of having solution imposed on them from outside. An emphasis was laid on a scientific study of the village’s problem before a solution was attempted.

In line with such ideas about the reconstruction of village life, a new type of school was also conceived, intended mainly for the children of neighbouring villages, who would eventually offer up their acquired knowledge for the welfare of the village community. This promoted forms of non-formal education amongst those who had no access to the usual educational opportunities. It continued in the 1930s with a training programme for village school teachers. An agricultural college was established in Sriniketan and even a rural research centre was set up in the 1970s.

In Spain in 1911, in the context of the new Republic’s impulse for regeneration – in a divergent thread of history that in some ways now looks like a lost opportunity – many important educational initiatives were launched under the umbrella of the Institute for Free Teaching (Institución Libre de Enseñanza, ILE). The brothers Juan and Venrua Alvarado toured rural areas recording observations about the surrounding villages, the living conditions of the pastoralist communities and the rich and diverse dairy culture in which they saw the main potential for rural empowerment (cheese being the millennia-old form of biotechnological storage for the summer pastures’ protein surplus).

Guided by the idea of the institucionalismo rural as proclaimed by Francisco Sierra-Pambley, the Alvarados prepared a report whose recommendations and proposals remain relevant a century later. Propounding an integrated vision of the landscape in ‘P’ format – pastos, pastores, paisaje y paisanaje (pastures, pastoralists, the peasant landscape and its populace) – they emphasised the strategic importance of native livestock and indigenous breeds while proposing a certain modernisation of traditional cheese-making processes. This has had a significant influence on the Shepherds’ School project I started in 2004.

Another important initiative taken by the ILE included the so-called pedagogical missions, which were founded in 1931 to establish a number of travelling missions to train rural teachers and provide the population with educational and cultural activities such as lectures on the progress of health, hygiene and politics. For example, some cultural activities included theatre and puppet plays, listening to classical music on a gramophone, art exhibitions, and poetry and dancing soirées. As the Civil War and General Francisco Franco’s dictatorship erased these programmes and their memory, at Inland we found it crucial to examine their legacy and reignite their spirit. This inspired the Inland project called Mobile Method, which mobilised crews of artists to (conversely) learn from rural communities, or more precisely, to co-learn by activating a series of artistic tools such as Carthologies, Mobile Kitchen, Radio Trashumante or Microarchitectures of Farming – a sort of collaborative hackathon taking a county as a unit of intervention.

Amongst these experimental educational projects that looked at rural reinvigoration and rural arts and crafts, today we need to re-think, or better said, to un-learn how contemporary art functions, and find out what is to be changed at the core of arts education.

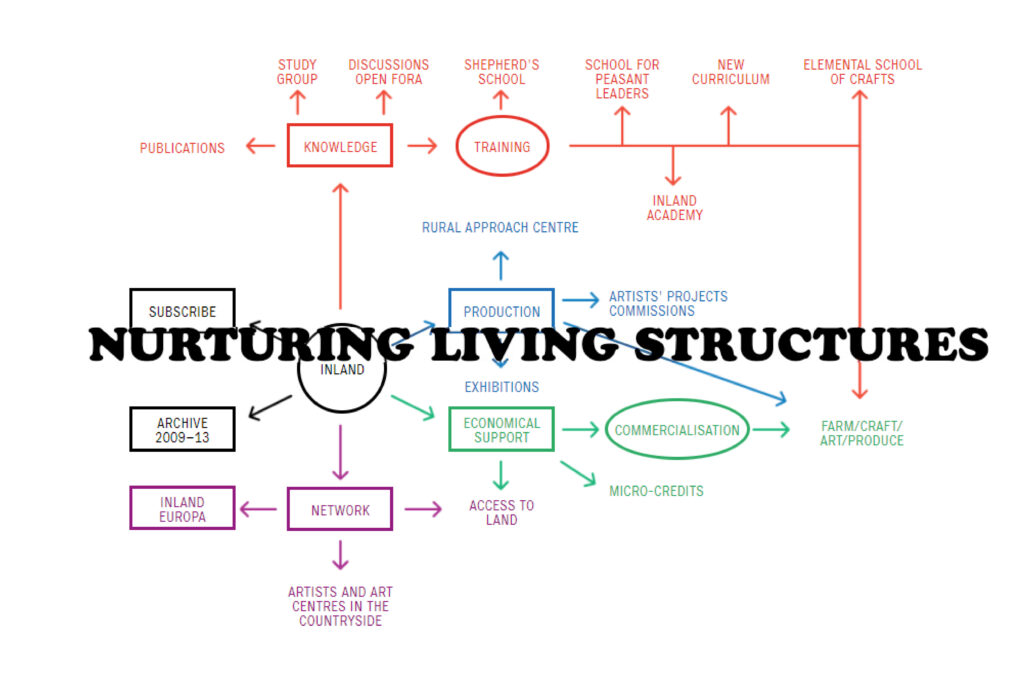

Inland launched in 2009 from a collaborative agency I started in 2009, providing a platform for diverse actors involved in agricultural, social, and cultural production. During its first stage (2010 – 2013) and taking Spain as an initial case study, Inland was engaged with artistic production in 22 villages across the country, including nationwide exhibitions and presentations and an international conference. This was followed by a period of reflection and evaluation, the launch of study groups about art and ecology, and a series of publications. Today, Inland functions as a collective focused on land-based collaborations and economies as well as communities-of-practice as a substrate for post-contemporary art and cultural forms.

Inland has a radio station, an academy, produces shows, and makes cheese. It is also a consultant for the European Union Commission on the use of art in rural development policies, while promoting the European Shepherds Network, a social movement to question those same policies. As of 2020, we are coordinating the Confederacy of Villages, a network of art spaces across rural Europe.

Within this framework, different educational projects have been designed and implemented, targeting different age groups. We work with different schools and with the Museo Reina Sofia’s education department in our Forest-Flock-Classroom, introducing our agroecology awareness programme to around 400 children per year. We also collaborate with the Spanish Commission for Refugees (CEAR) and other official institutions in Spain, offering activities for the children of refugee families. We have worked with rural youth in a project supported by the Ministry of Culture called ‘Loud Voice’, bringing spoken-word artists in to work with teenagers from different villages in order to reaffirm their rural identity. As part of our coordination of the World Alliance of Mobile Indigenous Pastoralists (WAMPI), we facilitate the participation of young nomads in the youth branch of the International Planning Committee for Food Sovereignty (IPC).

We also launched the Inland Academy (inland.org/academy) in 2020 to train young practitioners to develop their projects connecting art, ecology and social change. More than 200 postgraduate students have applied from all parts of the world.

Another important project that we have been supporting is the Shepherds’ School (escueladepastores.es) which has existed since 2004 and aims to transmit knowledge related to mountain pastoralism and land custodianship. Around 100 people apply every year. We support the transition towards living on the land, and we develop cultural strategies to change the perception of what it means to have a form of life connected to the land.

This involves the safeguarding of seeds, animal breeds and knowledge crucial for an agroecological transition and for future generations not yet born. These components of resilient nourishing and biodiverse ecosystems have to be maintained for greater adaptability in times of climate crisis and uncertainty.

In many cases, the work we do is related to a future beyond our lifespan. We are recovering and reforesting an Atlantic Forest which is now a monoculture plantation of eucalyptus, working on improving soil conditions and multiplying bee populations. All these projects combine art, science, vernacular knowledge and social engagement.

A recent development of these ideas came from the documenta 15 in Kassel in 2022 and the concept of the lumbung (a traditional Indonesian communal village barn) to define collective values, ways of governing the collective rice barn and projects that are to build the collective economy. As part of the latter, the lumbung created the Kios (Indonesian for kiosk) and Gallery, sustaining the different local ecosystems by rethinking the sales of merchandise and artwork. Alongside this, we developed both the lumbung land and lumbung currency, which are seen as projects that can build a lumbung value-based economy over the long term.

Since the launch of the working group lumbung land, we have realised the importance of looking at land-based projects and economies as a political commitment to rid art from its dependence on being a service-sector activity funded by public or private investment. The vision involves a form of care for the land as a living support structure with which we co-exist. In this sense, the projects have in mind the agency of the land as a living aspect of the biosphere and thus the need arises to aim our practices at uniting peasant and indigenous communities and becoming custodians of the land to prevent extractivism and speculation. Organisations who have been working in this direction for many years and have started to exchange their practices and knowledge on these approaches include the Jatiwangi Art Factory, Wajukuu, Inland and Mas Arte Mas Accion.

The discussion has been focused on the collective governance of land and development models that start from community as well as on non-human needs, combining agriculture, biodiversity, human culture and the spiritual. Also, we think about how to see the ‘investment’ of the lumbung in specific pieces of the organisations’ land. What would be the return, in financial and symbolic terms? Meanwhile, a land-discursive working group started to come into being. This group focuses on connecting the differing public programmes of lumbung collectives that look at reconnecting to the memory of the land and at how to build an imagery connected to the land which is based on artistic processes and indigenous poetry, songs and images in order to move beyond extractivist modernist uses. It also focuses on land restitution and what that means for ownership, the collective re-creation of narratives, and memories. These two groups became intertwined as learning processes.

Currently, we continue to look at the importance of the transfer and production of knowledge; we are discussing the possible form of a collective Lumbung Land School. The focus we chose for the proposed projects for this lumbung interlokal land project aligns with our vision of agroecology which has a holistic approach and encompasses social, economic, environmental and cultural dimensions. This is not a school in the classic sense; rather, it is a container in which collective learning, harvesting and experimentation happens, the results being brought to the communal village barn, which also symbolises a depository of wisdom.

is an artist, shepherd and agroecologist, living between Madrid, Mallorca and Northern Spanish mountains. Fernando brings together art and agroecology to provide alternative strategies for ecological action and rural revitalization. During its first stage (2010 – 2013) and taking Spain as an initial case study, INLAND was engaged with artistic production in twenty-two villages across the country, nationwide exhibitions and presentations, and an international conference. This was followed by a period of reflection and evaluation, launching study groups on art and ecology, and a series of publications. Today INLAND promotes land-based collaborations and economies, and communities-of-practice as a substrate for post-contemporary art and cultural forms.