Products for people: Design and the discourse of development

The idea of ‘development’ has preoccupied designers in India since the inception of the discipline of design in higher education in the 1960s. In the early decades after independence, the government of India played a powerful role in the life of its citizens to provide a better standard of living. But how was this discourse of national ‘good’ refracted through the lens of design practice? Or, to put it another way, how did designers make these imaginaries ‘real’ for themselves and for those they sought to influence through their practice?

As early as 1958, American designers Charles and Ray Eames asked in their India Report: ‘There is much discussion, in India, about Standards of Living. To what degree is snobbery and pretension linked with standard of living? How much pretension can a young Republic afford? What does India ultimately desire? What do Indians desire for themselves and for India?’[1] So what did Indian designers want for the new republic?

This early phase reminds us that the exigencies of Cold War diplomacy played a key role in bringing particular ideas of good design to India. The Eames’s visit was sponsored by the Ford Foundation, which also funded the tour in India of the MoMA exhibition entitled ‘Design Today in America and Europe’. The exhibition consisted of furniture and consumer products selected “to bring to the attention of the Indian public the aesthetic values of the west in largely machine-made, mass produced objects” and to “provide an inspiration to Indian manufacturers and craftsmen for a solution to the many new problems that confront them.”[2] The foundation also supported the training of the National Institute of Design’s (NID) early faculty members in Europe, leading to curricula and pedagogies adapted from the Bauhaus, Basel and Ulm schools of design, which were echoed in the Industrial Design Centre (IDC) as well.

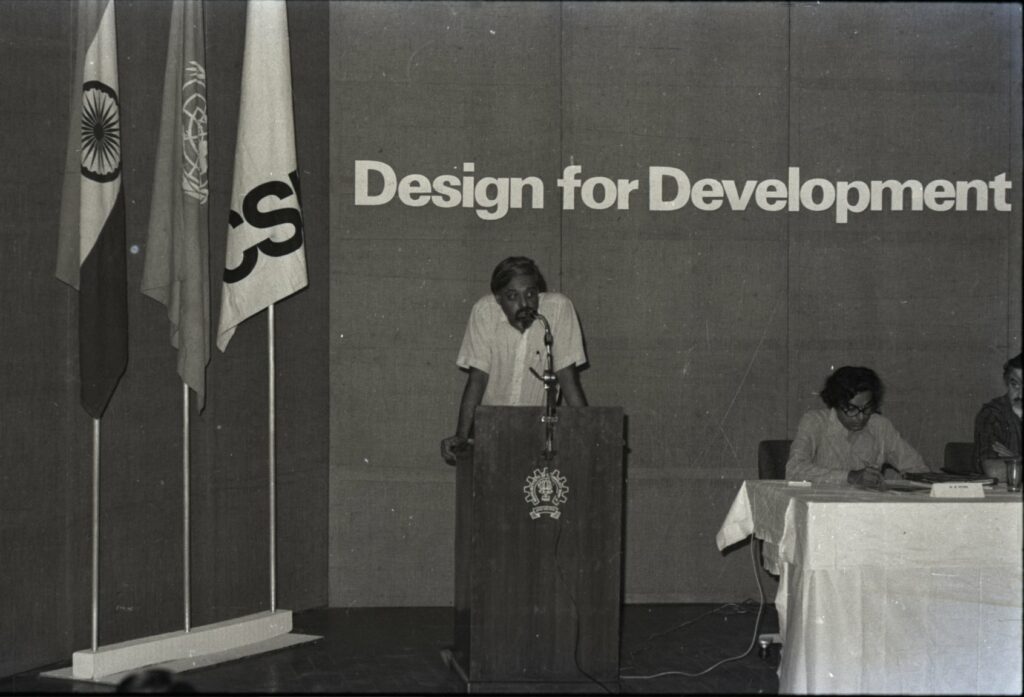

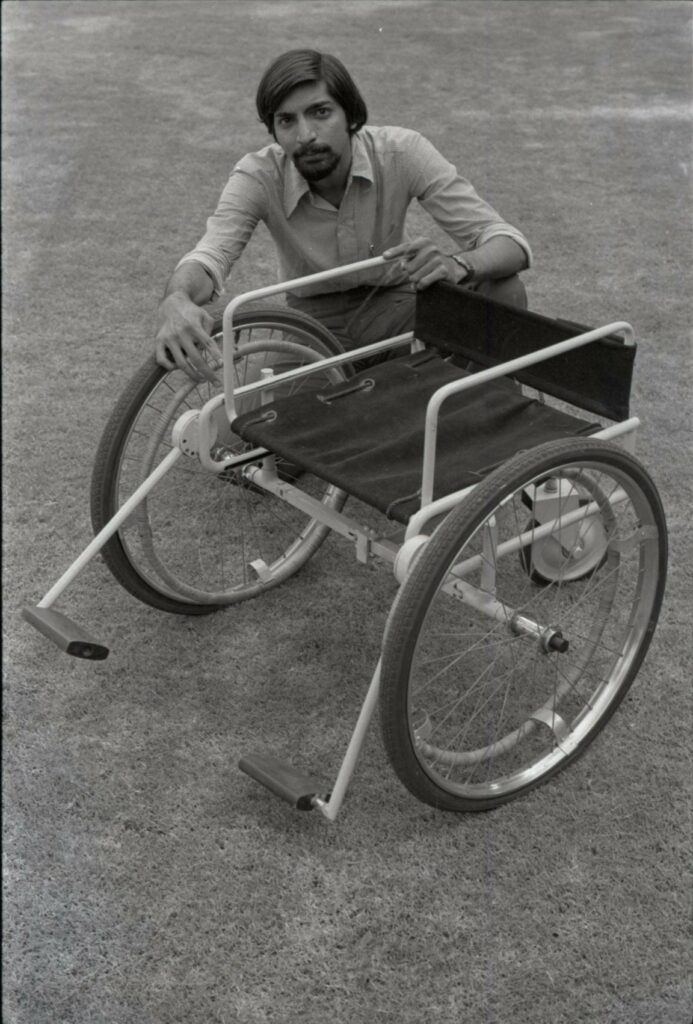

Two decades later, a decisive answer to the Eames’s questions emerged in the form of 13 case studies presented at the 1979 UNIDO-ICSID (United Nations Industrial Development Organization/International Council of Societies of Industrial Design) ‘Design for Development’ conference at Ahmedabad and Bombay (now Mumbai). Designed mostly by faculty members of the two host institutions, the NID, Ahmedabad, and the IDC, Bombay, the products ranged from the bicycle to farm equipment, from the wheelchair and post box to type designs in Indian languages, and from power tools and safety equipment for miners to latrines and craft interventions.

The professional practice at IDC and NID, exemplified by the case studies curated for the conference, shows us how faculty members were thinking about and responding to the reality that decolonization had taken place in a pluralistic and largely rural society with long and continuous handicraft traditions and small-scale industrial manufacturing capabilities, as well as distinct cultural practices. In each case study, though only a few are discussed here, the product is viewed as not only a functional or aesthetic offering but also as a cultural intervention to address social conditions. Examined more closely, the products point to an emerging set of design ethics committed to ideas of dignity, safety and well-being of Indian people.

In March 1977, newspapers reported that several farm workers – men, women and young people – were admitted to hospital in the north Indian town of Hissar. Their hands had been cut off while threshing the winter harvest. The short threshing season and the urgency of getting produce to the market speedily had led to the farming community to dismantle safety features, leading to a ‘tragic confrontation between men and machines’.[3] Moved by the newspaper report, the NID contacted the reporter and the Ministry of Agriculture, leading to the design of safer power threshers (Case 3 – Design for Safety: Power threshers – A harvest of suffering). The engagement with rural life and the suo moto recognition of a space for design intervention underlines the ‘social, cultural and political factors that influence the selection and way of solving the design problems’[4] (author’s emphasis). This is echoed in the design of safety devices for miners (Case 4 – Design for Human Factors: Miners’ safety devices) which describes how protective gear needs to take into account the physical discomfort caused by India’s hot temperatures and high humidity in the rainy season as well as miners’ cultural practice of needing to spit after chewing betel leaves and talking while working.

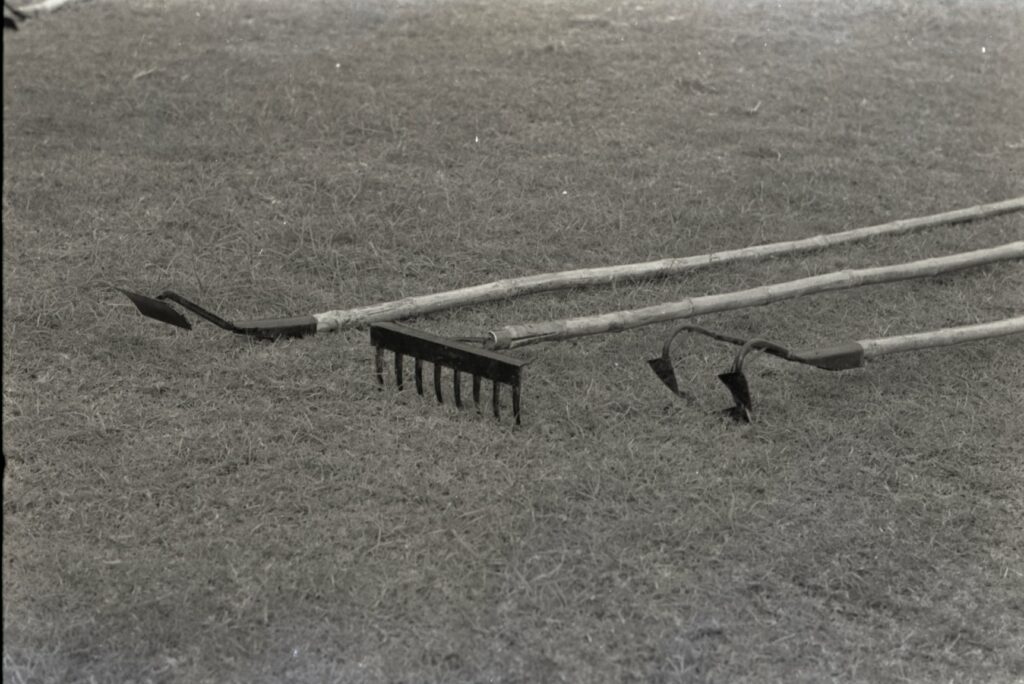

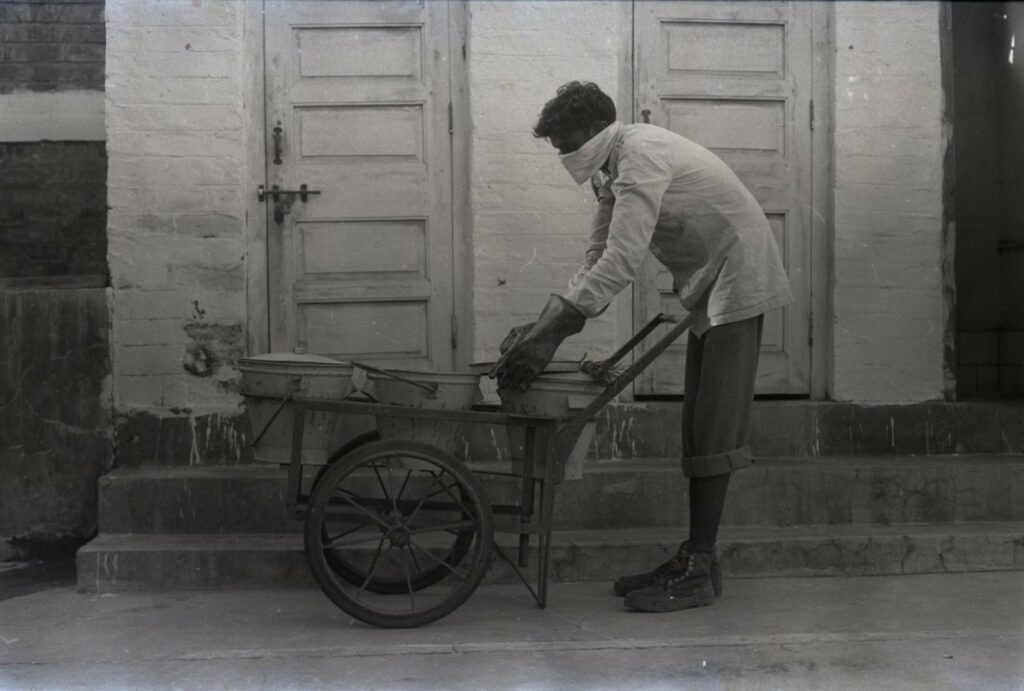

Two of the 13 case studies were contributed by community-based Gandhian organisations, suggesting that design does not take place only in design schools, nor is it practiced by professionally trained designers alone. One demonstrated improved farm implements (Case 8 – Design for Rural Technology: Farm Implements) to ameliorate fatigue and drudgery, to save labour but not to replace the labourer, which can be produced by local blacksmiths and carpenters. This is a nuanced view of product design in a country with a large population, high unemployment, and traditionally skilled communities. The other addressed a significant unsavoury aspect of India’s society, the caste system, in which one section of society is forced to manually dispose of human waste (Case 9 – Design for Human Dignity: The problem of Indian latrines). The solution is a ceramic squatting latrine that can be flushed with a minimum of water into a pit where the waste is later available as manure. Here, product design transcends functionality to become an instrument of transforming an inhuman social practice.

Castes are occupational groups and the discrimination perpetrated by the caste system is accompanied by the skills and knowledge held by each caste. In a drought-prone district in North India, textile and product designers worked with weavers and leather workers to create new products for urban markets (Case 12 – Design for Rural Progress: Learning for development at Jawaja). The tension implicit in taking these design directions is not lost on the designers or design educators. In 1977, at the ICSID conference in Dublin, the NID’s director Ashoke Chatterjee had remarked, ‘… design as we teach it may stress the needs of westernised, affluent communities in urban India, increasing their own alienation from Indian society’ and pointed to challenges that ‘demand a reappraisal of the disciplines and curricula which we imported from the west to transplant into our ancient and problematic soil’.[6] The limits of importing philosophies, pedagogies and practices from Europe and America was also well understood in IDC faculty member AG Rao’s comment: ‘The experiences in the West can only give us leads, and unless an approach appropriate to deal with the development problems rooted in social, cultural and political structures is developed, the profession would remain a white elephant.’[6]

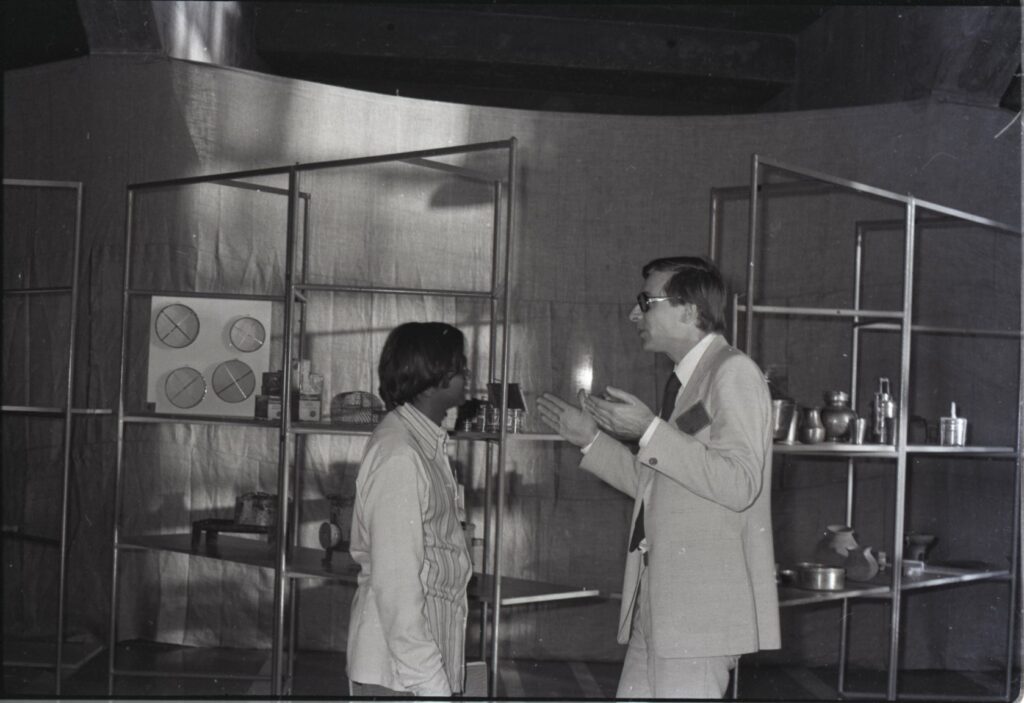

Exhibitions of Indian products were arranged at both venues. At Ahmedabad it was ‘a cross-section of products manufactured in village, small-scale, medium-scale and large industries’ illustrating ‘the skills, materials and manufacturing facilities available in our country as well as some of our more important design challenges’,[7] open to conference delegates and invited guests. At Bombay, it was a display of products designed at the IDC and a publication entitled Industrial Design Centre: A Decade of Design Experience describing these efforts was released in the presence of delegates. The IDC had earlier displayed its achievements along with the efforts of the members of the Society of Industrial designers of India in a show entitled ‘Products for People’ in order to ‘expose the public and industries to the potentialities of design’.[8] Mounted at a prominent art gallery in the city, the exhibition was seen by more than 6000 visitors.

Hosting the UNIDO-ICSID meeting and presenting the 13 case studies gave Indian designers space to engage with both local and international audiences to forge a place for design practice in the emerging postcolonial order. With some they shared a common colonial past which was responsible for their status of being ‘developing countries’ and they hoped their experiences would be of value to them all. While not explicitly pointing out the role of the developed world in the situation, the Ahmedabad Declaration on Industrial Design for Development adopted at the conference asserted that ‘designers in every part of the world must work to evolve a new value system which dissolves the disastrous divisions between the worlds of waste and want, preserves the identity of peoples and attends the priority areas of need for the vast majority of mankind’.[9]

(b. 1964) is a design historian and visiting professor with research interests in nineteenth and twentieth-century craft and design. She was curatorial advisor in the bauhaus imaginista project, tracing the flows of design ideas and expertise in India against the backdrop of decolonization, nationalism and Cold War diplomacy. Her current research is on ‘modern’ block printed textiles in western India and their adaptive response to contemporary issues and receptivity to global influences.