Experimental practises of the Minimum Cost Housing Group

More than 50 years after its inception, Vikram Bhatt and Leonie Bunte assess the legacy of the Minimum Cost Housing Group, identifying five simple experimental approaches as key factors for the ongoing relevance of the group’s work.

In 1970, Colombian architect Alvaro Ortega, a UN housing expert, set up the Minimum Cost Housing Group (MCHG) at the internationally oriented School of Architecture at McGill University in Montreal to solve the challenging task of providing housing to the urban poor. For 50 years, under the direction of Ortega (1970–73), Witold Rybczynski (1973–88) and Vikram Bhatt (1988–2019), many researchers and graduate students from around the globe joined the team’s research effort to solve the problem. MCHG tinkered with innovative building concepts using simple technologies within the reach of ordinary users. Ernst Friedrich Schumacher theoretically approached small-scale technologies in his book Small is beautiful (1973) and had coined the term ‘appropriate’ or ‘intermediate technologies’ in 1962.[1] The Group approached it pragmatically, and rather than Schumacher’s philosophical dilemmas, their building experiments triggered practical questions such as: what could be accomplished locally, on a small scale and with simple tools; how to limit the use of scarce resources; ways of recycling industrial and consumer waste to turn it into minimal do-it-yourself-building solutions; and water conservation and low-cost sanitation. The MCHG’s ECOL Operation, an autonomous demonstration dwelling, and the line of ecological questioning are precursors to the contemporary quest for sustainability.[2]

In ‘Paper Heroes’ (1980), Witold Rybczynski questioned the concept of intermediate technology.[3] His critical review of the previous decade’s work ultimately provided a theoretical framework. Gradually, the Group moved beyond the university grounds to international locations collaborating with global partners to test and build. In a recent retrospective exhibition, Design for the global majority (October 2023), at McGill University, MCHG’s work was grouped into five practice fields: 1 upcycle, 2 harness, 3 plan, 4 leverage and 5 hack.[4] These serve as a good point of departure for the digital atlas of design education and technologies.

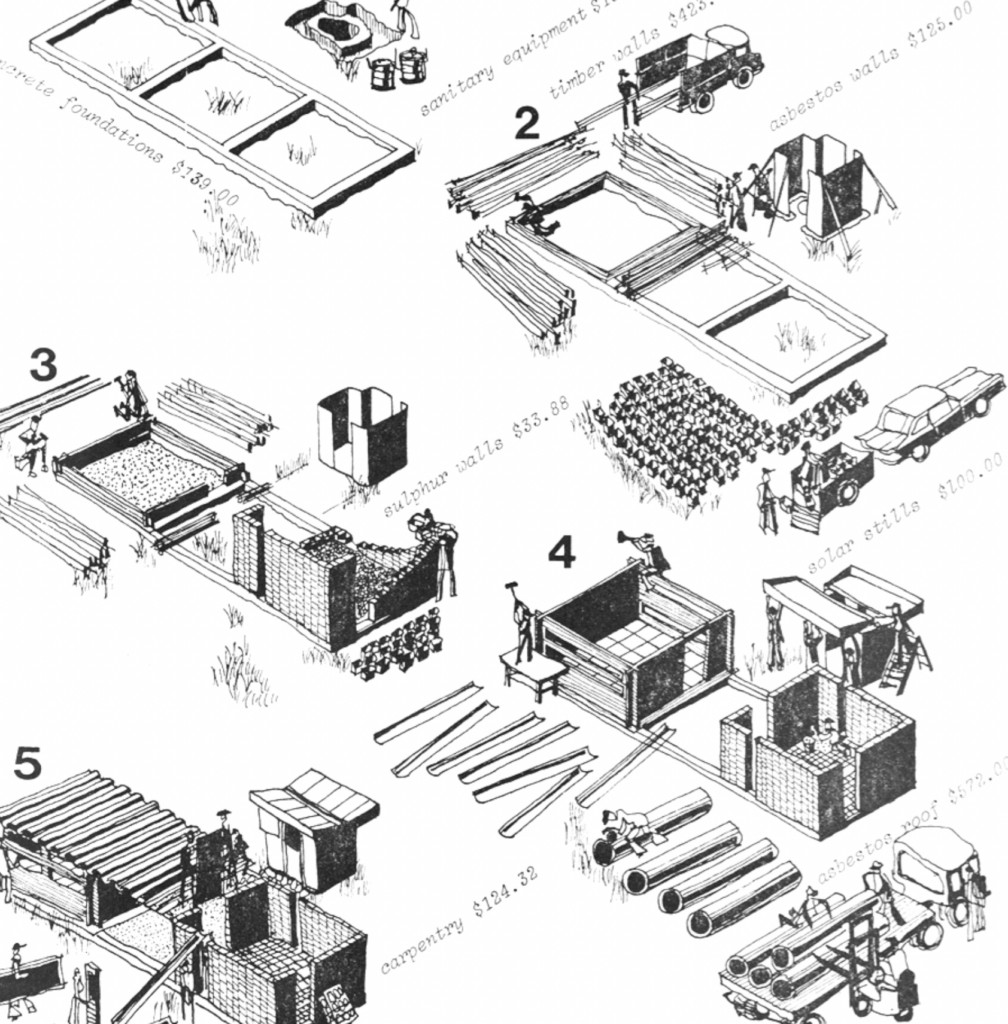

Recovering, recycling and reusing widely available, inexpensive materials like sulphur, MCHG used simple tools and technologies to transform them into small building components such as interlocking blocks for walls, floors and roofing. This experimental work was the first pragmatic step into the domain of ‘minimum cost’ technologies for the group. The tools used were adapted to limited resource settings to enable construction by a small group of individuals (figure A). The 1972 ECOL autonomous house for warm climates on McGill’s MacDonald Campus and the 1974 Maison Lessard, St-François-du-Lac, Quebec, designed for cold temperatures, demonstrated the innovative approach of the team and the potential of sulfur and other unconventional materials in buildings. Due to the rapid price increase of sulphur, related material research was discontinued; nevertheless, assembling small DIY modular components remained a distinctive characteristic of the MCHG’s work, and it was carried further into practice and even commercialised by colleagues.

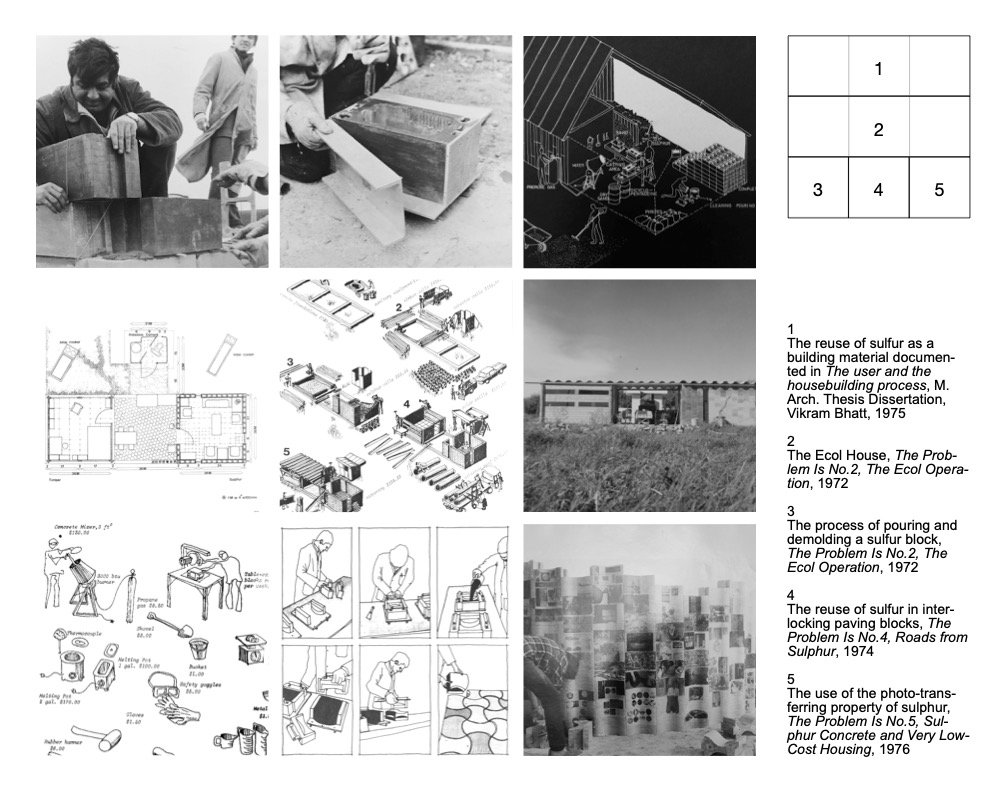

Potable water is a precious and scarce resource, so MCHG focused on conserving fresh water and dealt with low-cost infrastructure, particularly unconventional waterless sanitation experiments. In 1973, MCHG started exploring alternative waterless waste disposal systems and provided instructions for building composting toilets from the end-user perspective, confronting numerous challenges. This aspect of the MCHG’s novel work was quite varied and involved solar distillation to purify water, water harvesting or rain collection, recycling, garbage bag solar water heaters, atomisation to wash and conserve water, and mist showers (figure B). The outcome of this research produced two of the most successful MCHG publications entitled Stop the Five Gallon Flush and Water Conservation and the Mist Experience. The publications bridged international development research, the appropriate technology movement, countercultural lifestyle publishing and ecological design. This aspect of MCHG’s work was sometimes naturally overtaken and pursued by industry and local groups; today, the minimal water-using flush-toilets, showerheads, and faucets have become a standard utility. In India, Sulabh International, an NGO, successfully developed minimum water use composting toilets by understanding the interface between the user and the toilet and the common cultural practice of using water for cleansing. To date, Sulabh has converted millions of bucket latrines into low-flush toilets or pour-flush as they are popularly known.

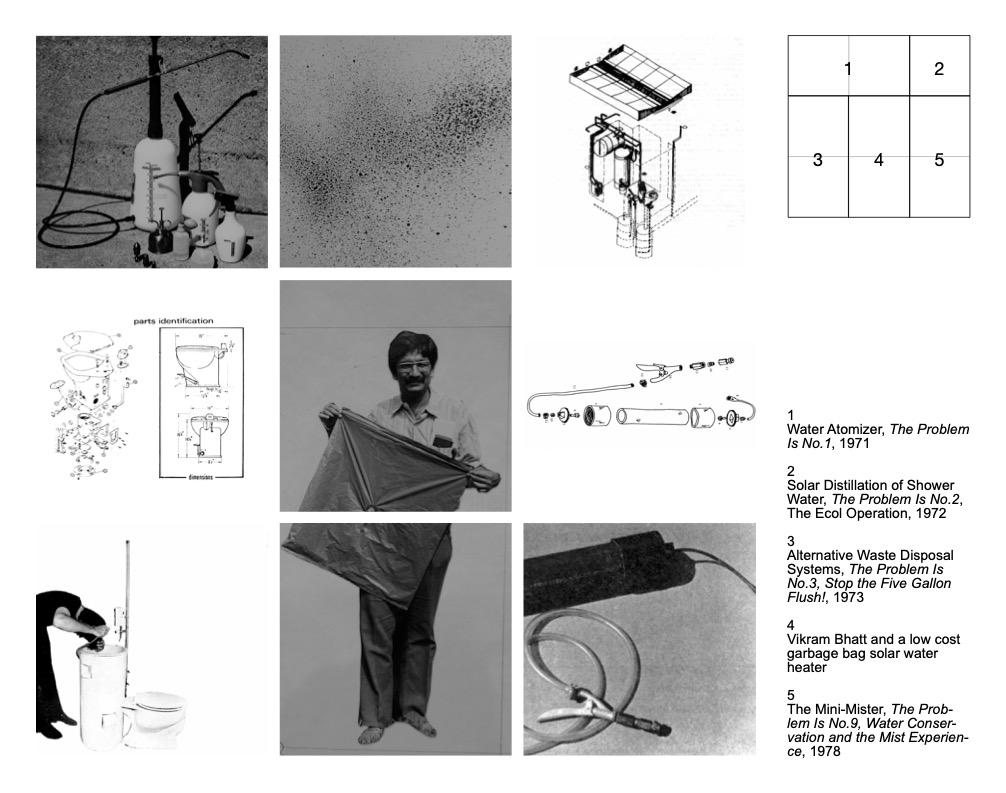

From the early 1980s onwards, the group started to document the architecture and spatial practices of informal settlements and their inhabitants, allowing MCHG to scale the work from small technologies to urban plans. The publication ‘How the other half builds, vol. 1′ (1984) captures the collaborative study with Balkrishna Doshi’s Vastu-Shilpa Foundation that was later applied in the award-winning Aranya low-cost housing project, for which the MCHG also designed a 200-house neighbourhood. Aranya became a teaching example in architectural education and for the municipal-level government staff working on the low-cost urban housing issues; it was further developed into self-contained audio-visual training packages. The MCHG team spent time in India, China and Mexico. It carried out intensive visual documentations of patterns and ways of living, crucial to deriving culturally appropriate norms from diverse lived experiences[5] (figure C).

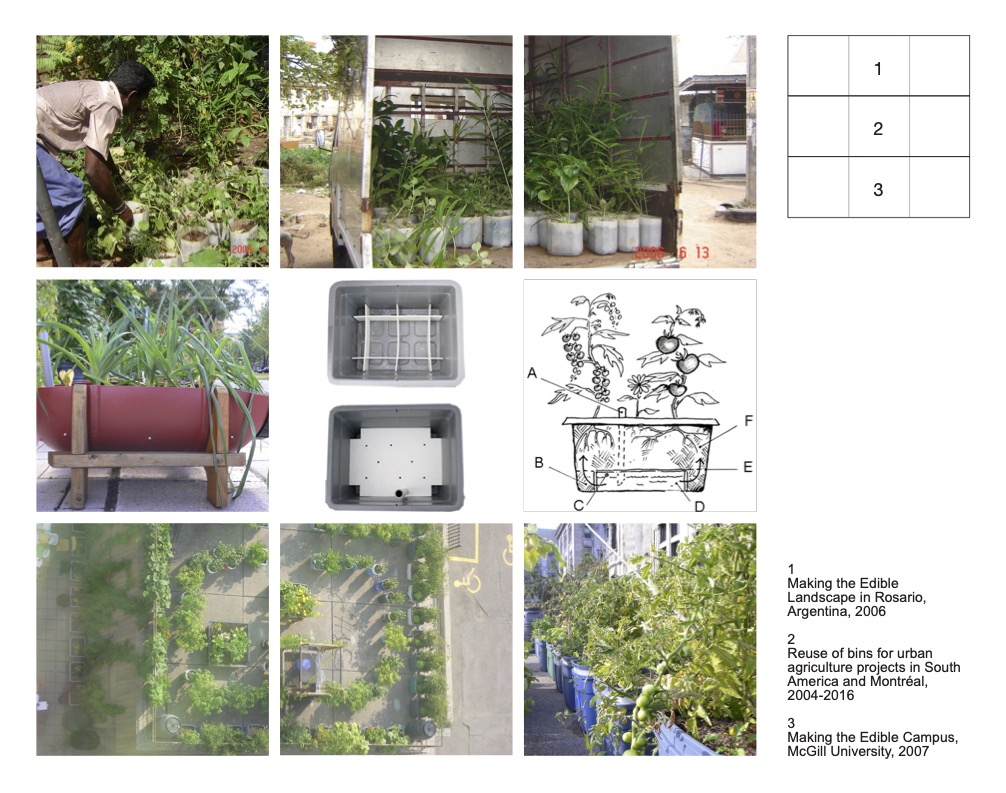

MCHG created varied edible landscapes by incorporating productive urban growing in different settings. The field has come to be known as urban agriculture, a misnomer because urban edible growing complements but cannot replace traditional agriculture. The rooftop gardens, a containerised edible campus garden of McGill University and different types of productive growing within poor neighbourhoods of Colombo, Sri Lanka, Kampala, Uganda, and Rosario, Argentina, are some projects that MCHG worked on (figure D). They show the range, flexibility and potential of this ecologically driven design thinking and are the reason behind the widespread acceptance and spread of this idea around the globe.

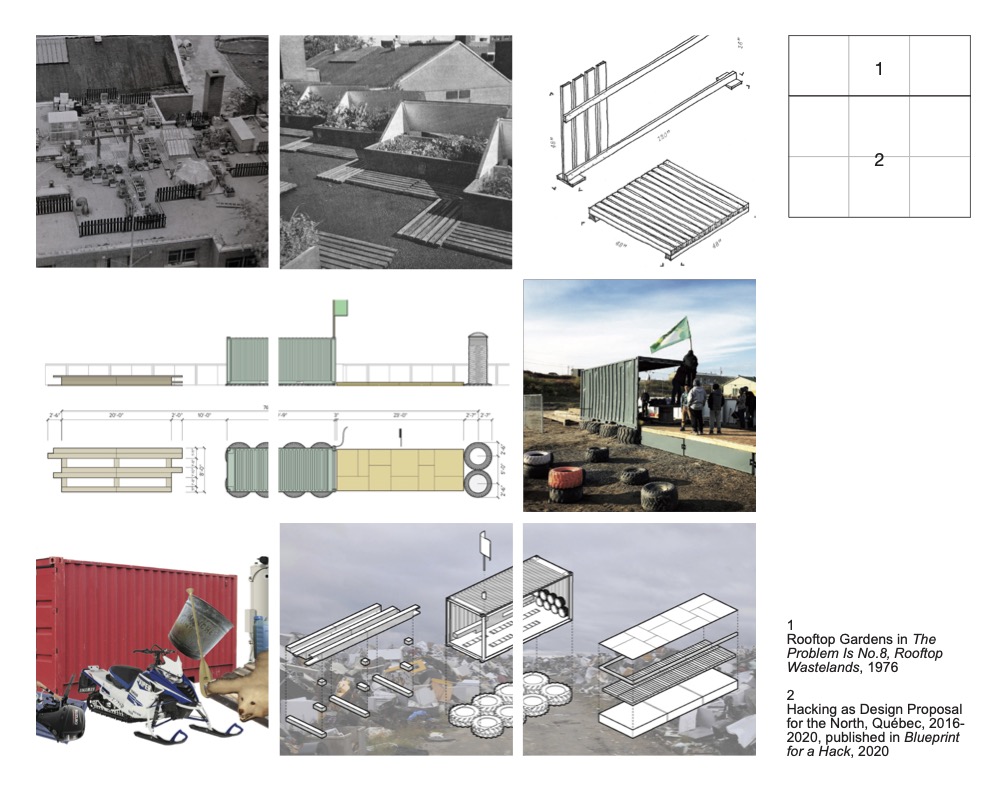

MCHG’s exploration into ‘hacking’, making do with whatever is at hand, began in the 1970s, focusing on transforming urban environments. This practice involved transforming empty rooftops in Montreal into urban gardens, documented in ‘Rooftop wastelands’ (1976). This early initiative showed the power of hacking to produce low-cost design solutions. The MCHG’s hacking application further emphasises the potential of recycling and reusing discarded materials and existing technologies. The group’s most recent project, Reconfiguring the North, carried out with the Northern Canadian community of Kuujjuaq, and described in the book Blueprint for a Hack (2020), illustrates the significance and widespread practice of DIY up-cycling culture and how to leverage it (figure E).[6] This hacking mindset enabled the MCHG to create sustainable, community-centred solutions with minimal resources throughout their work.

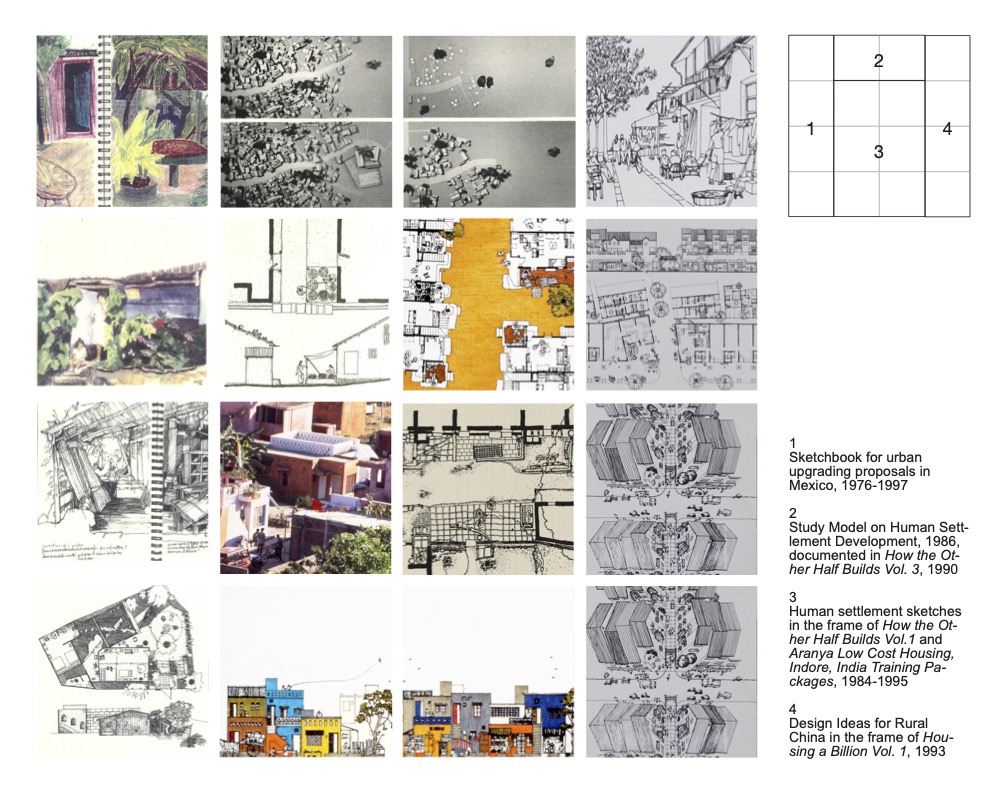

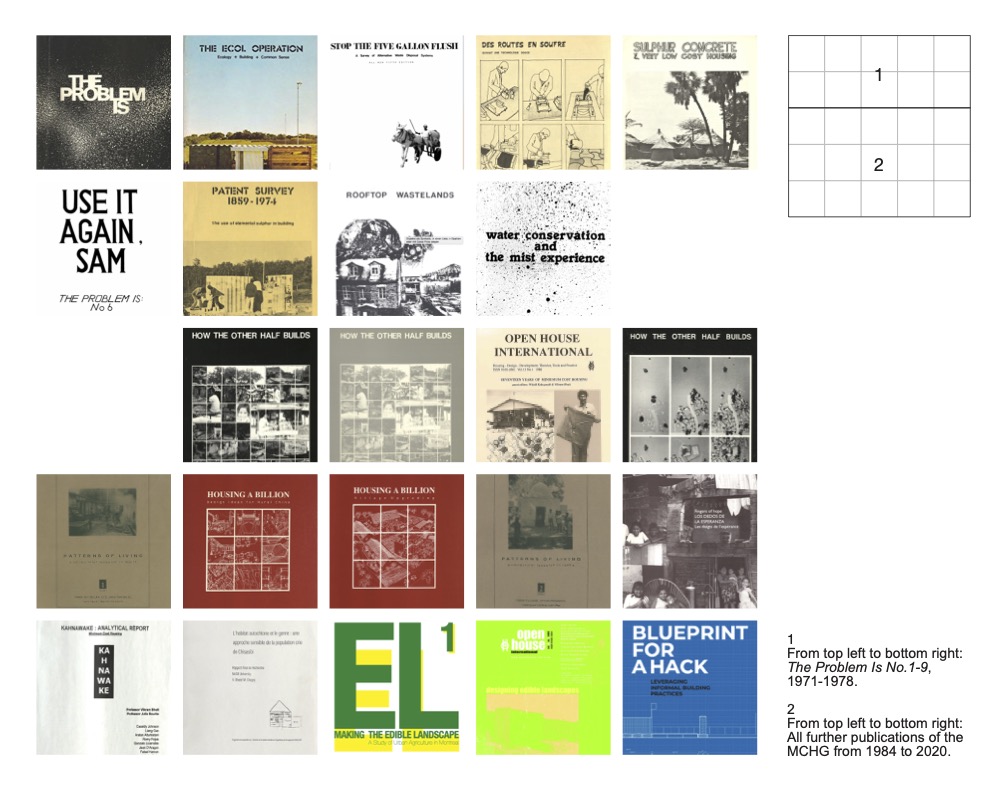

Documenting the various experiments, recording what worked and what did not, and sharing the results remained an integral part of the activity. Between 1971 and 2020, the MCHG produced over 20 publications, which were widely disseminated. An intermediate and visual mode of communication was crucial to facilitate the transfer of knowledge about various attempts, processes and principles. The publications, including documentations, instructions and toolkit lists, were ideal for spreading knowledge. The communication style of these publications was influenced by the vibrant countercultural media of the 1970s in North America, such as ‘The Whole Earth Catalog’ (1968), focusing on self-sufficiency, ecology, alternative energy and other topics related to holistic lifestyle practices. Hand-drawn illustrations were collaged with black-and-white photographs and short texts to make ideas and concepts clear and accessible. These books and pamphlets remain a source of knowledge coupled with MCHG’s budget concerns about low-cost printing and production techniques. Extensive hand-drawing and collage techniques proved to be effective communication methods throughout the publications, from ‘The ECOL operation’ (1972) to ‘How the other half builds’ (1984) and ‘Blueprint for a hack’ (2020) (figure F).

For 50 years, MCHG strived for minimum-cost solutions using simple technologies, using and refining them as necessary for specific situations. The iterative design process was easily cross-fertilised as the five experimental categories were not watertight; ideas and actions had considerable fluidity, which was advantageous because it provided a degree of overlap between them and gave coherence to the group’s work.

In the current context, some aspects of this line of questioning will have to evolve. For example, in urban greening, municipal bylaws in many cities require large roof surfaces to be covered by green roofs. Moreover, businesses, such as Lufa Farm in Montreal, have now taken over initiatives to create rooftop urban farms, so have supermarkets to grow produce on their premises. Commercial products are readily available for green roofs. Nevertheless, community action remains as essential as ever to advance and nurture edible landscape projects; we need good gardeners to have good gardens.

MCHG’s other strength was effectively disseminating ideas in print form (see figure F). The convergence of the printed and digital can help propel such ideas far and wide at a relatively low cost; however, these new platforms require special skills and training. One might consider whether the coherent intellectual approach behind MCHG’s work could be practical in the same way today, for instance, in addressing the present affordable housing challenge we are facing. With the users in mind, MCHG skilfully leveraged even small interventions like interlocking building blocks, garbage bags, solar water heaters and small container gardens; this mix of playfulness and hardnose experimentation, which set MCHG apart from other groups, remains valid.

● Vikram Bhatt is an emeritus professor at McGill University in Montreal. From 1988 to 2019, he led the Minimum Cost Housing Group (MCHG), focusing on housing affordability, settlement planning, urban design, minimum-cost housing and urban agriculture. He notably considered questions of where and how people can live interactively via the creative engagement of design. Most recently, he has been the co-author of ‘Blueprint for a hack: Leveraging Informal Building Practices’ (Barcelona/New York: ACTAR 2020). ● Leonie Bunte is a Ph.D. candidate in the department of architectural theory at RWTH Aachen University and a lecturer at the University of Idaho. In 2019, as a UROP scholar, she researched the Minimum Housing Group Archive at McGill University in Montreal.