Editorial: Machines as teachers

In a letter to Walter Gropius dated 8 June 1938, László Moholy-Nagy takes a self-critical look at the past:

‘I am convinced that between 1920 and 1930, we, and most particularly I, overestimated the technical-scientific side of education and that the interpenetration of the three disciplines of art, science and technology must be more carefully examined.’[1]

Yet, fifteen years earlier, he had arrived at the Bauhaus as an artist and teacher, enthusiastic about technology and in high spirits, with a firm belief in art’s potential as an instrument of social change working hand in hand with technology for the good of humankind. In his teaching and his artistic practice alike, Moholy experimented with different media, moved fluidly between the fine and applied arts and pursued the goal of illuminating the interrelationship between life, art and technology.

Moholy wrote extensively about this practice during his time at the Bauhaus,[2] thus establishing his prominent position in the reception history of the school. His oeuvre came to epitomise an affinity for technology at the Bauhaus that purportedly spanned all areas. By 1925/26, with the school’s move from Weimar to Dessau, this took on a programmatic character. Machines, as the historiography of the Bauhaus would broadly state, were enthusiastically celebrated at the school as the harbingers of a socialist utopia rooted in universal equality and all-encompassing automation.[3]

This narrative, which was propagated by Moholy in particular, papers over the plurality of the approaches to education and design that were practiced at the Bauhaus.[4] Moreover, the shift towards the mechanised everyday world of the modern age which Moholy called for focused primarily on the application of new technological processes. Thus, despite the widespread use of mechanistic and technically orientated imagery and some innovations in form, the school remained stuck in a technologically deterministic position and therefore fell short of its own quasi-revolutionary aspirations.[5]

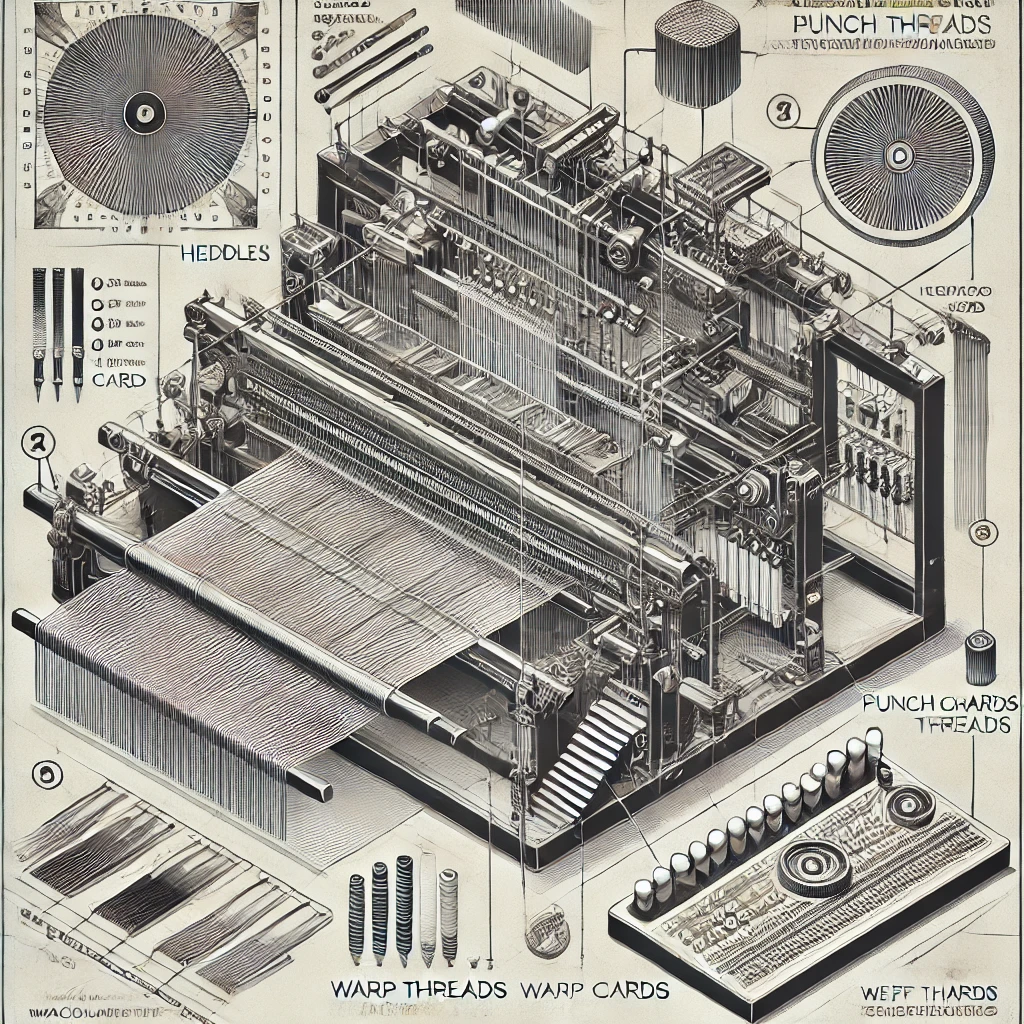

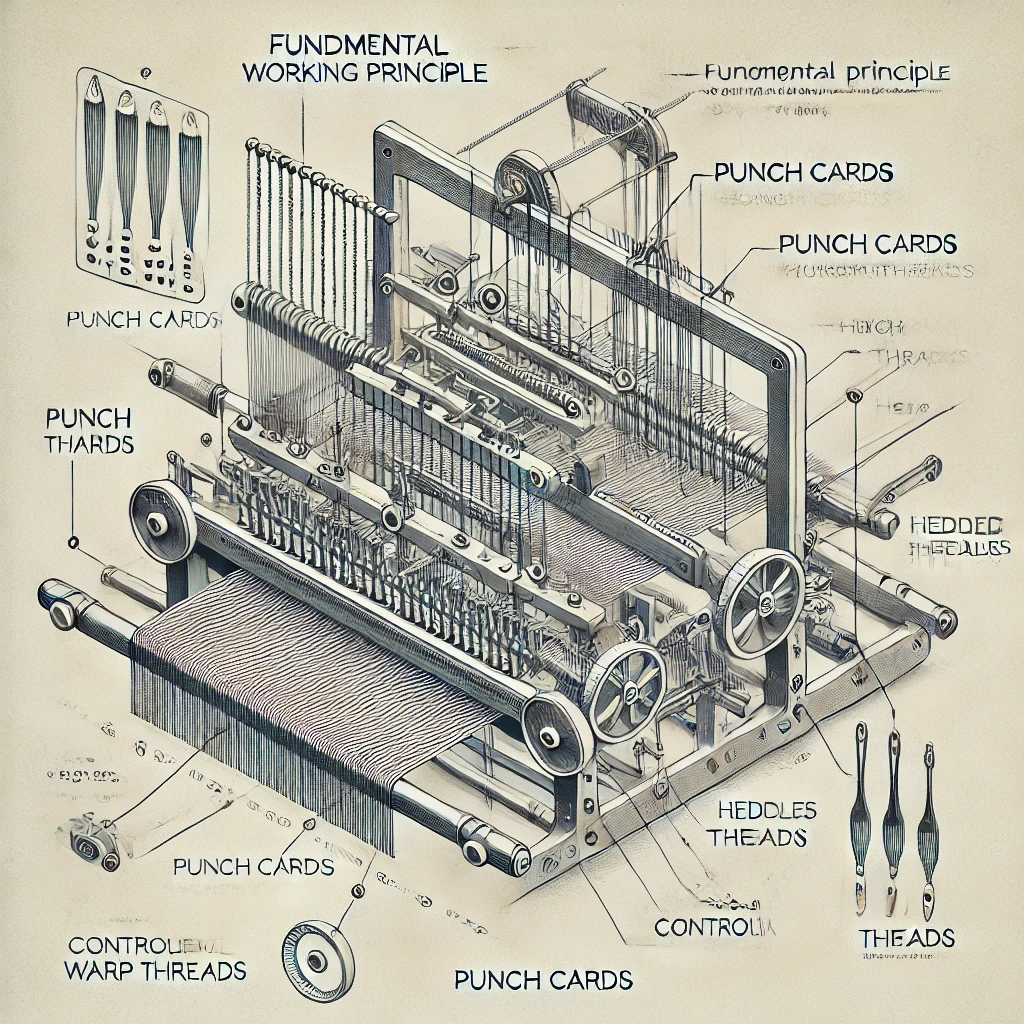

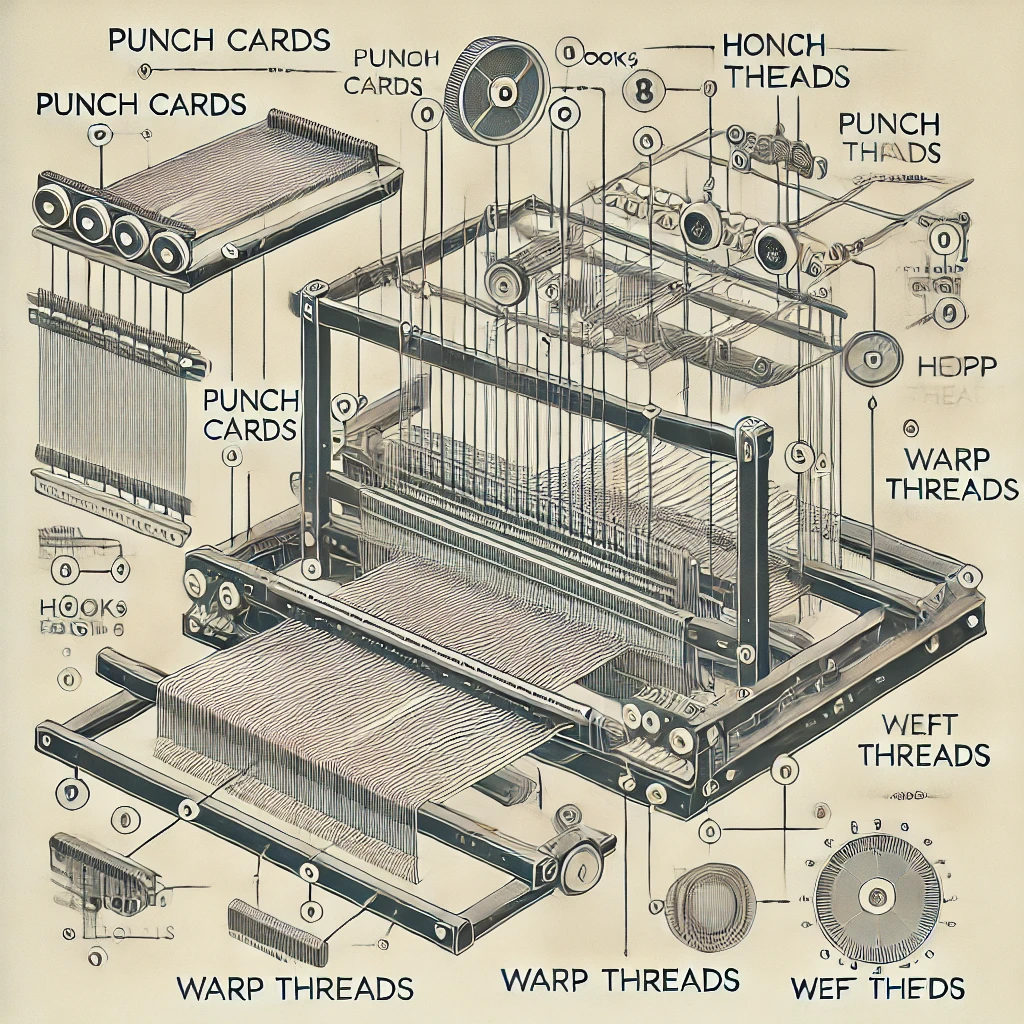

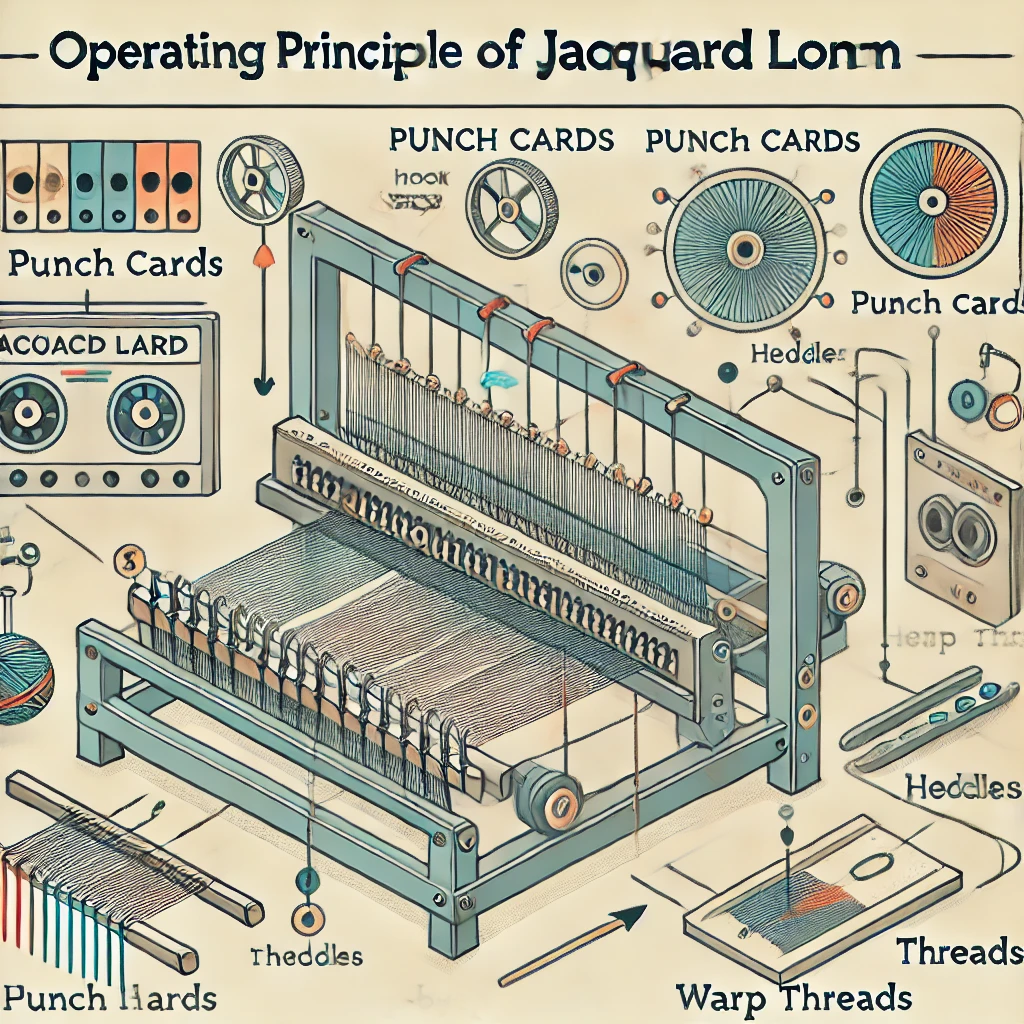

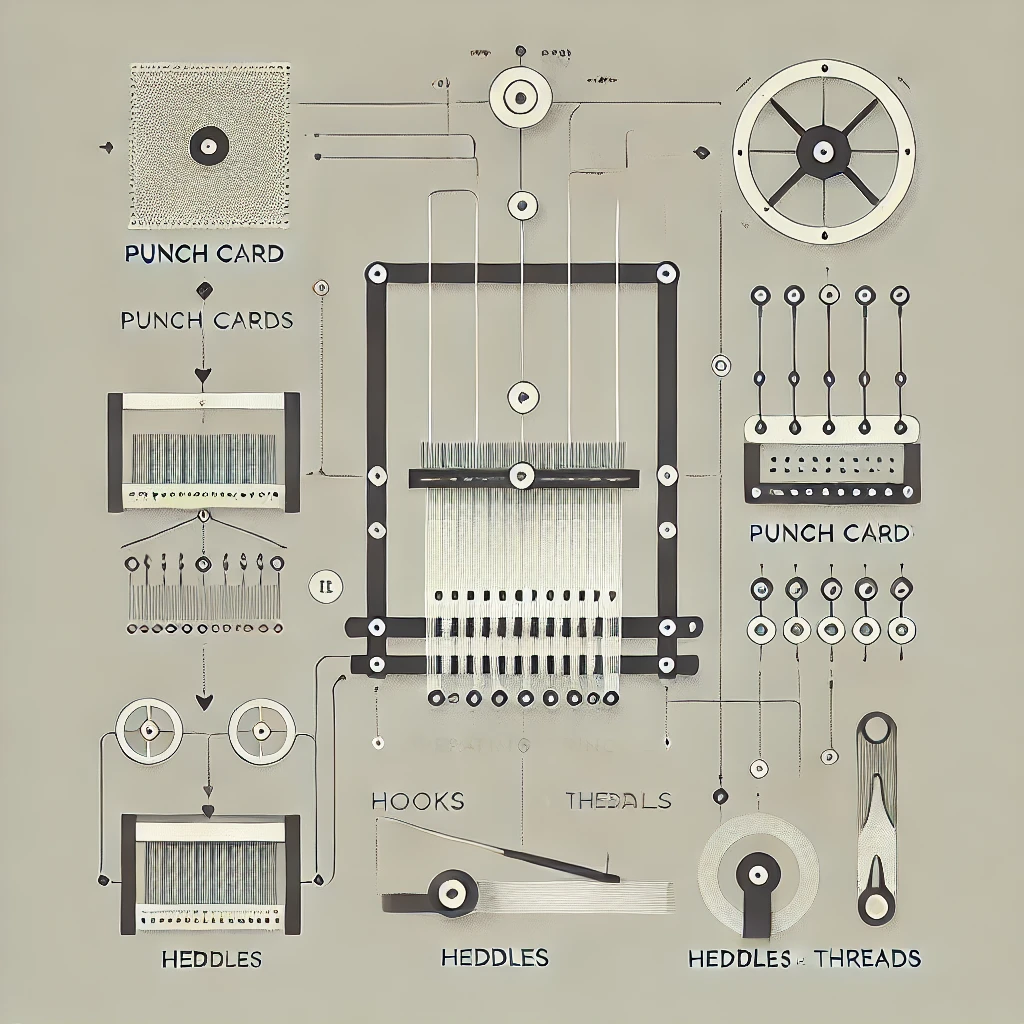

A form of algorithmic working practice in the interplay between humans and machines, which remains relevant from a contemporary perspective, was found of all places in a workshop that had long been excluded from a technology-orientated view of the historical Bauhaus, deemed a place of feminised arts and crafts: the weaving workshop with its Jacquard looms, which were programmed using punch cards.[6] The works created on these machines, such as Gunta Stölzl’s 1928 wall hanging Five Choirs and Lena Meyer-Bergner’s technical drawings showing the way the looms worked, attest to the technical expertise required to operate the machines in this workshop. Here, the close relationship between the production of everyday objects and the production of knowledge is plain to see: machine learning became an act of co-creation.[7]

In his book Vision in Motion, published posthumously in 1947, Moholy takes a somewhat resigned view of the interplay between technology, knowledge and progress:

‘The industrial revolution opened up a new dimension—the dimension of a new science and a new technology which could be used for the realization of all-embracing relationships. Contemporary man threw himself into the experience of these new relationships. But saturated with old ideologies, he approached a new dimension with obsolete practices and failed to translate this newly gained experience into emotional language and cultural reality. The result has been and still is misery and conflict, brutality and anguish, unemployment and war.’[8]

Nonetheless, Moholy does not leave his readers disillusioned by Vision in Motion. On the contrary, in this, his final book, he offers up analytical tools and new approaches to design and education, addressing the core questions: How can life be designed? Which potentials lie in design, in the role of the designer and especially in the education of future designers? At the same time, he is no longer impartially blinded by the great promise of technology.

The fourth issue of Schools of Departure focuses on the topic of technology in design education beyond the Bauhaus. In universities and research institutions during the second half of the 20th century, the belief in the triad of knowledge, technology and progress appears to re-emerge intact in a widespread move towards cybernetics. The relationship between design education and technology in the 20th and 21st centuries thus reflects the different ideas that designers and architects developed about machines – and the way they positioned themselves in relation to them.

The desire to practice, teach and study architecture and design as disciplines that derive their contents and methods from the so-called hard sciences is a recurrent feature of the efforts to reform education being made at the time. While this tendency is seen most clearly in the interconnectedness of post-war modernism, management theories, and the military-industrial complex, there is a strong technicist undercurrent in many projects that aim to renew design education, both before and after this period. But how is the inter-relation between design and technology actually handled in these processes?

In view of recent developments in the field of so-called artificial intelligence, this question appears in a new, lurid light. Generative processes of text and image creation such as ChatGPT, DALL-E and their competitors appear to bring within touching distance the all-embracing automation that still seemed utopian a century ago and that associated at least partial obsolescence of certain human tasks.

It is worth noting how the universal availability of these technologies turn the utopian projections of the modern age on their head, with the darkest dystopian predictions about the social function of AI applications coming from representatives of the technology industry itself of all people. As a result of the paradigm shift analysed here, from programming to training, it seems that machine learning is a project less concerned with information technology than with pedagogy. It is no longer first and foremost about unleashing the emancipatory potential of new technologies but about averting or at least mitigating the scenario of the subjugation of humankind by machines.[9] In view of these claims associated with the new paradigm of machine learning, it is helpful to contextualise the relationship between knowledge production and machines, based on selected historical and contemporary case studies.

Issue 4 of Schools of Departure gathers studies and ideas about how this dynamic has evolved in schools of design and architecture since the 1920s and casts light on the challenges that we face today. Over the last 150 years, hand in hand with the rapid growth of a technological network, our social environment has transformed into a world of data – a data-based society with new aesthetic, spatial, political and social cultural forms. We now live in a dense infosphere in which everything has a code, can be read by machines and monitored. This development will inevitably have an effect on the education and training of generations to come. For new designers in the field of architecture and design especially, this frequently prompts the question of whether they are learning the right basics and using the right tools, and to what extent do the courses or curricula have to change in light of this?

From 1920 to 1930, the Higher Art and Technical Studios in Moscow, known as VKhUTEMAS, pursued the aim of using the technological progress, scientific successes and artistic experiments of its day to override the supposed contradiction between science and creativity. Anna Bokov provides a glance into the school’s pedagogical practices by drawing on the example of the psychotechnic laboratory of architecture set up by Nikolay Ladovsky. Here, using custom-built measuring instruments and a systematic methodology that employed the conceptual devices of experimental psychology, theoretical physics and mathematics as ‘objective’ methods of design, the intention was to develop art and architecture as modern disciplines. Bokov believes the algorithmic calculations and proto-machine learning processes of this laboratory anticipate the advent of computer technologies and, at the same time, ‘propose a creative foundation for architecture as science’.

This spotlight on technological experiments that coexisted alongside the historic Bauhaus is maintained in a series of essays that focus on the instrumentalisation of innovations in media and construction technology to drive efforts to reform the education of architects and designers following World War II.

In his essay, Georg Vrachliotis describes the cybernetic visions of automated learning and teaching processes of the 1960s and 1970s that were developed in response to the Sputnik crisis as well as their continuing impacts today, based on educational discourses and building practices in the USA, Germany and Switzerland. Vrachliotis argues that the principlie of splitting up complex educational processes into modular learning quanta – an approach inspired by system theory – was also expressed in the designs for school and university buildings created by the Swiss architect Fritz Haller. Vrachliotis sees it as the task of today’s curators of knowledge to liberate the genuinely emancipatory potential of adaptive, technology-supported learning processes from its appropriation by military-industrial utilitarian logic.

John Blakinger sheds light on the limits of this emancipatory project in his essay on the work of the design theorist Gyorgy Kepes[10] at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Having developed the foundations while teaching at the New Bauhaus in Chicago, as a lecturer at MIT, Kepes wholly dedicated himself to the synthesis of diverse scientific disciplines in the new field of ‘visual design’. In a series of popular publications and exhibitions, Kepes attempted to shed light on the interaction of art and science in our interpretation of the everyday world, based on visual analogies between pictorial materials from the two disciplines. While Kepes successfully and permanently institutionalised this interdisciplinary approach in 1967 with the new Center for Advanced Visual Studies, the enthusiasm for technology propagated there was no longer well received within the university campus itself or outside it due to the involvement of the USA’s research institutions in the Vietnam War.

The campus as a site of technological and pedagogical experimention is the focus of Ezgi İşbilen‘s text on the history of the Middle East Technical University (METU) in Ankara. She defines the university of architecture and community planning founded by American government agencies in collaboration with Turkish stakeholders in 1956 as ‘the locus of a new political and industrial order in the Middle East’. İşbilen describes how, in order to meet international standards, innovative methods like waffle slab systems were used, fan coil units were produced, and plexiglass was installed. İşbilen presents the campus on the one hand as a building lab for new materials and construction technologies in Turkey and on the other as a hub of the Cold War network.

In Phillip Denny‘s essay, the interaction of the design paradigms, new technologies and geopolitical dynamics of the Cold War in the creation of new institutions, as illustrated by METU, is contrasted with the history of a research and teaching institution, the work of which highlights the difficulty of implementing approaches of systems theory in concrete cases, outside their original academic context. Denny focuses on the Building Institute at the University of Southern California founded by Konrad Wachsmann in the mid-1960s, examining its educational programme, the projects that were developed there and the politico-economic structures in which the institute was embedded. According to Denny, the somewhat meagre output of completed projects obscures the institute’s actual innovation, namely the formalisation of the work of teams in elaborate teaching systems. This was a lifelong project for Wachsmann whose legacy may be interpreted against this backdrop as primarily pedagogical in nature.

Following this, an interview with Gui Bonsiepe brings another region into focusm, ostensibly situated on the periphery of the East-West conflict: Latin America. Bonsiepe speaks about his career as an industrial designer and consultant moving between continents, addresses his work in the information department of the Ulm School of Design and provides insights into his further projects in Chile, Argentina and Brazil, with a specific emphasis on his interface design for the Cybersyn project that was implemented during Salvador Allende’s period in government (1970–73).

Another device to synthesise information from data and knowledge from information is designer Ken Isaacs’s so-called Knowledge Box, the subject of the following contribution by Susan Snodgrass. Isaacs designed the model with students at the Illinois Institute of Technology (ITT) in Chicago in 1961/62. The Knowledge Box was one of a series of information spheres that Isaacs developed as educational tools and alternative models to those of a conventional design education. His systems-based and ecologically-orientated approach to design education referred to Norbert Wiener’s work on cybernetics. Together with Susan Snodgrass, in 2009 Isaacs reconstructed the Knowledge Box for the group exhibition Learning modern at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC).

The connection between technology and the military that informed earlier articles takes a back seat in the following contributions; the historic and contemporary case studies addressed here are based on a fundamentally democratic understanding of technology. Thus, in their essay Vikram Bhatt and Leonie Bunte use selected projects to present an overview of the work of the Minimum Cost Housing Group (MCHG) founded in 1970 at McGill University in Montreal by the Columbian architect Alvaro Ortega. The authors introduce five practices of minimum cost housing and examine them in relation to the concept of ‘appropriate technologies’ coined by E. F. Schumacher. Bhatt and Bunte emphasise that the use of simple technologies was crucial for the success of the group’s projects.

Maria Göransdotter paints a picture of the project UTOPIA (1981–85). In the context of Nordic newspaper production, UTOPIA established an exchange between researchers from Sweden and Denmark collaborating with union members and skilled workers from the printing industry, the aim being to develop a series of computer-based tools for text and image processing. Here, screen-based work was simulated on simple prototypes and cardboard mock-ups. Based on the concept of a technical laboratory for test models, design was practised in a collaborative, application-orientated, interdisciplinary and democratic manner. In addition, inspired by the writing of Paulo Freire, the project also examined power structures in the workplace and gave workers power over the design of technologies. In her contribution Göransdotter emphasises however that the design practices developed by UTOPIA were not intended to criticise the phenomena of exploitation and alienation, but rather to bolster the optimistic view of workplace democracy, social justice and participation.

Finally, an interview with Aldje van Meer outlines how technological developments can be pragmatically realised and anticipated in teaching at a school of art and design. In the framework of comprehensive institutional reform at the Willem de Kooning Academie in Rotterdam, the school turned away from workshops as an organising principle of knowledge production and instead introduced interdisciplinary ‘stations’. As one of the co-initiators of this project, van Meer discussed the history of the project’s origins and speculates about its possible future.

●

Picture right: Katharina Jebsen, Jacquard gobelin (contemporary interpretation of a design by Gunta Stölzl, 1928), detail, 2022. Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau (I 46952/2) / © (Stadler-Stölzl, Adelgunde (Gunta)) VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024 / © Jebsen, Katharina / Photograph: Gunter Binsack

are research associates at the Academy of the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation and have been leading the digital research project ‘Schools of Departure’ since 2021.