Technology, democracy and UTOPIA: Scandinavian participatory design in the making

Could more knowledge about emerging technologies give trade unions more influence on working conditions and enhance workplace democracy? Could seemingly restrictive technologies be designed through engaging a broader variety of people in the design process? These questions were central in the 1980s research project UTOPIA, in which the Nordic Graphic Workers’ Union together with researchers focused on how to actively influence the digital transformation of graphic work as computers were introduced in newspaper production.

This Scandinavian project explored the design and development of new computer-based tools for image and graphic work. It also drove the formation of values, methods and approaches that are still very much at the core of Scandinavian participatory design. The development of new design practices was fuelled by an ethos of democracy and political activism, engaging people as experts of their own experiences in processes of collaborative designing. Core participatory design methodologies today still carry strong ideals of democracy, deliberation, contestation and collaborative learning, shaped in these early intersections of technological innovation, socio-political activism and intervention made possible by work life-related legislation. In the Nordic countries, this type of ‘cooperative design’ evolved in a legal and political context in which trade unions and researchers collaborated with the aim of supporting workplace democracy when developing IT systems.

In Sweden, legislation introduced in 1976 stated that trade unions had the right to influence any changes and decisions affecting workplace conditions. During the 1970s, computers were beginning to make their way into many work sectors, radically changing the organisation and content of many professions. Employers saw the promises of efficiency and lower costs as digital tools could streamline production and enable the hiring of unskilled workers to carry out work previously done by expert workers. The trade unions, on the other hand, saw the new technologies as a potential threat and strove to safeguard the expertise of skilled workers in the digital transition. Since the legal conditions postulated that unions and industry leadership were obliged to negotiate such substantial changes, this led to the situation that unions, managers and computer developers actually had to negotiate how new digital systems and tools should be designed.

Nordic labour unions mobilised to find ways of understanding the computer technologies. This was crucial to figuring out what kinds of developments to aim for and which to try to avoid from the workers’ perspective of safeguarding jobs. Trade unions reached out to researchers who were familiar with computers, and researchers in the fields of computers and social sciences welcomed the opportunity to engage with expert workers in different fields to better develop computer-based tools for different contexts. In the 1970s, such knowledge-oriented projects were the Norwegian Iron and Metal Workers Union NJMF project in Norway (1971–73), the Swedish DEMOS (Democratic systems for steering, 1975–79) and the Danish DUE (Democracy, development and Electronic Data Processing, 1977–80). A new space for designing tools and work flows was thus offered through a combination of the new technologies and the work-related legislation, leveraged by trade unions and researchers with the aim to mutually learn from each others’ expertise. When the UTOPIA project was initiated in 1980, it built on new methods for mutual knowledge sharing and took further steps towards developing ways of not only learning but also designing together.

UTOPIA[1] was a project that ran actively between 1981 and 1985 in the context of newspaper production, initiated by the Nordic Graphic Workers’ Union. In the transition from manual layout and typesetting to computerised tools for image, text and graphics, the union aimed to steer the development of new tools towards safeguarding and enhancing the work of skilled graphic professionals. The sites for the project were the Swedish newspaper Aftonbladet and the Danish Information, funded by the Swedish Centre for Working Life (Arbetslivscentrum), with technology support by the computer supplier Liber/TIPS.[2] The project engaged researchers from Sweden and Denmark in collaboration with union leadership and skilled graphic workers for the joint development of computer-based tools for text and image processing, and of training and knowledge-building practices and materials for digitized graphic work as well as for work-place negotiations and organisational changes.

In the UTOPIA project, researchers in computer science and social sciences inspired by action research, as formulated in the ‘critical pedagogy’ by Paulo Freire in Pedagogy of the Oppressed in the late 1960s, actively sided with unions and workers as opposed to management. This was an expressly emancipatory ambition to change the power structures in the workplace by empowering workers in the design of and decision-making on technologies bringing about changes in working conditions.

A central issue in UTOPIA was to find methods to support mutual learning between computer technologies and the often tacit knowledge and embodied skills in typesetting, image processing and graphic work. This was crucial to be able to jointly imagine and design what a computer-aided workflow could be like. A break-through in this came when prototypes and mock-ups were introduced as ways to support envisioning and enacting future practices.

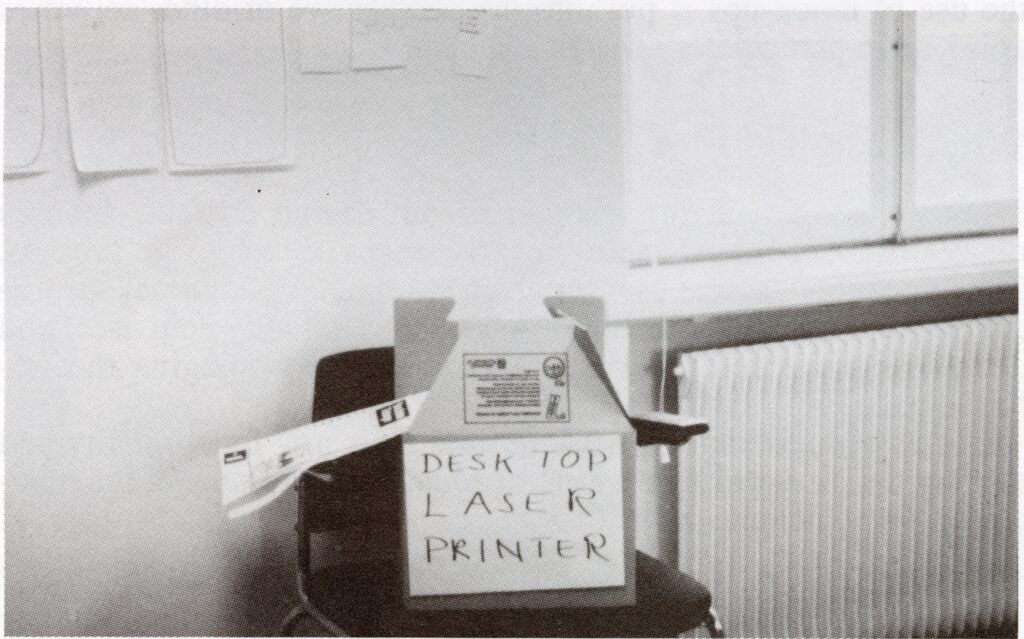

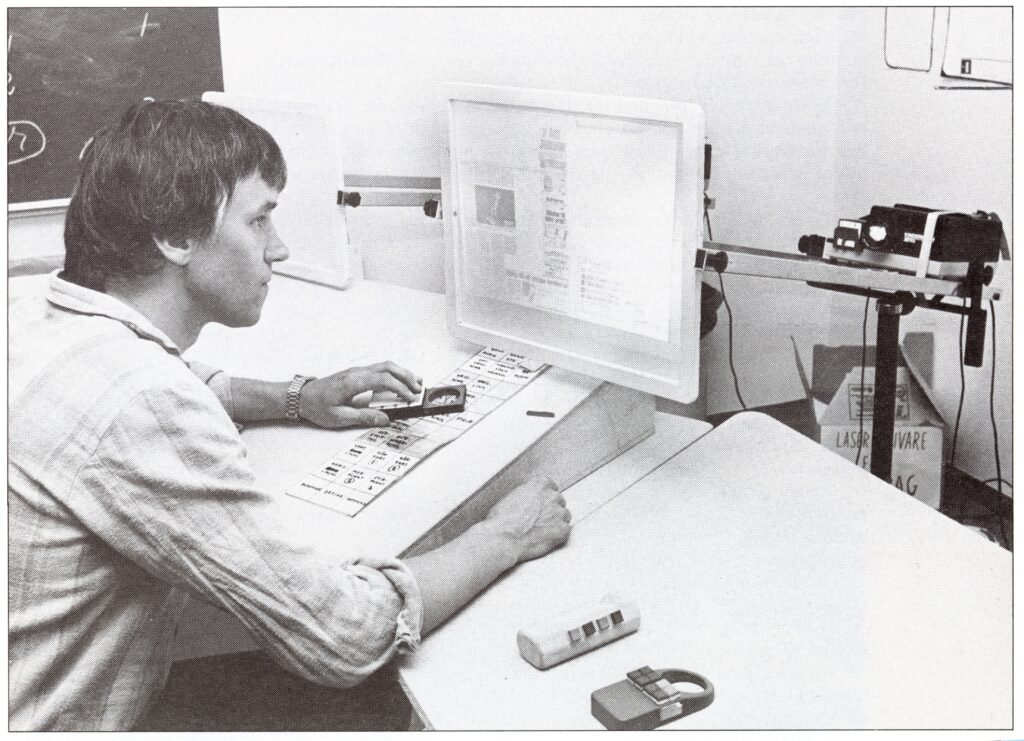

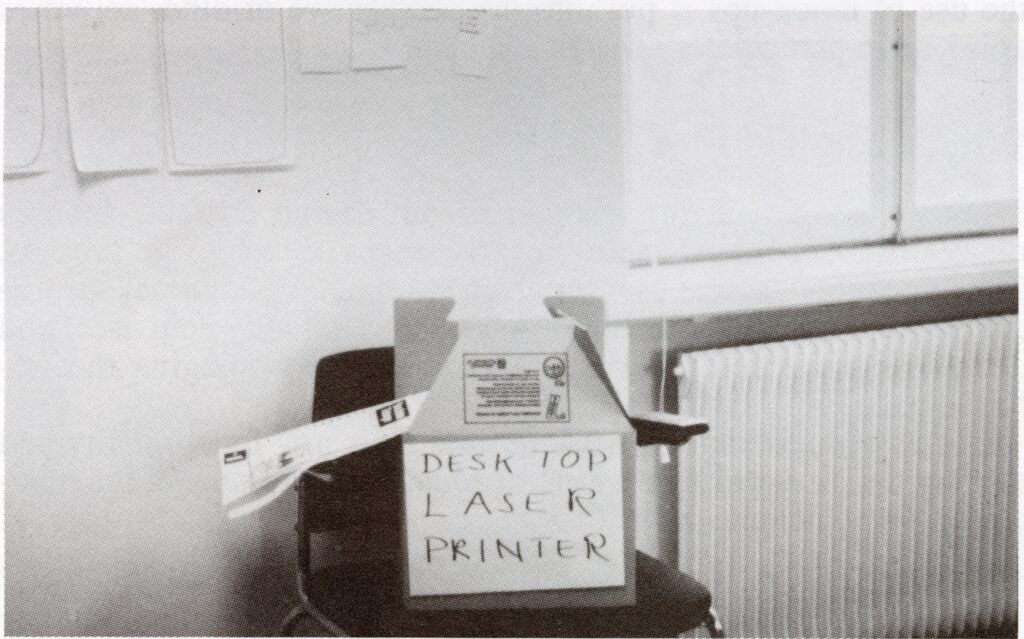

To probe what future computer-supported graphic work might be like, UTOPIA introduced the concept of the technology laboratory to ‘be able to work as though the new page make-up and image processing technology already existed’.[3] Mock-ups of computers, screens, interfaces and support tools were introduced from 1982. Making use of simple materials such as cardboard boxes, hand-written paper labels and slide projectors, future screen-based graphic work could be represented.

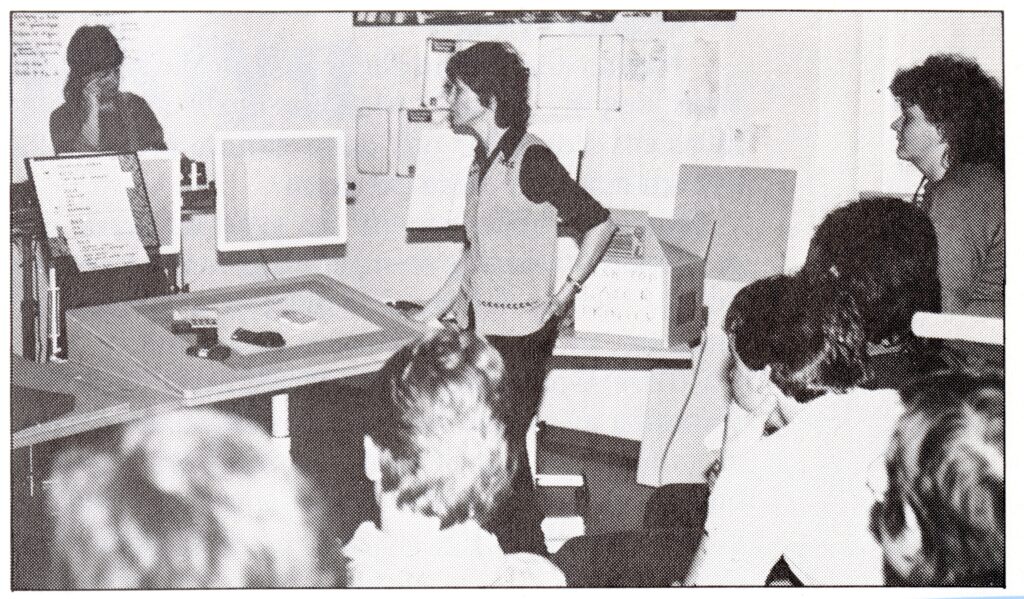

As prototypes and mock-ups were introduced, they supported deliberation and design. These experiments enabled in-depth discussions and decisions on how not-yet existing computerised tools and workflows might be applied in various stages of graphic work.[4] Through the physical representations, it became possible to share knowledge and imagine what might be possible, plausible and preferable in the development of digital tools for skilled workers – and how to argue for this from a trade union position of negotiating workplace politics and power.

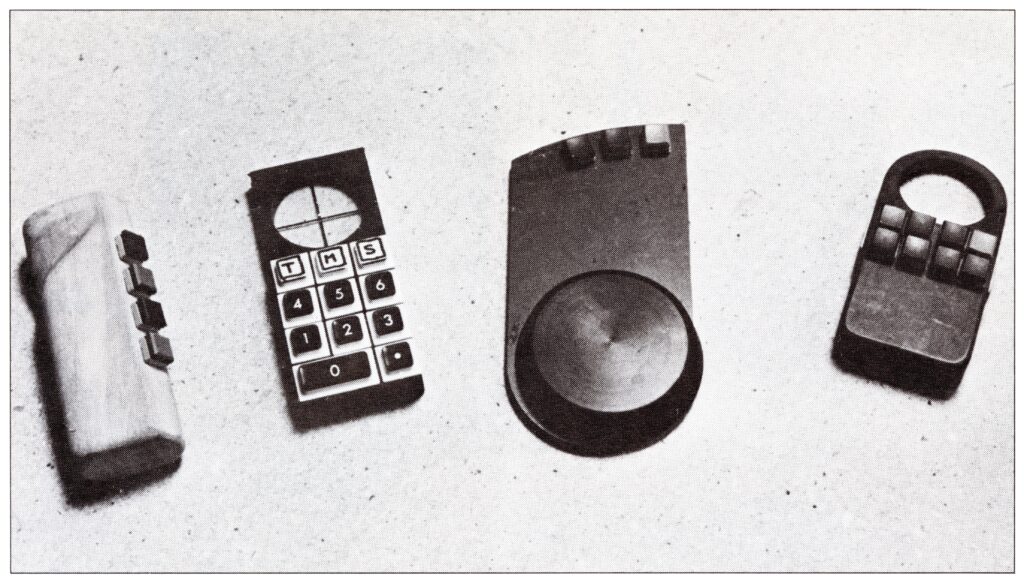

Screen-based work was tried out through cardboard mock-ups simulating how digital documents and images might be handled. Prototypes of pointing devices were developed – alternatives to what was then already known as ‘the mouse’ – together with other rough or detailed representations of tools and work methods. Hands-on engagement with the mock-ups and prototypes allowed designers, computer researchers, graphic workers and journalists to jointly enact future situations and actions as a basis for further explorations and for making joint design decisions. This supported ways of designing interactive systems and tools through showing, testing and discussing different possibilities together. Through enabling sharing and negotiating design decisions, the expertise of many different people became weighted into a holistic and ongoing design process.

As ideals of democratic deliberation and co-determination were strong in this emerging collaborative development practice, designing became a democratic responsibility shared between ‘designers’ and ‘expert users’. New participatory methodologies pushed a reframing of designers’ roles and responsibilities from individual artistic form giver to collaborative coordinator of a democratically infused design process. Participatory design thus also allowed for broadened understandings of what a design outcome could be.

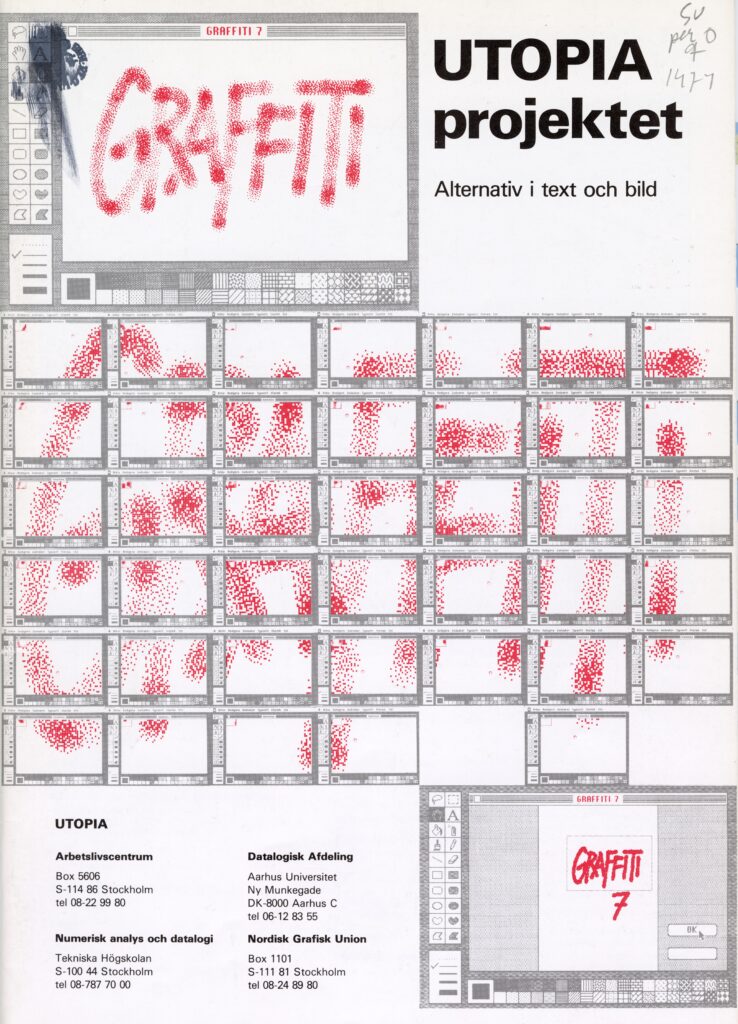

Designing digital tools for graphical layout work was of course one tangible outcome of UTOPIA, leading to the design of specific products that could be manufactured and materialised. But equally important was the dissemination of knowledge about digital graphic work during and after the project. The final project report, the seventh in a series of reports called Graffiti, was made available in many languages: Swedish, Finnish, Danish, Norwegian and English. The report was printed in 45,000 copies, spreading insights into how to use new digital tools, how to set requirements for their development, how to organise a work-place deliberation to influence computerisation. This was framed as a potential ‘new Scandinavian model’ for technological development, in which unions could and should play an important role in finding alternative solutions and technological applications and in influencing ‘the future development of new systems’.[5]

The development of Scandinavian participatory design took place in the intersection of technological development, action research and workplace democracy. Researchers in UTOPIA hoped that the design and development of computer-based tools and work methods would also empower the fight for employment security and the value of human expertise and skill in a context of increasing computerisation and automation.

The deliberative spaces provided by work environment legislation strengthened the Graphic Workers’ Union’s position both in influencing the design of new tools and in safeguarding jobs for their members in times of great technological change. Defining design requirements for digital tools that supported and enhanced skilled graphic workers’ profession became UTOPIA’s counter proposal to the employers’ ambitions which the unions feared were taking a turn towards developing digital layout tools which could easily be used by almost anyone, devaluing the skilled graphic workers’ profession as well as their wages. The union’s strategy effectively turned to excluding non-skilled workers from entering the graphic design or newspaper printing profession through the design of digital tools for expert users.

While this Scandinavian model for union-driven negotiation and design in the 1980s substantially challenged notions of power, work, design and technology, there was no critique by UTOPIA towards the overall framework of industrial progress and increasing production. Rather the contrary is true: unions’, researchers’, employers’ and technology developers’ hopeful views of an industrial future were well aligned. As stated in the final UTOPIA report, the new Scandinavian model aimed at ‘combining objectives like good working conditions and industrial development and, if possible, increased exports’.[6]

The design practices developed by UTOPIA were shaped by aims of strengthening workplace democracy, social justice and deliberation – and equally by ambitions of supporting economic growth, technology-driven efficiency and industrial expansion. Today, design practices adhering to Scandinavian tradition have also moved beyond addressing the uses and applications of technology at work and into socio-political contexts aiming to support civic action and activism, and planetary issues of justice and sustainability transitions.

Post-industrial challenges and more-than-human outlooks[7] call for prototyping new ways of designing together, beyond values of linear progress, efficiency, extractivism and human exceptionalism.[8] Doing this requires shedding light on the ideas of human-centred democracy and techno-industrial progress that once sparked the formation of core participatory design methods and approaches. Making visible the values and methodological constraints historically embedded in participatory design allows for swerving and shifting towards directions that might better respond to designing after progress.[9] Other kinds of futures could then be possible to glimpse, revealed through expanded understandings of what participation in design might be if humans and other entities – biological, geological and technological – could creatively and collaboratively negotiate and explore how, what and why they design together.

is associate professor in design history and design theory at the Umeå Institute of Design, Umeå University, with a PhD in industrial design and previous studies in the history of science and ideas. She is part of the artistic research environment ‘Design after Progress: Reimagining design histories and futures’ (project number 2022-02319). Göransdotter works in the intersections of historical and practice-oriented design research, exploring how ‘transitional design histories’ can work as prototypes for unpacking and reframing core concepts in contemporary and emerging design practices. By making present the historicity of designing, assumptions and ideas embedded in design categories, concepts and practices can be constructively destabilised and support explorations of ‘designing otherwise’.