The role of technology at VKhUTEMAS: Psychotechnics, combinatorics, and objective foundations

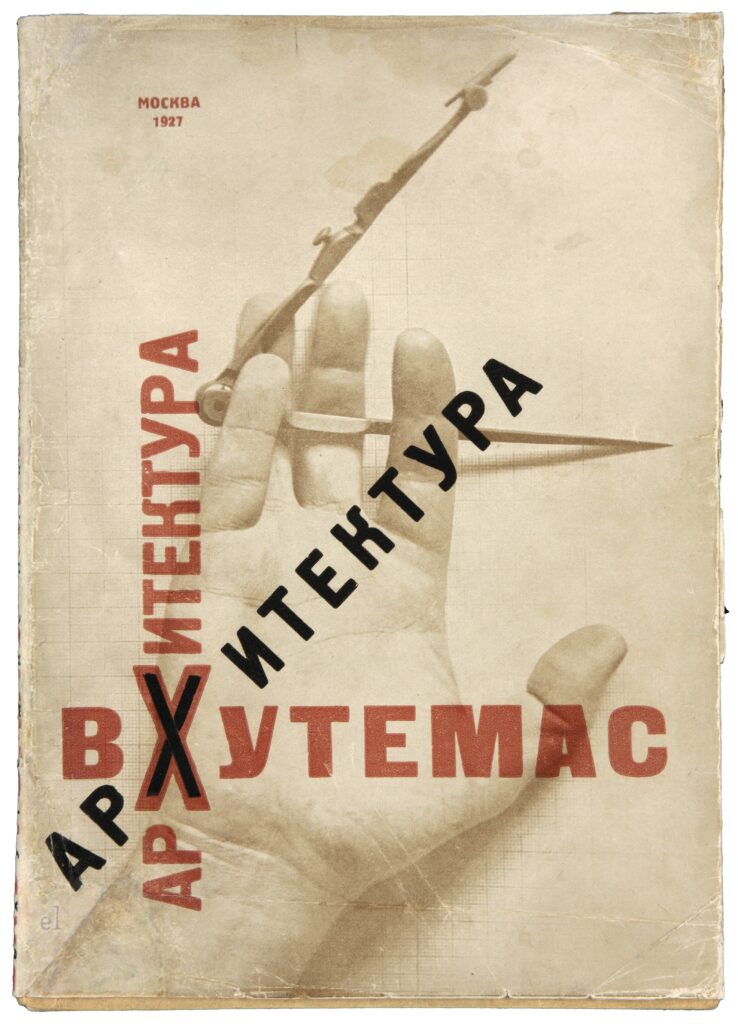

Education and experimentation were closely intertwined at the Higher Art and Technical Studios, known as Vkhutemas—an interdisciplinary Soviet design school, active between 1920 and 1930, which drew on the technological advances, scientific achievements, and artistic experiments of its time. While similar to the Bauhaus in its experimental spirit, the student body of Vkhutemas was over ten times larger than its German counterpart. With an enrollment of nearly 2,000 students, it was an unprecedented modern undertaking.

The challenge of educating “the masses,” while simultaneously reconceptualizing art and architecture as modernist disciplines, required a coherent pedagogical approach grounded in a new kind of systematic methodology. The goal of such approach was not only to make learning design accessible but also to break free of the exclusivity of “creative genius” as well as from the centuries-old academic traditions, such as the classical canon.

Vkhutemas faculty and students sought to resolve the proverbial opposition between “science and creativity” by applying the conceptual apparatus of experimental psychology, theoretical physics, and even mathematics to problems of design. The most notable outcomes of this exchange were the development of a “psychoanalytical” or “objective” method in design and an establishment of a Psychotechnical Laboratory by the Vkhutemas professor and architect Nikolay Ladovsky. While undoubtedly familiar with the namesake method in psychology, Ladovsky appropriated the Freudian term “psychoanalytical” somewhat liberally, focusing on perception of spatial form rather than on the inner workings of the mind. Its use can be interpreted as developing an architectural version of the theory of the unconscious, where like the famous psychoanalyst, the architect sought to bring the sphere of the unconscious into the sphere of consciousness by transferring the sensations evoked by spatial form from the realm of the psyche to the realm of architectural knowledge.

Transferring these intuitions from the realm of invisible into abstract spatial categories would make them not only visible but also manageable and eventually measurable. In addition, it would ostensibly offer insights in the opposite direction—“the impact of architectural form on a psyche”— after all, according to Ladovsky’s colleague at Vkhutemas, Nikolay Dokuchaev, “certain colors, shapes, etc., have certain patterns that evoke certain sensations in the viewer.”[1]

The principle of economy of psychic energy or “the energy of perceiving while experiencing the spatial and functional qualities of a building” was central to Ladovsky’s conception of architecture as science—an approach he conceived of as “rationalist.”[2] One of the goals of “ratio-architecture” was to reconcile real-life perception of spatial form with its representation. In Ladovsky’s opinion, disciplinary drawing conventions, such as plan and elevation, traditionally used by architects to describe spatial form did not reflect the way that form appears to the eye in three- and four-dimensional reality. In other words, while two-dimensional orthogonal projections give a “precise” representation or idea of an architectonic object, its “real perspective” only provides an approximation. Thus, relative perspectival view should seek to achieve its absolute geometric “limit,” expressed orthogonally.[3]

Ladovsky saw an architect’s mission in bringing closer the geometric expression of a form, which “we always perceive in perspective,” to its intentional image provided in its projections. The rationalist doctrine, therefore, aimed to mediate this discrepancy by articulating or expressing essential properties of form, so that the eye registers these as “defined values.”[4] Ladovsky described this condition in terms “the highest technical human need for orientation in space,” which can be interpreted as understanding space as a measurable entity.[5] Envisioning and constructing architectural form, therefore, can become an objective process, defined by a set of “compositional and organisational laws” and guided by operational algorithms.[6]

This was something that Ladovsky and his colleagues investigated in their foundational course called “Space” and at the Psychoanalytical Laboratory of Architecture at Vkhutemas.[7] Ladovsky first mentioned the need to set up such a laboratory in 1921 at the Institute of Artistic Culture (Inkhuk), founded by Wassily Kandinsky, but was not able to realize it until 1927. Modelled after “(t)he famous psychologist [Hugo] Münsterberg,” the Psychotechnical Laboratory embodied the development of a conceptual apparatus for the new, i.e. modern, architecture.[8] Ladovsky believed that “(e)ven if only on an elementary level, an architect must be familiar with the laws of perception and the means by which it operates, in order to utilize in his practice everything that contemporary scientific knowledge has to offer.”[9]

Among the various disciplines facilitating the development of architecture as a science, he claimed that ‘a very serious place must be given to the still-young science of psychotechnics’.[10] ‘The works produced by me and my colleagues at Vkhutemas starting in 1920 in the field of architecture’, writes Ladovsky, ‘tested by methods of psychotechnics, would help the scientific establishment of an architecture based on rationalist aesthetics’.[11] This research aimed to ‘raise the veil of mysterious creativity’, in other words the veil of the unconscious, from architectural labour.[12] Soviet architects saw science, in this case psychoanalysis and applied psychology, as a basis for reforming both the disciplinary and formal foundations of architecture. Laboratory work was framed as a means of converting architecture from an elitist and unscripted artistic practice, then still entangled in a myriad of historicised styles, into an objective, scientifically grounded field. Ultimately, it sought to quantify ‘design talent’ based on the ‘German and American systems of measuring general abilities’ and to codify the organic matter of human perception into a set of laws guiding the design process.[13]

Ladovsky and his colleagues, most notably a former student Georgy Krutikov (the author of the New (Flying) City project), used the laboratory to test and train the professional prowess of students. In particular, they tested aptitude for spatial assessment, which was deemed essential for future architects. Perceptual psychology allowed them to draw a connection between the conception of spatial form and ‘experiential sensibilities’. Since the goal of the laboratory was to develop objective foundations for a theory of architecture as a science, its tests not only evaluated students but also provided the evidence for deriving universal principles of spatial form. Ladovsky and Krutikov sought to frame the problem of individual creativity in an ‘objective’ manner and to establish a productive reciprocity between design pedagogy and scientific research. Continuous feedback between teaching and testing units at Vkhutemas not only promoted innovation in design but also led to a leap in the development of modern space and form.

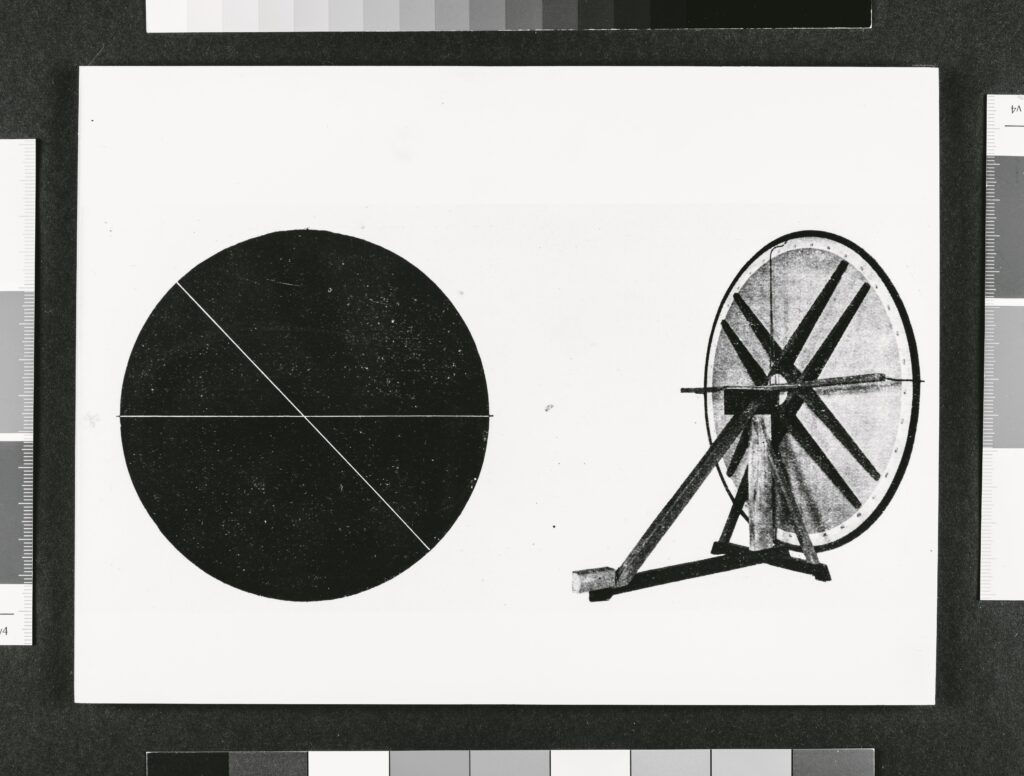

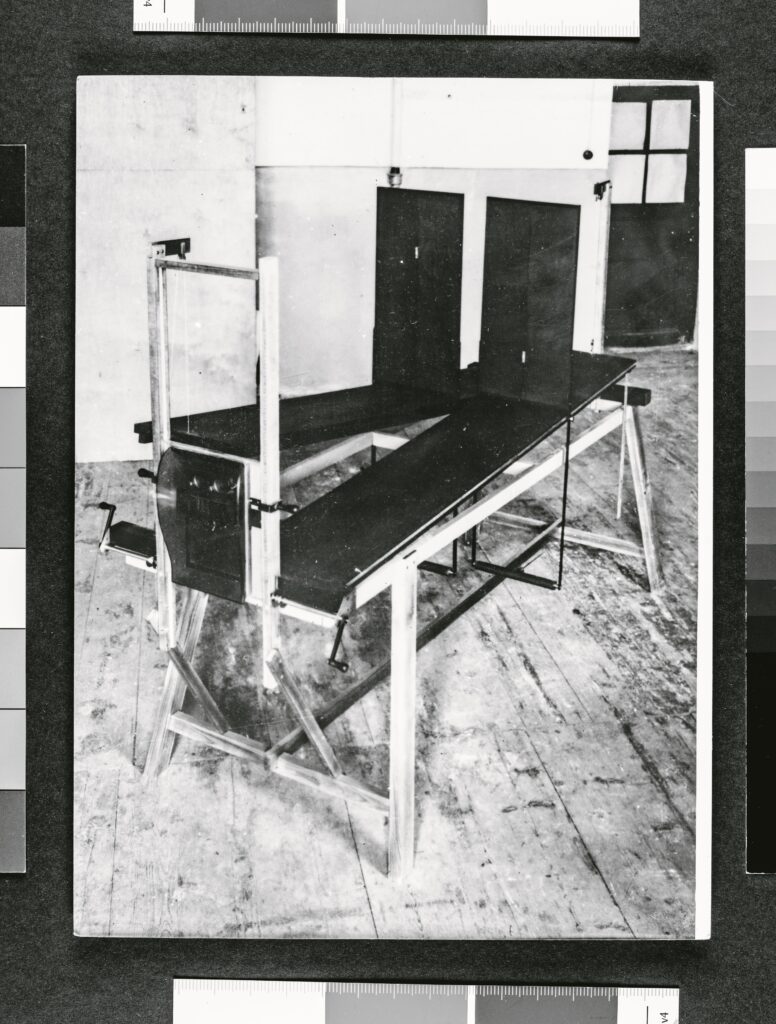

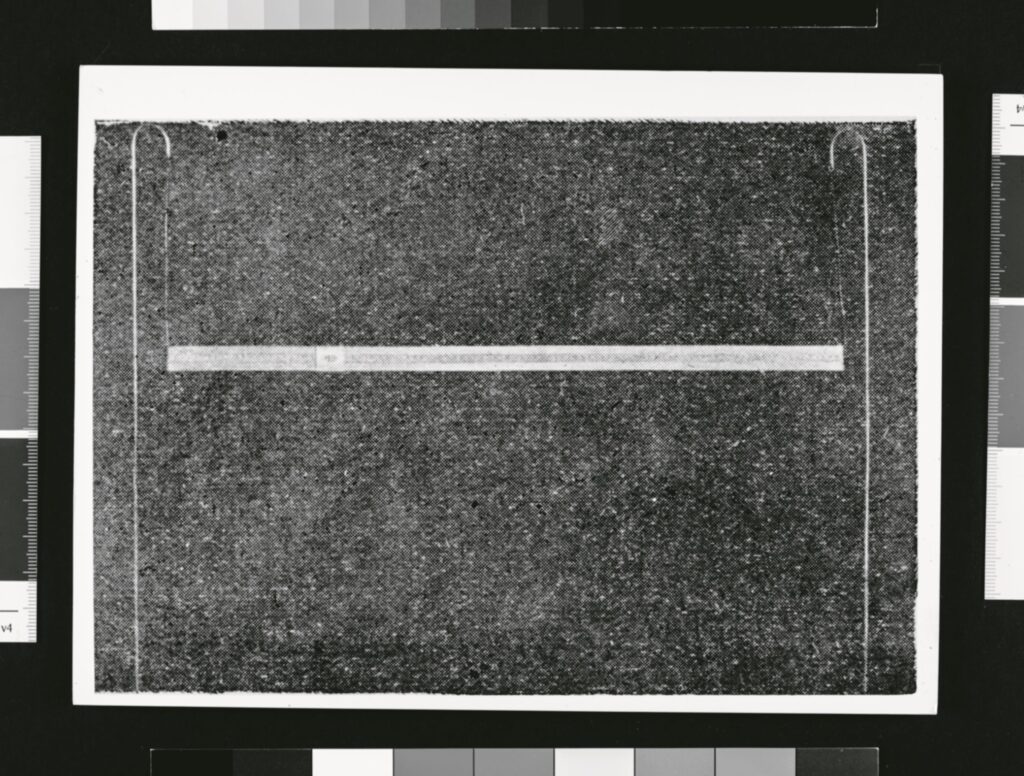

According to the “personal chart,” developed by Krutikov for recording “the psychological profile of architectural talent” of the students, the laboratory specifically tested for “attention, memory, accuracy of vision, spatial sensibility, spatial coordination, orientation, imagination, ability in spatial combination, and motor skills.” The tests were conducted using a set of instruments built by Ladovsky with his colleagues and students. The measuring function of the instruments was encoded in their name, ending in glazometr—literally “eye-meter.” The simplest one, the line-eye-meter (li-glazometr), measured the subject’s ability to divide a line into specific increments, e.g., in half or in quarters. The angle-eye-meter (u-glazometr) measured the ability to identify an angle as straight, 30-degree, 45-degree etc. The plane-eye-meter (plo-glazometr) tested the ability to identify which geometric figure of equal area—a square or circle—appeared visually larger. The volume-eye-meter (o-glazometr) studied the relation of volume to shape, or how glass vials of equal volume but different shape would appear to the eye. The space-eye-meter (prostro-metr), an apparatus that was arguably the laboratory’s most significant invention, was designed to measure the perception of spatial depth relative to an incline. It required that subjects identify relative distances within groups of geometric forms set on surfaces positioned at different angles, as well as the perceptual properties of forms relative to their position in space.

After receiving the first results of the Psychotechnical Laboratory experiments, Ladovsky announced an ambitious goal to “propose a creative foundation for architecture as science” by applying the combinatorial theory used in mathematics as a design method. Research on “spatial combination” developed under Ladovsky’s direction by the laboratory’s head, Georgy Krutikov, aimed to systematize all basic compositional combinations of geometric shapes in space. Krutikov’s first step was to link the study of “the ability for spatial combination” with the study of “a sense of spatial composition.”[14] This was a critical step, connecting an emerging algorithmic approach to design, offered by combinatorics, with a traditional time-tested academic notion of composition. Once that relationship was established, it was possible to focus on spatial combination as a variety of possible arrangements of shapes (flat or volumetric) relative to each other in two and three dimensions.

The rationalists sought to develop a comprehensive system for testing future architects, one that would involve not only psychotechnical but also mathematical scholarship. The application of a combinatorial approach in psychoanalytical research would enable, according to Krutikov, “the establishment of a series of tests, defining, on the one hand, the creative ability of the tested subject, on the other, his aptitude for spatial combination.”[15] Using mathematical “theory of connections” formulas as a basis, Krutikov deduced his own “theory of spatial combination.” This theory would account for all possible spatial permutations due to the various positions of connections in space, as well as for the possibility of rotating each figure around its center of gravity.

Krutikov developed two types of combinatorial tests: one for measuring “creative capacity” and the other corresponding to the ability for spatial combination—or, in other words, the potential of systematisation. In developing the tests, he decided, however, to limit the number of combinations by keeping the orientation of all figures at a 45-degree angle relative to the coordinate system, to make it manageable. In the first set, the subject was given several elements without a time limit and was asked to draw all possible combinations. For this set of tests, the percentage of missing combinations relative to the total number of permutations was an important measure of each student’s ability. The second set imposed a time limit. These types of algorithmic calculations and proto-machine learning processes, developed at Vkhutemas in the 1920s, anticipated the emergence of computational technologies that would become reality in a few decades.

Organized along two parallel tracks, the laboratory set out to develop testing techniques for future Soviet architects while seeking to distill objective laws of architectural form. These reciprocal research modes—one, which investigated the phenomena of space and form, and the other, which tested human perception of these phenomena—relied on active feedback between the scientific work conducted at the laboratory and its visible manifestation in the iterative pedagogical experiments performed in Vkhutemas design studios. Overall, these experiments and tests presented a compelling case of adapting a larger social mission to the field of architecture, which conventionally lay outside the measurable domain of industrial production. It also constituted a case of curious inversion, one in which the subjects of the study, i.e. the students, became the principal agents in defining the object of scientific investigation, namely architectural form. Deployment of psychological findings for design field was not a prerogative of Soviet educators alone—it was also being practiced at the Bauhaus, where a course on psychotechnics figured prominently in the school’s curriculum under the leadership of Hannes Meyer, and continued to be offered under his successor, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.[16]

is an architect, historian, and educator. She is a former member of the Center for Advanced Studies in Architecture (CASA) at the ETH Zurich and of the School of Historical Studies at the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) in Princeton. Anna served as a faculty at the Cooper Union, Parsons/The New School, City College in New York, at Cornell, Yale, Northeastern, and Harvard Universities. She worked as an architect and urban designer at OMA, NBBJ, Ennead, and the City of Somerville. Anna is a recipient of multiple awards, including Graham Foundation grants and the Mellon Fellowship. Her scholarly work has been published widely including by Log, IAS, The Journal of Architecture, Perspecta, Walker Art Center, and MoMA. She holds a Ph.D. from Yale University and an M.Arch from Harvard Graduate School of Design. Anna is the author of Avant-Garde as Method: Vkhutemas and the Pedagogy of Space, 1920–1930 (Zurich: Park Books, 2020) and Lessons from the Social Condensers: 101 Soviet Workers’ Clubs and Spaces for Mass Assembly (Zurich: gta Verlag, 2023).