Sim Van der Ryn and the “Outlaw Builders”

Sim Van der Ryn’s exploration of counterculture DIY building was personal and implicitly political. When shared through architecture school studio culture, it became pedagogical and professionally subversive as well.

In his foreword to the 1973 self-builder’s publication Handmade Houses: A Guide to the Woodbutcher’s Art, Sim Van der Ryn, a Berkeley professor of architecture, confessed the difficulty of mastering do-it-yourself (DIY) craftsmanship and asserted its importance as a means of mending divisions “nurtured by the machine metaphor, by the separation of one’s work from one’s identity.”

”In 14 years of architectural practice I never designed a mortise and tenon joint because it was too much handwork and at carpenter’s wages, far too expensive. Now I am learning to make them myself. It is taking me a long time to get over the guilt of spending days hard at work learning to do the things I wasn’t trained to do. It is taking a long time to accept the simple satisfaction of doing what I am doing, living in the present.”[1]

In identifying itself as a licensed vocation, the architecture profession relies on the distance between its design practices and those of amateurs to maintain its occupational identity and social status. Professionalization, as Gerry Beegan and Paul Atkinson point out, “acts as a system of exclusion by setting up criteria that, intentionally or unintentionally, bar individuals and groups on the basis of money, class, ethnicity and gender.”[2]

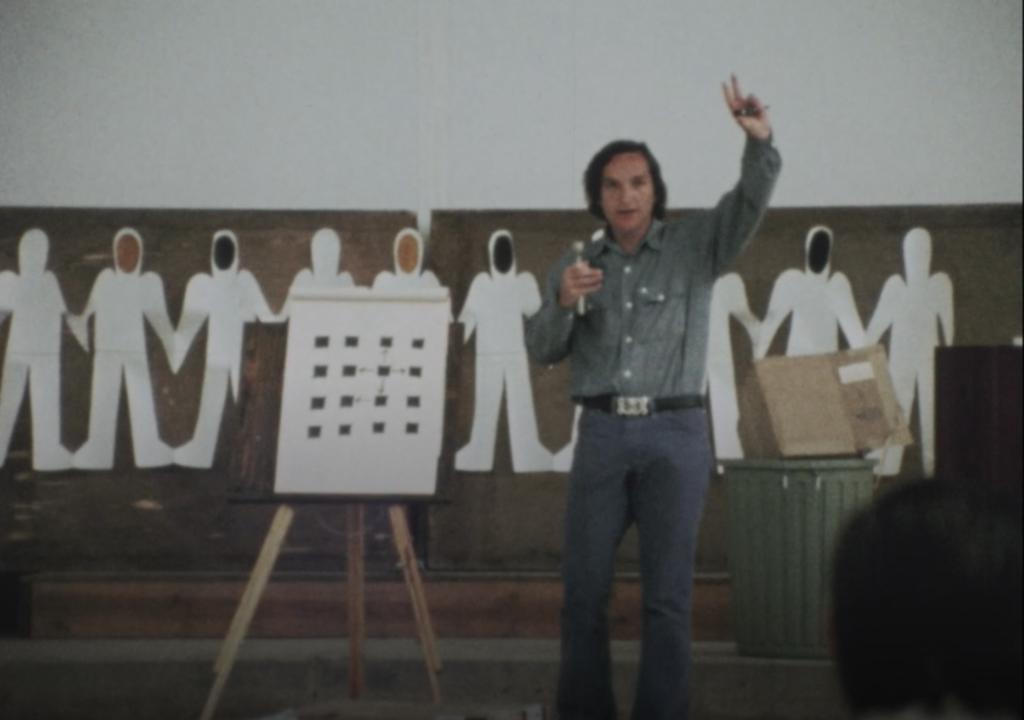

Architecture training programs and their licensing examinations limit entry to the design profession and reinforce professional norms and values. The system’s inertia keeps change slow and manageable. During the 1971–72 academic year at Berkeley’s College of Environmental Design, an elective studio succeeded in circumventing those regulatory mechanisms. Listed in the course catalog as “Arch 102ABC: Integrated Synthesis of the Design Determinants of Architecture,” its counterculture agenda was revealed in the two names by which the course was more commonly known – “Making a Place in the Country” and the “Outlaw Builder Studio.”

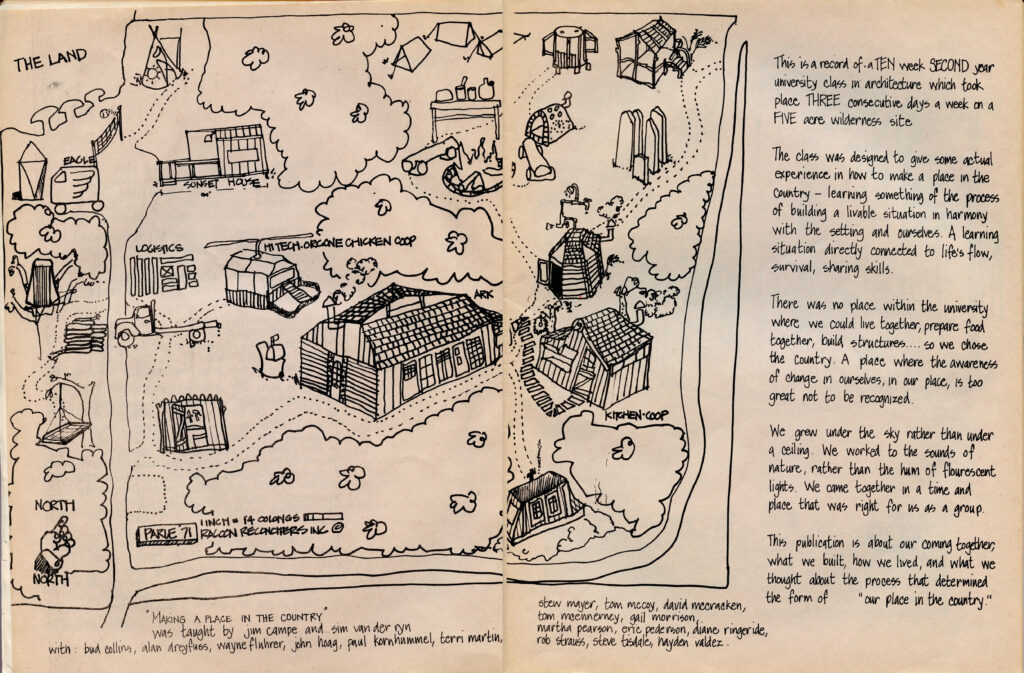

Instructors Sim Van der Ryn and Jim Campe recruited students for a full academic year of research and construction on a forested hillside adjacent to the Point Reyes National Seashore in Marin County. Metaphorically, Arch 102ABC was a Trojan horse. Its “on-site experience in the theory and practice of basic building design, land use, and village technology” injected the methods, ideals, and building tasks of the hippie back-to-the-land movement into a professional design degree program.[3]

Van der Ryn and Campe possessed ideal credentials to stage a fifth-column subversion of professional design pedagogy. Despite his “disgruntlement with architecture school” as a student at the University of Michigan, hearing Buckminster Fuller lecture there sparked an “epiphany.”[4] A second one came in the mid-1960s, around the time he accepted a teaching position at Berkeley. His participation in a clinical study gauging the impact of LSD upon “creatives” – a category that included scientists, engineers, and designers – unlocked the doors of perception.[5]

When Berkeley students and hippies appropriated a block of vacant University-owned land in 1969 for the DIY commons called People’s Park, Van der Ryn became fascinated with its “spontaneous participatory design process” and then horrified by Governor Ronald Reagan’s militarized response. Civilian gunshot injuries, the death of a bystander, and the spectacle of a military helicopter spraying the campus with a virulent form of tear gas devised for use in Vietnam “shook me awake,” as Van der Ryn later recalled.[6]

Counterculture values suddenly permeated his teaching and design efforts. In 1970, Van der Ryn participated in two epochal design conclaves. He convened “Freestone,” an outdoor festival of hippie makers, “to learn to design new social forms, new building forms that are in harmony with life.” Accompanied by a band of eco-freaks bused to the Colorado using redirected university research funds, Van der Ryn disrupted the International Design Conference at Aspen.[7]

Joining forces with Jim Campe, an environmentalist and “free school” reformer, Van der Ryn co-authored a DIY publication, the 1971 Farallones Scrapbook, dedicated to applying the lessons of hippie self-build methods to both schoolroom environments and childhood pedagogy.[8] Collaborating again to offer a Berkeley design studio, Van der Ryn and Campe mounted a counterculture assault on establishment design training – conducted, remarkably enough, from within an academic program certified by the National Architectural Accrediting Board, an organization created to regulate and reproduce the profession’s standardized competencies.

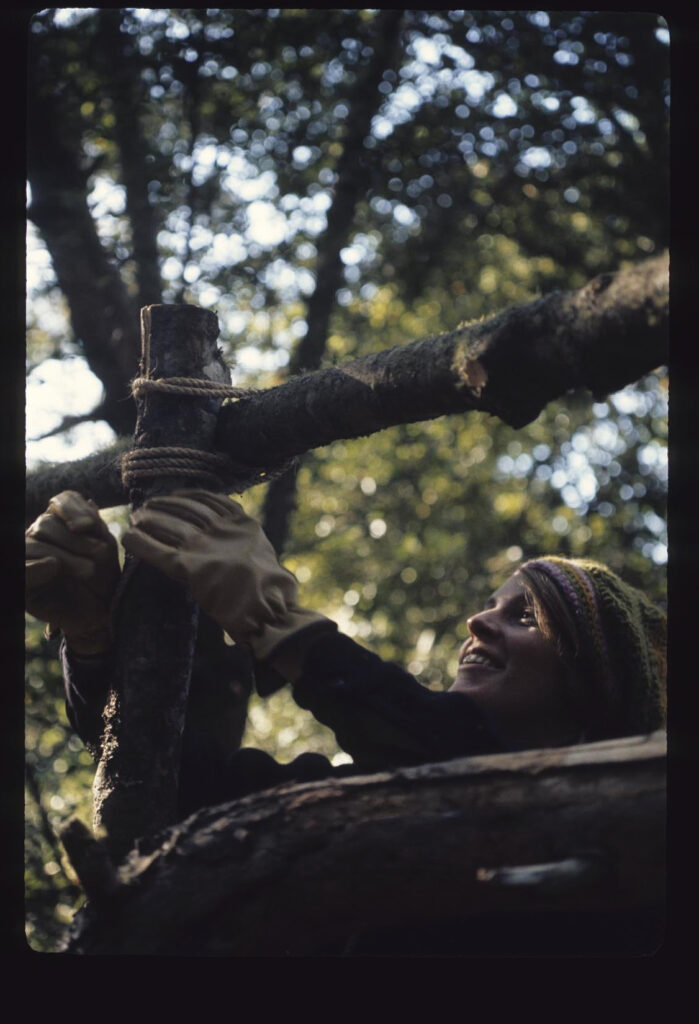

The Outlaw Builder Studio fused new modes of ecological analysis with craft building methods and ethics of land custodianship. Morning workshops conducted on site imparted the know-how needed to establish a rural foothold, including “adapting to the natural environment,” site mapping, shelter design, tool use, carpentry and wood frame construction, and “energy and waste systems.”

Guest lecturers provided additional instruction “in areas of knowledge or technique relevant to our interests.” The syllabus lists on-site talks on “Mobile Life Styles” by members of the Ant Farm art commune; graphic documentation by Gordon Ashby, an alumnus of the Eames design office and a special issue editor of the Whole Earth Catalog; material properties of wood by the sculptor J. B. Blunk; regional ecology by Gordon Onslow Ford, a former Paris surrealist and a disciple of the San Francisco Zen master Hodo Tobase; ecopsychology from wilderness-therapy advocate Robert Greenway, and “scrounging” by Doug Hall, a member of the San Francisco T. R. Uthco artists’ collective.[9]

The variety of guests and breadth of their lectures convey the expanded field of counterculture design and its heady mix of empirical, spiritual, and aesthetic enlightenment.

Acquiring building materials through scrounging rather than a cash transaction also proved transformative, imparting a new skill set that internalized abstract understandings of environmental sustainability. To make their “place in the country,” Berkeley architecture students scavenged old-growth redwood planks from chicken coops abandoned by the local poultry industry in its switch to factory farming.

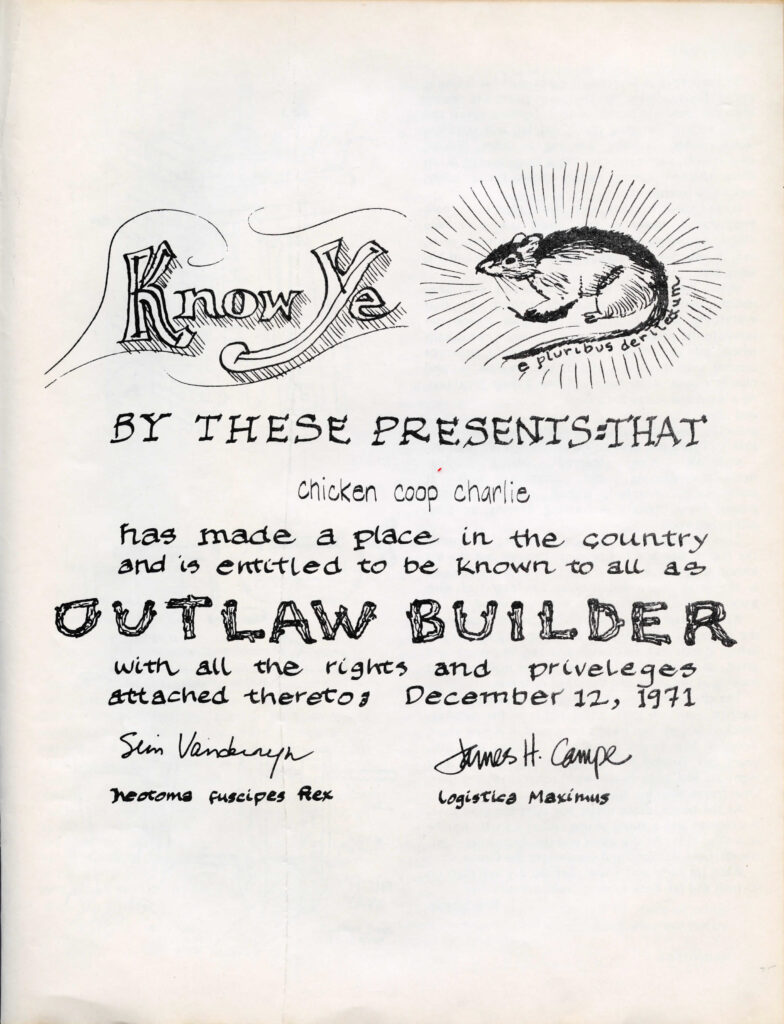

By dismantling ramshackle sheds, scraping chicken shit from salvaged wood, and trucking the hard-won gleanings back to camp, each student earned a new nom de guerre – “Chickencoop Charlie” being one example – celebrated with certificates entitling holders “to be known to all as an outlaw builder, with all the rights and privileges attached thereto.”[10] The “outlaw” moniker was no joke: Nothing that the students built conformed to code requirements or had been granted a building permit.

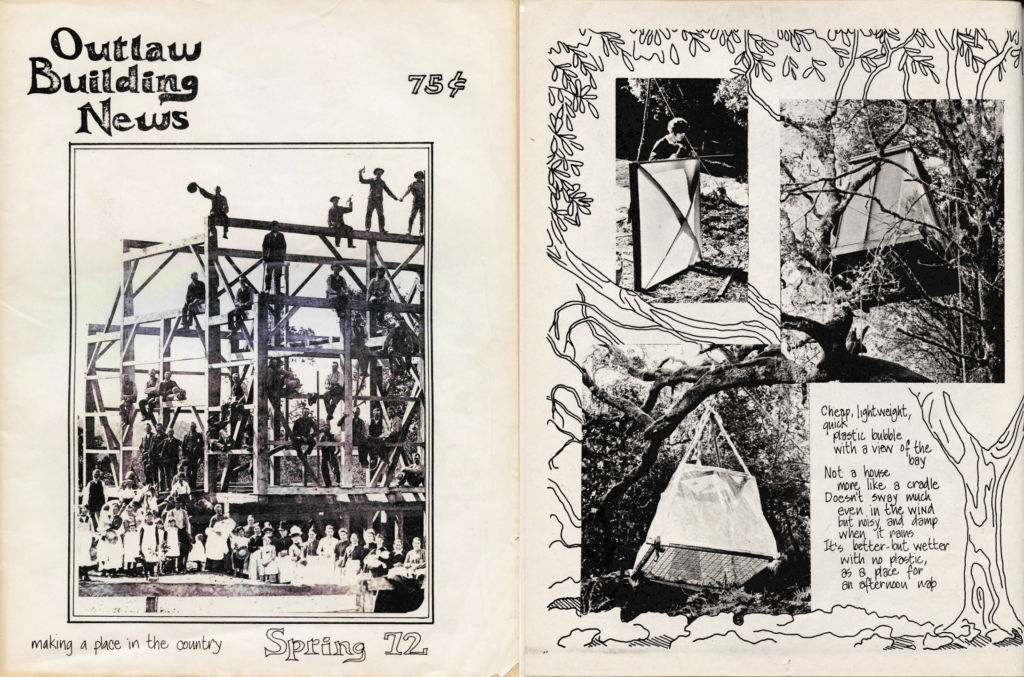

Students constructed a DIY village around “the Ark,” a workshop and drafting studio that also served as a communal dining room. Surrounding it, personal sleeping cabins, a sauna, a cookhouse, an outdoor oven, collective shower facilities, a composting outhouse, and a self-composting chicken coop sprang up over the course of the academic year. At the end of the school year, Arch 102ABC students produced a jointly authored final report on the experimental studio in the form of an underground publication, Outlaw Building News, that sold out as fast as it could be printed. Assessing her hippie apprenticeship, a participant wrote: “This … was the first in 13 years of school where community and environment were not contradicted but constructed.”[11] It was a “life architecture class,” reflected another, an opportunity to “build a house in which my physical self could exist and … a consciousness in which my spiritual self could exist.”[12]

The studio’s idyllic setting and principles struck some as escapist: “My social conscience tells me that I’m playing elitist games,” commented another outlaw builder.[13] “We share some belief in what we are doing as a way to learn about ourselves and about building,” Van der Ryn reflected. “We shared few explicit esthetics except perhaps a common regard for the land and a desire to use as many salvaged and native materials as possible.”[14] Mixing formal instruction in scrounging, DIY building, hippie nomadics, and eco-metaphysics with a blithe disregard for zoning regulations and building codes, “Making a Place in the Country” epitomized the kind of “distribution of the sensible” associated with the concept of dissensus developed by philosopher Jacques Rancière.[15]

The rural studio organized by Van der Ryn and Campe advanced a foundational critique of work practices within the design and building professions. Although it remained untheorized in the text of Outlaw Building News, the proposal for an alternative ethos of architectural labor appeared on the front cover of the student publication. It features a historical photograph commemorating a barn raising, with women and children seen clustered at the base of the heavy timber frame and proud craftsmen waving hats and tools while balancing precariously above.

A voluntaristic building tradition now practiced primarily by Old Order Mennonite and Amish communities (and even there with ever-decreasing frequency), communal barn raising was widespread in 19th-century agrarian America when many hands were necessary to build a house and skilled tradesmen largely unavailable.

The most experienced neighbors led the crew, with others following their lead, learning to build in the process. Labor was rewarded not in cash, but through reciprocity: Participants knew that when they in turn needed to build, locals would rally to their aid. As a mode of communitarian work separate from the wage labor economy, barn raising also offered the pleasures of a social gathering. The Amish call this kind of work, which serves both sociable and practical ends, a “frolic” – as apt a term as any for counterculture self-building pursuits. The outlaw builders’ invocation of an Amish tradition can be dismissed, of course, as cultural misappropriation: a defamatory trope as common and as misleading as that of the “lazy hippie.” Alternatively, retrieving a visual document of a self-build legacy that spurned commodified labor and proprietary skills can be seen in another way – as an attempt to identify a “usable past,” the term coined by the American literary critic Van Wyck Brooks to distinguish antecedent efforts capable of informing radical thought and action in the here and now.[16]

In their quest to define the communities of a sustainable society and their modes of “right livelihood,” counterculture self-builders ranged across time, evaluating archaic pasts and pharmacological futures for their utility as tools of resistance. Their records of achievement and DIY ideology are similarly available to us today, should we ever need them for our own contemporary projects of self-reinvention.

is a professor of architectural history at the University of California at Berkeley with research interests in 20th-century building cultures. He was the guest curator for the installation of Hippie Modernism: The Search for Utopia at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive and a contributor to the exhibition catalog. His current research examines the legacy of the San Francisco Bay Area as a cradle of alternative design and building practices and the role of the 20th-century American model home as a prototyping instrument for speculative material cultures and lifestyles.