Decolonizing art, research, and education through participatory, interdisciplinary practices

“Salikhain” comes from the Filipino words “sali,” “saliksik,” “likha,” and “malikhain” (“participate,” “research,” “create,” and “creative.”) The name is a manifestation of the collective’s belief that art is a form of research, and that, in turn, research is also a creative process.

A collective composed of artists, researchers, environmental scientists, community workers, and educators, the name Salikhain articulates our inquiry to localize and decolonize our different practices. We desire to access the wisdom of the antidisciplinary, the social, the relational, and even the spiritual. These qualities inform our working principles: a commitment to transdisciplinarity, using participatory methods, and leveraging art’s potential to raise social capital, to communicate, and lobby policies for local communities.

Shared below are some of our activities and projects showing these principles in action.

SALI: PARTICIPATION

DECENTRALIZING AND REORGANIZING HIERARCHIES OF KNOWLEDGE1

Participatory Three-Dimensional Modeling (P3DM) was developed in the 1980s by scientists, geographers, and community workers as a method for building 3D maps with communities. In 2007, this mapping method was applied for disaster risk reduction and management (DRRM) planning by the Philippine Geographical Society.

Community-centered approach: Participatory mapping facilitators guide participants in making an accurate 3D model of a certain place. The method employs a community-centered approach wherein the participants are involved in deciding several aspects of both the mapping process and the output. Through the process of building the 3D map, participants can also improve their spatial awareness.

Exploring new materials: from styrofoam to wood: However, these 3D maps are typically made from styrofoam, rubber foam, or cardboard. Artist and woodworker Ralph Lumbres (Salikhain Kolektib) devised a method of participatory 3D modeling that uses plywood and sawdust. The resulting wooden maps are sturdier, eco-friendly, and have increased aesthetic value. The maps produced through the P3DM process devised and facilitated by Ralph Lumbres in Dingalan, Aurora (Philippines); Sulu-an Island, Guiuan (Philippines); and Hadiwarno, Pacitan (Indonesia), are the only documented P3DM maps that are made of wood.

Base map for various community data: These sturdier wooden 3D maps can be used for various purposes such as plotting different kinds of hazard data or even marking environmentally significant sites. By building wooden 3D maps, the community creates an invaluable resource – a working basis which they can continuously use to go beyond the initial data that was collected during the workshop.

SALIKSIK: RESEARCH

HARNESSING LOCAL KNOWLEDGE TO LOBBY FOR POLICY CHANGE2

Photovoice is a participatory research method that places cameras in the hands of people in a community to capture and document their observations, perceptions, and even emotions. It was first introduced as “photo novella” by Caroline Wang and Mary Ann Burris in 1994 to study public health-related issues. In this method, the photos serve as a starting point for conversation, generating a forum for communities to reach policy makers and lobby for change.

Using photovoice for integrated risk management: In the Philippines, environmental researcher Juan Miguel Torres (Salikhain Kolektib) adapted photovoice as a research method for barangay (village) disaster risk reduction and management planning. Torres’ workshop design empowers community members to collect, process, and analyze in-depth information on the capacities and vulnerabilities of their village. The approach inspires meaningful reflection on the community’s strengths and weaknesses and the collected data are then used as a supplemental document for DRRM planning.

A spotlight on small island communities: Over 7,600 islands make up the nation-archipelago of the Philippines, most of which are categorized as small islands. Due to their remoteness and geographic separation from political and economic centers, these small island communities are typically the most at risk against escalating climate hazards. One output of the photovoice workshops in Sulu-an and Homonhon Islands in Guiuan, Samar, is the successful documentation of the knowledge and good practices specific to small island communities – where people have had to rely on specific local skills, knowledge of their own environment, and existing mechanisms to survive and adapt to harsh climate conditions. Practices from these small islands may serve as models for education about disaster risk reduction in relation to managing the natural environment for larger communities as well.

Inclusive planning for persons with disabilities: Photovoice was also one of the methods used in the Lahat Dapat: Toolkit for Inclusive DRRM Planning project. The project addresses the disproportionate number of deaths and injuries among persons with disabilities during disasters. The Toolkit includes innovative and creative ways of engaging persons with disabilities in DRRM planning, ensuring that response actions of the government are aligned to their actual needs.

LIKHA: CREATION/MALIKHAIN: CREATIVE

RECLAIMING ART AS A PRACTICE IN EVERYDAY LIFE; AS AN EXPRESSION AND ARTICULATION OF LOCAL CONTEXTS3

In the participatory mapping project, Salikhain introduces the participants to the 3D modeling process through experiential learning. Before working on the 3D map itself, participants first learn basic sculptural techniques and woodworking by making relief sculptures.

Aside from being a pedagogical approach to teaching 3D modeling, the participants get to create art objects that they can keep and take home. In Sulu-an, their sculptures also become a means to express and reflect their local culture, biodiversity, and wildlife. The workshop also empowers women as they learn carpentry and using power tools. Some women made even more sculptures to create decorations for the village kindergarten.

These unique and detailed artworks express the participants’ deep knowledge of the life forms that surround them. It is a deeply embedded aspect of the epistemological violence of colonization that oftentimes we learn about (and thus yearn for) things that exist elsewhere before learning about those which are closer to us. For example, in school, we learn to read by saying “A” is for “apple” even though apples don’t grow in our tropical climate. Homes feature decor with art illustrations of hummingbirds and wild ducks that have never even been to our shores. These relief sculptures carry stories that tell of the island’s culture and daily life, small objects resisting centuries of erasure.

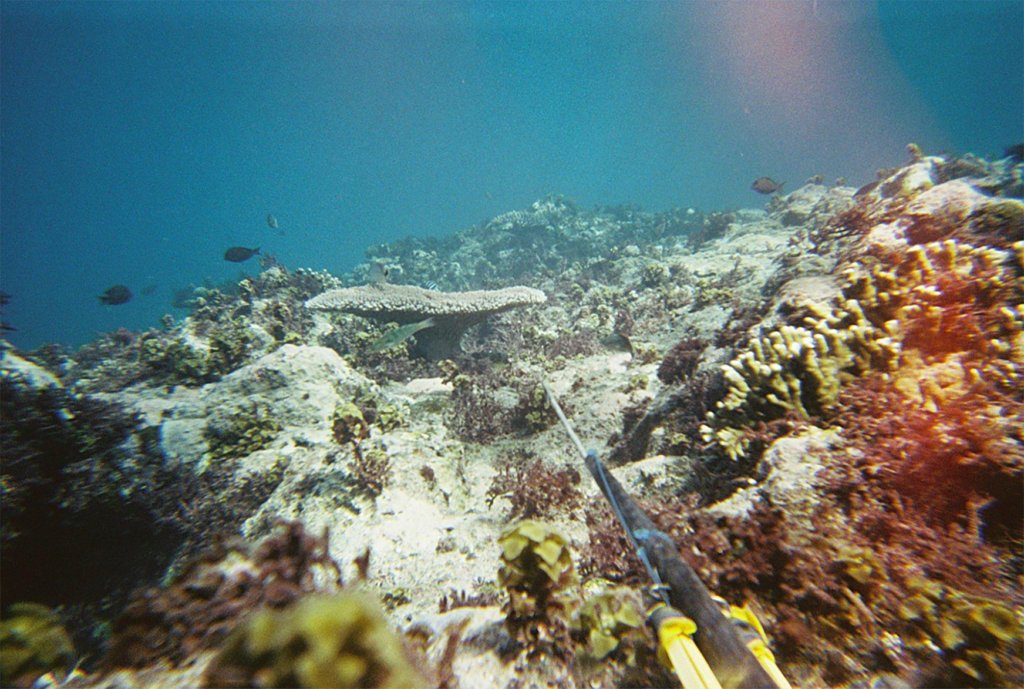

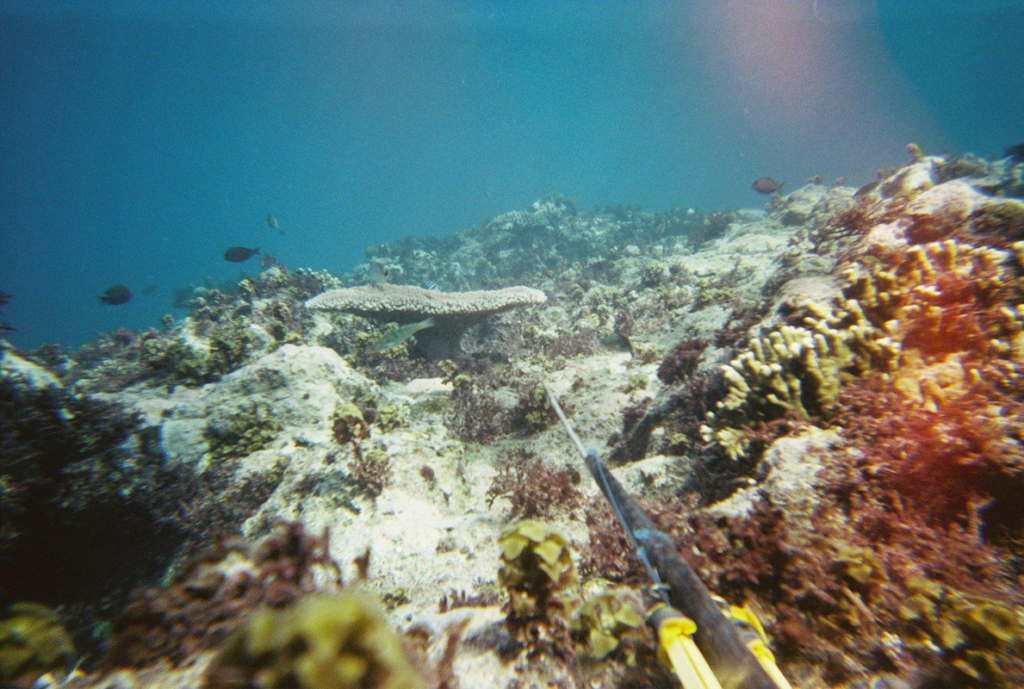

Some of the project participants in the participatory photography project in Sulu-an Island, Guiuan, Eastern Samar, were fisherfolk, local village workers, market vendors, housewives, and teachers. They were given a few weeks to a month to photograph the capacities and vulnerabilities of their villages using a disposable camera. The resulting images center the perspective from within, offering a contrast to the tourists’ gaze.

is an interdisciplinary collective based in the Philippines with a network in the Asia Pacific region. The collective integrates art, research, education, and community engagement and development into various collaborative artworks and initiatives. The common ground for the members of Salikhain is the collective’s interests in participatory art and research practices and the environment (https://www.salikhainkolektib.com).