“An elephant on the eyelid is invisible, an ant across the ocean is visible”: Learning design from Akal-akalan practice archives

Unconditional design as a practice of archiving and transferring design knowledge

The desire to continuously explore and make new discoveries has existed since there have been humans, and it is safe to say that design has also existed as long as humans have. This, however, often goes unnoticed. As a result, some people argue that product design has only been around since modern times and is thus part of a modern or Western lifestyle.

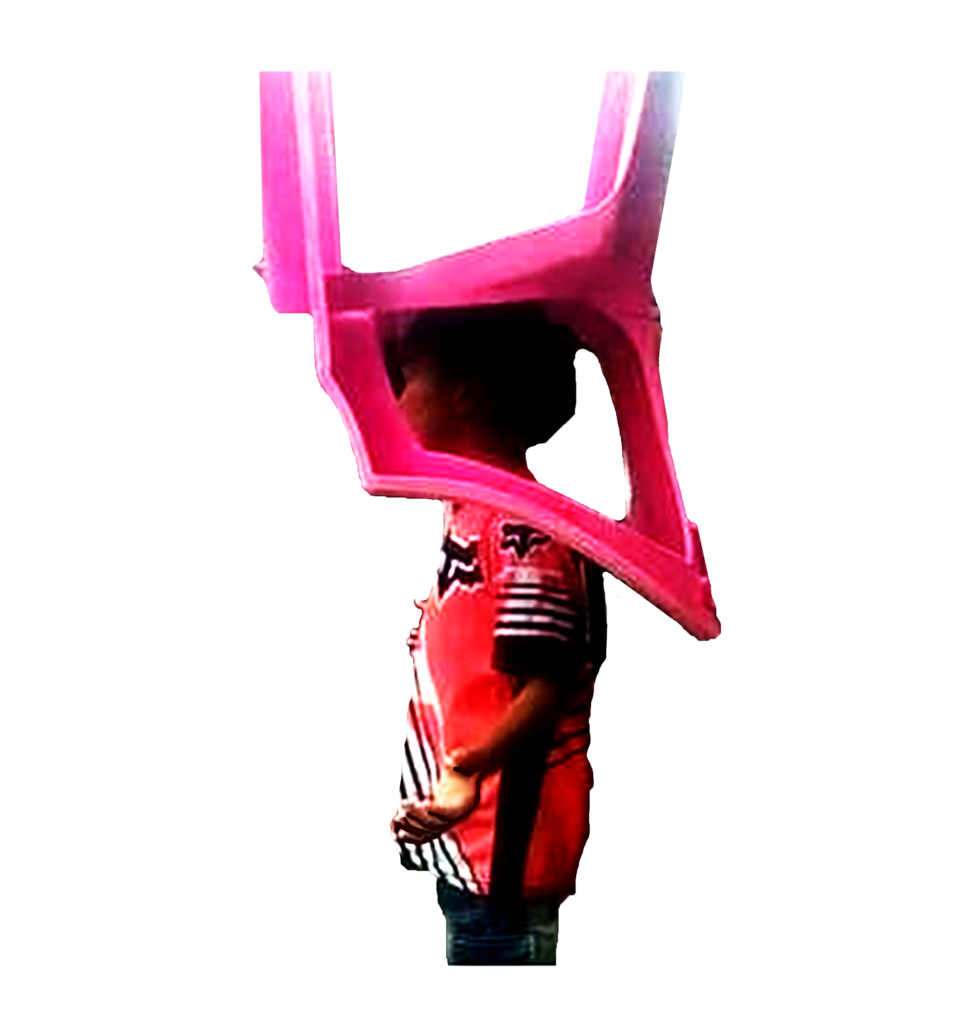

The term unconditional design, which can alternatively be translated as unconditional planning, describes the (renewed) design of a product, the main function of which has undergone change as a result of the creative process of the human mind with regard to the usefulness of that product. This topic is unpopular in the field of art and design academia because it is thought to lack a specific standard or reference point to discuss its methods and further regulate or study this practice. We do not know when humans began to change the primary function of a product after it outlived its original purpose or began to repurpose products by converting them as needed, influenced and encouraged by specific situations and conditions.

These adaptations are highly influenced by their originators’ creativity, experience, culture, needs, society, economy and environment. This causes the functional conversions to have different embodiments or design techniques from one region to another.

A new kind of creative process among citizens without prior design knowledge or design education, aiming to create designs with novel functions, has become a popular form of expression. In 2017, we finally decided to create an unconditional design platform on Instagram to collect the results. This platform is operated by the ruru ArtLab team and enables us to dissect the findings in a light-hearted way with product design discussions on each product shown. The project has expanded to several cities in Indonesia and has become a medium to channel contributions in the form of photos and videos using the hashtag #akalakalanwarga in each city or region.

As the unconditional design project expands, it becomes more visible in the form of knowledge exchanged through contributions on Instagram as well as stories about how a product is adapted before it is used. We also exchange knowledge in talks with people in the general community as well as academics. Unconditional design also opens up cross-disciplinary collaborations to discuss or make collaborative practices more challenging using unusual, neglected forms of programs such as workshops, seminars, joint exhibitions and interventions in public spaces.

Starting with a collaboration with Stuffo, we conducted the first unconditional design workshop, titled “Cooking Objects”, for participants at Gudang Sarinah, South Jakarta. The workshop was the first unconditional design inquiry to experiment with the knowledge of the participants, who were given a time and a location and were free to make anything using the available tools. All the workshop materials were unused objects, readily available around the site.

The second unconditional design trial was a collaboration with LabTanya, which created a short course titled Saturday Sunday Design Learning (SSDL). We conducted meetings every weekend with the participants at the LabTanya studio, providing a brief reading or design research assignment that was presented, discussed together, then investigated.

Our collaboration with LabTanya continues with a program we initiated in the city of South Tangerang. Fraktal City is an inter- and transdisciplinary experimental platform that involves and connects communities of residents with various challenges as well as problems in everyday life through the medium of design.

This program invited fifteen young designers, architects, artists or makers to collaborate with ten young people from five sites (villages and housing complexes) in South Tangerang for a month, forming an experimental laboratory and responding to topics linked under the title “Material Connects” at individual sites. As a provision of the experiment, the participants are supported throughout by facilitators and a series of classes, workshops, and discussions.

As a way to disseminate and celebrate the knowledge that was successfully produced throughout the program, the experimental results of the participants will be displayed in exhibition activities including a series of public programs and discussions and open lab activities (open experiments). Subsequently, each community site will be turned into a subject and design laboratory.

For a month, each team will map and reinterpret everyday life in their respective environments, finding things that can be used as tools to restore, rebuild or transform various possible forms of social and ecological relationships that exist in their communities. Experimental outputs are not limited to goods or products, but can also be systems, activity programs or something else.

Following the joint initiative, the unconditional design project was given the opportunity to participate in a residency, responding to and elaborating on ideas with the community of residents in the city of South Tangerang. Collaboration on a reading space in the selected village location and discussing and carrying out experiments together with the local community are among the proposed initiatives.

Making recordings of the memories of residents about spaces and objects in their daily lives over the past few years has also become a tool enabling interaction together in the village space. Through the observation, historical investigation and tracing of village narratives, the Jawara Waste Bank community, in collaboration with the unconditional design project, tried to reactivate and adapt some of the residents’ unique pastimes in the remaining spaces.

The social media used by the unconditional design project is one way for information collected independently to be transferred and redistributed, creating an open-source project on Instagram. This design research project is still ongoing today, finding an extension to the role of the people’s imagination in the city and in the interior of the village. The project saves the data in an archive of findings and categorizes them according to the type of product design, material, additional functional purposes, and space, which is the ideal approach to adopt.

Contributors who send photos of objects are also given the opportunity to discuss their findings, the results of which serve as descriptions for their posts. In this way, they discover new opportunities and points of views from reading about methods or inventive approaches and discussing them. Often, any knowledge about how a product of citizen-led repurposing becomes a functional form is not recorded or visually described because it is only exchanged orally between residents.

is a design research project founded in 2017 as part of the Ruangrupa Art Laboratory that aims to collect and study the phenomenon of informal design practices in urban innovation in Indonesia. UnconditionalDesign conducts participatory documentation and archiving through Instagram. This method has been successful in collecting hundreds of case samples from all over Indonesia over the past five years.