Ant Farm – Show/Blow Minds (Learn)

The pop mediasphere (of which they were such insightful savants) best remembers the art group Ant Farm (1968–1978) for the ephemeral delights of their inflatable architecture experiments and for one of America’s most familiar artworks, Cadillac Ranch (1974). Each generation rediscovers the squishy, floating, non-orthogonal fun of a do-it-yourself air-supported enclosure, while the ten Cadillacs, buried nose down in a tail-finned chorus line beside iconic Route 66, continue to offer a loving critique of American car culture’s pleasures and poisons.

“Genius practitioners of the carnivalesque” was Michael Sorkin’s assessment, succinctly capturing Ant Farm’s gonzo architectural reputation.[1] Felicity D. Scott pushes further, though, reading the experimental collective’s work as “a prescient instance of the discipline’s encounter with, attempt to come to terms with, and critical engagement of an environment radically transformed by electronic media.”[2]

Ant Farm looked to do nothing less than reimagine architecture, responding to new electronic technologies, information networks, psychedelic drugs, and a countercultural environmental consciousness being formed through encounters with the lexicon of an emergent planetary culture (from Marshall McLuhan’s global village notion to NASA’s “blue planet” photographs). Their vision of future global media nomads “smok[ing] loco weed around electric campfires” was at once a trippy riff on countercultural, tech-enabled communitarianism and a deadpan projection of architecture understood as interface, not shelter – mobile, multimedia, multichannel, and core to a project of radical life reform.[3]

“EVERYTHING FROM EVERY DAY LIFE MUST BE MADE MAGIC”[4]

Ant Farm joined a number of young North American design communes emerging from the socio-cultural effervescence of the 1960s to challenge and remake what they decried as architectural pedagogy’s stultifying, technocratic framework. The context for their experiments was intense campus ferment and the influence of a global “anti-school,” as Beatriz Colomina has put it, clustered around the thinking of figures such as Buckminster Fuller, Stewart Brand, Victor Papanek and Ivan Illich.[5]

Following Archigram’s earlier lead, they styled themselves as countercultural rock groups with the mirrored sunglasses and names to match—Southcoast, Onyx, Pulsa, Zomeworks, Kamakazi Design Group, Space Cowboys, All Electric Medicine Show, etc. Largely through ephemeral, interactive, building-focused events (“build-in” workshops, “moment villages,” “response environments”) they looked to dissolve boundaries between students and teachers, and between work in the university and outside of it.[6] Architectural education was radically recast as an expanded site for situated learning, directly engaging with pressing environmental and socio-political challenges.

Ant Farm was launched by Chip Lord, Doug Michels, and Curtis Schreier in the psychedelically auspicious year of 1968 and explicitly defined as a “platform for educational reform.” One of their first actions was to disrupt the California Council of the A.I.A.’s annual convention with flyers questioning the profession’s capacity to address the problems of “the black ghetto, of the urban poor, of disoriented youth,” and arguing the event’s speakers be replaced with “real trips, not instructive ones.”[7] Elsewhere, they directly infiltrated sites of architectural education. Projects such as Astrodaze and Time Slice (1969) at the University of Houston were experiments in “life art” that discarded conventional lectures for overnight beach happenings where “everything from everyday life must be made magic,” and camping in the city’s Astrodome stadium, where students spent the night “on and in a 60-foot parachute held aloft by helium balloons.”[8]

Non-hierarchical, freeform educational modes –echoing the radical prototypes of the recent free/anti-university movements – were key to Ant Farm’s ambitions to dismantle the hierarchies and unidirectional information flow of architectural pedagogy. They also keyed into the countercultural refusal of the role played by the university in training compliant subjects for the military industrial complex.

Beyond infiltrating and remaking professional education, Ant Farm’s pedagogical experiments were eventually marshalled towards establishing radically alternative modes of life. Resonating with the period’s liberatory ideals, they pushed ideas of learning as a “continuous life process” and the need to break from traditional pedagogical and professional institutions, spaces, and modalities.[9] An early example of the group’s acid-fuelled agitprop declared their purpose as:

Show/blow minds (learn) environmental alternatives (urban-eco commune/high tech pneumads/pneufamily) […] furthering super consciousness of clean ecological living + openning [sic] man/machine patterns to eco-consciousness: with open ended media systems and closed life support systems: how to live an eco-reality will [read: while] “truckin down the line”[10]

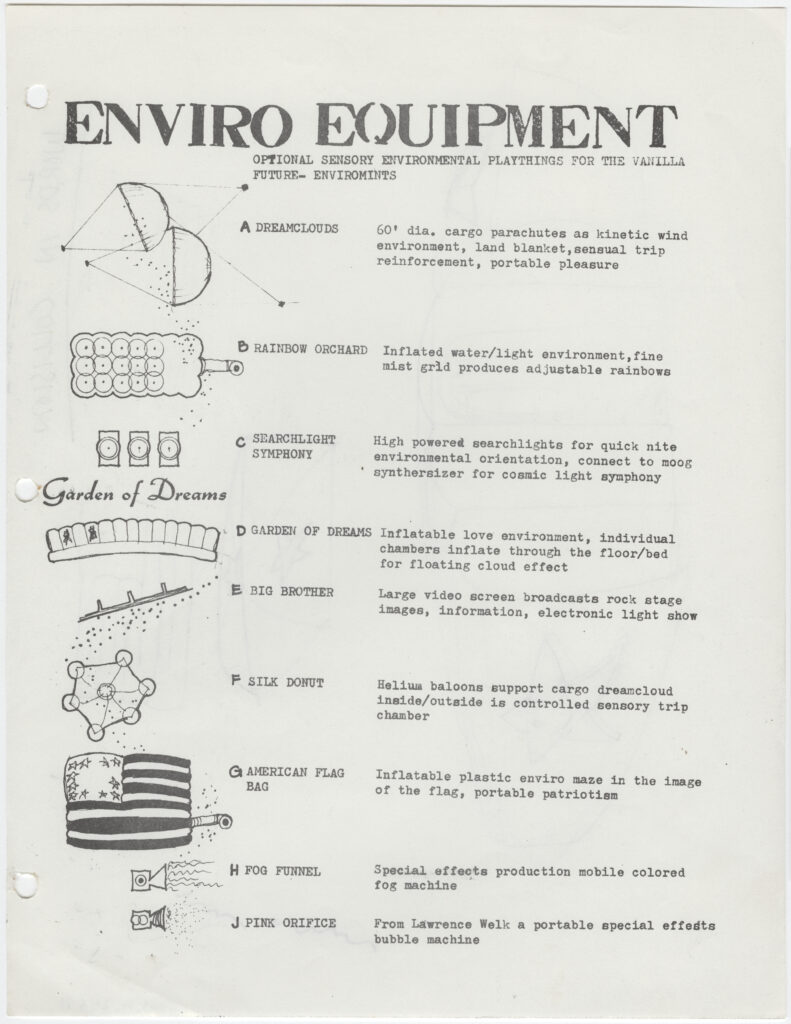

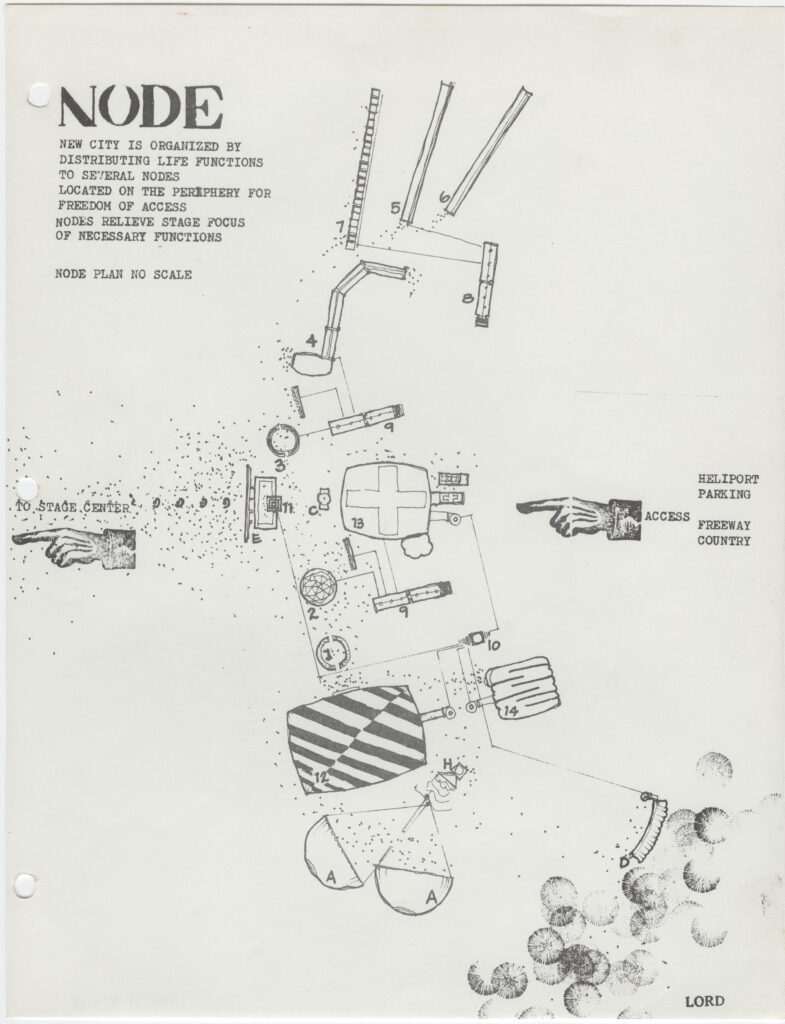

Through their early educational experiments Ant Farm began establishing a toolkit for this broader social and political agenda. Their “enviro-equipment” embraced the conjugative possibilities of camper vans, video portapaks, poly film, industrial fans, LSD, the rock festival format, and endless road tripping. Temporary events, creating counter-architectures in the gaps of America’s infrastructural networks, offered intense sensory experiences through “Dreamclouds,” “Rainbow Orchards” and “Pink orifices.”

The more seriously utopian side to the spacy happenings of this hippie nomadology was a desire to deploy advanced technologies in everyday life, away from their dominant milieu and toward other ends. Ant Farm’s establishment of their “urban eco-commune” headquarters in Sausalito in late 1969 signaled an intensification of this agenda – the group gained more members, becoming “like a large commune” and engaging with Northern California’s ecologically conscious, communitarian design counterculture.

Ant Farm’s visions of pedagogical transformation resonated with the prevailing countercultural orientation toward horizontal information networks and do-it-yourself education (promulgated most famously in the Whole Earth Catalog). Inflatables – the pneumatic structures Ant Farm referred to as “pillows” – exemplified the group’s architectural means for constructing the desired transformative mobility and interactivity.

For the counterculture, inflatables materialized qualities of ephemerality, flexibility and freedom, allowed users to quickly shape their own environments, and offered an appropriate counter-form to conventional, “square” architecture. As Caroline Maniaque notes, “instead of the rigid walls associated with fixed behavior patterns, the supple surfaces promoted radically different behaviors – fluid, free, unexpected.”[11]

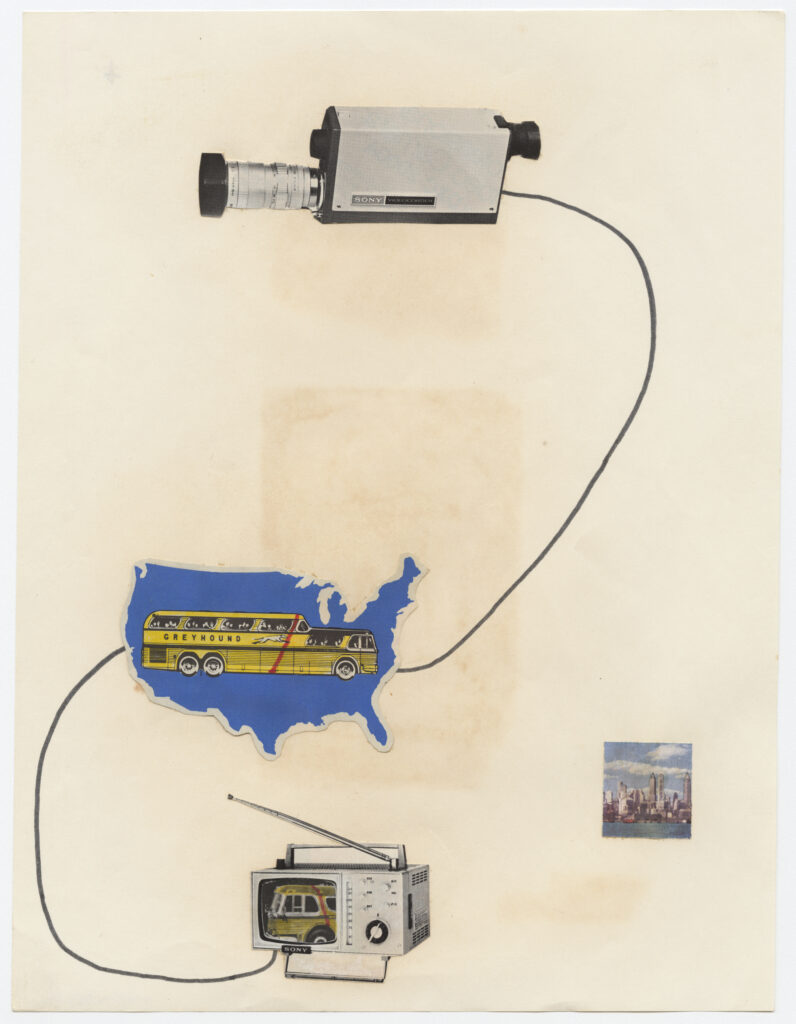

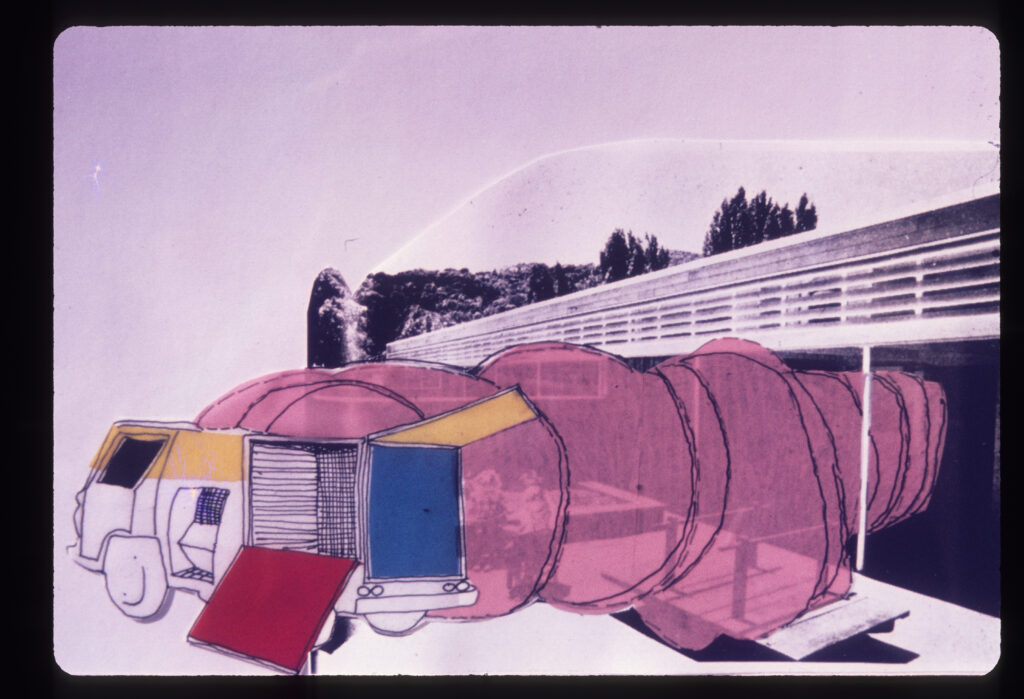

In support, Ant Farm’s customized Chevrolet Media Van carried the required polyethylene films, adhesive tapes and tools to assemble the pillows and provided power to air pumps that inflated them. However, the Media Van was much more than just transportation. Blending influences from NASA’s closed-system life support modules, American hot-rodding culture, and military hardware, it was kitted out with extensive electronic equipment for audio, film and video recording and playback. It also towed the off-grid living unit “Le Roy”—a trailer containing a kitchen, inflatable shower, solar collector, and ICE 9 (a five-person inflatable Ant Farm lived in while on the road).

The Media Van, and the inflatables it could deploy, enabled Ant Farm to rapidly assemble its responsive educational environments for a new community of environmentally-conscious, cybernetically enhanced nomads.

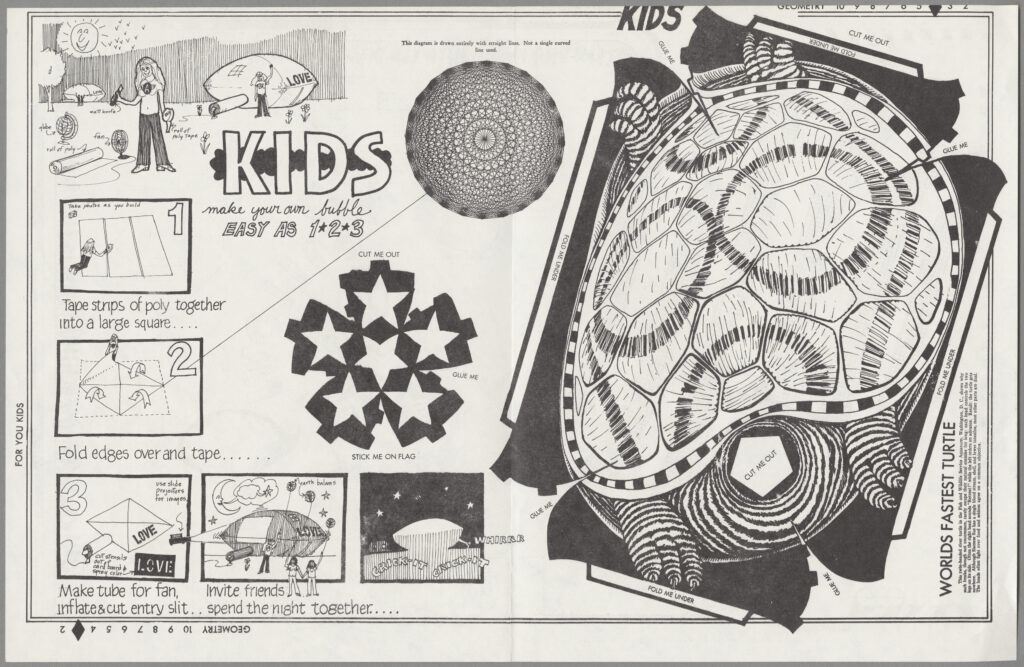

The inflatables and the Media Van were documented in the Inflatocookbook, a do-it-yourself manual first published by the group in 1970.[12] The Inflatocookbook gathered evidence of Ant Farm’s experiments to date as well as assembling and making the information and skills they’d learned accessible to an audience well beyond the architectural scene they emerged from.

The book connected to pioneering alternative architecture manuals such as Steve Baer’s Dome Cookbook (1968), Sim Van der Ryn’s Farallones Scrapbook (1969), Lloyd Kahn’s Domebook (1970), and even Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog (1968–1972). Inflatocookbook’s design and production also owed much to the methods of the countercultural media flourishing in North America. A bricolage of varied paper stock, stencils, typefaces, silkscreens, photo collages, and cartoon illustrations, it offered step-by-step instructions in a humorous tone and invited readers’ contributions to form a feedback loop.

The Inflatocookbook plugged Ant Farm’s ideas of pedagogical reform directly into a countercultural educational ethos of direct, playful access to tools and information.

The Inflatocookbook also outlined Truckstop Network, which offered the even more ambitious vision of a wholly dispersed alternative learning community:

[W]hat we are talking about is an institution, a communication network of places like ours, where media nomads can pull in off the road (earn College Credit!), repair a truck, video linkup throughout, tools of your trade, nutrients for every need.[13]

Ant Farm’s spring 1970 “Demonstration Tour” of schools, colleges, countercultural conferences, and eco-activist interventions put the Truckstop Network idea into motion. It came at the high point of their inflatable period and centered on the 50 x 50’ Pillow – an inflatable commissioned for a failed rock concert in Japan.[14] Tour stops included the Earth People’s park and the University of California’s Sproul Plaza in Berkeley to stage their famous Air Emergency performance for Earth Day (a pranksterish “survival event” in which people were told that Ant Farm’s pillow was the only safe space to escape deadly air failure). However, two other events in which they participated during the tour period clearly laid out the wider stakes for the group’s educational experimentation.

First, in March 1970, Ant Farm participated in the Freestone Conference, at the invitation of its organizer, Berkeley architecture professor Sim Van der Ryn. Van der Ryn and his collaborators at the Farallones Institute had undertaken a series of architectural experiments in California public schools with progressive educators influenced by the free school movement. “We are dominated by furniture,” contended Van der Ryn and involved students in constructing inflatables and zonohedral structures that were simultaneously exercises in learning by doing and experiments in radically reconfiguring classroom space.

The Freestone gathering extrapolated in part from these efforts to break down rigid institutional spatial orders, emphasize non-hierarchical, collaborative design and an open-ended learning process. The goal, as Van der Ryn put it, was “to learn to design new social forms, new building forms that are in harmony with life […] to build a floating university around the design of our lives.”[15] Ant Farm’s 50 x 50’ Pillow was an important contribution – a focal space for much of the event’s activities.[16] Its significance for the Freestone community demonstrated that the inflatable (accompanied by the child-friendly Inflatocookbook) had traveled well beyond the realm of rock concerts and avant garde art interventions – it was comprehended as a more universal tool for establishing an alternative society.

In June 1970, again at the invitation of Van der Ryn, Ant Farm attended the International Design Conference in Aspen (IDCA), themed “Environment by Design.” Here, they were part of a contingent of “Environmental Action Groups” including Ecology Action, People’s Architecture Group, Environment Workshop, and Farallones Institute. Ant Farm arrived in their Media Van and, contrary to the organizers’ proscriptions, set about assembling their Spare Tire Inflatable. The disruption did not end there.

The “Berkeley/Ant Farm/Mad Environmentalist Coalition,” as Reyner Banham disparagingly referred to them, were involved in a series of events that derailed conference proceedings. Non-programmed interventions (such as a chaotic name-badge swap session) and a series of provocative proposed resolutions (criticizing the IDCA’s lack of real commitment to the environmental theme) highlighted ideological differences between the young counterculture radicals and venerable IDCA regulars. The environmental collectives and activist architects, with Ant Farm prominent among the voices, vigorously challenged any acceptance of designers as uncritical operatives within a capitalist, profit-driven system. They also demanded a more interactive, responsive conference format and a commitment to more authentic engagement with social and environmental concerns. It was an ambitious attempt to re-educate the IDCA establishment.

Alice Twemlow has described the tumultuous conference and its aftermath in detail, showing that the IDCA board was, indeed, shaken by the events, and experimented in subsequent conferences with more participatory formats.[17] The “Berkeley/Ant Farm/Mad Environmentalist Coalition” contributed to reshaping the institution along countercultural lines. However, as Twemlow notes, the IDCA’s embrace of these changes might be regarded “as a textbook example of the capitalist system’s ability to assimilate its own inherent contradictions, rather than resolving the real issues through definitive action.”[18]

Around 1971, Ant Farm’s “Truck stop fantasy one” bulletin would emphasize the group’s conception of an open-ended pedagogy for an emerging post-institutional world – an education system as “a continuous process with no finish with a degree and no start in ‘school.’”[19]

It went on to ponder, “what happens when distinctions between gradeschool highschool college [sic] are removed? Incidental [sic] education for wandering learners little kids and old guys growing with mutual feedback.” Ant Farm’s signaling here again of education as a continuous, cybernetic process, outside the strictures and structures of traditional pedagogical institutions resonates with the counterculture’s liberatory ideals and rhetoric. However, as Felicity Scott has soberly noted, the imagined freedom was in no way guaranteed.[20]

Open-ended, interactive forms of education and socialization are all too smoothly deployed in what Gilles Deleuze termed a control society – training the nomadic subject of post-industrial culture in a requisite, continuous flexibility. To what extent Ant Farm recognized these ambiguities is open to question, making the revisiting of their propositions to reckon with the implications an endlessly valuable exercise.

is Head of Architecture at the University of Sydney. His historical research on international countercultural and ecological design experimentation has been published widely across scholarly, professional, and popular media. He is actively engaged in creative and curatorial practice – collaborating with organizations such as the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, the Christchurch Art Gallery and the Lismore Regional Gallery. He serves on the editorial committee of the Architectural Theory Review, the International Advisory Board for Counterculture Studies, and the steering group of the Counterculture History Coalition. Whenever he gets the chance, he can be found riding a bike.