Crafting the future from the past – educational concepts in the Weimar Republic

The history of fine and applied art education—at least from the 19th century onwards—has been one of continuous crisis and reform. The alternatives to education in the traditional art academies included schools of arts and crafts in particular, which were to be given various designations and names over the years. These institutions were expected to both re-establish a closer connection between art and life—an idea common to the Jugendstil movement too—and build alliances with industry, the aim being to make their products (primarily household objects) more appealing.

From 1900 to 1930, the European initiatives to reform art institutions peaked in schools such as the Bauhaus, to cite one of the most prominent—although by no means only—example.[1]

The ‘art school reform’ concept that was established in academia over the course of these developments thus refers to attempts to reform higher education in art and design from the late 19th century through to the 1920s.[2] It describes a series of developments in art and design education that also extended to the Weimar Republic. Overall, this was an international phenomenon that existed in various forms worldwide. [3]

These schools of arts and crafts were centres for the exchange and exploration of artistic ideas, for discussions about how the upcoming generation should be educated to deal with future tasks, the nature of which remained to be seen. They also formed a vibrant, active network whose protagonists communicated constantly and in which both artistic and programmatic ideas circulated.

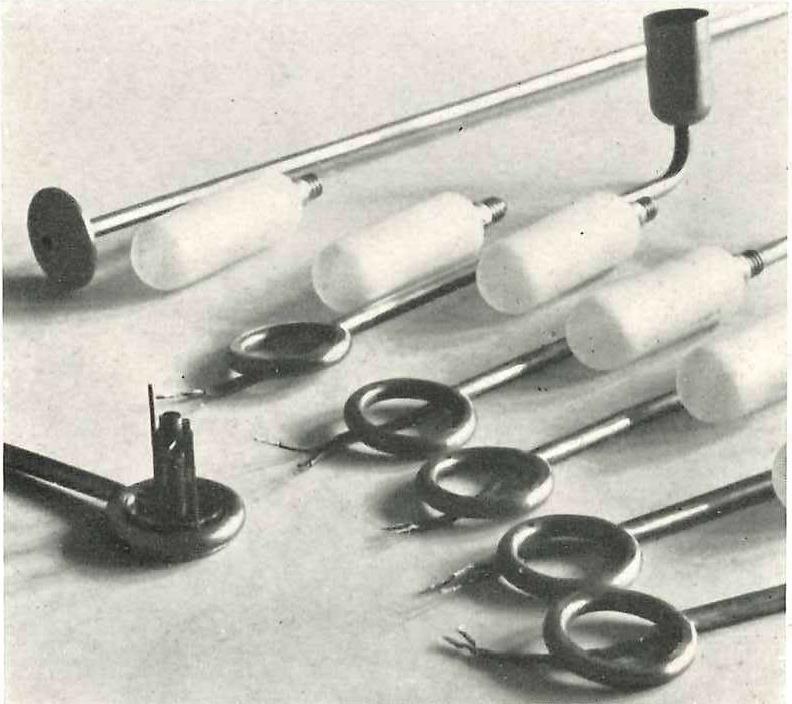

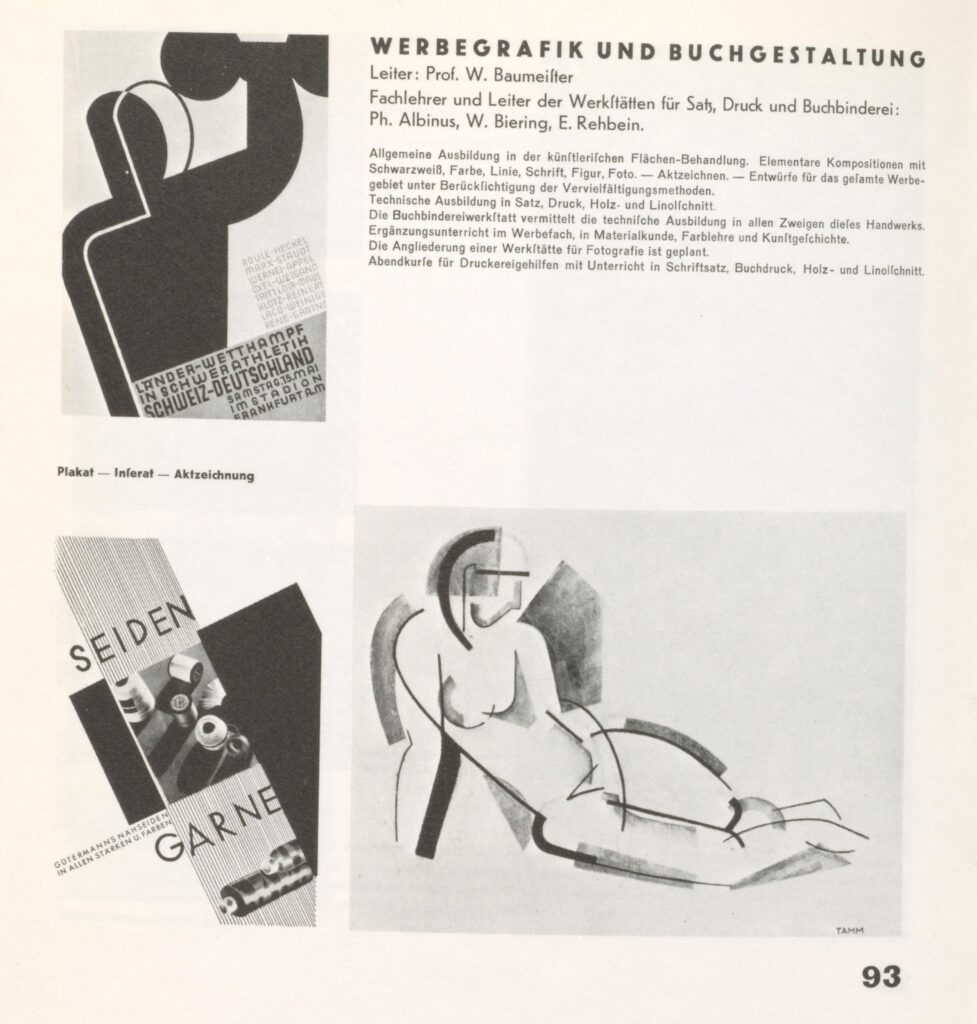

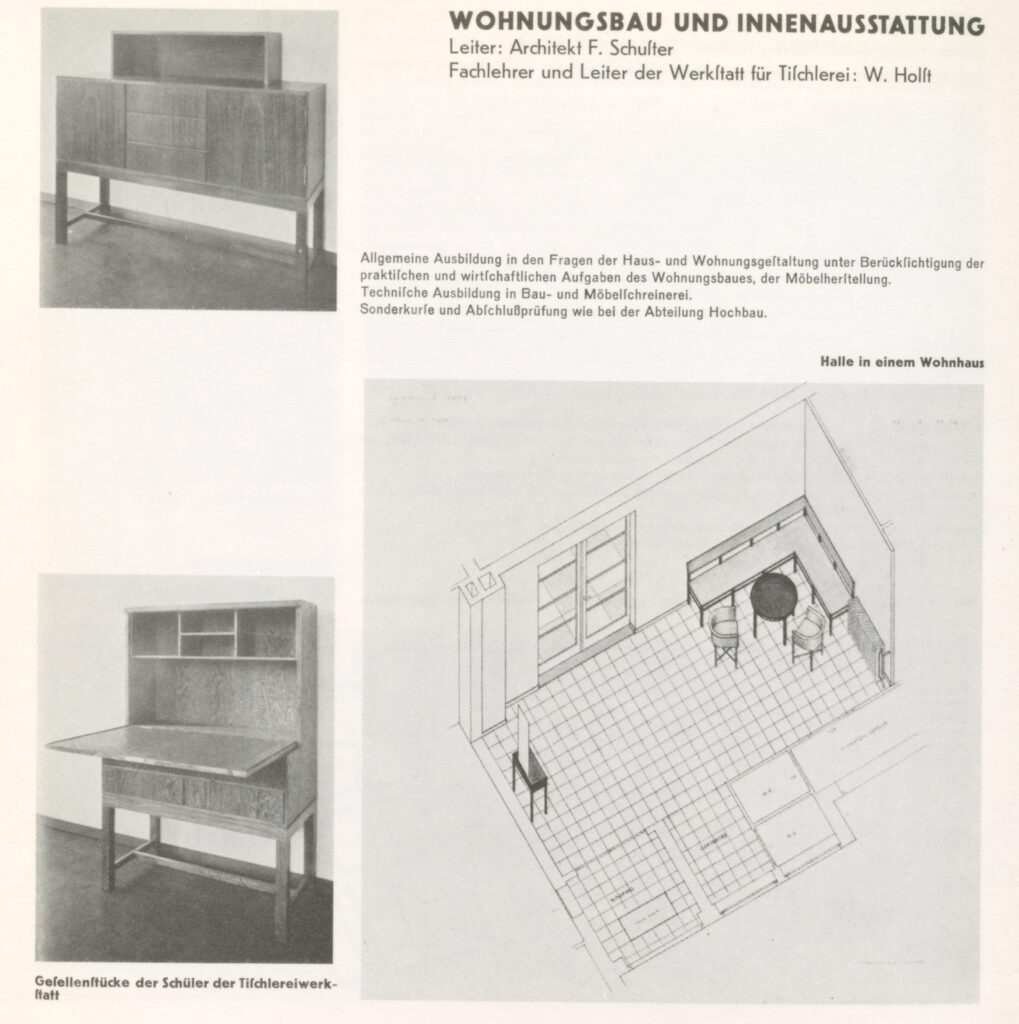

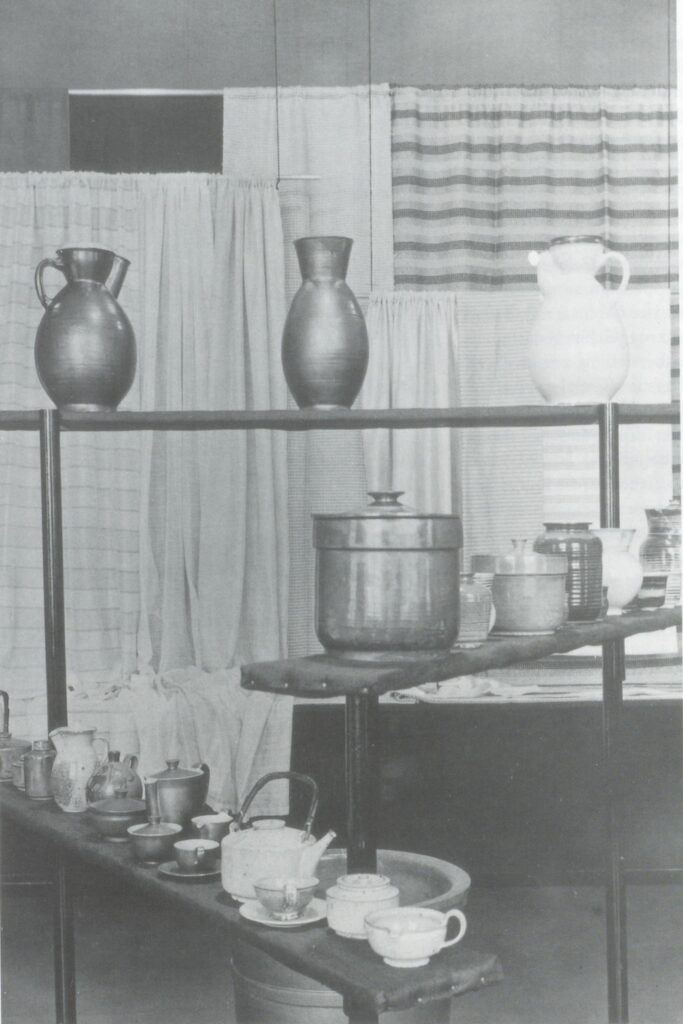

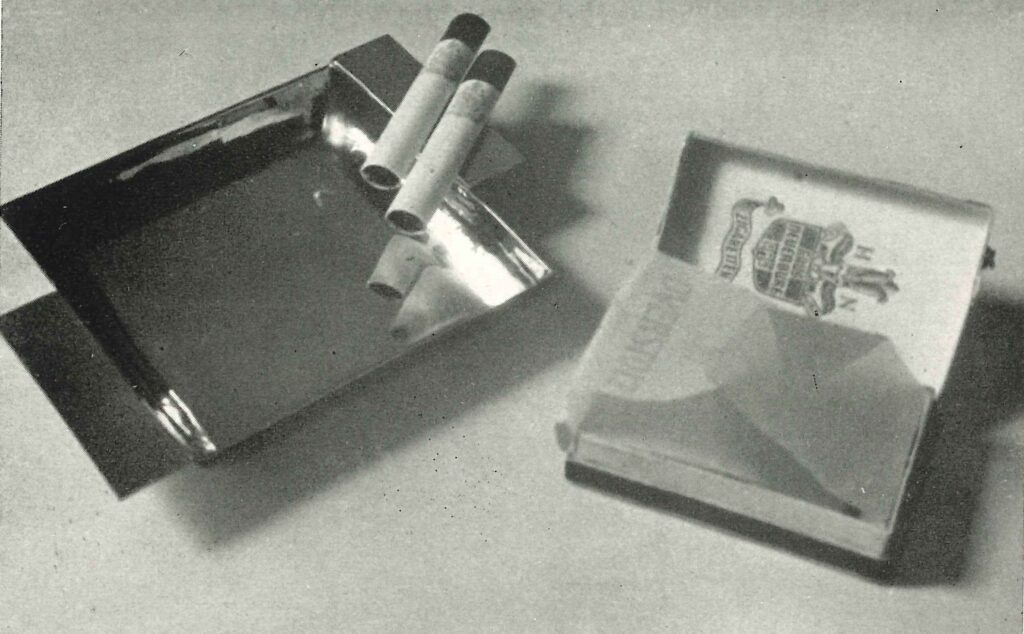

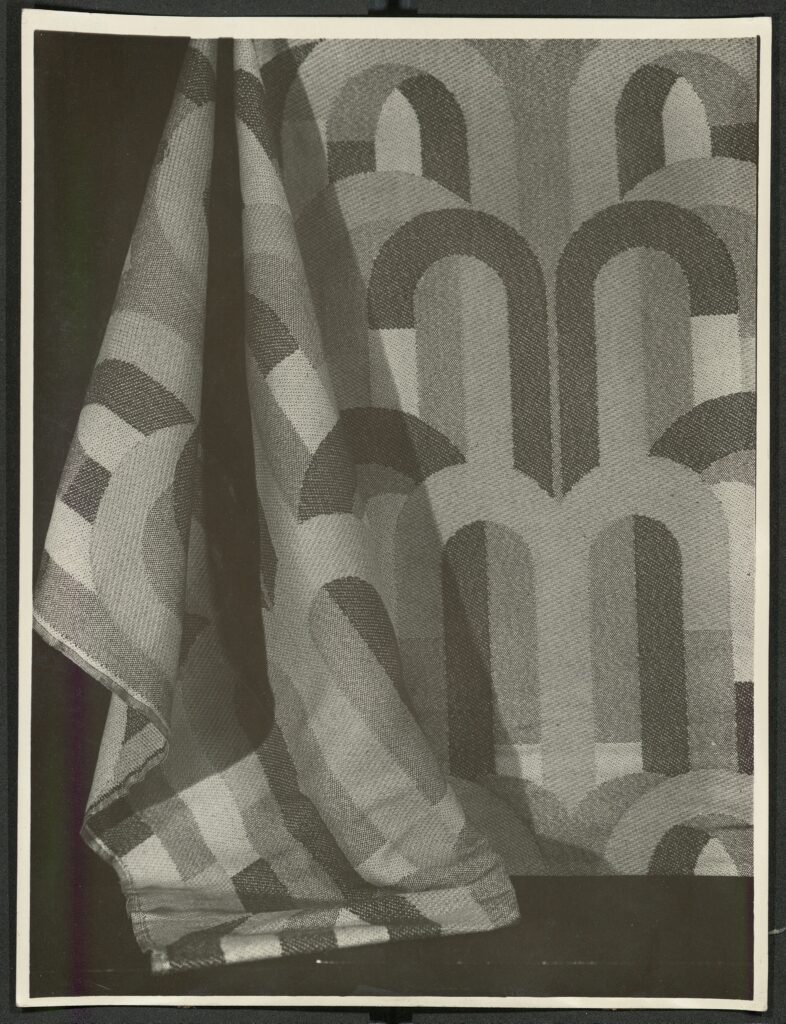

During the Weimar Republic too, these schools still set store by a fundamentally practical approach to training. Craftsmanship, regarded as the foundation of all artistic practice, became increasingly important. This often meant an insistence on apprenticeship in a workshop, usually for textiles, metal, carpentry, pottery, wall painting, printing or glass, and the students’ involvement in school partnerships with industrial enterprises and private or public commissions. Other ideas and demands associated with the art school reform included parity between the fine and applied arts, architecture as a unifying discipline and the institution of preparatory or foundation courses that strengthened the artistic element of apprenticeships. The Bauhaus stands out as the best-known of the reform-orientated schools, but other institutions had very similar agendas.

In Weimar, Berlin, Karlsruhe and Frankfurt am Main, the art academies merged with the schools of arts and crafts. Other schools of applied art established fine art courses, for instance in painting and sculpture, disciplines which previously belonged in the academies. Early examples of orientation towards the crafts include the Lehr- und Versuchswerkstätten (training and experimental workshops) directed by Bernhard Pankow in Stuttgart and the extensive establishment of workshops in Prussia in 1904 following the Lehrwerkstättenerlass (training workshop decree) drafted by architect and building official Hermann Muthesius. From the end of the 19th century, practical orientation and truth to materials had been popular concepts and remained important in the post-reform schools of the 1920s.

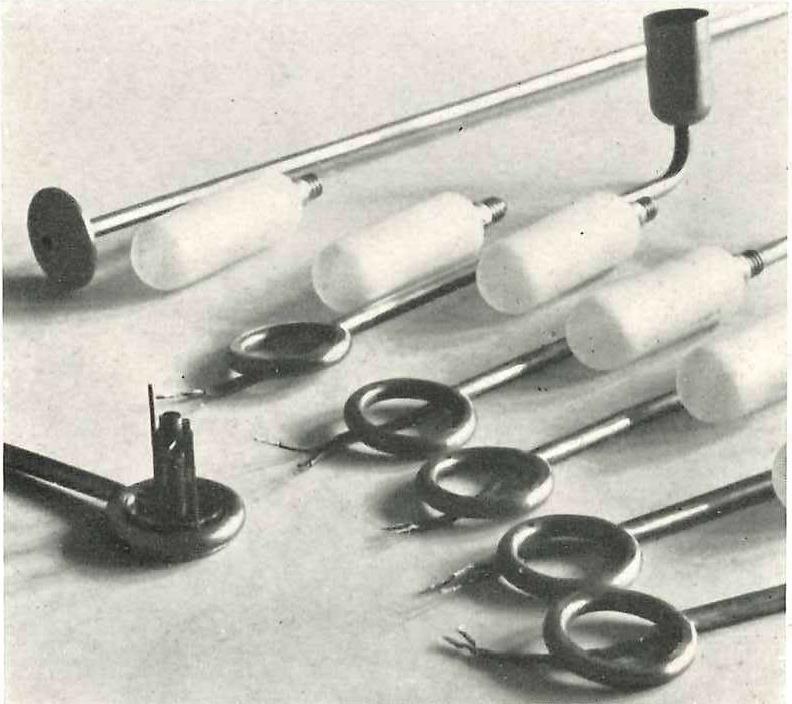

While workshop-based training still seems to make sense in the German Empire, the approach becomes increasingly questionable over time and in fact looks rather antagonistic from a contemporary perspective. Despite their focus on progress and innovation typical of the early years of the Weimar Republic, in the 1920s the reformed art schools resorted to methods that seem out of touch from today’s perspective, especially given the economic circumstances following the First World War. Although they wanted to avoid being perceived as conservative or even reactionary at all costs, in the early 1920s they regarded training in the crafts as fundamental, despite ever-increasing mass production. The selection of workshops and subjects—carpentry, metalworking, ceramics, textile techniques, letterpress printing, bookbinding, mural art, enamel, stained glass and, later, advertising and photography—and the materials associated with these strongly recall those of the 19th century schools of arts and crafts and were also largely similar in most of the post-reform schools.

However, the focus on arts and crafts (but not on craftsmanship in general) did not come about by chance. A hierarchy prevailed among the craftsmen’s trades. The lowest level was occupied by building trades such as bricklayers, plumbers or plasterers, whose work was not creative; they were in dependent employment. So-called women’s crafts like tailoring or embroidery were likewise less prestigious. More creative activities that included artistic and experimental approaches to materials and methods, in which the focus was placed on aesthetics, earned the most respect. The art and design schools thus selected artisanal subjects that were more closely connected with the higher hierarchical levels of artistic activity. By placing an emphasis on the creative aspect of the design process, craftsmanship was to lose some of the conservative connotations which it had had since industrialisation.[4]

In this way, the reformers linked their idea of a foundation in craftsmanship with art and later with technology in order to position themselves on the side of progress. For this reason, they chose craft workshops that were closely associated with the design process. And although architecture played an important role, the schools did not require future architects to learn masonry; interior design and functional objects were, however, linked with skilled craftsmanship.

The role of the workshops fluctuated during the Weimar Republic era. In the early years from 1919, they were thought to be very important. To learn a craft was to provide an artist with a livelihood. Many schools established workshops which, at the Bauhaus, at Burg Giebichenstein and to some extent at the Kölner Werkschulen (Cologne arts and crafts schools), were to bolster their finances through production. From 1923, this role was in many instances diminished when the schools shifted their focus from the workshops towards design. The foundation in craftsmanship remained important, but it became linked with a desire to more strongly integrate contemporary technical developments.

The idea of production workshops emerged and was realised with mixed results. The debate about whether workshops were for training or for production caused conflict; giving students too many repetitive tasks in the scope of production was not necessary for teaching or for profit. Craft businesses also complained about the competition from state-subsidised school workshops. In addition, practical experience alone did not necessarily lead to good design.

Changes to the workshop structure occurred only gradually; significant changes only came about through new school directors. New subjects such as advertising graphics or photography were introduced. Towards the end of the 1920s, the enthusiasm for the concept waned in many schools (Burg Giebiechenstein being one exception). Educational institutions developed a more realistic view of what workshops could do.

Over the course of this development, the separation of design and realisation, a core characteristic of industrial design, came to be seen as an effective step in teaching and in light of the design of machine-made products. From the early 1920s at the Vereinigten Staatsschulen (United state schools) in Berlin and the Kölner Werkschulen, this separation took the form of workshops for execution and parallel specialist classes in design. At Burg Giebiechenstein, design and execution were taught together in the workshops. At the Bauhaus, there was a shift from classes in the workshops to a separation of design and execution, with the workshops gradually becoming less important.

Looking at these events over time, it becomes evident that the reformed schools idealised the concept of craftsmanship and the significance of workshops. Arts school reform regarded craft as an idea, and this from the standpoint of the artist, not the practitioner.

The distinction between design and execution—typical of industrial design—had had a poor reputation since the 19th century schools of arts and crafts. It was linked with historicism, which was reviled in the 1920s, and thus with a form of design that combined ornament, form and function in a way that was later rejected—for example a design with often excessive, spurious ornamentations, laden with historical references, which often ignored the characteristics of the material. From 1919, the schools therefore first took a step backwards towards craftsmanship to which they added art.

So, while on the one hand they wanted a fresh start, on the other they clung to the pre-industrial age. Workshops remained symbols for this new beginning and served mainly educational purposes. It first had to be ascertained which skills needed to be taught for new professional fields. The schools went back to the basics only to realise that workshops alone were not enough to significantly improve industrial products.

is an art historian and science manager. From 2016 to 2022, she was a research associate at the Hochschule Hannover University of Applied Sciences and Arts, working in the field of Theory/Art and Design History. She achieved her Master’s degree in Art History in Dresden in 2012, then completed a traineeship at the Bröhan Museum in Berlin where she was subsequently employed as a project associate. She then completed a doctorate in Erfurt under Professor Patrick Rössler, titled Bauhaus in Context. A comparison of art and design schools in the Weimar Republic.