Paradigms and Practices of PRESISI

PRESISI is a program based on a paradigm of students as independent individuals who study independently. The PRESISI program aims to provide a choice of learning models, building on a habit of critical-analytical thinking, to deal with phenomena that exist around students.

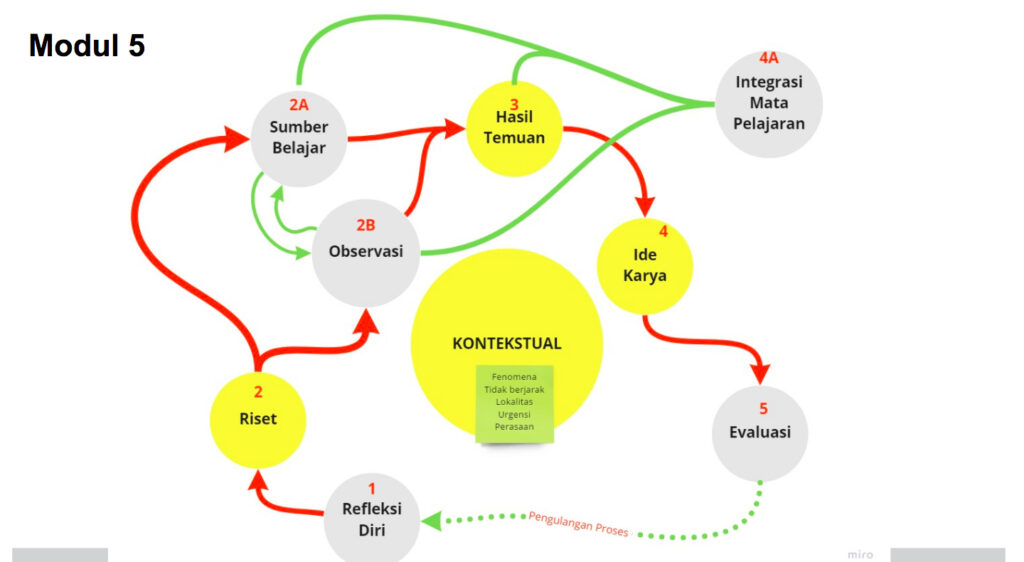

With this aim, PRESISI proposes a project-based contextual learning model, a form of learning that puts students and teachers in a position to experience direct interaction with their social and environmental situations and conditions. At the end of the process, the students will channel the outcome of their studies and the reflection on their experiences into work that is expressed through the medium of art.

PRESISI was initiated by three communities with a focus on pedagogy, namely Sanggar Anak Akar, Erudio Indonesia and Serrum-Gudskul, with support from the Directorate General of Culture of the Ministry of Education and Culture Indonesia. The program has been implemented since 2020 in 100 schools in 10 regencies and cities in various provinces of Indonesia: Aceh, Klaten, Karanganyar, Makassar, Benoa, Kukar, Maumere, Ternate, Ambon, and Jayapura.

The transcript below is a summary of viewpoints expressed during the focus group discussion OPRES SESSION #3 on “Paradigms and Practices of PRESISI,” which was held on August 22, 2022, at the Gudskul Hall.

The focus group discussion participants were Andrea Aulia Rahmat, Angga Cipta, Angga Wijaya, Aurelia Jessica Febiola, Balqis Prameswari, Dhitta Puti Sarasvati, Diah Rahmawati, Farelia Octa Viola, Hairun Nisa, Ibe Karyanto, Kaminah, Karina Adistiana, Lestia Primayanti, Moch. Hasrul, M. Sigit Budi. S, Nadila Nindyta, Wacil Wahyudi, Wiratama, and Yuli Setiawati.

PARADIGMS AND PRACTICES OF PRESISI

PRESISI is implemented in areas with specific backgrounds. For example, schools in Aceh have a background as a conflict area, schools in Eastern Indonesia too, but in addition these have the historical background of colonization by the Portuguese. These social and historical backgrounds have an impact on the dynamics of education in each of these regions.

Colonialization must be understood in the context of the hegemony of controlling consciousness through cultural works built by the colonialists. Ki Hajar Dewantara, who fought for independence, could not accept the fact that this nation is educated only with technical skills, meaning that education born from colonialism was nothing more than a teaching model to subjugate the Bumiputera so that they could meet colonial needs, both from a technocratic standpoint (mastery of administrative technology) and in the context of domination politics. The culture introduced to students at that time was born by colonial design. Thus, it is essential that, in education, students have both freedom to choose certain things, and freedom from certain things. In terms of freedom to choose, we can approach students with the PRESISI model, and they can find the meaning of independence and how to use their freedom to learn. But to have freedom from certain things means to accept the heaviest burden because the weight the students bear is constructed by the force of ideological design. If we want to give students freedom from this, we must confront those forces.

The ultimate goal is sovereignty, not just personal sovereignty, but the sovereignty of the state over its own resources, over its own knowledge. There is a lot of knowledge that is not distributed because it might be considered a nuisance to the current system. Is colonization any good? Of course, it is! For certain groups! These really hold on to that power. There is no space for democracy in colonialism. While we ourselves claim to be a democratic country, a sovereign state, we are not. It’s just that we don’t get to feel it because in its current form, colonialism is not a threat backed by weapons.

I am not aware of any history of decolonization carried out by an organization as strong as the state. Decolonization is based on people who see, feel, experience oppression. If you have a vision for a movement for change, don’t give up. This decolonization will not be carried out like colonialization, which is the product of a strong and organized power system with all its capital: organization, mass, finance, and so on. Colonialization in this new form exists and is included in the educational curriculum. Who has the knowledge? Who is in charge of that knowledge? Who has the authority to choose people in education? If the authorities are secure rulers pursuing certain interests, clearly this is a new form of colonialism in the current era.

Education is a colonial form, it is a very comfortable and romantic space. Therefore on introducing PRESISI as either a paradigm or a method in formal schools, at first it was perceived as a threat and uncomfortable. It’s uncomfortable because we often come offering freedom, freedom from systemic pressure, freedom to explore learning, but teachers see that as a threat, think it shouldn’t be like this, or don’t even know they are allowed to do that.

PRESISI is not just a learning paradigm and model. As a movement for change, it must be able to stand alone and sustain itself. This is a design that is relevant for the decolonization of education, not just once the project is completed. Colonialization is rooted in such a long history. The government, consciously or not, tends to still colonize the idea of education. Consequently, the decolonization of education will develop if the people have a strong sense of solidarity. If we want to produce relevant knowledge in keeping with the social conditions around us, we must start from the reflections of students on their social conditions and in the context of those conditions. They must be able to identify what may be a concern for the community and find a way and means to express those concerns.

Western educational design likes to categorize things, so in Indonesia there are excellent schools, best schools, favorite schools, etc.

Schools only provide knowledge that is relevant to capitalism, the point of which is to perpetuate it.

We have the phenomenon of schools being labeled the best schools and elite schools with only certain people being privileged enough to be able to go there. The standard is very similar to that of the colonial system because there is a gap between the community who have these privileges and those who do not have the necessary financial means.

In elementary, middle, and high school, I went to school and followed all the teachers’ orders, receiving lessons from the same book, with uniform learning methods. The teachers measured intelligence only according to certain abilities, such as exact knowledge. All the students had to understand the subjects without exception, get high scores to progress to the next school. The selection of a high school is based on economic capacity. If you come from a family that is economically capable, you can become a high school student. If you can’t afford it, then you must choose a cheap private vocational school or pesantren, an Islamic boarding school, in the hope that, when you graduate, you can help the family’s economic life by directly working.

Students majoring in mathematics are taught based on mathematical theory. Of course, almost all the theory comes from the West. The question is: What happens when you are free to teach anything? Can we use our knowledge for a bigger purpose, for example towards a fairer world? We can teach numbers, fractions, but when we asked, for example, “How do farmers use mathematical reasoning for farming activities?” it became clear that we don’t necessarily know the answer.

Teachers are no longer the center point of learning resources, but also act as facilitators, mediators, and mentors. PRESISI also involves the surrounding environment as a study partner. Thus, there are no more students who are ranked first or superior. Based on that, how can students develop their potential and their environment so that both can grow together?

PRESISI aims to encourage student and teachers to inquire and to question things that are not appropriate and not liberating, for example to question everything about the curriculum, the administration, and more.

Teachers and students finally found out for themselves, “Oh, this is what freedom means!” It didn’t make them feel comfortable right away, they had to approach it and try it out slowly. Schools that have been implementing this method for two or three years are also still exploring true independence and creating a new system according to the relevance of their lives as schools in the community.

is an art and education study group in Jakarta established in 2006. The word Serrum comes from the words, “share” and “room,” which signifies “sharing room.” Serrum focuses itself on educational, socio-political and urban issues with educative and artistic presentational approach. Serrum’s activities covers a wide array of ventures such as, art project, exhibition, workshop, creative discussion and propaganda. Serrum’s medium are video, mural, graphic, comic and installation art.