Modernising tradition: Design education for artisans in the 1970s and 1980s in Colombia and Ecuador

In recent decades, debates about the place of craft within design, both historically and in the present, have rekindled interest in historical experiences, while artisanal tradition has been reinterpreted as a creative resource and as an instrument of cultural development. Within the curatorial research process for the exhibition Reverberated Bauhaus: Trans-Andean modernities in Quito and Cuenca, Ecuador, in 2024 and the dialogues that ensued with the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation questions emerged regarding how pedagogical models for artisan training in the region have been, and can be, brought into dialogue with the legacy of European modernism.

This article examines two craft-design training programmes developed in the Andean region: the First Seminar on Craft Design, organised by Artesanías de Colombia (1972), and the VI. Inter-American Course on Craft Design held by the Centro Interamericano de Artesanías y Artes Populares (CIDAP) in Ecuador (1984). The analysis is situated within a broader historical framework that includes the end of the conservative hegemony in 1930 and the onset of cultural policies under Colombia’s so-called Liberal Republic (1930–1946),[1] Ecuadorian indigenist currents in the mid‑twentieth century and modernisation policies promoted by the United States together with a collaborationist agenda within the Cold War framework.

The hypothesis advanced here is that, although both programmes inherited modernising projects that instrumentalised folklore as a national emblem, their pedagogical and methodological strategies diverged, revealing distinct views of the relationship between craft, design and cultural identity. At the same time, prevailing interpretations of these phenomena have often been framed by an overemphasis on the influence of international policies or contextual conditions, from which a single – frequently ideological – explanation has been derived.

In Colombia, during the period known as the Liberal Republic, popular culture became a key instrument in the construction of national identity. As Renán Silva notes, the state promoted a cultural policy that understood ‘the people’ as ‘childlike people’ in need of aesthetic and moral education.[2] Folklore was institutionalised as the legitimate representation of the national, filtered through academic and elite criteria. This vision sought to integrate rural and Indigenous populations into the modernisation project but did so from a paternalistic framework that established hierarchies between ‘high culture’ and popular expressions.[3] Artesanías de Colombia was created in 1964 as a mixed-ownership company dedicated to promoting the Colombian craft sector, and while its management reports do not allow us to assert a direct connection with the ideas of the first half of the Liberal Republic, they do allow us to identify it as part of a strategy for economic development and productive modernisation.[4]

In Ecuador, indigenism articulated a discourse in which craft was regarded as the repository of cultural authenticity.[5] From the mid-twentieth century onward, Ecuadorian cultural policies linked artisanal work to the preservation of Indigenous and peasant identities, granting it both symbolic and economic value. This narrative was reinforced with the creation of the CIDAP in 1975 as the result of an agreement between the Ecuadorian government and the Organization of American States (OAS), which positioned craft as a tool for regional development and for projecting an internationally distinctive cultural image.[6] Both contexts laid the groundwork for conceiving design and craft training as means to revitalise traditions while simultaneously consolidating them as a fundamental part of modern economic dynamics.

The creation of Artesanías de Colombia in 1964 responded to the need to modernise the craft sector, improve product quality and expand its presence in national and international markets. The First Seminar on Craft Design, held in Bogotá in August 1972, brought together national and international experts to reflect on design’s role in craft.[7]

Yolanda Mora, one of the lecturers at the first craft design course, endorsed the proposal to create a centre for craft design and research that would bring together designers, architects, skilled artisans and anthropologists to develop products inspired by Indigenous motifs, ‘presented according to the tastes and preferences of our time.’[8] This proposal included holding competitions for artisans, whose designs would be adapted for serial production, thereby linking individual creativity and technical skills to market criteria.

The U.S. expert David Van Dommelen[9] proposed the formation of a travelling training group in art and design, made up of specialists in industrial design, craft techniques and art education, which would travel throughout the country adapting its content to the needs of each region. This idea reflected a decentralised and flexible conception of training, in line with cultural extension programmes implemented in other countries. Designer Rómulo Polo addressed the issue of external influences, distinguishing between the ‘positive’ ones enriching production while respecting the cultural context and the ‘negative’ ones, which impose foreign styles and distort original values.

Cecilia Iregui de Holguín contributed a historical perspective, noting that Colombian craft, after having been central to daily life during the colonial period, had been relegated to marginalised sectors for more than a century, maintaining its authenticity but without benefiting from renewing influences. Her diagnosis underscored the urgency of reconnecting craft practices with new sources of design and with markets that would value their specificity.

The V. Inter-American Course on Craft Design, organised in Cuenca in 1983 by the Centro Interamericano de Artesanías y Artes Populares (CIDAP) with the support of the OAS, stands as a significant example of a comprehensive and transdisciplinary approach to craft training. Its programme included modules on popular culture, morphology, expression, archaeology and craft as well as appropriate technologies, integrating historical, aesthetic, technical and productive dimensions.

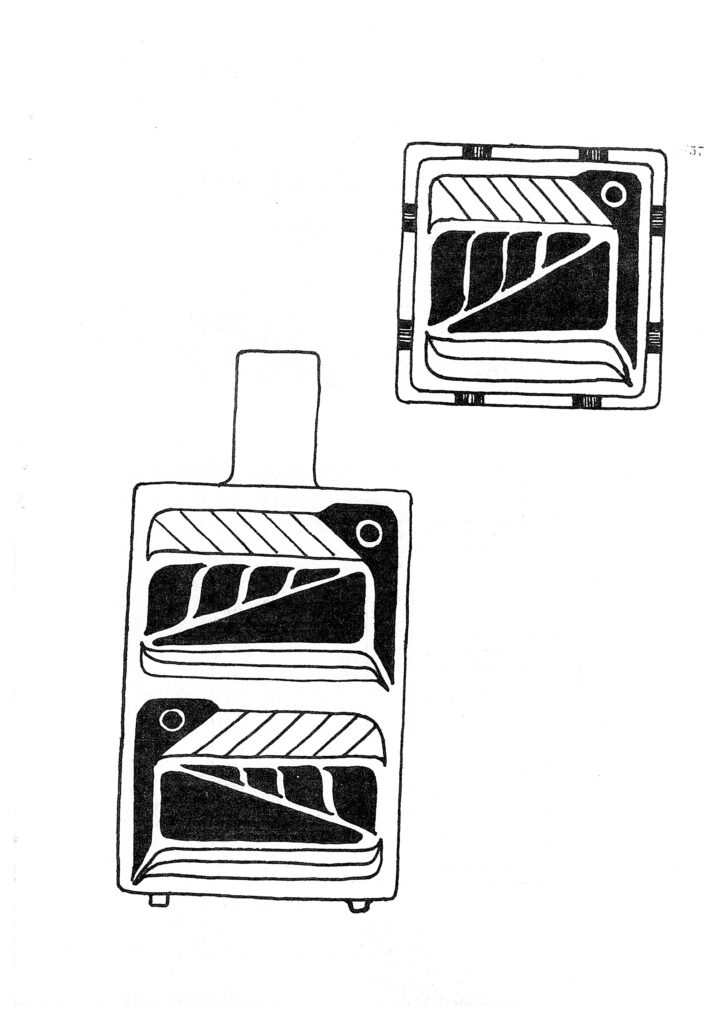

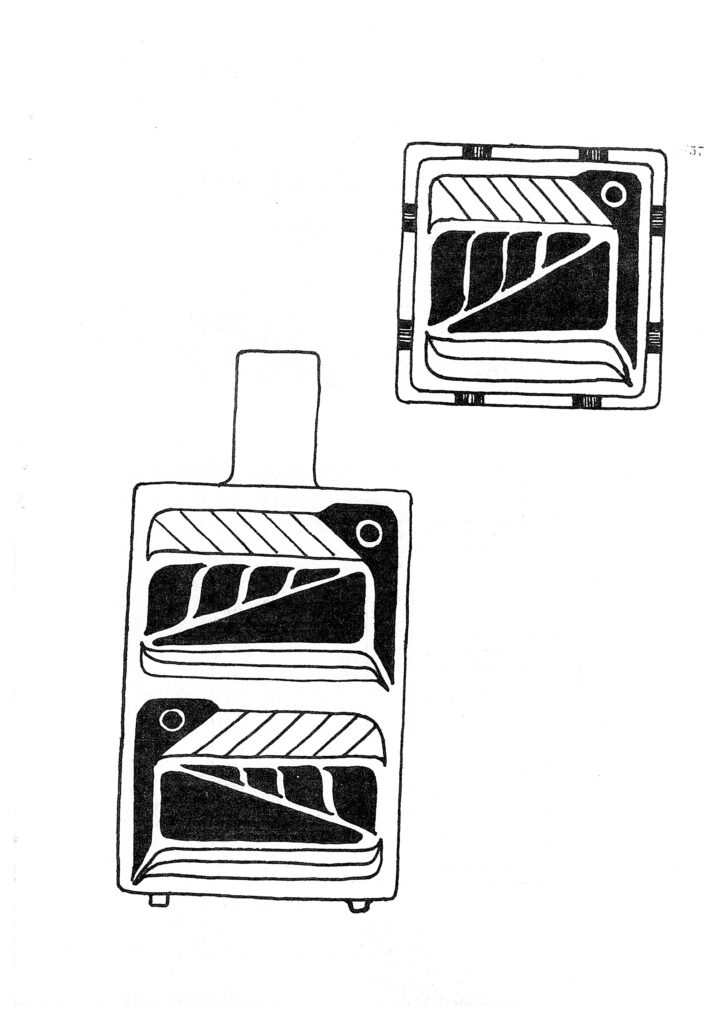

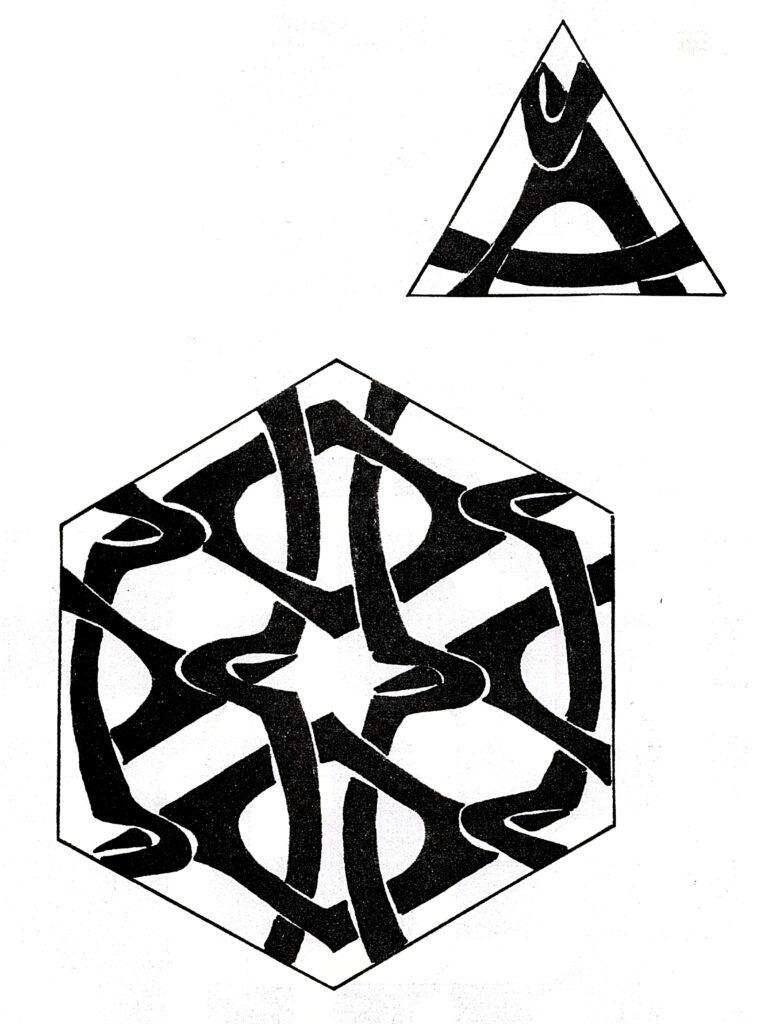

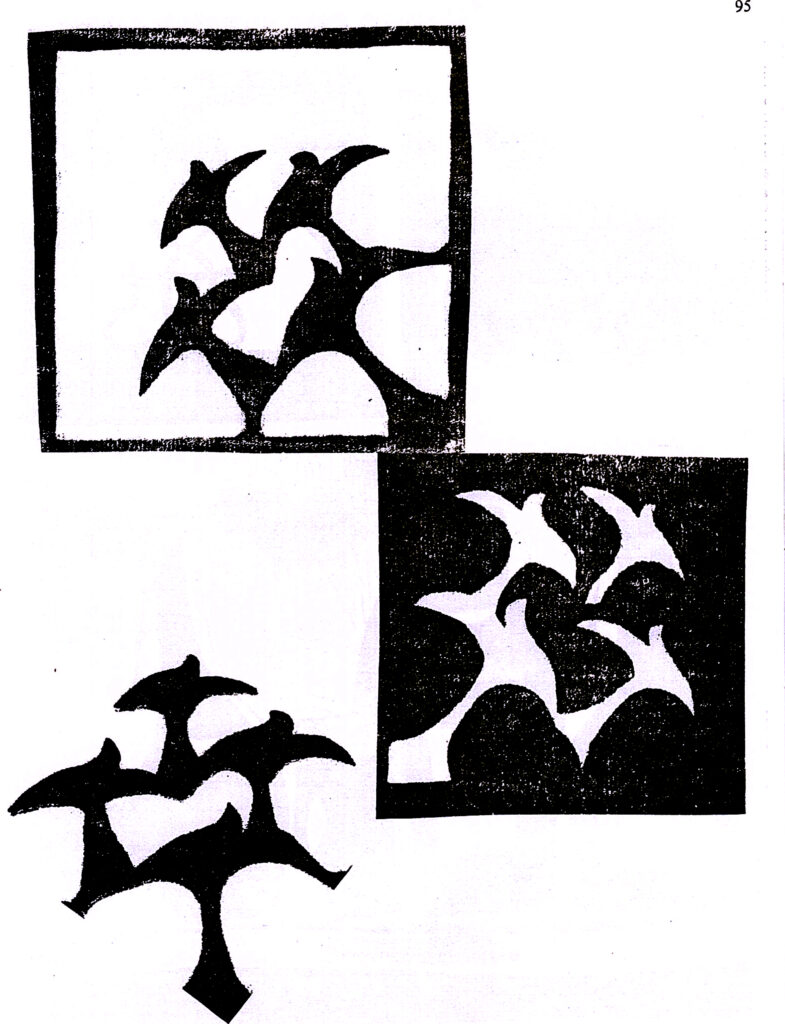

One of the course’s distinctive features was the reinterpretation of archaeological and natural motifs as triggers for formal innovation, fostering experimentation that went beyond the mere reproduction of traditional forms. The methodology incorporated fieldwork in artisan communities, encouraging direct exchange between participants and local master artisans. This practice – also applied in programmes by Artesanías de Colombia during Graciela Samper’s tenure – generated situated learning in which technical knowledge was enriched by an understanding of the social and cultural context of production.[10]

In contrast to the Colombian model of the 1970s, which was more oriented toward standardisation and quality control, CIDAP in 1983 embraced an open design approach that combined historical research, formal exploration and critical reflection of heritage. The course was conceived as a space for collective experimentation and interdisciplinary dialogue among designers, anthropologists, art historians and master artisans, marking a significant step forward in the regional pedagogical proposal.

This training cycle continued the following year with the VI. Inter-American Course on Craft Design, held in 1984 in the Argentinian province of Catamarca, under the organisation of CIDAP and the OAS, in collaboration with the Government of Catamarca and the National Arts Fund. While maintaining the interdisciplinary orientation of the Cuenca edition, the Argentine context placed greater emphasis on alignment with provincial craft development policies and on adapting products to specific markets in the Southern Cone. The event in Catamarca reinforced the role of the Inter-American Courses as regional exchange platforms where design acted as a bridge between local cultural identities and strategies for economic integration within an international framework.

The programmes shared a central objective: to improve the quality and competitiveness of craft through design training and the valorisation of traditional knowledge. In both Colombia and Ecuador, the use of Indigenous motifs was encouraged, and craft was recognised as both a resource of identity and an economic driver while also incorporating modern disciplines into the reframing of craft’s role within a national project. However, the strategies and emphases of each programme differed significantly.

In the Colombian case of 1972, the model was highly institutionalised and sought to insert craft into broader markets through processes of standardisation, quality control and specialised technical assistance. The initiative was led by state agencies and experts who, while seeking collaboration with artisans, worked within external frames of reference – initially with strong U.S. influences.

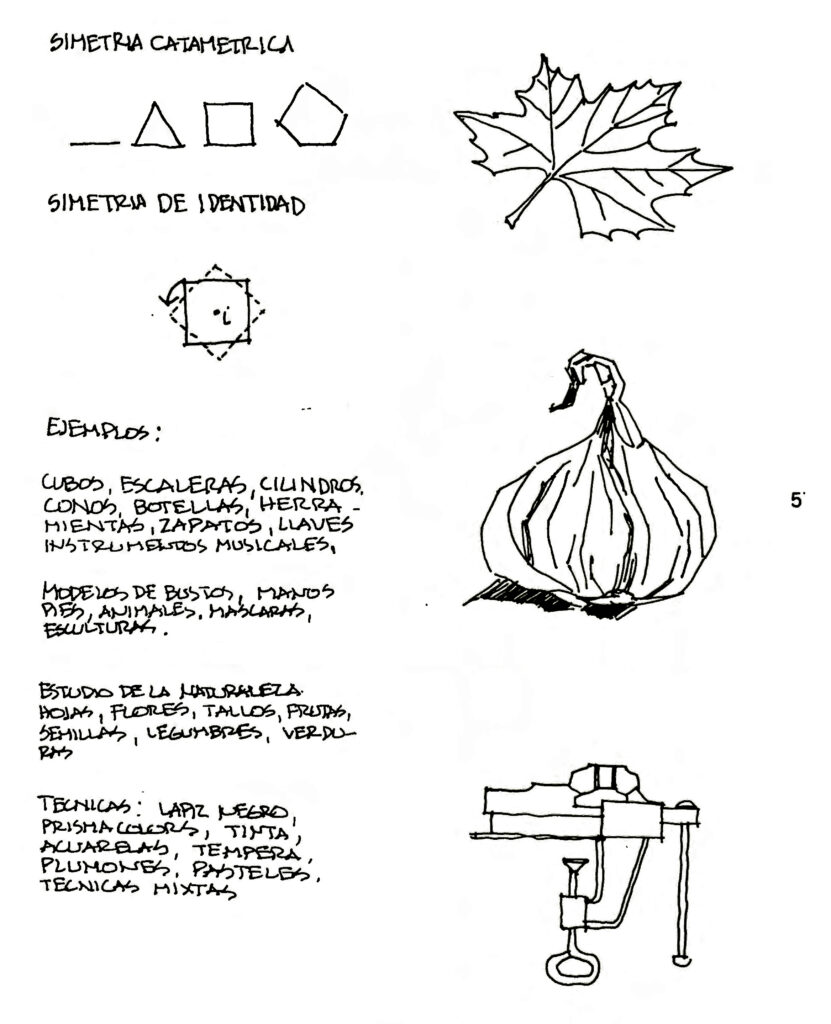

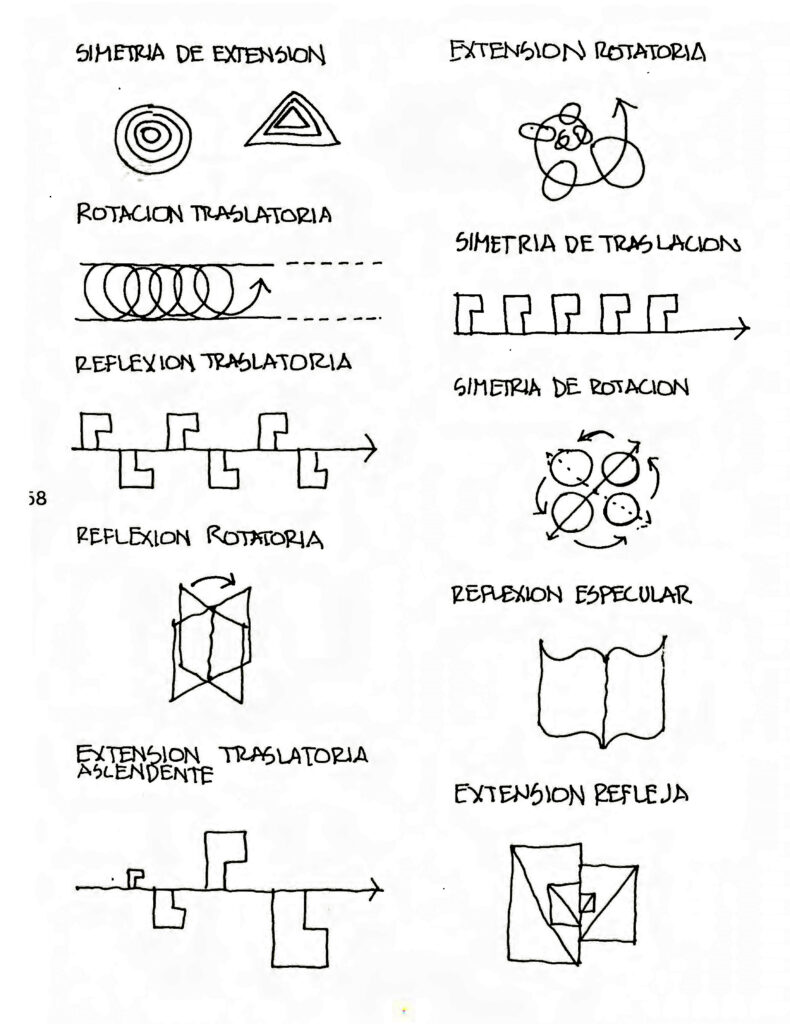

The Ecuadorian experience, represented by the V. Inter-American Course on Craft Design in Cuenca (1983) and followed by the VI. Course in Catamarca, Argentina, one year later, had a more experimental and participatory structure. The 1983 Cuenca edition combined archaeological and natural sources with immersive community methodologies, engaging artisans not only as recipients of knowledge but as co-creators in the training process. The Catamarca edition maintained this interdisciplinary orientation but gave greater weight to market adaptation and integration with regional development policies. Both experiences demonstrated a sophisticated design language for craft training, drawing on Gestalt theory, the elements and principles of design, tessellation and pattern making to expand artisans’ creative and formal repertoires.

In the late 1970s, a more participatory approach in both countries began to draw from the principles of participatory action research (PAR), introduced and adapted in Colombia by Orlando Fals Borda.[11] In Colombia, while the economically driven model dominated, certain experiences, led by figures such as Graciela Samper, Jairo Acero and Carlos Rojas, showed affinities with qualitative, PAR-type methodologies. In both contexts, the interaction between international development agendas and locally rooted critical approaches shaped a hybrid field in which craft design education oscillated between the transfer of external models and the affirmation of cultural identities.

The comparative analysis of the Colombian and Ecuadorian programmes at these two historical moments offers a snapshot of what it was like to think about craft in the Andean region before and after the intervention of governmental bodies and international cooperation agencies. While both inherited the modernising matrix of the twentieth century, their pedagogical and methodological approaches responded to different contexts and priorities, reflecting divergent realities of craft and trades. According to the sources reviewed, the Colombian case of the early 1970s is characterised by the pursuit of institutionalisation and a market-oriented approach, whereas the Ecuadorian case – exemplified by the V. Inter-American Course in Cuenca (1983) and the VI. Course in Catamarca (1984) – moved toward interdisciplinary experimentation, community immersion and regional development integration.

Nevertheless, both models engaged – almost synchronously – with the principles of participatory action research. Delving into the scope and consequences of the institutionalisation of craft design exceeds the space available in this article; however, the exhibition Reverberated Bauhaus[12] made it possible to highlight some of these processes between the 1960s and 1980s, during which class tensions emerged, revealing different conceptions of the social utility of the arts and crafts: some embedded in assistance-oriented and redemptive projects for marginalised populations, others propelled by a more progressive and de-hierarchised impulse.

The notion of folklore, latent since the 1930s, shaped the relationship between craft and the national project, often from a centralised and hierarchical perspective. It was only with the gradual adoption of qualitative and collaborative methods from PAR that it became possible to establish a framework of understanding grounded in principles of equality and social justice – one that reconfigured the place of crafts within contemporary cultural construction and offered a genuinely modern, humanist lens through which to have a fresh look at and revitalise tradition while fostering community care.[13]

is a Colombian design historian, researcher and professor at the School of Architecture and Design of the Universidad de los Andes in Bogotá. He holds a Ph.D. in Art Education with a focus on visual culture from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, an M.A. in Art History and a B.A. in Industrial Design from the Universidad Nacional de Colombia. His research explores the intersections of design history, craft, architecture and visual culture in Latin America with an emphasis on the social and political dimensions of design education. Peña has curated and co-curated major exhibitions, including Bauhaus Reverberada (Bogotá, Medellín, Quito), and he contributed to Crafting Modernity: Design in Latin America at MoMA in New York (2024). He was also co-author and a member of the editorial and research team of the renowned book Atlas histórico de Bogotá. His work bridges archival research, community engagement and critical theory to examine how design mediates cultural identity and modernisation.