Crossing the line: the up and down (under) of craft education

In her latest publications, ‘The Politics of Global Craft’ (2025) and ‘Craft is political’ (2021), author and editor D Wood has taken an in-depth and multifaceted look at the political impact of craft traditions. In this autobiographical essay, she reflects on her educational journey in craftsmanship and polemically addresses the further development of some educational institutions responsible for craftsmanship in Canada and New Zealand. She counters the loss of significance that craft practices have suffered in the design of university curricula with a passionate plea for the appreciation of craftsmanship training.

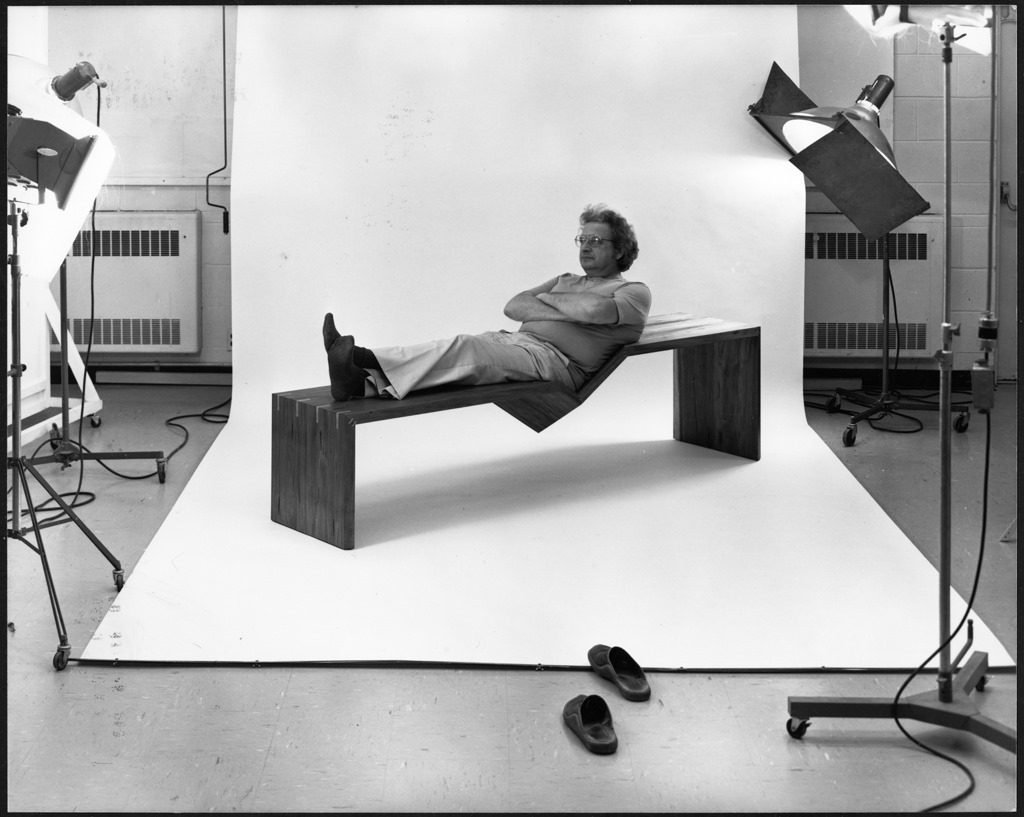

This quotation by Donald Lloyd McKinley[1] describes, in plain language, the consequence of the absence of places of craft learning. While Don said this when the craft programme he inaugurated was well-entrenched and students competed for admission, he would be dismayed – this is my assumption since he died in 1998 – by the state of craft learning today, especially at the School of Craft and Design (SOCAD) which he directed from 1967 to 1972 and where he was furniture studio master for 30 years.

Sheridan College in Ontario, Canada, was launched in 1967 with its initial divisions being technology, business, applied and visual arts as well as design. Don McKinley from the United States was appointed to head the School of Design. In addition to running the programme (Don said he didn’t run the programme, he walked it), he taught in the furniture studio, and his wife, Ruth Gowdy McKinley, a renowned ceramicist, developed the pottery curriculum. Courses in textiles, metal and jewellery were joined in 1969 by glass.

My introduction to Sheridan was in the late 1980s when I took part-time needlework design/making taught by an instructor trained in England. Like in all of SOCAD’s classes, the standard was rigorous. In 1994, I re-enrolled as a full-time textiles and furniture student. By this time, the craft studios had moved from Port Credit to Oakville, but Don was still the furniture master. I celebrated my 45th birthday as a craft student, and a fellow mature glassmaker described the experience as like being in kindergarten again – playing, being creative, learning new skills and having exposure to unfamiliar materials. I graduated with a Diploma in Crafts and Design in 1998.

My solid training in craft skills enabled me to expand my furniture knowledge at the acclaimed Rhode Island School of Design where several of my Sheridan instructors also taught. Subsequent to graduation I lectured in interior design in the United States and New Zealand and did a doctoral degree in New Zealand about studio furniture and the concurrent craft movement. My thesis was made possible by my training in Canada and the U.S., enabling me to interview over 30 craftspeople to compile a document that made a major contribution to New Zealand’s art and design history.

My thesis research,[2] undertaken from 2009 to 2012, recorded the decline of craft’s presence. The Crafts Council of New Zealand (CCNZ) was denied its government funding in 1992, resulting in the elimination of an advocate solely for the crafts: Creative New Zealand became the umbrella organisation for all the arts. During the establishment of tertiary craft education, representatives of the CCNZ had advised the Ministry of Education to provide all New Zealanders with the same opportunity: eleven craft programmes were mandated from the top of the North Island to the bottom of the South Island. However, education policy changed in 1989 so that colleges no longer had to adhere to Ministry of Education dictates. In self-determining their curricula, the majority of colleges opted for visual arts that did not require specialised teachers, equipment and classrooms.

Concurrently, primary and secondary schools abandoned hands-on classes like wood shop, cooking and sewing in favour of computers. A few programmes still exist throughout the country, but the standards and variety of craft have altered substantially, since it is easier to be ‘an artist’ than commit to Richard Sennett’s estimate of 10,000 hours to become a master craftsperson.[3]

Interestingly, Wētā Workshop, the creative home of Lord of the Rings, began in Wellington, New Zealand, in 1987, just after craft education was available in community colleges (1986 and 1987). The legendary movie franchise with its need for makers to realise its settings, costumes and props had no impact on the maintenance of craft learning and practice. The move away from hands-on curriculum to an emphasis on design and digital technology undoubtedly was beneficial to Wētā Workshop for its CGI sequences, whereas the making of stuff for the films was done by artisans whose skills were individually acquired.

Having observed the fate of craft education in New Zealand, I was shocked to hear of Sheridan College’s trajectory in late 2024. I assumed the programme was set in stone and as revered by Canadians as it was by most of those who instructed and studied there. Its crafts programme is the only one of its kind in Canada. It has maintained high-quality teaching and student output for over 50 years, and yet Sheridan has announced that there will be no student intake for SOCAD in September 2025. The consequences of this decision could be devastating. Any diminishment or elimination of the teaching of textiles, metals, furniture, ceramics or glass at Sheridan will compromise not only the sustainment of craft practice nationally but also the existence of qualified and creative instructors to pass on the handmaking skills to future generations. This is what happened in New Zealand. AI, digital printing and computer generation, in which all universities are heavily investing, will never be able to replace making and relating to others with the hand and the heart.

In preparing this paper I discovered that the status of craft at Sheridan has been irrelevant for some time. In 2017, for its 50th anniversary, the college produced a video. Except for an image of someone rolling clay (which could be taken for pastry) and a glass blower, the word craft is not mentioned, nor is anyone from the craft programme presented.[4] Further, on Sheridan’s history page, there’s this: ‘If you’ve ever watched an animated film, attended a musical, had your child enrolled at a local child care centre, visited an athletic therapist or watched a Canadian television show, Sheridan has touched your life.’[5] Sheridan has touched thousands of lives by means of craft, hereby unacknowledged by Sheridan.

I contacted Mary Vaughn, Provost and Vice President Academic at Sheridan. When asked about the suspension of craft student intake, she answered, ‘This decision was part of a broader academic prioritization process aimed at ensuring that our programs remain sustainable, high-quality, and aligned with the evolving needs of students, employers, and society. Like many institutions, we are navigating shifting enrolment patterns, constrained resources, and changing learner expectations, all of which require thoughtful and sometimes difficult decisions.’[6]

Ms Vaughn went on to say that ‘intake suspension does not constitute the closure or elimination of craft education at Sheridan.’ Rather, the college intends to consult and reflect with the internal and external community, ‘without impacting new students.’

Needless to say, consultation and reflection is a lengthy process which means that the hiatus in craft education could last years. I would also argue that needs and expectations are generated in context. The Canadian Craft Federation in its Study of the Crafts Sector in Canada (March 2024) acknowledged ‘underrecognition [sic] by government bodies, educational institutions, and funding agencies’ of the craft sector.[7] If you don’t know that something exists, you have no expectation that it might have application to you, namely that being a professional craftsperson is a satisfying, rewarding possibility. In the case of Sheridan that boasts the Emmys and Oscars of its animation graduates, the silence about the long-term value of craft skills is deafening.[8]

Craft was part of Sheridan’s initial raison d’être – affordance of non-academic, fulfilling and economically viable training that would expand career prospects for Canadians. That need still exists and is even more urgent for the future of planet Earth. It is fitting to close with the words of Don McKinley: ‘Still, no matter its reputation, a crafts school requires a lot of space and fortunately we have had administrations who believe that creative areas should be supported. These administrations have realized that crafts make a difference in people’s lives, a different difference than sports do. Every community has an arena for sports, but there aren’t as many places that show the arts. In fact, one criticism of many sports is that they end up with a loser, whereas the arts are much like a marathon, in which we celebrate each person finally crossing the line.’[9]

earned a Ph.D. in Design Studies (2012) at the University of Otago, New Zealand. Her research concerned the contemporary craft movement and handmade furniture in New Zealand. She has an M.F.A. in Furniture Design from the Rhode Island School of Design, and her profiles of craft practitioners and reviews of exhibitions and books have appeared in an international roster of publications including American Woodturner, Ceramics Monthly, Craft Research, Design Issues, Garland, Metalsmith and Surface Design. She was the editor of and contributor to Craft is political (Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2021) and The politics of global craft (Bloomsbury Visual Arts, October 2025).