Stations, not silos: Interrogating the workshop paradigm at Willem de Kooning Academy

A major institutional reform at the Willem de Kooning Academy (WdKA) in Rotterdam saw the school shift away from workshops as the organising principle of knowledge production, introducing interdisciplinary stations in their place. In an interview with Katja Klaus and Philipp Sack, WdKA senior lecturer Aldje van Meer reflects on the project and speculates about its possible futures.

You were instrumental in implementing a wide-ranging reform of the workshop model at the WdKA in 2012 when the school replaced the formerly artefact- and material-oriented workshops with a flexible set of ‘stations’. Can you elaborate on the intentions behind this shift and reflect on its merits twelve years on?

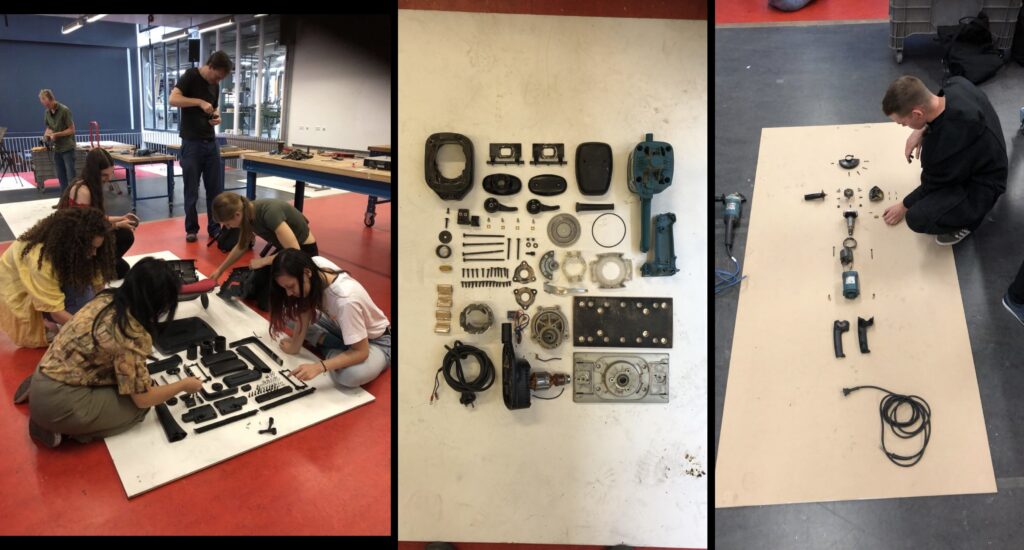

The shift had pragmatic reasons: new deans felt the academy was no longer representing contemporary art and design practices. They introduced educational changes, and we worked on a curriculum change with a large team of tutors in a democratic process. The stations arose from these curricula change meetings. We saw that art and design practice was changing, with interdisciplinary approaches now becoming the new standard. We believed that a changing society also calls for new ways of making. New technologies, societal and economic developments not only alter the way we make things, but they also influence how we think about cultural production, work and its practice.[1] We did not see these new ways of making reflected in the workshops: they were very artisan-oriented—printing, wood and metalwork facilities. We identified a deficit in digital technologies which were already influencing artistic practice to a large degree.

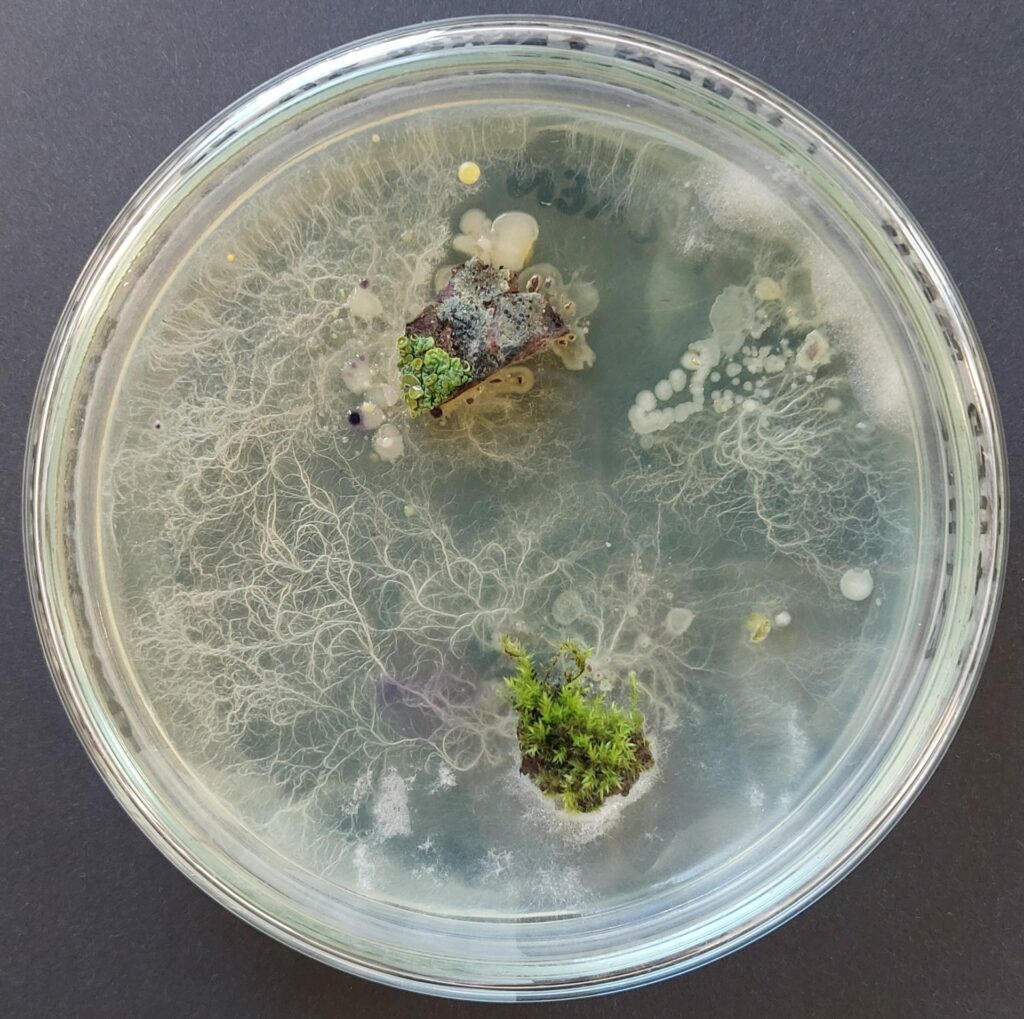

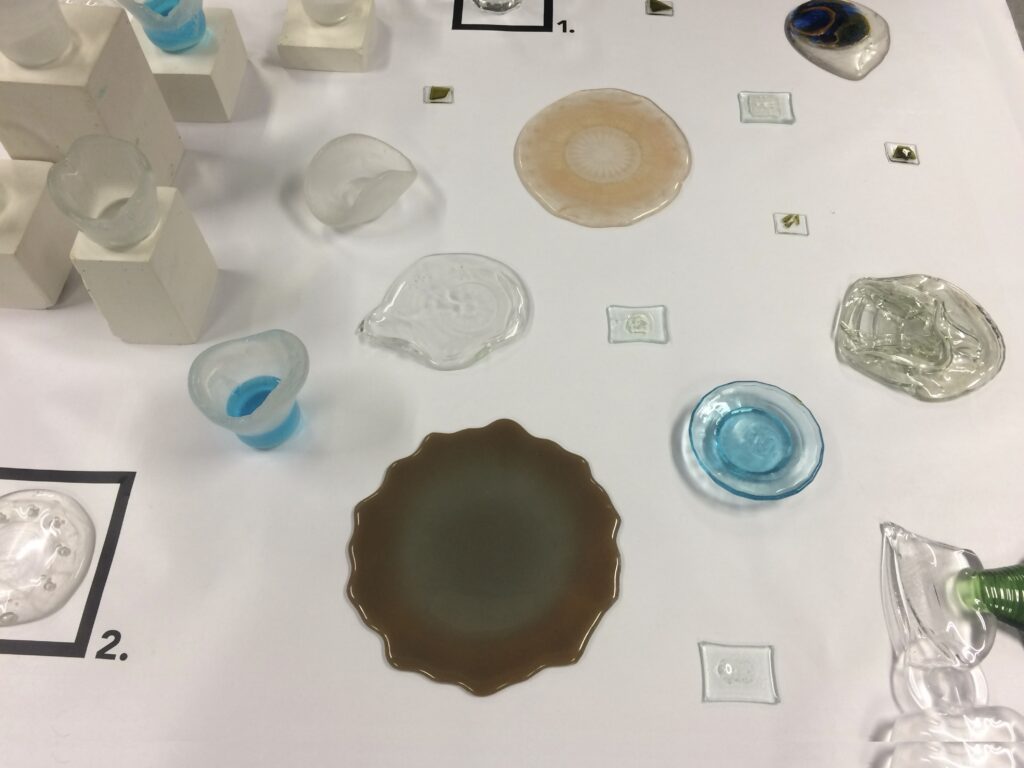

This led to the creation of the WdKA Stations, a successful rethinking of the workshops in which I was able to bridge the gap between contemporary art and design practices and the 20th-century craft-oriented education. By making such a connection, this transformation allowed the workshop to become more than a site of production and execution; it also became a space where research through making can take place. In the stations we were able to embed new technologies so students could experiment while continuing to work in their respective departments. We also wanted to respond to changing practices in art and design, where outcomes were not just artefacts anymore but processes and experiences too. We aimed to integrate technology and material knowledge into the creative process, refuting the prejudice that technology was limiting students’ imagination.

In a previous conversation, you mentioned that you think of the stations as being interdisciplinary, not transdisciplinary. Could you please elaborate on that distinction?

The stations are an intervention in interdisciplinary education, particularly alongside another significant curriculum change we implemented in 2012. Since this curriculum change, students work on real life—practical assignments which transcend the boundaries of their discipline. Within these educational programmes, much effort is put into rethinking systems, notions of authorship, collaboration and interdisciplinarity. This change was crucial because we wanted to respond more effectively to societal developments and needs, fostering projects that involve collaboration with various stakeholders and community members. Initially, our workshops were closely tied to different majors. For example, visual design students primarily used workshops related to audio-visual media. However, a significant change came with the introduction of the stations. We disconnected these workshops from specific majors (disciplinary studies), creating an interdisciplinary practice environment. Now, stations like for example the fabric station are utilised not only by fashion students but also by students from fine arts, product design and various other disciplines. From the beginning of their programme, students in these practice programmes work together across different disciplines, integrating their learning experiences. This interdisciplinary approach is a core aspect of our stations and represents a major shift in our educational practices.

The maintenance of the stations requires you to constantly adapt them to the most recent technological developments. What kind of modifications did you implement since 2012, and in reaction to what? From our own experience, the occasionally ossified institutional structures we’re working in as educators sometimes appear hard to square with the fluid dynamics of technological innovations. How do you negotiate the different temporalities at play here?

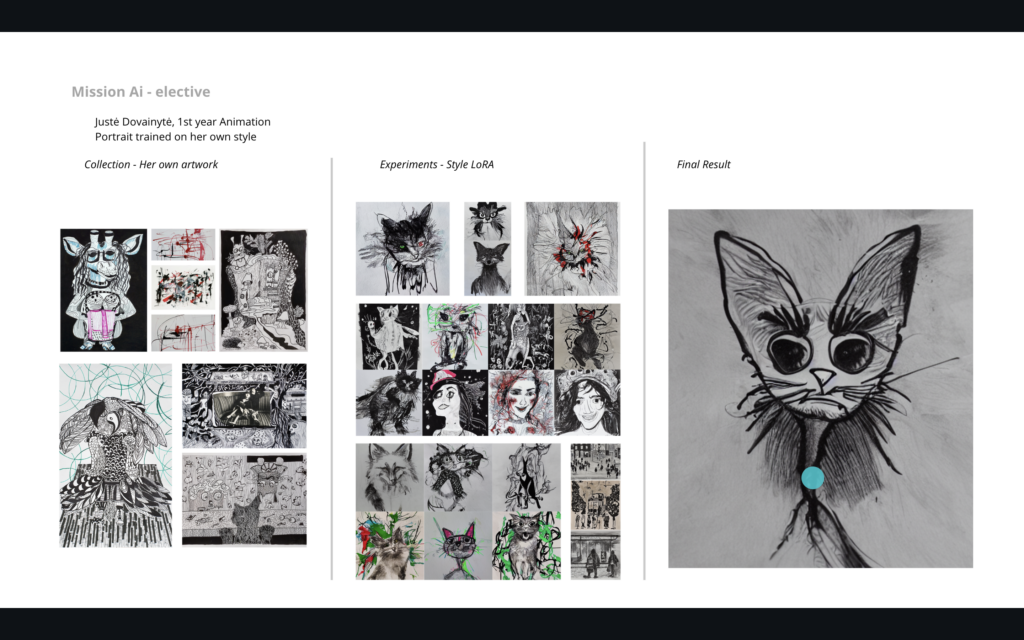

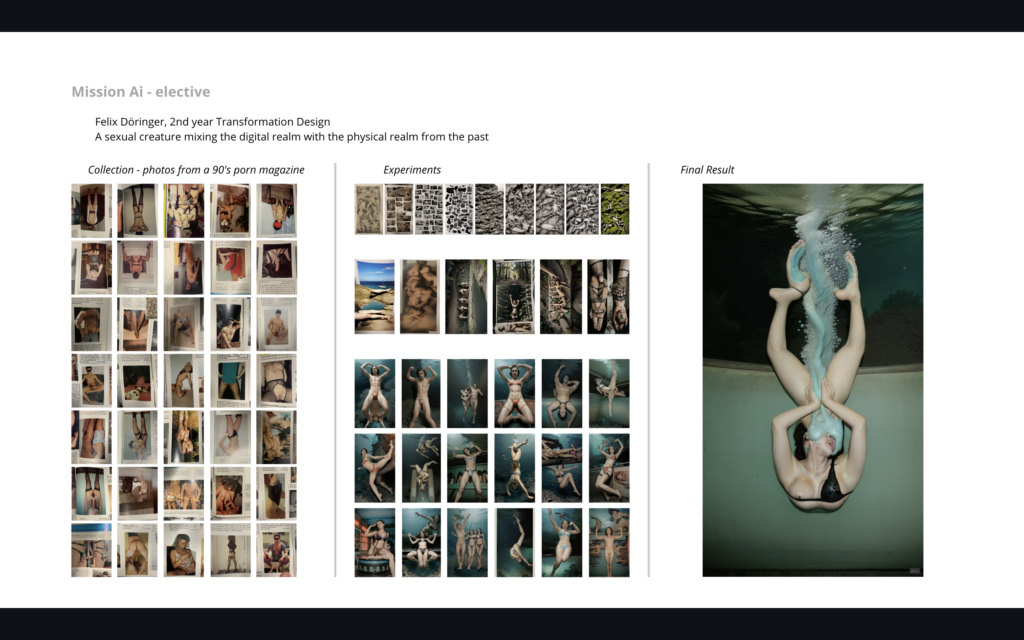

To give a concrete example: the publication station initially focused on print techniques like silkscreen, lithographs and letterpress. In the years after 2012, we introduced digital crafts, like the ability to use laser cutters, vinyl cutters and digital printing alongside the traditional technologies. We also have a new studio dedicated to digital publishing and e-publishing. This extends beyond digital publishing to include editorial design and digital typography. It’s interesting to reflect on this because we’ve changed so much in the past ten years. It all sounds logical now, but just a decade ago, we were behind in these areas, as were many art schools. We’ve now firmly established these digital technologies. Another example is the interaction station, which has been operating since 2014. Initially, nobody knew what the Interaction Station was about. Today almost every student and teacher collaborates with it. The team consist of nine instructors/teachers, each with their own expertise within the field, teaching a wide array of technologies including programming, electronics, augmented and virtual reality, real-time 3d, machine learning and AI.

In terms of embedding these changes, we integrated the stations fully into the curriculum, especially in the first two years. We have evaluation weeks called ‘driving development weeks’ where tutors and technicians plan the further programme together with the department faculty. This constant dialogue helps us embed relevant technologies into our education: most tutors have their own artistic or design practice and are thus very aware of recent technological shifts and relevant discourses. Beyond mere technical facilitation, we also try to introduce contemporary impulses in more formalised study programmes. However, this is an area that still needs better definition. Many of these practices are not material- or technology-based but rather socially oriented, participative and collaborative. Technology plays a different role in these kinds of practices.

It’s interesting to reflect on this. The challenges students face are not purely technological, so the tools you provide to address them also have to include skillsets and instruments from entirely different realms. In your 2018 essay,[2] you hinted at the necessity for a more holistic approach, stating that the stations are only one of several measures to implement a broader shift in teaching at the WdKA, where conceptual, critical and theoretical approaches are being given centre stage instead of artefacts, where processes, not products, are the main concern. How has the stations’ introduction been received by students and teachers? Did they embrace the epistemological shift thus enacted?

Yes, this shift has been significant and transformative. Over the past decade, we have worked diligently to embed this new approach within our major disciplines, and the results are evident. One notable example from last year is an exhibition by first- and second-year photography students. Drawing on the interaction station, they worked on a project focusing on the relation between photography and memory, which spanned around five to six weeks. This project required them to conceptualise and rapidly prototype their ideas. Collaboration played a crucial role here, with Boris Smeenk and Brigit Lichtenegger, colleagues specialising in machine learning and AI, guiding the students. They provided them not only with tools but also with critical reflection on these technologies, enabling a deeper connection to the concept of memory. The outcome was remarkable, as students integrated AI into their projects, showcasing their ability to think conceptually and produce tangible, innovative results quickly. This blend of reflection and making is a testament to the success of the stations in fostering a hands-on, critical learning environment.

Despite these successes, much remains to be done. If ten years ago it was important for academies to engage with interdisciplinarity and breaking through the arbitrariness of art and design silos, today’s urgency is forcing higher education to look beyond its institutional walled garden. Today’s most pressing challenges around ecological challenges, including climate breakdown, pollution, biodiversity loss and the related human and nonhuman injustice associated with this, are forcing us to reconsider the way we teach material practices. For the stations in particular the question arises, how do you bring circular, regenerative or climate-adaptive design into practice? This is not so much about technology, but about quality. Within all these urgent topics, it’s very much about our material practice. If you think about working with textiles or yarn, for example—where does this yarn come from? What is the history of how we work with yarn? Material practices are so political and social. We are still struggling with this. Many students do reflect on this, but it is hard to make this translation from reflection into practice. It can also be paralysing. Can you still make things in this world, given that it is already oversaturated with all kinds of stuff? To me, this is a very valid question.

Could you elaborate on how the stations are embedded in the school’s curricula, and vice versa: how are the curricula being adapted to make use of the stations?

The stations are integral to our curriculum and serve two main roles. Firstly, they are embedded in the curriculum, offering courses and projects across different programmes (within disciplinary programmes, majors, and practices, the interdisciplinary programmes). We meticulously plan each year to ensure the stations are involved in numerous programmes, ranging from eight-week courses to shorter, introductory sessions. The stations organise their own instruction programmes and electives, which focus on specific skills and the application of new technologies. Secondly, we support research through making, with blogs or wikis[3] to aid students in their projects. This comprehensive approach ensures that the stations are not only places for technical execution but also for critical reflection and knowledge sharing.

How has the introduction of the stations affected the distribution of labour and hierarchy among the school staff?

The stations have significantly altered the traditional hierarchy between technical staff and teaching staff. Before 2012, our workshops were primarily technical spaces staffed by instructors and technicians who were not involved in developing educational programmes. However, within the stations, we have integrated teaching and technical roles. We still have technicians who focus on machine operations and instructions, but we also have tutors who teach and reflect on technologies. This creates a more inclusive environment where teaching and technical expertise coexist. Although defining these roles clearly has been challenging, we aim to ensure that both instructors and teachers have career development opportunities. Despite recent salary scale adjustments that have created gaps between roles, we continue to work towards fair career prospects for all staff.

You have previously cited the historical Bauhaus as a major influence on the institutional reform processes at the WdKA, of which the stations were a crucial part. Where do you see the strengths of that school’s pedagogical model, and where do you see shortcomings?

The Bauhaus legacy is crucial for our approach, particularly with its emphasis on integrating contemporary technology into education and its collaboration with industry. The Bauhaus excelled in adapting to technological advancements and translating them into educational programmes. Their focus on material experimentation, even with limited resources, and their commitment to social change are highly relevant today. However, the Bauhaus also had considerable limitations, as Hicham Khalidi pointed out in an essay in response to the New European Bauhaus project, particularly when looking at its role in supporting capitalist production and its detachment from sustainable practices.[4] We strive to address these shortcomings by fostering a more sustainable, inclusive and socially responsible approach to art and design education.

Looking ahead, where do you see the stations in another ten years?

I envision the stations playing a critical role in advancing digitalisation and sustainable practices. Teaching students to engage with circular, regenerative and climate adaptive design is essential. We must move beyond theoretical discussions and being discursive; instead, we as educators should demonstrate practical applications. This requires transdisciplinary collaboration with scientists, social workers and other experts. One proposal is to establish learning environments within the city, collaborating with organisations and communities already engaged in sustainable practices. By doing so, we can offer students hands-on experience and actionable insights into making tangible changes. This approach aims to empower students to contribute meaningfully to addressing climate change and other urgent issues through practical, innovative solutions.

is a senior lecturer at the Willem de Kooning Academy (WdKA), Rotterdam University of Applied Sciences. In this position she is responsible for educational development and research within the field of new making practices relevant for art and design education at the Willem de Kooning Academy. She also coordinates professional and educational development, develops policies and supervises research through making within the WdKA stations.