Concrete Steps—The METU campus in Ankara

The Middle East Technical University (METU) was founded in 1956 as a school of architecture and community planning under the name Middle East High Institute of Technology. It has grown into a full-fledged technical university and is one of Turkey’s premier research institutions.

Stepping through the main entrance for the first time is like passing through a magical portal. On the other side of that threshold is another geography with a forested environment and a cooler climate. You can see, smell and hear the difference from the city you just left behind. Once an isolated campus, now centrally located within the city’s boundaries and accessible by metro, the METU campus is practically a city in the city, albeit a different one than the one surrounding it.

Despite the contrast between the city and the campus, the scale of the ecological transformation accomplished and the immense political and economic resources it required leads some to compare and connect its story to Ankara’s history at the intersection of nation-building and urbanism.[1] The public imagination associates it with political dissent through the anti-imperialist student protests of the 1970s that were physically inscribed on its stadium as ‘devrim’ (revolution). Though critical thinking, organised activism and civic responsibility are part of METU culture—and one may hardly find cases that can match the scale of physical or ideological transformation seen in Ankara—the dynamics that allowed for METU to emerge and flourish are more likely to be understood from the constellation of people, events, policies and perceptions than from linear trajectories or singular, sensational events. The foundation of the school and its campus were concrete steps in positioning and integrating the country into the post-World War II world.

The contrast between this institution and other universities founded in the same period and ever since is as pronounced as the one between the city and the campus. METU is a product of the reorganisation of the world after World War II. Being one of the frontier nations to the USSR, Turkish educational and cultural policies were subject to the strategic programme to counter Soviet influence during the Cold War. On 5 September 1951, a legal agreement was signed between the United Nations and the government of the young Turkish Republic, which authorised Charles Abrams to conduct research on housing and city planning in Turkey.[2] Abrams, affiliated with the newly founded city planning department of the University of Pennsylvania (UPenn) and teaching at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), also worked as a consultant for the United Nations. The idea of founding an architecture and urban planning school in Ankara first emerged in a report that Abrams wrote for the United Nations Technical Assistance Administration.[3]

In the report, which concluded his yearlong research in Turkey, Abrams claimed that the solution to Turkey’s looming problems of urbanism and housing shortage lay not in international ‘experts’ coming in with universal solutions, but in ‘inperts’ who were to develop solutions fit for this context. Now familiar from various kinds of international collaborations, the mechanism was novel at the time. The school’s foundation was part of the shift from developmental policies to the formation of international nodes and networks. Despite the apparent dichotomy in its initial description between ‘experts’ and ‘inperts’, it created a new type of expert. In his book on METU and its place in post-war politics, Burak Erdim calls this new group of experts the ‘landed internationals’ and argues that the larger mechanism that produced them ‘brought legitimacy to both “experts” and “inperts” by positioning their new home, the academy, as the locus of a new political and industrial order in the Middle East.’[4]

The school officially opened in November 1956 as a school of architecture and community planning in rooms appropriated from service buildings of the parliament and the former house of the Turkish Pension Fund under the administration of UN-sponsored faculty.[5] At the time, it was known as the Middle East High Institute of Technology. Abrams engaged G. Holmes Perkins, dean of the School of Fine Arts at UPenn, who developed the curriculum for a school of architecture as the initial department of a new university.[6] In addition to creating the curriculum, providing the initial educators and later training Turkish academics, who were to continue the education through visiting positions at the university as the school grew, Perkins played another critical role through his direct access to Harold Stassen, Penn’s former president and the head of the Foreign Operations Administration (FOA).[7] Stassen, a seasoned academic administrator turned bureaucrat, had crafted the charter that opened the way for the legal and financial formation of the university.[8] Together with the founding president W. R. Woolrich, a former dean at Texas University, Stassen was able to devise an institution that followed the model of the state universities in the U.S. The charter secured public funds through the state treasury to an institution administered by an independent board of trustees. Such an institutional scheme, which is financially dependent but administratively independent, was a hard sell in the mid-century Turkish state. According to Uğur Ersoy, an emeritus faculty member who had joined the university in 1959, the year the decree passed, to have such a proposal approved by the parliament and treasury seemed an impossible task.[9] METU started out as an exception, and remained one in the following years.[10]

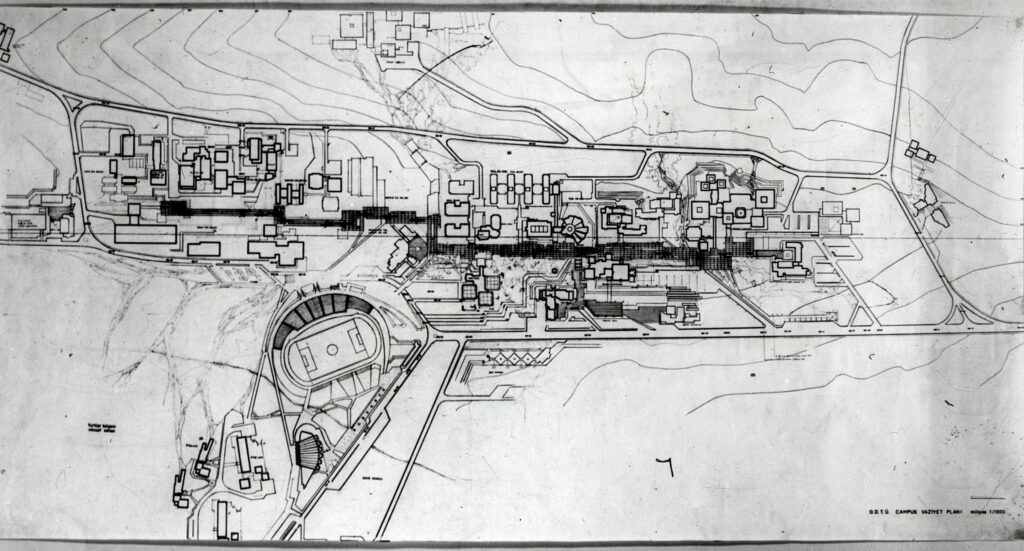

The idea of growing into a technical university and moving into a campus was inscribed in the initial institute. The UN-supported faculty had been working on competing schemes for the campus master plan for a few years when constructing one became economically feasible in 1959. Their proposal, devised for a hill on the city’s outskirts, composed the departments around a large courtyard, which was inspired by the Roman forum and the Jeffersonian campus plan for the University of Virginia. After a failed attempt to reproduce this scheme in partnership with a Turkish architect through a design competition—due to disciplinary authority conflicts—, the site was replaced with the current campus land. A new round of competitions followed. The campus we know today is the product of the design competition which Behruz and Altuğ Çinici, an architect couple, both graduates of Istanbul Technical University, won in 1960.

The competition brief remained the same; however, the site was significantly different. The winning team responded with an allée, an invention that united the requirements for a central open space that was supposed to cultivate interdisciplinary connections-which the forum initially provided-and the architects’ search for confirming and enhancing the topography of the longitudinal site with two ridges with an angle in between.

The new scheme positioned the academic centre, with its components along the allée, on the ridge that runs in the north-south direction. A second axis organises the non-academic centre, student and faculty housing, and recreational facilities. At the intersection of these two axes was the stadium, an ample open-air meeting space that brings together the whole university society on the occasion of the symbolic ceremonies of academic life.

Designing and building the campus were different tasks. Faced with the gargantuan tasks of building the campus and the forestation project it prescribed, the school of architecture and community planning had, once more, become the starting point. The METU faculty of architecture, the first college built, worked as an experimental site where innovative applications were realised to meet international standards. It effectively served as ‘the laboratory of new materials, mechanical equipment and construction techniques in Turkey’.[11] Waffle slab systems, exposed concrete applications, the production of fan coil units and the use of plexiglass in construction were among the several firsts in the country accomplished here. The financial and economic resources required to develop and standardise these techniques were afforded by the construction of the university. The concrete steps towards integrating the country into a global network of educational practices, finance and industrial production were taken here.

is an architect and educator. She is an assistant professor of architecture at Bilkent University, teaching design history, theory courses and design studios. She received her professional training in architecture at the İzmir İnstitute of Technology and holds an MArch degree from the Middle East Technical University in Ankara. She was a research fellow at the Bauhaus Lab 2018, a postgraduate programme on global modernities. In 2023, she earned her PhD from Virginia Tech. Her research and teaching are founded on theories of construction and the role of production tools and methods in design thinking. She has published her work as book chapters (Spector Books, Germany, Routledge, UK) and articles (Journal of Architectural Education, Footprint, Western Humanities Review) and has presented it extensively at national and international conferences.