Opening the academy: Oskar Hansen’s Pedagogy of Open Form

In 1994, the classical courtyard of the Czapski Palace, the main seat of the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, was filled with fabrics, birdhouses, and sounds. Wide strips of grey canvas, spray-colored and stretched between the buildings, created new spatial relations.

This way, the author of the installation, Oskar Hansen, an architect and professor emeritus of the academy, intended to break the dictate of the closed form – he used this term to describe fully defined, dominant spaces that left no room for individual expression. The installation To Trees and Birds, designed in collaboration with Henryk Górka, introduced shapes that broke the pompous architectural style of the palace complex and the rigorously symmetrical rows of trees to bring out the richness of the existing life in the courtyard.

Stretched above people’s heads, canvas strips emphasized individual trees and highlighted their diverse silhouettes, varied forms and textures of their trunks, and their mutual relations. A low-slung square with a cut-out circle framed the abundance of life on the lawn. The installation transformed the courtyard into a background for events – a non-hierarchical, absorptive space that Hansen called an Open Form.[1]

To Trees and Birds was not his only attempt to transform the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts, both spatially and pedagogically. The architect, author of the Open Form theory and Polish member of the architects group Team 10, had been involved with the school since the 1950s when he returned from a scholarship in Paris. His Western experience – participation in the CIAM Summer School in London and internships in the studios of Pierre Jeanneret and Fernand Léger – was not appreciated during Stalinism. Thanks to Jerzy Sołtan, former collaborator of Le Corbusier and dean of the newly established Faculty of Interior Design, he found refuge at the academy. He continued his teaching activities for 30 years, first as an instructor at the Solids and Planes Composition Studio (1955–1970), then at the Visual Structures Studio (1971–1981) at the Faculty of Sculpture. His classes on the basics of visual composition were a continuation of a prewar course run at the Warsaw academy by Wojciech Jastrzębowski but had an original curriculum based on the Open Form theory.

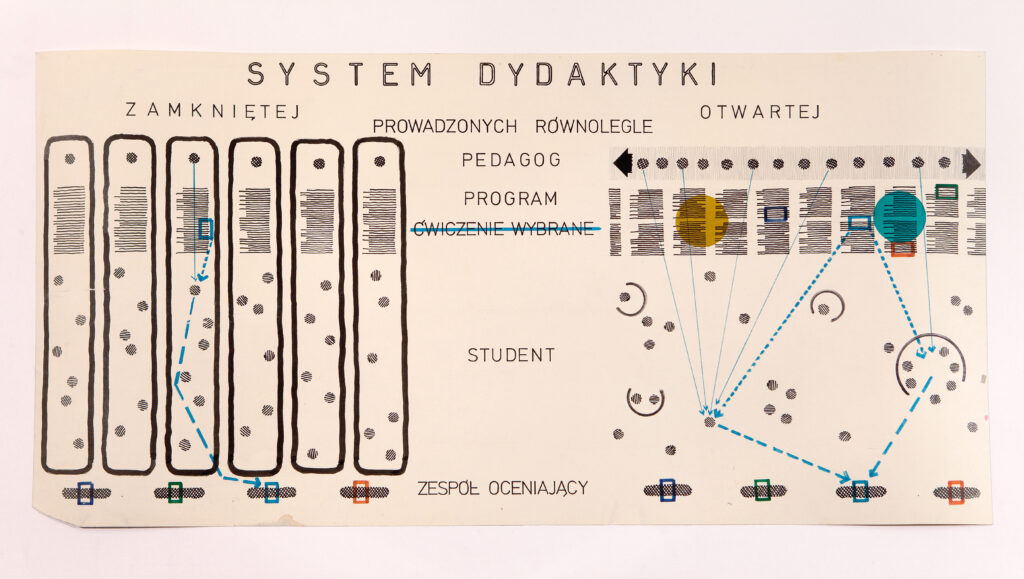

Developed since the 1950s and presented at the 1959 CIAM congress in Otterlo, the Open Form theory defined all areas of Hansen’s activity.[2] In contrast to the closed form which included much of the architectural production to date – dogmatic, hierarchical, fully defined spaces that were mostly a monument to their designers – the Open Form introduced indeterminacy, flexibility, openness to changes, and the users’ co-creation into the field of design (FIGURE 2).

The architecture designed in accordance with its principles was intended to provide a framework for life, act as a passepartout exposing the diversity of everyday events and foster human creativity. It was possible to adapt the theory to different disciplines and scales of design – from exhibitions and pavilions at trade fairs through housing estates designed together with Zofia Hansen, his wife and also an architect, to the Linear Continuous System, the concept of linear cities stretched throughout Poland – and it became Hansen’s life philosophy and his way of describing the world around him.[3]

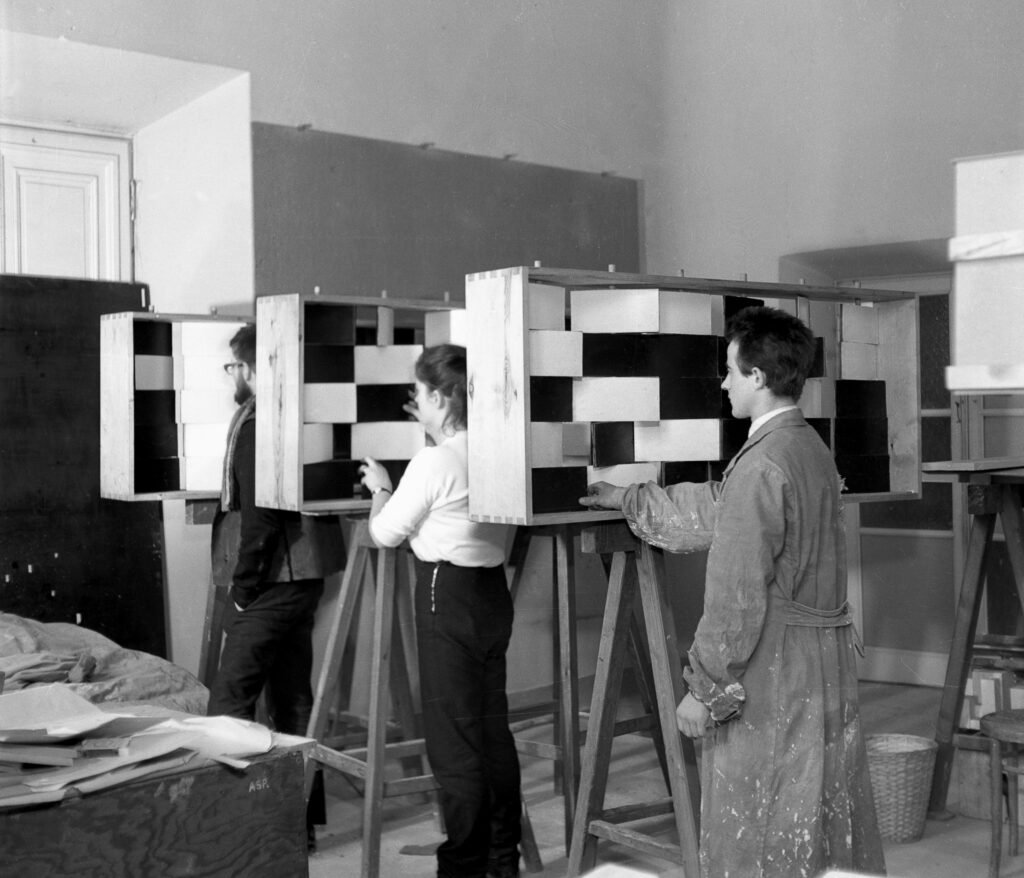

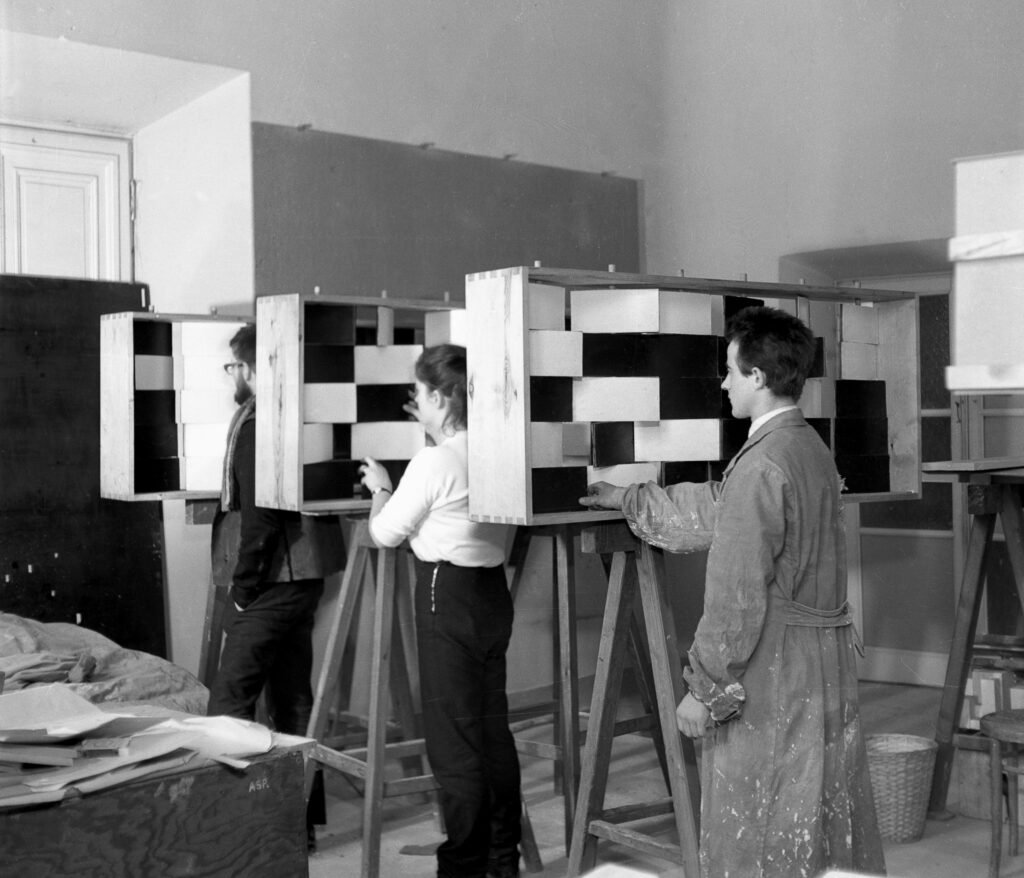

The theory also permeated his teaching practice. The experience of attending the Solids and Planes Composition Studio, compulsory for every student of the Faculty of Sculpture in the first years of their studies, was often recalled by the academy’s graduates as being one of the ideologically strongest in their artistic education, even if they later chose to follow other paths. The curriculum[4] began with a series of compositional exercises based on dichotomies such as heavy and light objects, static and dynamic forms, and contrast of shapes and sizes. These were followed by exercises performed on didactic apparatuses – specially designed devices made from wood and plywood dedicated to studying the problems of “rhythm”, “legibility of complex form,” and “legibility of simultaneous movements.” Some of the exercises, including “Combinatorics – a composition of one’s own dwelling in a multi-story building” or “legibility of large numbers of elements,” directly addressed architectural problems under discussion at the time. For instance, the “Large Number” referred to the concept of the “greater number,” which Hansen and the other members of Team 10 used as a way to address the problem of an ever-growing human population and its impact on the built and natural environment. Another exercise informed by ongoing debates, but unique in its approach, was the “active negative,” a sculptural interpretation of spatial sensations experienced by an individual in an architectural interior. Developed in 1955 as a result of the remodeling of the Hansens’ own apartment, it corresponded to the global interest in gestalt psychology, but unlike the parallel studies of negative space by Bruno Zevi or Luigi Moretti, it was distinguished by the introduction of a subjective, emotional factor.

In the 1970s, the curriculum of Hansen’s studio was enriched by the introduction of open-air group exercises. They had begun outside of the academy as an initiative of young graduates and artists. In December 1971, Hansen participated in a meeting of the Young Creative Workshop in Elbląg where artist Przemysław Kwiek suggested moving the discussion outdoors and replacing words with visual communication – “a performed battle of ‘visual tactics’” that Hansen helped structure.[5] The resulting group action, known as A Game on Morel’s Hill, inspired further exercises performed by Hansen and his students in open-air workshops in Skoki and Dłużew. There, students were encouraged to collectively construct an argument that questioned the hierarchy between author and audience or sender and recipient of a message – each new voice picked up from where the previous one left off, composing a visual, open-ended dialogue.

In 1973, when the academy reclaimed its original premises on Wybrzeże Kościuszkowskie Street, the decision was made to use the building as the new seat of the Faculty of Sculpture. Hansen, the only architect employed at the faculty, was commissioned to design its interiors. He intended to use this opportunity to create a suitable space for the pedagogy of the Open Form. A scheme from 1981 preserved in the collection of the Museum of the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw shows how far-reaching a change he proposed. Instead of the (partly still existing) system of master studios with their unidirectional knowledge transfer, rigid hierarchies, and a finite list of tasks given to students, he advocated for a non-hierarchical, open system in which students could freely shape the program of their own studies, determine their lengths, the way they worked (individually or in freely assembled teams), and the tasks they undertook. They would also summon professors only if they needed their help or advice, which would not only challenge established hierarchies but also clearly demonstrate students’ sympathies and antipathies.[6] When he briefly held the office of dean, Hansen sought to establish the Open Form pedagogy as the official teaching method, but resigned from the position under pressure from other faculty members who did not like his pushing his own teaching ideas on a departmental scale.

The architect’s involvement in teaching visual composition at the Faculty of Sculpture resulted in interesting transitions between disciplines. The Open Form, initially conceived as an architectural theory, became an inspiration for two generations of Polish artists who – also encouraged by Jerzy Jarnuszkiewicz, a professor who ran a parallel studio and introduced photography to the teaching of sculpture – turned to performance and experimental film. Direct references and echoes of the Open Form can be found, for instance, in the oeuvre of Grzegorz Kowalski, Wiktor Gutt and Waldemar Raniszewski, KwieKulik (Zofia Kulik & Przemysław Kwiek), and in the work of Kowalski’s students, including Paweł Althamer, and Artur Żmijewski.[7]

Thanks to Svein Hatløy, a Norwegian architect who came to the Warsaw academy on a scholarship in the 1970s, the Open Form also found its followers in architecture in Norway. The students at the Bergen School of Architecture, established by Hatløy in 1986, visited Hansen in his summer house in Szumin for summer schools in the 1990s.[8] The modest wooden house unintentionally became another teaching device to explain the principles of the Open Form. Filled with didactic apparatus, it explained Hansen’s assumptions through direct experience of them in the space. Now a monument and a branch of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, it helps the next generation to understand Hansen’s architectural thought, in line with his premise that “philosophy is better promoted through space than through a philosophy book.”[9]

is an architecture historian, curator, and editor based in Warsaw. She has curated exhibitions on modern architecture and design including The Clothed Home: Tuning in to the Seasonal Imagination (London Design Biennale, National Museum in Krakow, Lisbon Architecture Triennale, 2021–2022) and Oskar Hansen: Open Form (MACBA in Barcelona, Serralves Museum in Porto, Yale School of Architecture, Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, and National Gallery in Vilnius, 2014–2017). She also served as a curator of the Oskar and Zofia Hansen House in Szumin (2013–2017) and is the co-editor of CIAM Archipelago: The Letters by Helena Syrkus (with Katarzyna Uchowicz and Maja Wirkus, 2019) and Oskar Hansen – Opening Modernism: On Open Form Architecture, Art and Didactics (with Łukasz Ronduda, 2014). She is currently affiliated with the Museum of Warsaw.