Archive as a Site for Knowledge Exchange

Susanna Chung (SC), Programmes Manager and Head of Learning & Participation at Asia Art Archive and Özge Ersoy (ÖE), Public Programmes Lead at Asia Art Archive, reflect on the institution’s educational programmes and their role for its overall mission.

We met the participants of this publication through Gudskul and documenta fifteen. Asia Art Archive’s recent collaboration with Gudskul and our contribution to documenta fifteen build on our ongoing research on the role of academic and alternative pedagogy in the development of contemporary art in Asia, so it would be apt to start here.

We received ruangrupa’s invitation as part of a group of collectives focusing on education. The initial question was how we, as an art archive, could contribute to discussions about knowledge sharing in the cultural field. Asia Art Archive is a nonprofit organisation initiated in 2000 to respond to the need to document the multiple recent histories of art in this region. We have an onsite library in Hong Kong and we have a growing repository of primary source material, photographic documentation, video recordings, ephemera, and more, which we digitise and make accessible for users worldwide–they are all freely accessible on our website. These materials are related to artists who are not only creators of artworks but those who are educators, organisers, curators, or writers at the same time, so when you look at their archives, you don’t only see materials about a single artist but also changes, fluctuations, and discussions in the cultural communities they have been part of.

For our contribution to documenta fifteen, we are highlighting the work of a group of artists who are committed to preserve cultural memory through their work and pedagogy. We focus on three collective endeavours: the artists associated with the Faculty of Fine Arts in MS University of Baroda and the Living Traditions movement in post-independent India; the feminist collective Womanifesto who organised biennial events in Thailand between mid-1990s and mid-2000s; and performance artists who used everyday objects and sites, documented each other’s work, and participated in performance festivals in East and Southeast Asia, from the 1990s onward.

The title of our display, Translations, Expansions, hints at how these artists study, document, and reinterpret knowledge that is part of daily life–the vernacular and the often overlooked types of knowledge, beyond textual knowledge or what we learn at school. They absorb these forms into their work and pedagogy and pass them on to next generations in a transformed state. This is different from the traditional understanding of cultural preservation and informs the work we do as an archive: our goal is to build resources and keep activating them at the same time. This is why it’s crucial for us to engage artists, researchers, and educators to interpret our resources and promote debate around our shared research interests.

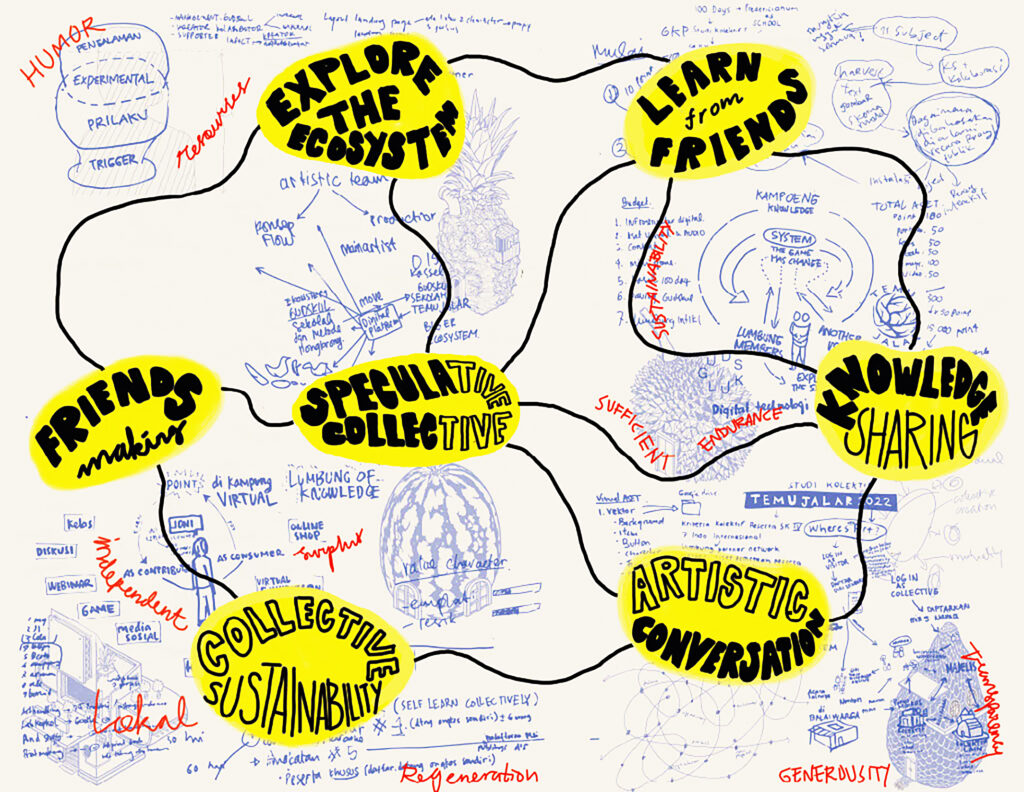

As an art archive, we contributed to documenta fifteen, an exhibition of contemporary art. Our collaboration with Gudskul–our most recent project in Hong Kong–is a way to flip this: this time, we invite contemporary art collectives to engage with an archive, most specifically with the archival resources we have on art collectives in Asia. Titled The Collective School, this project explores artist-driven, self-organised, and collective models of learning. It began with our invitation to Gudskul in 2020, who in turn invited eight collectives from across Asia to join the exhibition–they are also contributors in this publication. In the exhibition, we see their artistic responses to archival materials, such as videos, sculptures, games, and zines, which we developed together through group conversations over the past year.

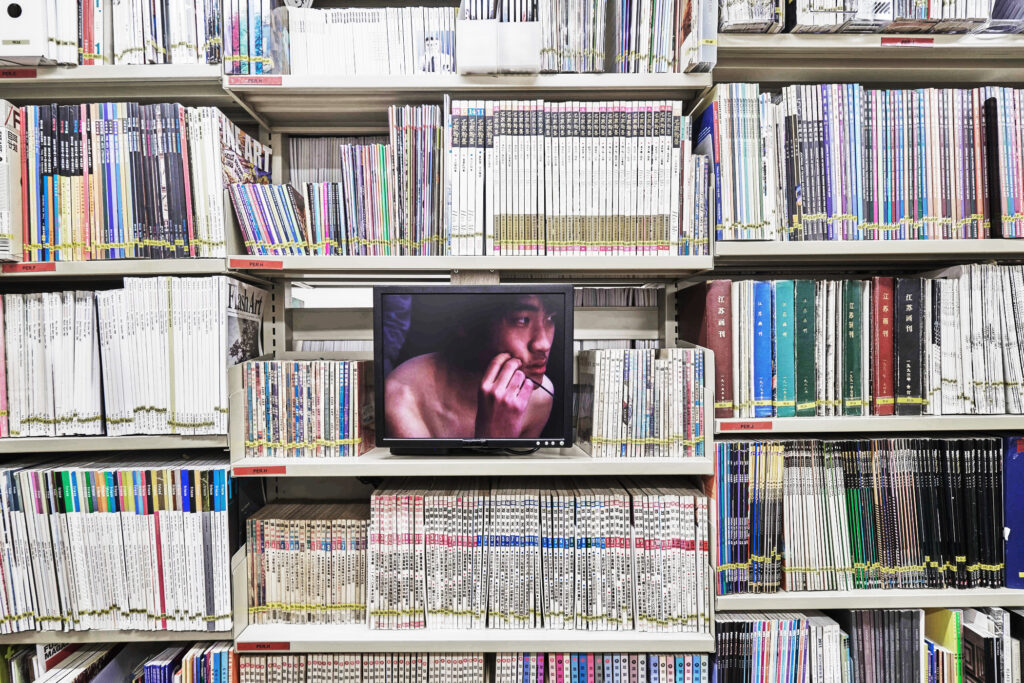

We are excited that The Collective School is the inaugural exhibition in our newly renovated library in Hong Kong. Located in a library, rather than a white cube gallery space, this exhibition also reflects our way of seeing archives and libraries as social spaces to connect people, to share and exchange knowledge. Instead of building a static archive waiting to be discovered, we actively organise exhibitions, talks, workshops around our research and urgencies in recent art in Asia.

We develop programmes to do research as well. In the past two years, I was particularly excited about Life Lessons, a series of conversations we organised with over twenty artists who teach at universities, build educational programmes at arts organisations, or run their own schools. The last conversation in the series was about school as a form of intervention. Noor Abed and Lara Khaldi spoke about the School of Intrusions, a peer-led, mobile learning platform that they co-founded in Ramallah in 2019. Ahmet Öğüt talked about the Silent University, which he initiated in 2012 as a solidarity-based knowledge exchange platform run by displaced people and forced migrants. These artist-led para-institutions make us question the potential of art institutions to address issues of social justice–distribution of opportunities and privileges. And now, with The Collective School, starting with Gudskul’s model, we discuss how a school for collectives alters our understanding of art education models that often tend to focus on individual improvement. As always, we keep learning from artists.

Here it would be interesting to speak about how we have developed AAA’s Learning and Participation (L&P), as this is a model where we learn from teachers and artist-educators.

The archive is not only a space for academic research, but also a catalyst for creative inquiry and practice. As a resource centre, we support teachers to become facilitators, develop teaching strategies to motivate students to get inspired by artists and AAA materials so as to create multi-layered works, be it artwork or writing.

L&P started in 2009, around the time of the visual art curriculum reform in Hong Kong. The reform requires students to develop a wide perspective of art across time and geographies. In order to support students to critically appreciate art in different cultural contexts, teachers have to acquire knowledge in contemporary art, which they were lacking in professional training. We wanted to respond to this practical and immediate need. When we started, none of the Hong Kong museums or independent art organisations provided this type of educational support.

We have worked with different formats, methodologies, and audiences in the last decade. For the first few years, our programmes aimed at young people aged fifteen to twenty-five. From 2012 onward, we have organised more educators’ programmes to equip them with knowledge in contemporary art. In 2017, with new contemporary art organisations entering the scene in Hong Kong with bigger teams and resources, AAA made a strategic decision to focus on teachers who can influence more students in the long run.

To support teachers, we develop programmes and online resources. For example, Teaching Labs, a series of talks and artist-led workshops, is designed to help teachers to discuss historical contexts, artistic practices, and their current needs in education. And we develop online resources along with artists, researchers, and teachers. We recently launched Open Call: Artist Exercises, an online project which brought together artist-educators and collectives from Malaysia, Philippines, India, Singapore, Indonesia, and Chinatown in Boston, to develop creative exercises for their communities of learners, connecting AAA Collections and their local context and educational environment. The participants carry out exercises with their group of learners, and put together artist exercises as Educator Resources, which are accessible online for teachers and learners in the long run.

AAA currently works with teachers from more than 250 local schools in Hong Kong, who bring their students to AAA Library to learn about contemporary art through our resources. This is a good point to speak about our communities. Hong Kong is our base and our most immediate communities–artists, educators, and researchers–are based here as well. Since the beginning of the organisation, however, we have been interested in creating a resource for contemporary art for Asia and making connections across different art scenes.

In 2004, art critic Lee Weng Choy wrote about what “Asia” might mean. He discusses “Asian” as an “adjective often characterises something as Asian in its essence” and “Asia” as a “complex, contested and constructed site.” This goes back to our name–Asia Art Archive. As a team, we are interested in looking for narratives beyond nation states, for artists who travel and contribute to different art scenes in the region, for shared and also divergent trajectories so as to contribute to a more “generous art history” as our co-founder and former executive director Claire Hsu puts it. This is why we continue to work with artists, educators, and researchers as well as like-minded organisations in a larger region. The Mobile Library Nepal is a great example of this.

Yes indeed. Mobile Library is an initiative we started in 2011. It seeks to provide foundational support to universities and independent art initiatives by activating an itinerant library through educational programmes.

Building on past editions in Vietnam, Sri Lanka and Myanmar, we recently collaborated with Siddhartha Arts Foundation on Mobile Library: Nepal to provide reading materials to artists, students, and educators in Kathmandu. The library was exhibited with modular shelves, which enabled the project to adapt to different venues, ranging from universities to independent arts spaces. It became a social space for conversation, pop-up exhibitions, workshops, research, and learning. We also developed a fellowship programme for art educators, where seven early-career art educators worked together for a year to activate the materials in the library through a series of engagements with artists in the city and youth-led workshops for their peers.

As the library occupied unique spaces and infrastructures in Kathmandu, thanks to the people who activated the library, it was able to initiate conversations with other local libraries and archives in the area as well as the wider region in Asia, which we would like to build on more in the coming years. It has been encouraging to see the regional community address challenges in contemporary art education together. We hope to continue expanding these networks of knowledge sharing and collaboration.

is an independent non-profit organization initiated in 2000 in response to the urgent need to document the multiple recent histories of art in the region and to make them accessible. With a valuable collection of material on art freely available on their website and at their Hong Kong onsite library, AAA builds tools and communities to collectively expand knowledge through research, residency, and educational programs. Part of AAA’s effort is to build a community that enriches conversations around art and function as a leading resource and catalyst for scholarship in the field. They organize exhibitions, talks, workshops, publications, conferences, symposia, and research grants for and with art professionals, educators, academics, artists, and the interested public. Generosity is at the core of what AAA does – a desire to see work shared freely, ethically, and sustainably, benefiting as many people as possible.