Visual design in the military-industrial complex

In the mid-twentieth century, the crisis of the ‘two cultures’—the culture of art and the culture of science—became a fundamental debate in the academy and beyond. First diagnosed in lectures and writings by public intellectual C.P. Snow in the 1950s, the ‘two cultures’ problem articulated a conflict between the opposing outlooks of art and science, an opposition that Snow claimed would create not only intellectual confusion and institutional conflict, but also crisis across contemporary society.[1] The tensions between the hard sciences, defined by their cold and analytic worldview, and the subjective and humanistic approach of the arts represented profound social, cultural and political turmoil.

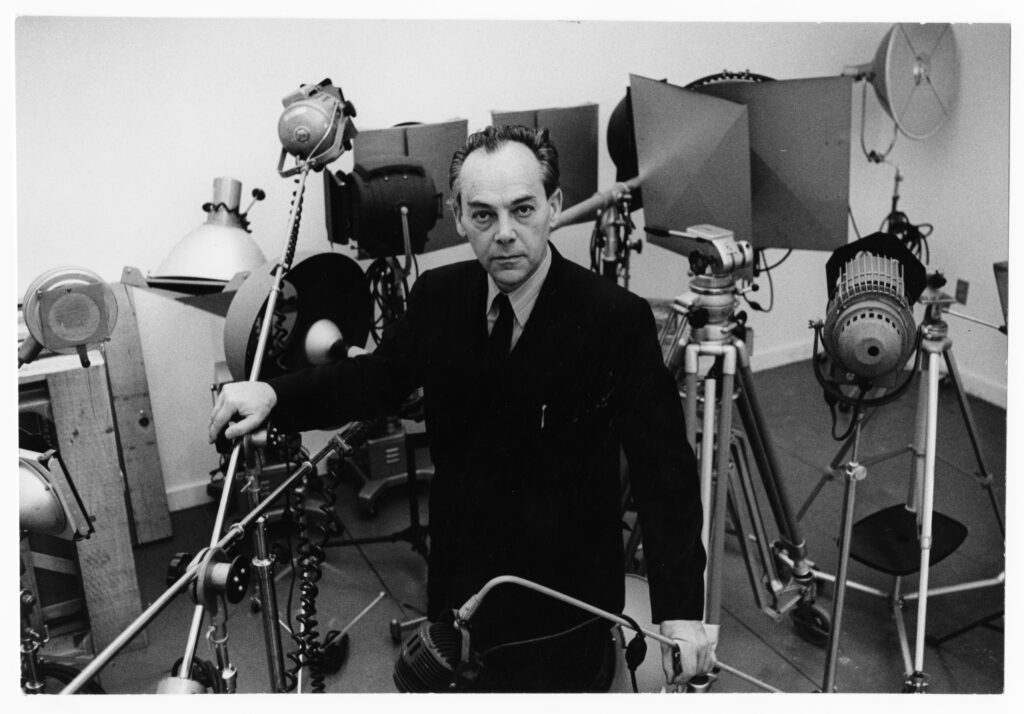

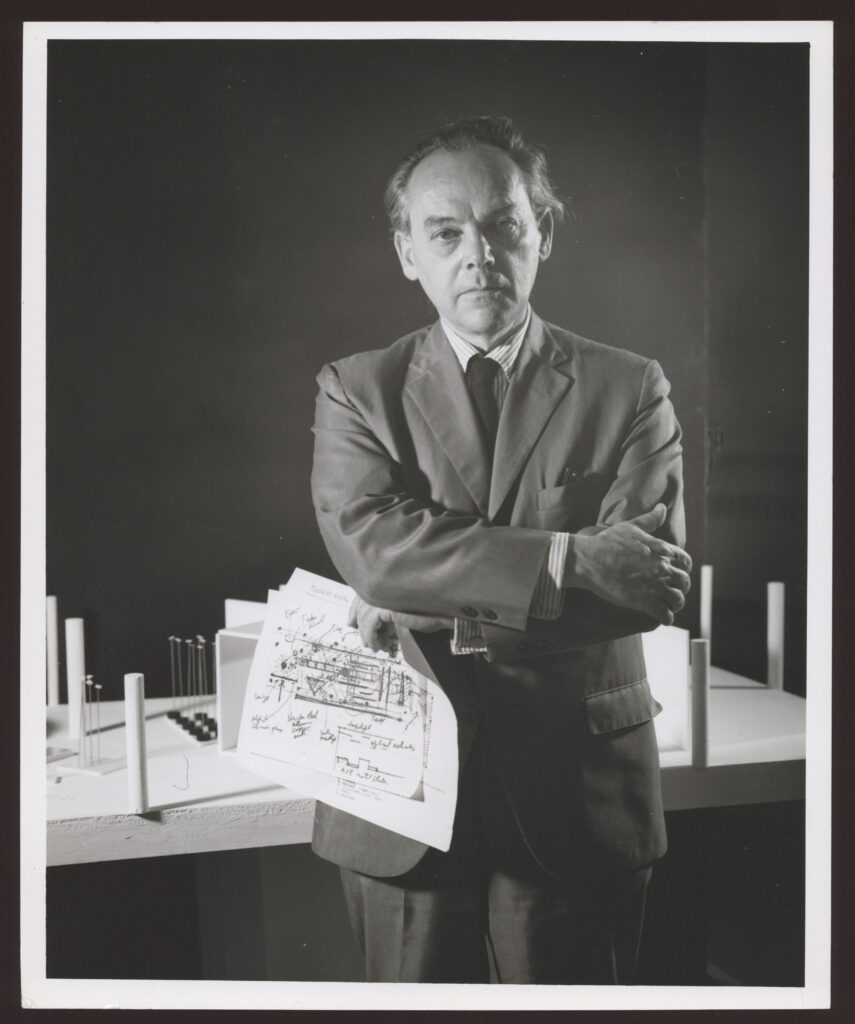

For the Hungarian-born American artist, designer and visual theorist Gyorgy Kepes, it was design—specifically what he termed ‘visual design’—that might reconcile the two cultures.[2] Visual design drew from the modernist design pedagogy first pioneered at the Bauhaus and then at the New Bauhaus (later Institute of Design) in Chicago, where Kepes taught from 1937 to 1942. It was codified in Kepes’s Language of Vision from 1944, a volume itself influenced by the famous Bauhausbücher (Bauhaus books) of the early twentieth century.[3] But Kepes’s programme found its clearest articulation after he began teaching at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1945. Here, at an institution dominated by scientific and technological study, his programme took on a new interdisciplinary agenda.

Visual design explicitly embraced what Kepes termed ‘interthinking’ and ‘interseeing’, the purposeful integration of ideas and images across divergent academic disciplines.[4] It borrowed from fields that appeared to have little to do with art and design and in this way mirrored the methodological approach of the systems sciences that defined mid-century, like the cybernetics of Norbert Wiener, the information theory of Claude Shannon and the general systems theory of Ludwig von Bertalanffy.[5] In the systems sciences, abstract concepts and general patterns created a universal language that might have relevance across disciplines, regardless of their specific application in a particular field.

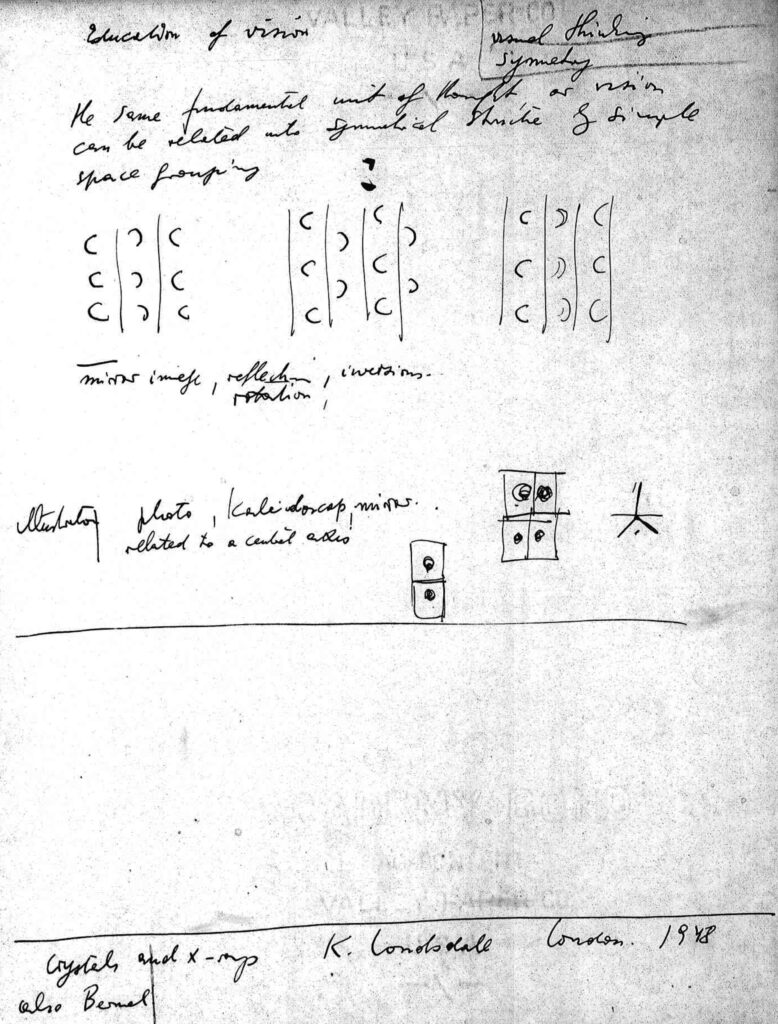

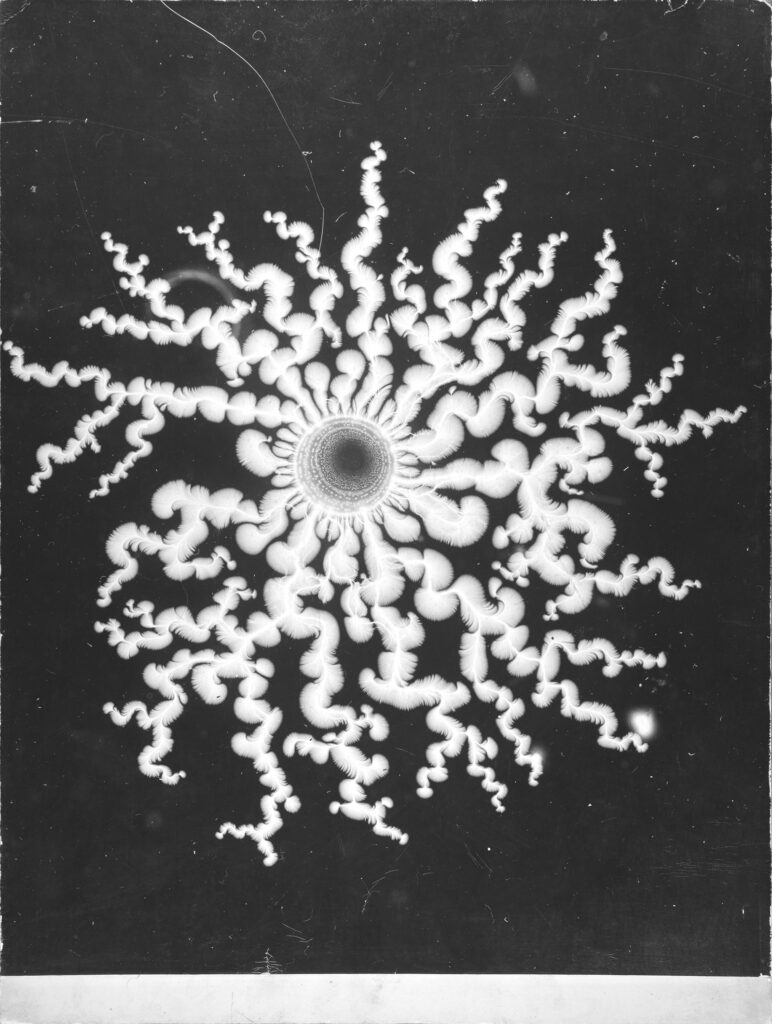

Kepes’s teaching notes are filled with examples of his approach to interthinking and interseeing. He studied such seemingly esoteric scientific sources as biologist Karl von Frisch’s 1950 study Bees: Their Vision, Chemical Senses, and Language, drawing conclusions about human perception from the way insects recognised simple shapes.[6] Diagrams visualising the arrangement of molecules in a crystal from a classic study by crystallographer Kathleen Lonsdale became maps for understanding the arrangement of visual patterns on a printed page.[7] The explosive bolt of the Lichtenberg Figure, an electric discharge studied by physicist Arthur R. von Hippel at MIT, became a key visual element that related a dizzying array of visual culture; its patterns of growth seemed to mirror the structure of works of art, from a Byzantine mosaic to a painting by Piet Mondrian.[8] These examples indicate how visual design created new forms of visual knowledge, new ways of seeing and thinking, by borrowing—sometimes illogically and often indiscriminately—from fields that have little or nothing to do with art and design.

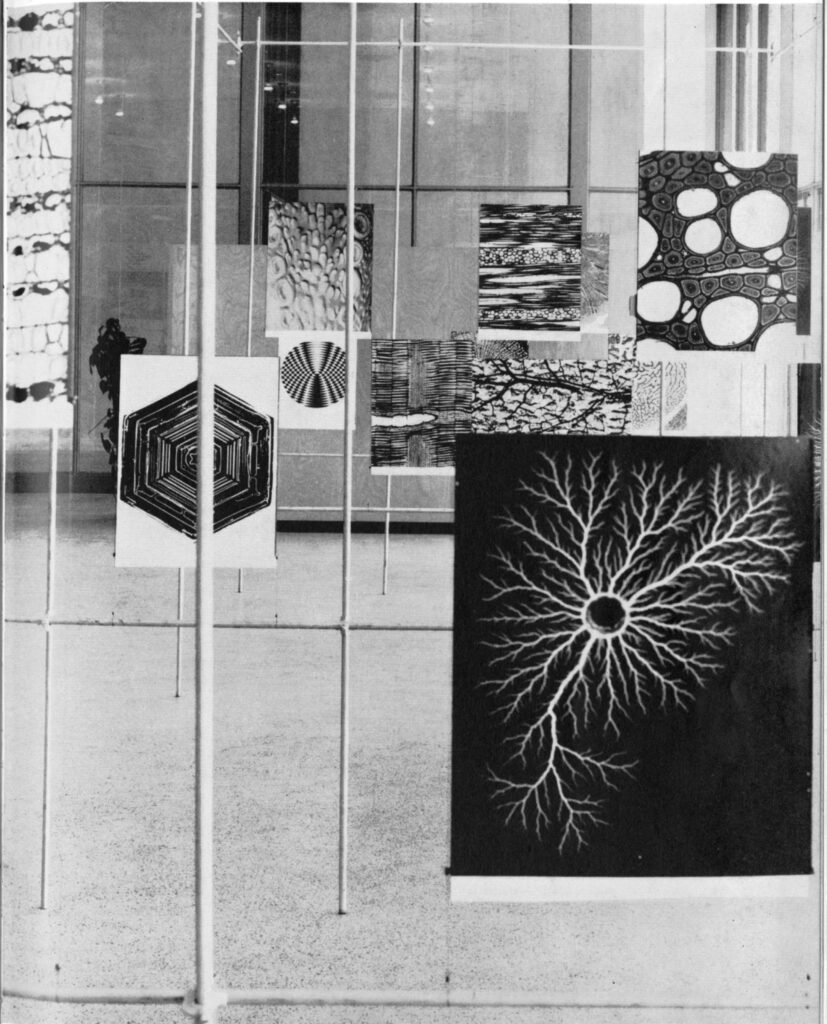

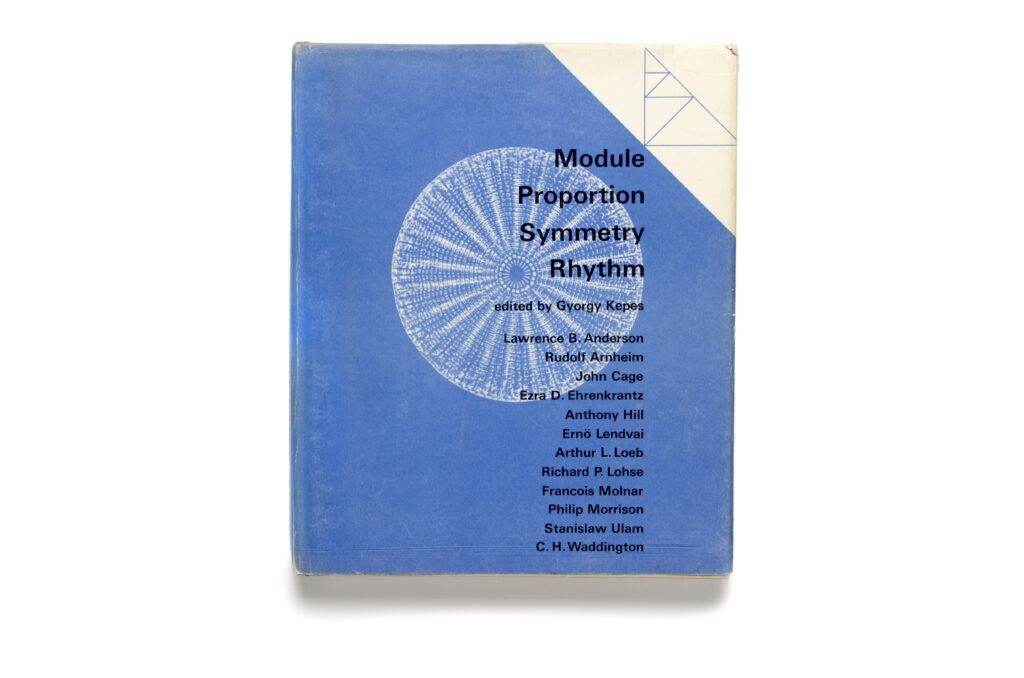

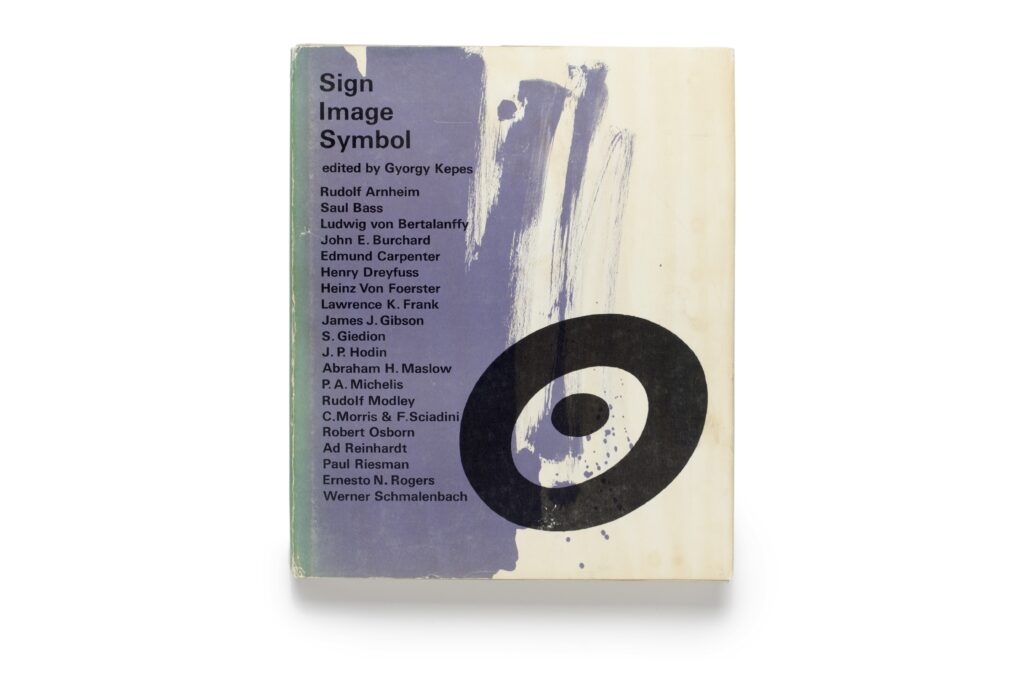

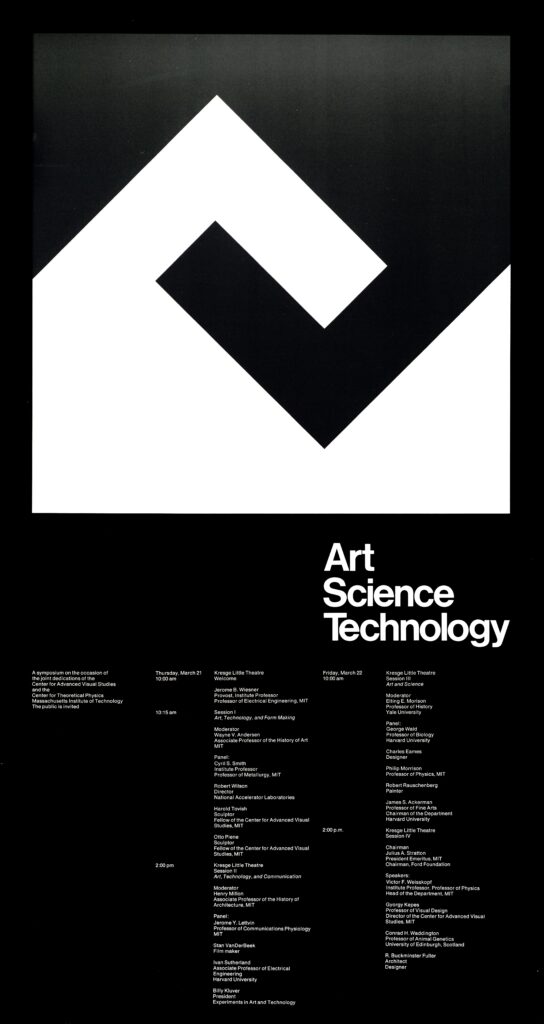

Visual design resulted in many unusual interdisciplinary projects. A 1951 exhibition titled The New Landscape attempted to demonstrate the connections between art and science through visual analogues, through common patterns seen in both artistic and scientific imagery. The show revealed a new world through the advanced photographic imaging technologies Kepes found in the laboratories of his scientific colleagues at MIT and Harvard. His series of Vision + Value books from the 1960s and early 1970s extended this approach through an editorial programme in which writings from major figures in both the arts and sciences were brought together around common abstract themes like ‘structure’, ‘motion’, ‘sign,’ ‘module’, ‘education’, ‘object’ and ‘environment’. While the resulting books were often perplexing for viewers—Kepes did not clearly explain the relationship between the authors and their divergent ideas, leaving the reader to make sense of a seemingly random collection—the result was nonetheless suggestive, offering readers a creative assemblage of provocative source material. The volumes quickly became standard pedagogical tools, found on art school bookshelves and course syllabi across the country, and were a regular feature of design teaching in the 1960s and 1970s.

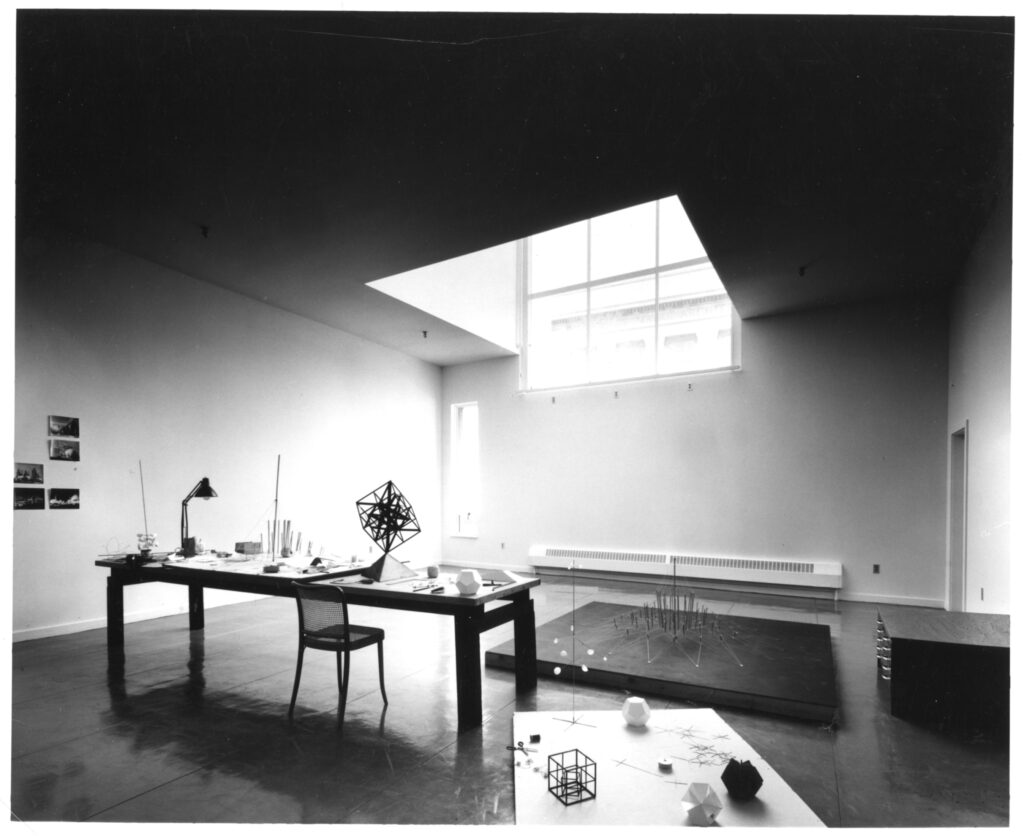

The Center for Advanced Visual Studies or CAVS was the final culmination of Kepes’s visual design programme, one that aimed to institutionalise his interdisciplinary ambitions at MIT through the model of the think tank. Based on templates like Princeton University’s Center for Advanced Study, CAVS aimed to facilitate collaboration by bringing artists to campus to work with scientists and new technologies. The idea has become commonplace—the artist-in-residence programme, now repeated at countless institutions—but at the time, it proposed a radical new approach to interdisciplinary exchange.

Interpreted generously, Kepes’s visual design programme and the fascinating projects it produced demonstrate how the humanistic values in the arts—creative expression, visual sensitivity and subjective aesthetic appreciation—might offer a compelling response to the cold, hard and objective worldview implicitly promoted by the sciences. The arts, in other words, might humanise science. Such a mission was of crucial importance at MIT, where scientific education was so dominant; MIT’s administration officially embraced visual design as a corrective measure, a way to balance the MIT student.

But seen more cynically, we can understand Kepes’s visual design programme as a compensatory project. By translating Bauhaus modernism into the idiom of MIT, Kepes effectively offered a humanistic, artistic, even altruistic glow to scientific and technological research that was hardly humanistic at all. Indeed, MIT was funded by massive defense contracts in the early Cold War period. Much of its advanced research had direct applications in weapons and warfare. The images Kepes featured in his books and exhibitions, the scientists with whom he worked on collaborative ventures and the ideas he borrowed across disciplines were often linked, directly or otherwise, to military power. By the late 1960s, when opposition to the war in Vietnam intensified across college campuses, Kepes faced significant backlash for this very reason.

—Sibyl Moholy-Nagy to Gyorgy Kepes

Perhaps the single most powerful denunciation of Kepes’s programme was a letter written to him by Sibyl Moholy-Nagy, the architectural critic and second wife of Kepes’s former mentor, László Moholy-Nagy. In the letter, Sibyl Moholy-Nagy excoriates Kepes, seeing him as complacent, as an organisation man embedded in the military-industrial complex: ‘Does it not occur to you that the computer boys of MIT are playing a game of words and figures that could kill every last instinct for sense values if it were to conquer the territories it so naively invades now? … No matter how many new puzzles you publish, Gyuri, they will never make a total picture. … What you need more than anything else is to get out of MIT and Cambridge as fast as you can to save your soul and your talents and your integrity. You have no idea how silly and 19th century deterministic their programmes look from the outside.—There can be no ‘integration’. We can only be saved by drawing new boundaries. … I still hope for your disenchantment with the Bauhaus programme.’[9]

In another letter to Kepes, written on the occasion of the establishment of the Center for Advanced Visual Studies at MIT, she was even more forceful: ‘The staggering guilt of Vietnam lies ultimately with the ideologists of technological progress, the way the ultimate guilt of Hitlerism lay with Nietzsche and the ideologists of the Germanic super race.—Science and technology live by permission of the military establishment. I do hope … that the miracle will occur that reconciles what MIT is doing for the war effort with your vision of creativity.’[10]

Kepes was ultimately unable to escape such criticisms. As the Vietnam War intensified, as antiwar protest accelerated, he inevitably found himself on the wrong side of the military-industrial complex, despite his vocal opposition to the war in Vietnam.

Through visual design, Kepes responded to the ‘two cultures’ dilemma by developing an elaborate and evocative interdisciplinary programme. But visual design did not offer a critical examination of the sciences or their charged entanglements with the arts. It was unable to assess the social, political and ideological fallout of bringing art and science together. Kepes merely hoped to create dialogue, exchange and collaboration—not to offer critique. He was conformist and technocratic in style and non-confrontational in approach—a classic Cold War liberal. Kepes therefore serves both as a model for the potential of interdisciplinarity in design and a warning for the limitations of such an approach.

is Endowed Associate Professor of Contemporary Art in the School of Art at the University of Arkansas, where he is also director of the art history programme. His book Gyorgy Kepes: Undreaming the Bauhaus (MIT Press, 2019) was a New York Times ‘Best art book of 2019’ and was a finalist for the 2020 PROSE Award in Art History & Criticism conferred by the Association of American Publishers. Blakinger’s research and teaching consider connections between art, science and media technologies, the relationship between aesthetics and politics, and protest and activism in the arts.