Ken Isaacs’s Knowledge Box: An experiential model for learning

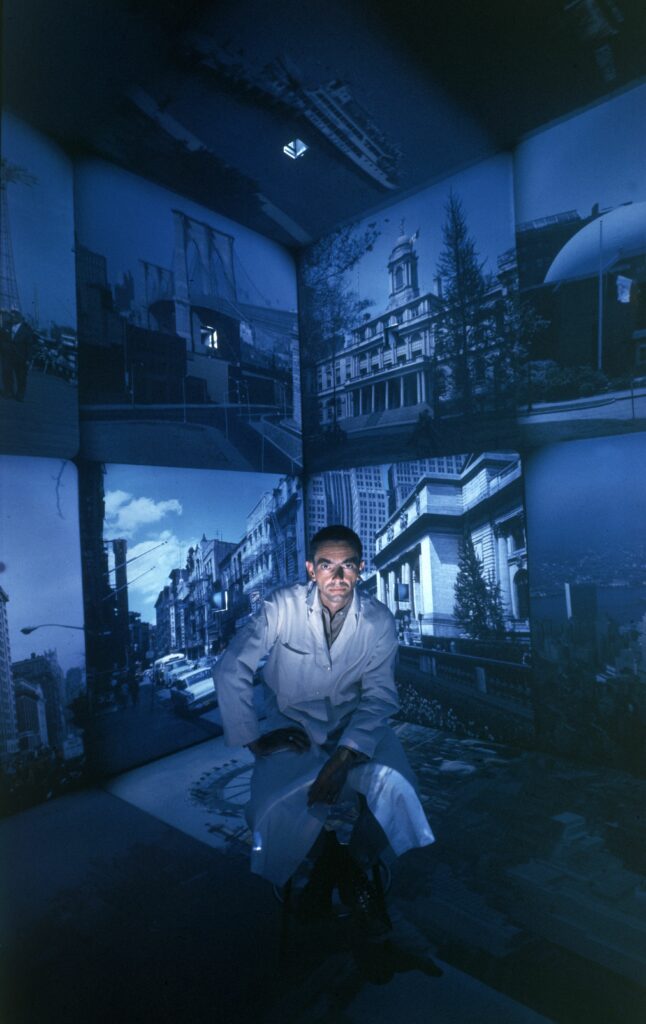

In 1962, American designer Ken Isaacs (1927–2016) appeared on the cover of Life magazine’s special issue devoted to the ‘Take-over generation’, young leaders forging innovative advances in government, science, business, the arts and education. Clad in a white lab coat and surrounded by projected images of coins, Isaacs is seen seated inside his Knowledge Box, a multimedia immersion chamber created with his students as part of a design course he taught at the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) in Chicago where he was a visiting lecturer from 1961 to 1962.

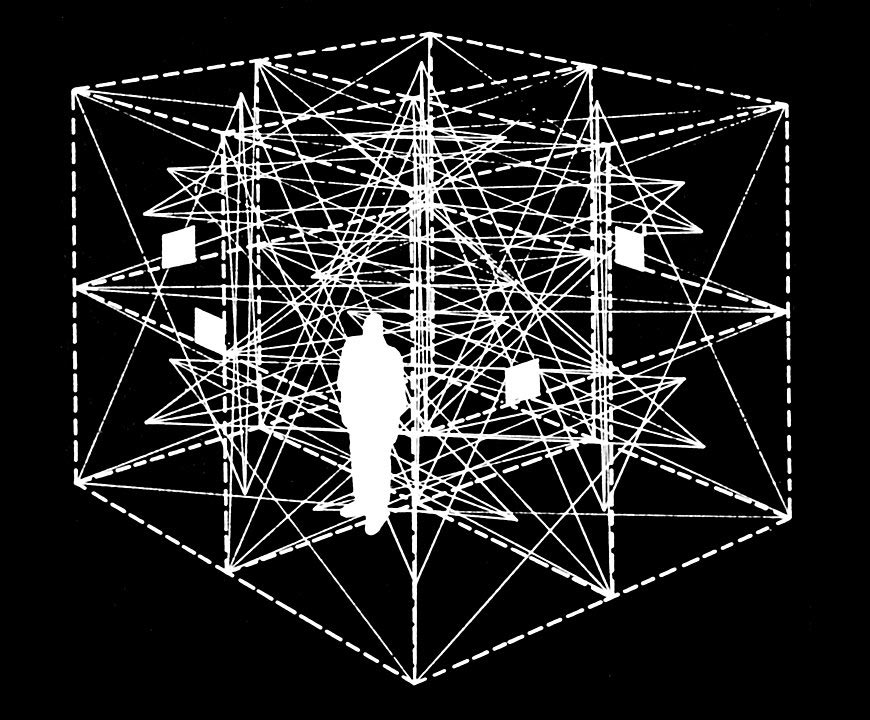

Initially installed at IIT within the glass walls of Mies van der Rohe’s Crown Hall, this twelve-foot-square wood and Masonite cube featured twenty-four slide projectors mounted along its exterior walls—including the floor and ceiling—so that each interior surface was cast with four images. Upon entering the Knowledge Box, a student was suddenly deluged by a rapid procession of images and sounds—transmitted through wireless receivers—that would build in a short, seemingly random sequence eventually enveloping the viewer. Shunning linear narrative, these slide images included photographs from Life magazine, maps, statistical diagrams and text excerpts as well as patterns of colour and light, all organised around a particular subject or theme such as the impact of population growth on the environment. Once the approximately five-minute programme ended, the student would exit the chamber and begin their educational journey by synthesising the image-ideas presented.

The Knowledge Box belongs to a series of information structures—what the designer also termed ‘alpha chambers’—developed over the course of Isaacs’s influential career that, in addition to challenging conventional architectural concepts in housing, sought alternative models to mainstream education. Eschewing the traditional classroom, Isaacs pursued an ‘environmental concept of education’, creating structures that were fabricated of information. ‘The elements of the alpha chamber were informational’, states Isaacs, ‘lacking the irrelevance of physical entities, and delivered so that the individual becomes the agent of synthesis. The old-fashioned student was a hitchhiker by virtue of being in touch only with sieved, edited opinions of the lecturer, author or film director. Why suffer the boredom, indirection and complexity of being perpetually at three or four removes from the data?’[1]

Alpha chambers translated course subjects into image-sound data sets, immersing the student in quick-flow information streams and modelling abstract ideas more concretely. This enabled each student to individually connect diverse ideas and historical events, ‘becom[ing] an active participant in subject-exploration rather than a passive receptacle of facts’.[2] The emphasis on comparative analysis has its basis, in part, in theories of cultural relativity as popularised by anthropologist Ruth Benedict, whose book Patterns of culture (1934) was profoundly influential to Isaacs. Applying the plurality and simultaneity of cultural experience to his alpha chambers not only afforded students a broader world view but also ‘an awareness of man’s relationship and responsibility to his environment’.[3]

These ideas were at the core of Isaacs’s teaching and design practice, both founded on his principle of the Matrix, or ‘total environment’, a formal and conceptual device based on a three-dimensional grid that was the central building component of his work. Isaacs developed his Matrix idea while at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, first as a graduate student (1952–1954), where he created his popular Living Structures—universal living equipment that integrated the disparate functions of individual pieces of furniture into a singular cubic frame—then later as the academy’s head of design (1956–1958).[4]

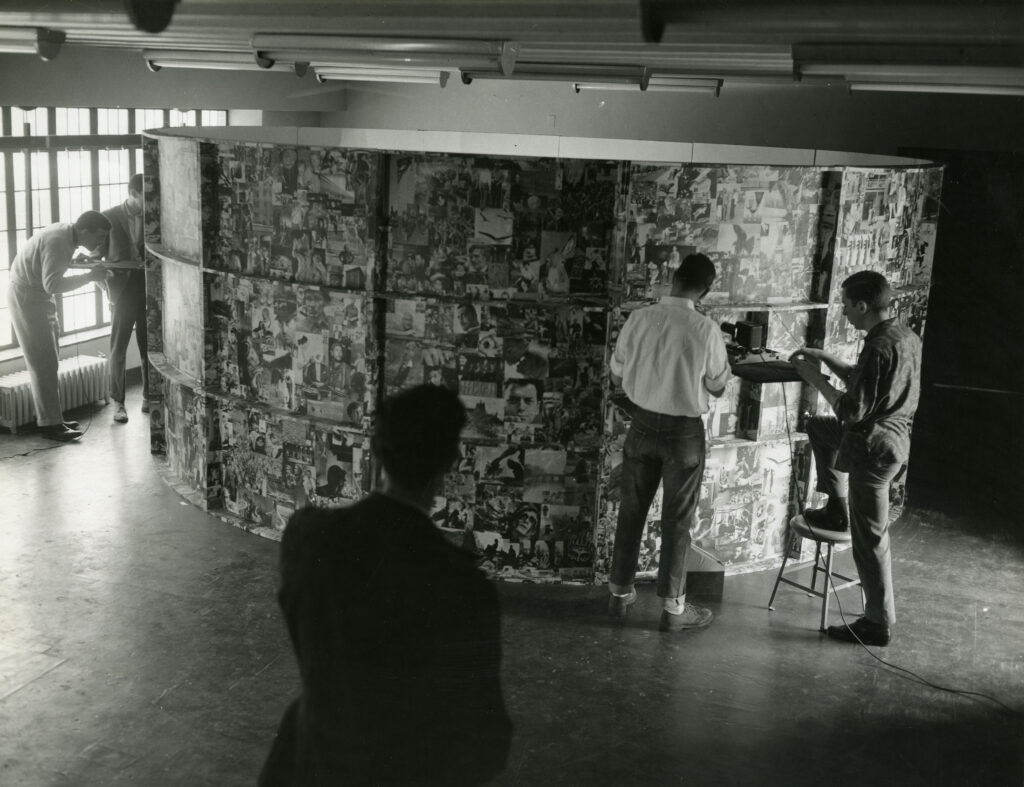

As head of design, Isaacs instituted the Matrix Study Course, which combined communications theory with the development of ‘processing environments’ aimed at teaching students how to use integrated systems to translate information and solve design problems, a curriculum that was used until 1980. This systems-based approach to design education is rooted in cybernetics as defined by Norbert Wiener, whose The human use of human beings. Cybernetics and society (1950/54) was required reading for his students as well as the subject for a series of class projects based on problem-solving techniques called ‘translations’. With the belief that experimental design education called for experimental educational tools, Isaacs developed the Matrix Drum, a circular wooden chamber, 18 feet in diameter, that was a precursor to the Knowledge Box. Inside, students were similarly barraged with an overlay of colour images cast onto the interior from three slide projectors positioned around the structure’s periphery, while an audio track filled the space with sound.[5] Covering the Matrix Drum’s exterior surface was a seamless photo collage or ‘pholage’, black-and-white images culled again from Life magazine, who Isaacs saw as a leader in the proliferation of photographs in print media during the postwar period. The purpose of pholage was to confront the viewer with visual information free from the ‘strictures of editing’ allowing students to create their own comparisons and meaning. According to Isaacs, ‘such a confrontation expands the consciousness. The viewer begins to see unique relationships between seemingly isolated incidents’.[6]

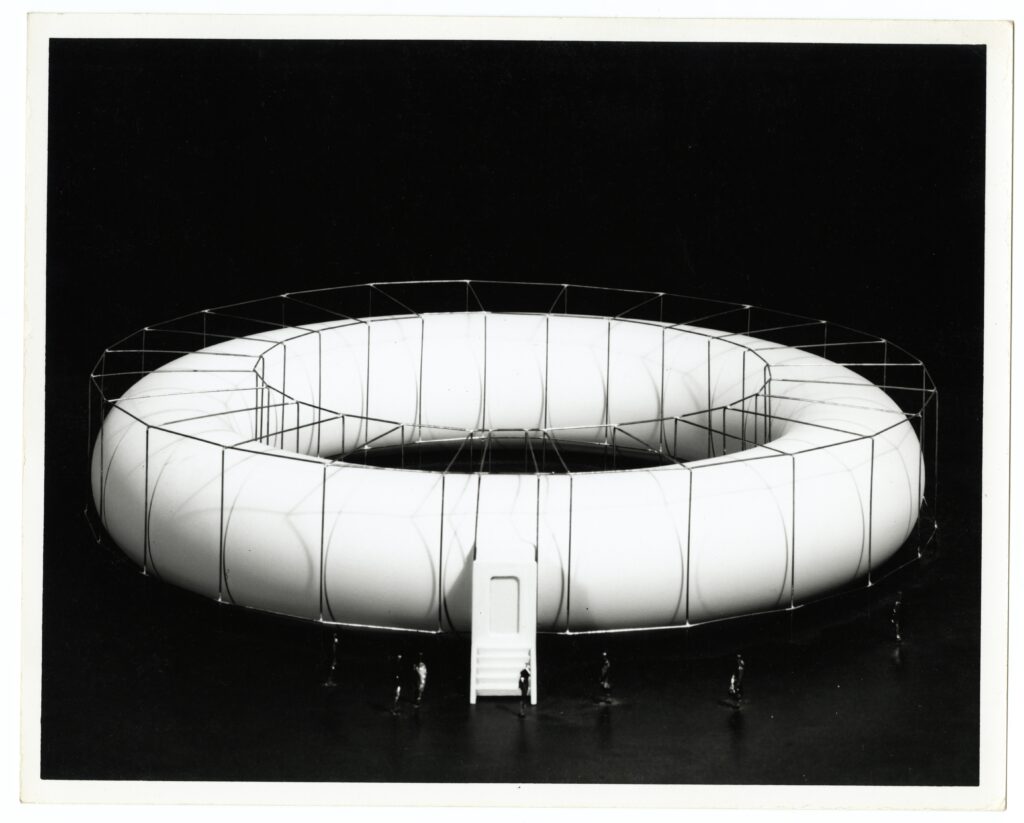

With a continued interest in Wiener’s ideas about the relationship between humans, systems and machines, Isaacs applied a networked model of information to his subsequent alpha chambers, including Torus 1, developed in 1961 with his students while teaching for a semester at the Rhode Island School of Design. Realised as a full-scale, cross-section mockup, Torus 1, like the Matrix Drum, was a circular wood chamber equipped with slide images and audio that offered greater ease of movement and ‘opportunities for cycling and choice in time phasing’.[7] That same year, Isaacs was invited to teach at IIT, where he created Torus 2; similar in configuration but made of a permeable plastic skin with a knock-down aluminium frame to mount projectors, it was conceived as a portable alpha chamber in model form.

Isaacs’s principal project at IIT was the Knowledge Box where students were involved in all aspects of the chamber’s fabrication, including slide content and production. One of the initial programmes, informally titled ‘People in ferment’, combined images of Brazilian peasants, piles of coins, mathematical equations and maps to explore the world distribution of wealth. Dubbed the Knowledge Box by journalist Clay Gowran in a 1962 Chicago Daily Tribune article, Isaacs’s new educational environment was widely covered within the mainstream press where some journalists compared it to sensory deprivation chambers and military brainwashing cells, the psychophysical effects of which Isaacs was aware of. ‘Our aim . . . was to create a totally new, totally strange, even seemingly hostile environment’, stated Isaacs. ‘Here all alone, a student is placed in an environment completely outside of his normal experience range and is exposed to rapidly presented information in an intense and exciting atmosphere. His immersion can be complete’.[8] Isaacs’s multimedia chamber also captured the cultural imagination, influencing experimental filmmaker Stan VanDerBeek’s Movie-Drome (1964–1965) and mainstream films like The Ipcress file (1965) by Sidney J. Furie, a British spy thriller that contained a brainwashing sequence based on the Knowledge Box.

Despite the Knowledge Box’s popularity, Isaacs turned his attention from the alpha chambers to pursue his Microhouses after receiving a fellowship from the Chicago-based Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts in 1963 to actualise the design and production of these small-scale, nomadic dwellings. However, Isaacs remained dedicated to exploring new concepts in learning, both as a writer and educator. Isaacs returned to academia in 1970, when the University of Illinois at Chicago invited him to teach at the school of architecture; he taught architectural design and served as the director of graduate studies until his retirement in 2000. From 1968 to 1972, he was a consulting editor to Popular Science, a science and technology magazine featuring DIY projects for general audiences, where he published easy-to-follow instructions on how to construct his Matrix designs, including a scaled-down version of the Knowledge Box, the Mediator, for use as a personal meditation hut. His now iconic book How to build your own living structures (1974) similarly offered tools for building and adapting his designs and living an ecologically conscious life to broad publics. Like Stewart Brand’s influential Whole Earth Catalog (1968–72 and occasional editions until 1998) and other ‘meta-manuals’ published by the countercultural movements of the period in which it was written, Isaacs’s guide for self-reliance and learning-by-doing was also ‘dedicated to challenging conventional methods of collecting and disseminating information in order to liberate their audiences from the strictures of conventional education’.[9]

Isaacs revisited the Knowledge Box in 2009 for the group exhibition Learning modern at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), which explored the impact and legacies of the New Bauhaus, now IIT. The original 1962 version no longer existed; thus, I directed the Knowledge Box’s complete recreation in close collaboration with Isaacs, realised at a slightly smaller scale to accommodate the dimensions of SAIC’s gallery. True to the original Knowledge Box, viewers are immersed in projected images, this time vintage black-and-white photographs selected from Life magazine’s archives. The entirely new 2:32-minute slide programme spans the decade of the 1950s—ranging from postwar agrarian scenes to images of advances in science and technology to portrait faces of popular artists, thinkers and political figures—collectively marking the rise of global modernity in keeping with the exhibition’s theme. A recreated audio track, received through wireless headphones fashioned from a DIY model that appeared in a 1957 Popular Science article, provides a brief aural montage of the decade.

The 2009 Knowledge Box was later exhibited in the travelling exhibition Hippie Modernism. The struggle for utopia (2015), organised by the Walker Art Center, which examined the intersections of art, architecture and design with the global countercultural movements of the 1960s and ‘70s. It was one of several multimedia environments representing the utopian experiments of a then new generation of artists and designers who—also informed by cybernetics—created networked communities and alternative models of information exchange. While similar in their employment of projected images, light and sound to induce altered states of consciousness, the Knowledge Box remains unique in its primary purpose as an educational tool.

The 2009 version of Isaacs’s alpha chamber exemplifies a particular historical period, yet one’s experience of it remains surprising contemporary given today’s 24/7 data stream. However, the original Knowledge Box captured and perhaps defined a certain cultural moment, while expressing Isaacs’s goal to model an experiential form of education. ‘If a wide enough spectrum of information can envelope the student, he will become disciplined by that knowledge rather than by any external force’, Isaacs once stated. ‘This has always been the aim and result of good education’.[10]

is a Chicago-based critic and editor, who writes about contemporary art and the built environment. She is author of Inside the matrix. The radical designs of Ken Isaacs (2019); her articles have appeared in Artforum, Art in America, and Textile. Cloth and Culture. She is co-editor of ARTMargins Online, covering art in East-Central Europe. She is a 2018 recipient of a Creative Capital/Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant for her blog, In/Site. Reflections on the Art of Place.