A New Deal for the New Designer: New York’s Design Laboratory, 1935–1940

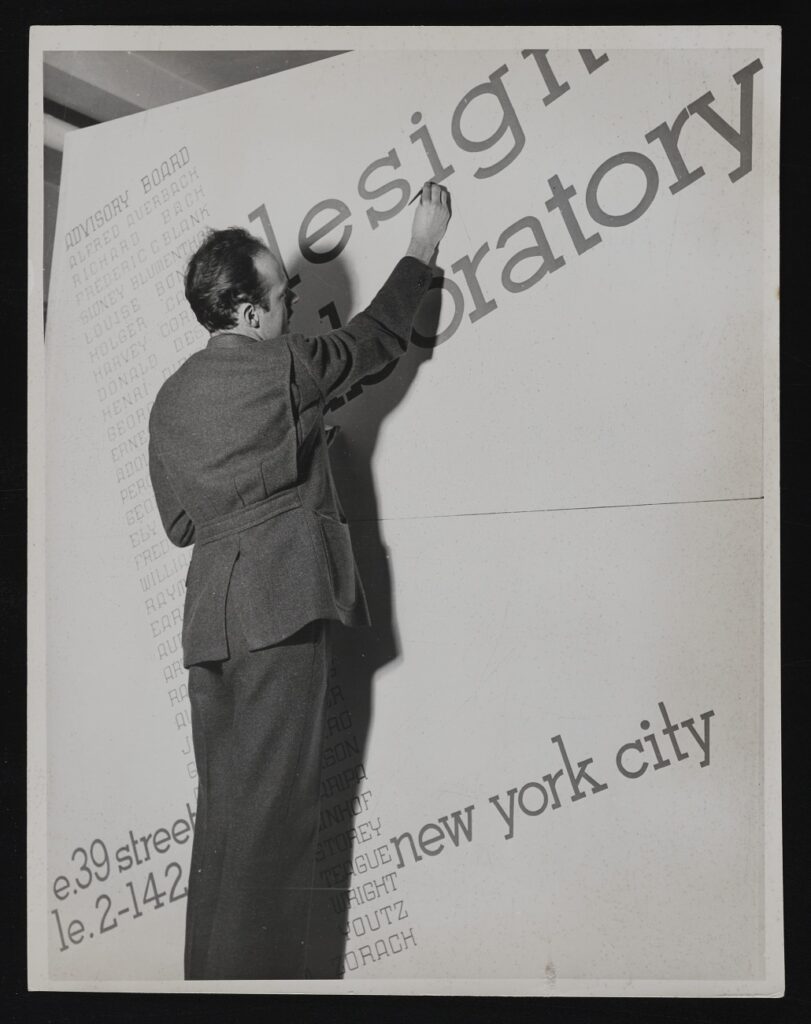

In the United States, the Bauhaus ideal of the New Designer first took root in the midst of the Great Depression, as the administration of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt responded to the protracted economic crisis with its New Deal program that included public employment initiatives, major infrastructure investments, and a basic system of social insurance. As part of the New Deal, in 1935 the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project (FAP) launched the Design Laboratory in New York City as the first comprehensive school of modernist design in the United States that was open to general enrollment.

Like the Bauhaus pioneers, the Design Laboratory faculty saw their mission as not just the development of a pedagogy and curriculum to train designers with technical proficiency in modern aesthetic trends, materials, and manufacturing methods, but rather to train designers who identified as agents of social transformation and reconstruction.

Within the American context of the 1930s, their quest to create the New Designer was enmeshed within the broader struggles over the aspirations and limitations of New Deal social democracy. For its five years of operation, the Design Laboratory furnished a vibrant nexus between a novel public arts bureaucracy, the experimental modernism of the Depression-era avant-garde, the business culture of America’s industrial design entrepreneurs, the militant labor unionism of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), and the political radicalism of the Popular Front social movement.

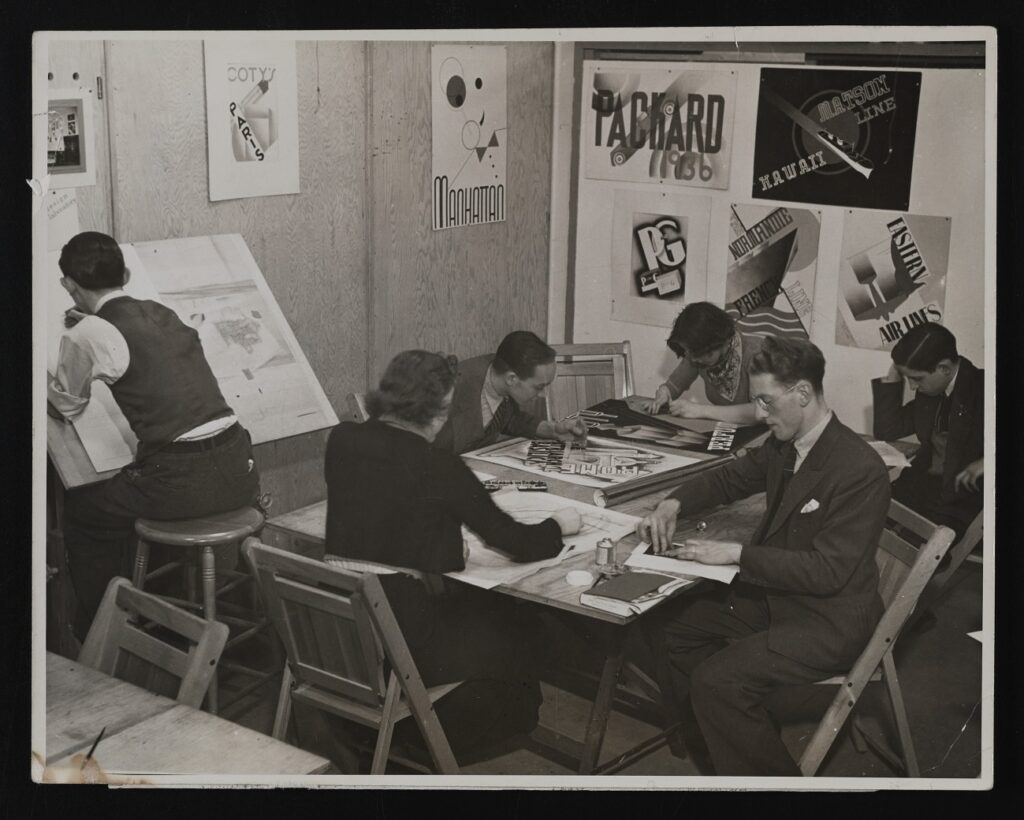

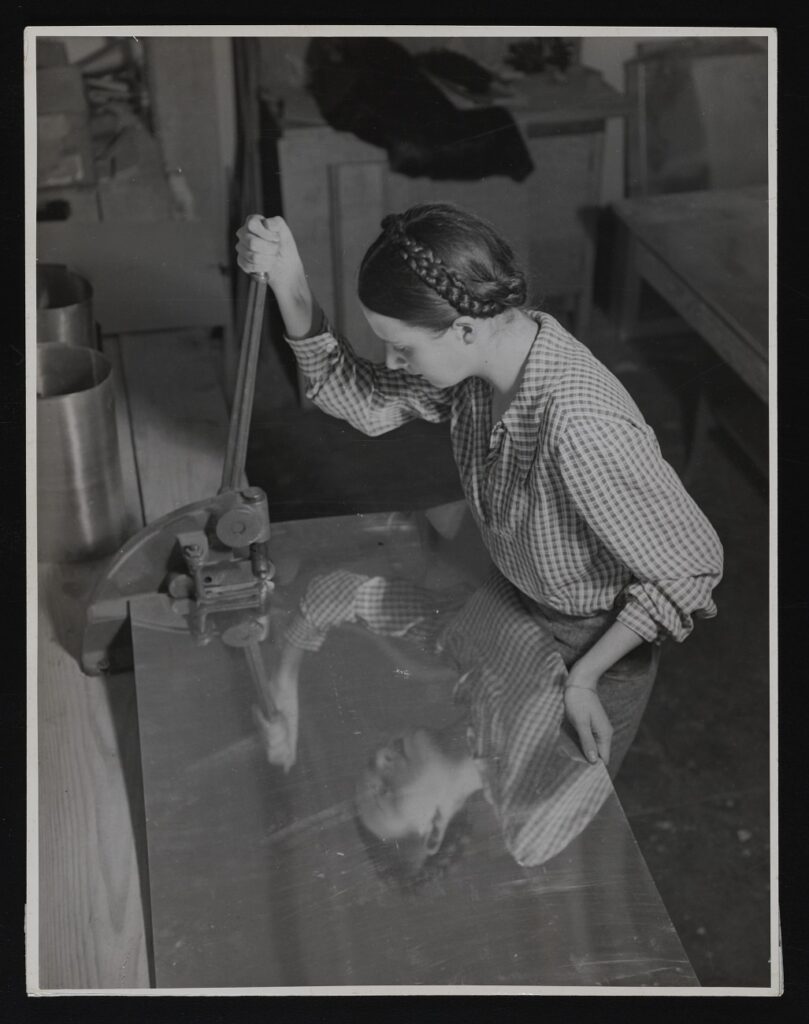

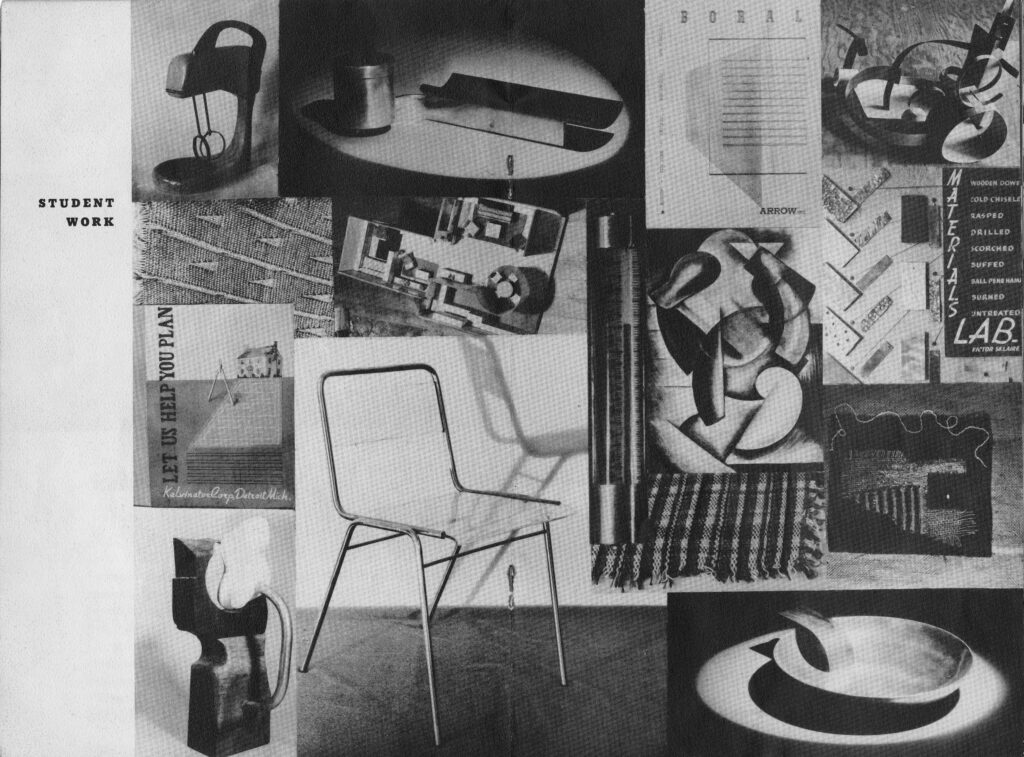

From the outset, the Design Laboratory’s faculty, which included Bauhaus alumnae Hilde Reiss and Lila Ulrich, improvised in both their approach to design education and in their ongoing struggles to establish the school as a viable institution. In their focus on experimentation, they drew inspiration from the pragmatist pedagogy of John Dewey, whose educational innovations had also influenced the development of Bauhaus methods. Early coursework emphasized familiarity with a wide range of media and techniques, integrating multiple design skills in order to meet the needs of industry.

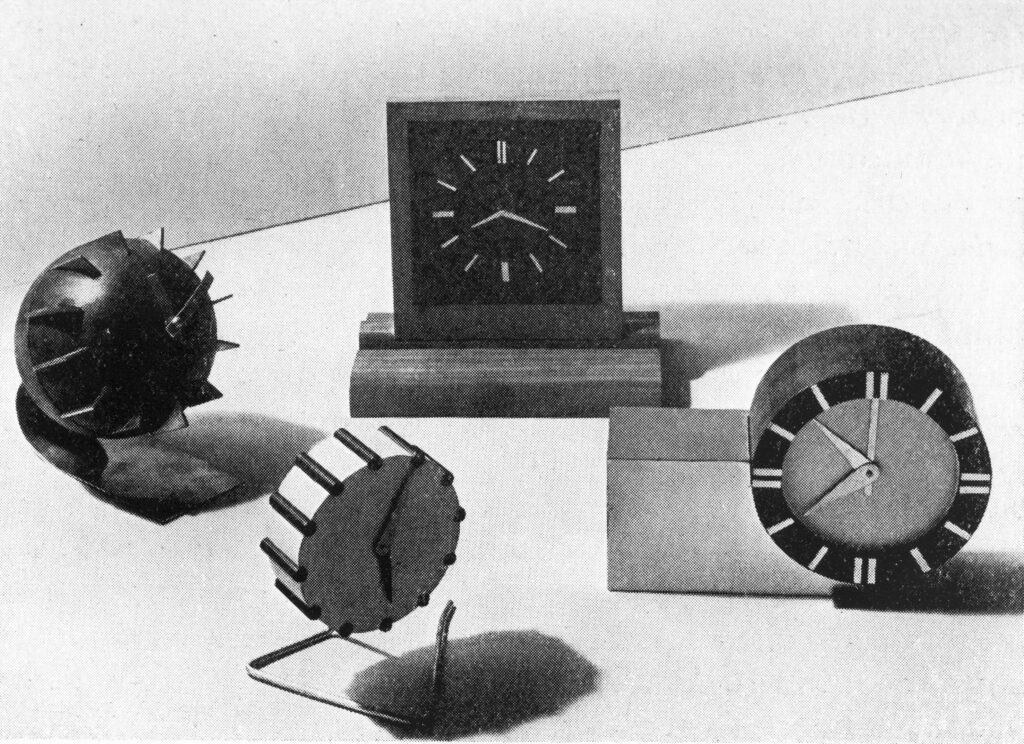

In place of the “existing artificial distinction between interior decoration and the designing of mechanical objects,” according to one of the school’s initial bulletins, classes were “grouped according to present day trends in fabrication and design. In this manner, wood, metal and plastics are treated as a unit.” As its first year drew to a close, it could still claim in a subsequent bulletin that the school was still the only one in the United States to “present in a coordinated fashion the standards of taste and style evolved elsewhere in the world in the so-called ‘International Style,’” even though its intention was not “to hand down dogmas about functionalism and modern design.”

While the Design Laboratory owed its existence to the FAP, faculty and students soon found that their vision for the school’s development was at odds with that of the agency’s administrators. FAP director Holger Cahill and others in the agency hoped that the Laboratory would provide a source of competent personnel for its geographically dispersed programs to democratize American culture, but the school’s faculty and students proved reluctant to leave New York for remote locales in the hinterlands. The status of the FAP as a temporary agency to alleviate the unemployment crisis also led to tension, as it compromised efforts to develop a multiyear curriculum for the Laboratory that would culminate in an academic degree, and it limited the school to hiring mostly individuals who met eligibility requirements for “relief” employment.

By late 1936, faculty and students were organizing to establish the FAP on a permanent basis, and participating in militant demonstrations –including strikes and occupations– to try to win pay increases for public workers and prevent job losses. When the federal government curtailed funding for all New Deal programs, including the FAP, in mid-1937, the agency’s administrators designated the school as one of the programs to be eliminated.

Determined to see the Design Laboratory continue, a group of teachers and students, led by faculty chairman William Friedman, arranged for the Federation of Architects, Engineers, Chemists, and Technicians (FAECT), a radical, white-collar labor union affiliated with the newly formed CIO, to sponsor the school. Operation under union auspices was liberating in some key respects. In the fall of 1937, the faculty implemented a complete four-year curriculum that featured an introductory materials laboratory modeled on the Bauhaus preliminary course along with a two-semester design synthesis sequence intended to familiarize students with a diverse range of modernist styles and techniques. Faculty and students were also more closely aligned ideologically with the FAECT than with the FAP, and they refined their conception of the New Designer in the context of the radical politics of the Popular Front.

The school’s new declaration of principles asserted that “mass production, being dependent on mass consumption, necessitates designs to meet the social needs of the consumer.” Designers were to place “as little emphasis as possible on ornament,” avoiding “arbitrary” decorative elements that had “no genetic connection to the functional and mechanical properties of an object whose surfaces they adorn superficially.” Art historian and critic Elizabeth McCausland, an ardent supporter of the Design Laboratory who eventually joined its faculty, avowed that “the original Bauhaus, germinal as it was, suffered somewhat from the romantically individualistic self-expression of the men of genius who founded and conducted it.” By contrast, she continued, the Laboratory’s faculty and students understood that “the most beautiful architecture, design, and art is not built by the individual, but by the coordination of the talents and technics of individuals within the containing envelope of social relations.”

Freedom from FAP requirements also gave the Design Laboratory much greater leeway in expanding the faculty. The core group of instructors from the early days, anchored by Friedman, Reiss, painter Irene Rice Pereira, and product designer Jacques Levy, grew in the late 1930s to include McCausland, graphic design prodigy Paul Rand, muralist Burgoyne Diller, industrial designer Peter Schladermundt, painter László Matulay, and furniture designer Törben Muller among others. Enrollment, which had been robust under the FAP when courses were free, actually increased once the school began charging modest tuition under FAECT sponsorship, peaking at 400 students in late 1937.

Unfortunately, the union’s financial instability forced a second reorganization in 1938, with the school becoming an independent cooperative institution. Formally renamed the Laboratory School of Industrial Design, it received authorization from the New York State Board of Regents to confer Bachelor degrees. Although the faculty continued to enhance and improve the pedagogy and curriculum, the failure of a major fundraising drive in the fall of 1939 ultimately doomed the school, which was forced to suspend operations the following spring and return its charter to the state. Its faculty and students (most notably product designer Don Wallance and interior designer Suzanne Sekey) dispersed throughout America’s culture industries and institutions of higher education, taking their experiences at the Laboratory with them to their future creative work as artists, teachers, and critics during the middle decades of the twentieth century.

As our climate emergency of the early twenty-first century leads to calls for a Green New Deal, the example of the Design Laboratory – and its mission of developing a New Designer capable of responding to complex social crises with a sustainable material culture for social democracy – remains highly relevant today.

holds a doctorate in history and teaches a range of courses on the history of the modern United States. Prior to joining Montclair State in 2008, he taught at Tulane University, the University of Missouri at St. Louis, Columbia University, the Van Arsdale Labor Center of Empire State College (SUNY), and Princeton University. His research explores the development of white-collar work in the twentieth-century United States, with a particular focus on labor relations within the culture industries, including advertising, the print media, the broadcast media, and design. He is the author of The Making of the American Creative Class: New York’s Culture Workers and Twentieth-Century Consumer Capitalism.