Editorial: What might be truly social

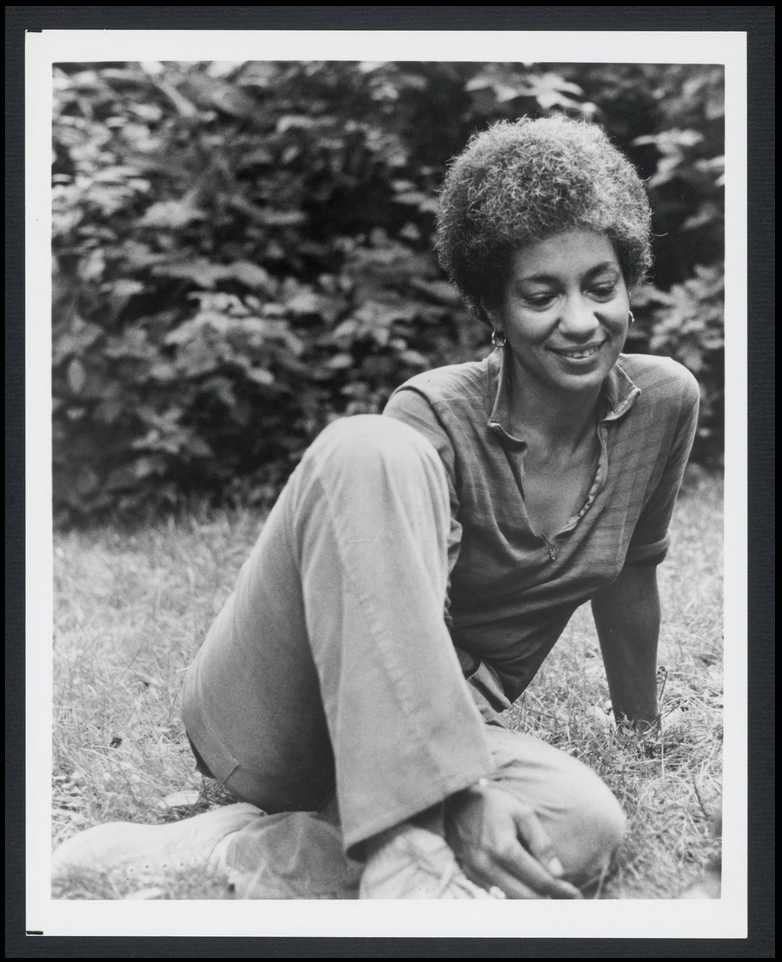

‘So, back in 1964, I resolved not to run on hatred’, writes Black feminist poet, activist, journalist and educator June Jordan, ‘but, instead to use what I loved, words, for the sake of the people I loved. However, beyond my people, I did not know the content of my love: what was I for? Nevertheless, the agony of that moment propelled me into a reaching far and away to R. Buckminster Fuller, to whom I proposed a collaborative architectural redesign of Harlem, as my initial, deliberated movement away from the hateful, the divisive.’[1]

The ‘moment’ Jordan is referring to, the one that prompted her to reach ‘far and away’ to Fuller, is the very one that sparked the Harlem Riot of 1964: when James Powell, an unarmed Black fifteen-year-old boy, was fatally shot by a white police officer on Manhattan’s Upper East Side – only a few days after Lyndon B. Johnson had signed the Civil Rights Act. It was a period Jordan describes as the ‘zenith of her preoccupation’ with the visionary ideas of the maverick architect, designer, philosopher, poet and inventor.

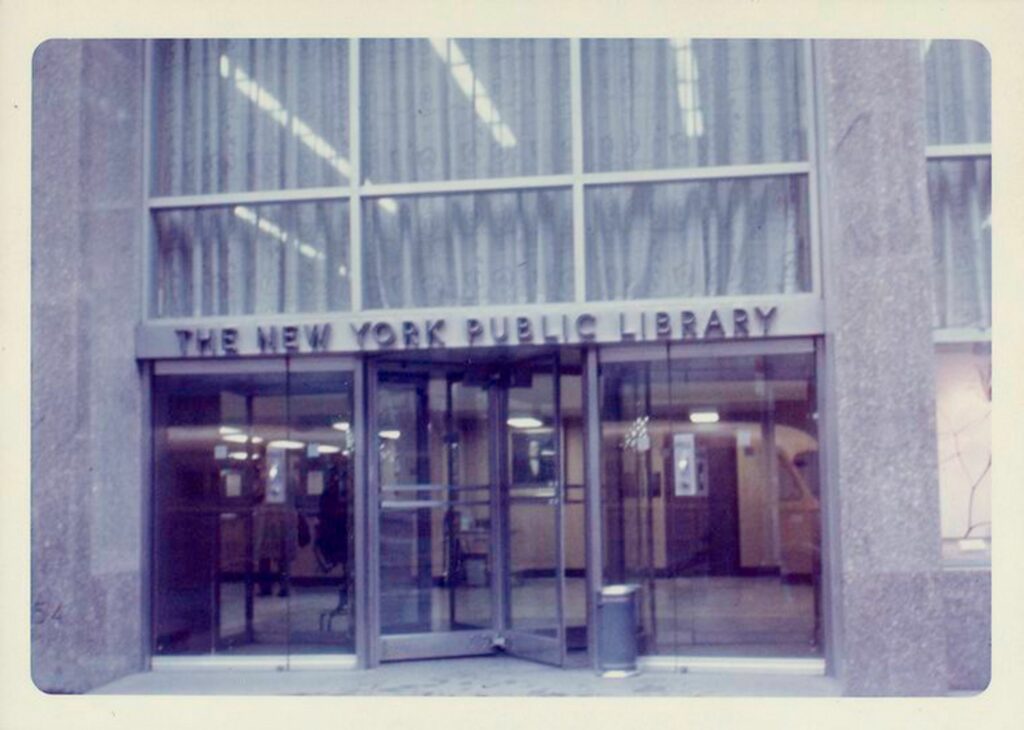

Having long spent stolen free moments at The Donnell Library, poring over books and losing herself in their pages ‘among rooms and doorways and Japanese gardens and Bauhaus chairs and spoons’, Jordan had grown to believe in the transformative possibilities of design. Immersing herself in the principles of Bauhaus practice, she had come to ponder whether a spoon alone might indeed go some way towards countering the ‘endlessly, dysfunctional clutter/material of no morale, of clear, degenerating morass and mire, of slum, of resignation’ affecting people living in poverty.[2] Yet her conviction that design could launch a social revolution was only truly cemented upon her ‘meeting’ Buckminster Fuller, also at the library: in the photographs she saw of his inventions, in the stories she read about his life and the writings of his she devoured, among them Nine Chains to the Moon (1938) and Education Automation (1962). Fuller’s seldom-realised adventures in thought weighed upon her own ‘as a hunch yet to be gambled on the American landscape where, daily, deathly polarization of peoples according to skin gained in horror as white violence escalated against Black life’.

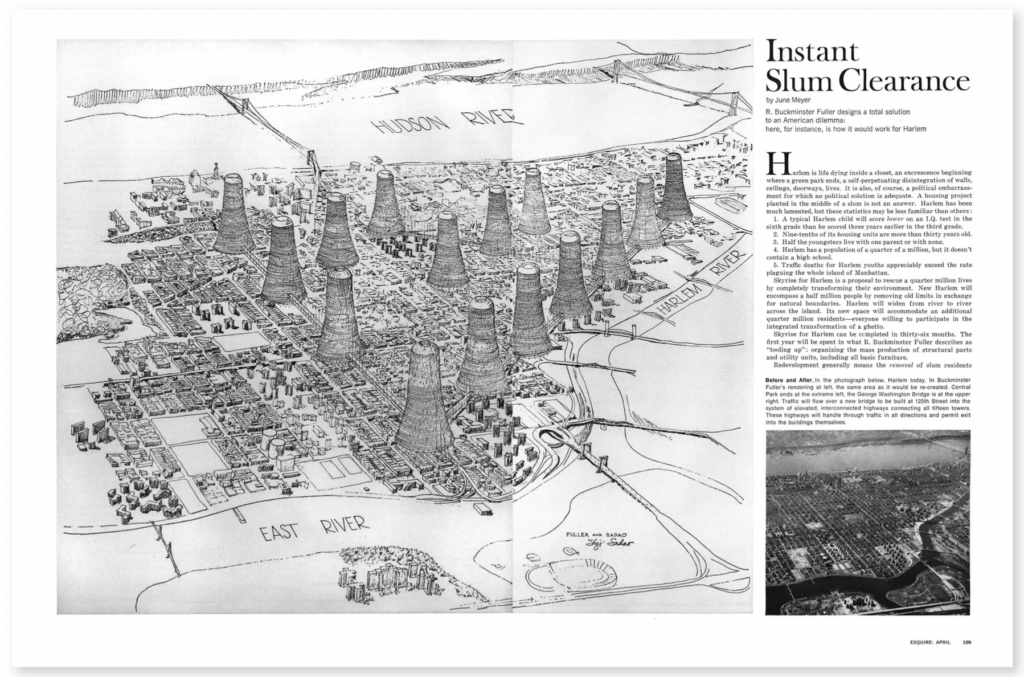

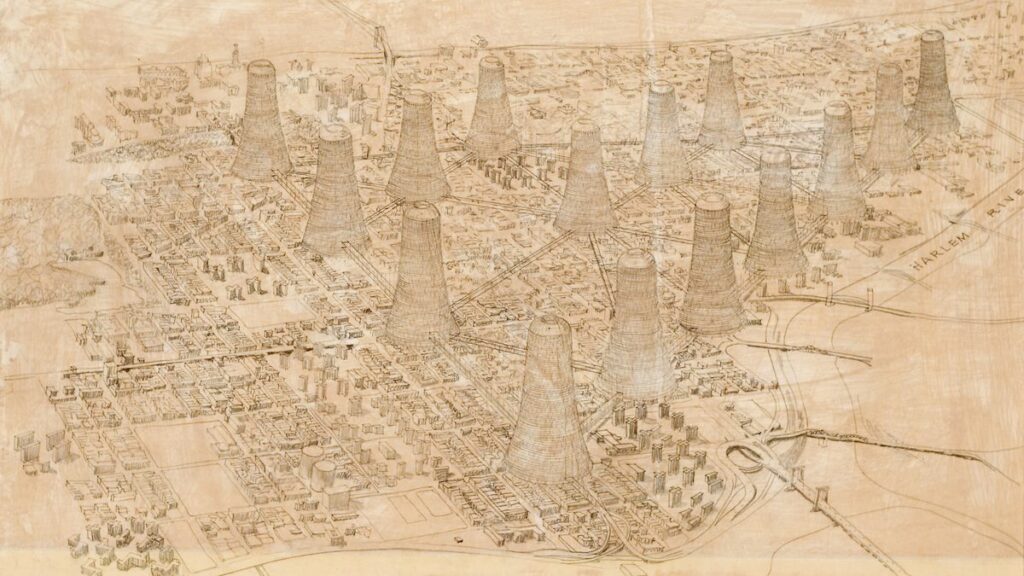

A week after the riot, Jordan wrote a letter to a receptive Fuller, thereby launching a long-term collaboration in eco-social counter-design thinking that culminated in ‘Skyrise for Harlem’: a concrete plan to ‘obliterate the valley of shadows’, to bring an end to the ‘self-perpetuating disintegration of walls, ceilings, doorways, lives’ then home to a quarter of a million people, and to radically exorcise ‘a half century of despair’ in a manner no ‘partial renovation’ or ‘piecemeal healing’ could ever achieve.[3] Rather than making urban renewal contingent upon the expulsion of residents, as was – and still is – common practice, their vision foresaw the construction of new dwellings above the moribund tenement buildings. Residents would remain living there until they could move up to their new home within a conical structure offering views from every window. The process, they anticipated, would take three years. And it would be participatory: Harlem residents would take part in the ‘birth of their new reality’, a reality intended to reassure those who lived there ‘that control of the quality of survival is possible and that every life is valuable’.[4] Upon completion of the elevated towers, the old buildings below would be demolished to make way for parks, open spaces, public seating and safer walkways. ‘No one’, maintains Jordan in her article on the project for Esquire magazine, ‘will move anywhere but up.’

At the time of its publication, Jordan’s article met with widespread scepticism and some measure of derision; its content, though collaboratively developed, was ascribed to Fuller. Yet today the plan is coming to be regarded as a critical milestone in environmental design history, despite its never having come to fruition. For who other than Jordan, asks K. Wayne Yang, ‘has designed possibilities for Black life that keep Black communities intact, Black people emplaced, and Blackness integrated into the landscape? Check out her design, and decide if it looks like Wakanda to you too’.[5]

What’s at once intriguing and instructive about this ‘architextual collaboration’[6] about this poetic experiment in ‘comprehensive design’, this revelatory exercise in design as dissent, as social responsibility, as revolution, are the multifarious insights it offers – and pivotal questions it raises – about the evolution of design as a profession. These insights, these questions might be thought of as a point of departure for the lines of enquiry gathered together within the present journal, The New Designer: Design as a Profession.

The first such insight pertains to the role of the riot, indeed of crises – social, economic, political and ecological – in bringing forth and perpetually remoulding the figure of the new designer, a ‘social type, bearing a humanistic, universal outlook’ and working towards ‘the benefit of humanity as a whole’.[7] There is little consensus on what might be truly ‘social’, on what could be truly beneficial to humanity, or on whether it even makes sense to think in terms of humanity ‘as a whole’. Yet from Anni Albers to Arturo Escobar, few design theorists have felt inclined to dispute the impact of war, civil unrest and climate catastrophe on design pedagogy and practice.

Second, one might recognise that there is as much design to be found and learned from in slums and housing projects, in war and structural racism, as there is in Jordan and Fuller’s ‘Skyrise for Harlem’ or for that matter any other of Fuller’s visions for Spaceship Earth. As Fuller’s colleague and friend Victor Papanek demonstrated in Design for the Real World, design is inextricably bound up with social processes. It can both undermine and augment social justice. Yet more often than not it becomes a tool of technocracy or a catalyst of consumption, as opposed to an agent for social change.[8] For all their poetry and pertinence, benign observations, such as that of Cuban-born Mexican designer Clara Porset, about there being design in everything, ‘in a cloud … in a wall … in a chair … in the sea … in the sand … in a pot’,[9] are of little consequence to thought if we fail to include in the list the iCloud … the Berlin Wall … the electric chair … the plastic ocean … sand erosion … potheads …

Third, one could discern the perceptible tension between competing visions of total design to have formed the new designer, both of them differently lacking in self-reflection on their entanglement with capital and industry. Embodied in Jordan’s intellectual transition from teaspoons to towers, from Bauhaus to Bucky as it were, it is a tension that, on one hand, reflects the successful export of Bauhaus thinking to all corners of the world. As Mark Wigley points out, and various contributions to the present journal discuss, not only were ‘objects designed, mass-produced, and disseminated; the designer himself or herself [was] designed as a product, to be manufactured and distributed. […] Even the teaching within the studios was a product. Gropius said that he only felt free to resign in 1928 because the success of the Bauhaus was finally established through the appointments of its graduates to teaching posts in foreign countries and through the adoption of its curriculum internationally’.[10] Yet on the other hand, the faith Jordan placed in Fuller, with his rambunctious, all-encompassing philosophy of shelter and survival, speaks of a growing preference, shared by many, for his humane, humorous, hopeful brand of experimental interdisciplinarity. For all its overt fallibility, his action plan to ‘make the world work for 100% of humanity, in the shortest possible time, through spontaneous cooperation without ecological offense or disadvantage of anyone’[11] took people’s breath away.

Fourth, one should note the complex dynamics at work in design pedagogies – and in the ways in which these go down in history. Jordan learned about design from studying its products and the ideas that informed them in books held at the library. In a certain sense, she was not that different from Anni Albers and her fellow students at the Bauhaus in Dessau, who contrary to much myth and lore, claimed to have had no ‘education’ as such. They had learned their craft not from listening to the ‘great masters’, Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee, neither of whom ever deigned to speak to students, but from studying their works[12] and predominantly from ‘groping and fumbling, […] experimenting and taking chances’ in a chaotic but stimulating laboratory-like situation.[13] Josef and Anni Albers, and indeed Buckminster Fuller himself, maintained that it was only in the United States, specifically at Black Mountain College that they gradually began to develop formal teaching methods – in constant exchange with their students and fellow professors. The same can be said of many of their Bauhaus-educated colleagues, whether they were teaching at Black Mountain or any of the other reform-oriented educational institutions scattered across the globe.

Though Jordan had never attended any design school, though she had had no formal exposure to modern or contemporary design pedagogies, she was able to bring to bear her self-taught knowledge of modern design in collaboratively redesigning Harlem from the ground up. With her extra-institutional trajectory, she was able to form a team with an esteemed, practising designer, who, as can be gleaned from their extensive correspondence, learned as much from Jordan’s knowledge of sociology and political imagination as she did from his ‘Comprehensive Anticipatory Design Science’.[14]

Until recently, all articles and exhibitions documenting the project attributed it solely to Fuller. Had Jordan, herself, not written of their collaboration in Civil Wars, we may still be waiting for the vital critical reappraisal that would return her silenced voice, her erased agency to a narrative so impoverished without her. This same reappraisal, which has gathered considerable momentum in recent years, confidently establishes Jordan as a ‘new designer’ insofar as ‘she plots buildings and plots freedom’.[15] It is a move that invites us to not only investigate the countless other protagonists and stories missing from the histories of design pedagogy, but also to rigorously rethink, as each of the contributors to this journal have been invited to do, how precisely the figure of the ‘new designer’, this new ‘social type’, has come into being – and to reimagine what she, he or they might embody today.

is an arts and literary scholar, curator and writer based in Berlin. Since completing her doctorate at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia, in 2001 with a thesis on Hans Magnus Enzensberger, she has curated a broad range of cultural history exhibitions at institutions across Germany on topics spanning from the Reformation to the passions, from the sun to sexuality. She has also mounted numerous monographic and thematic art exhibitions including ‘Beuys: We are the Revolution`, ‘The End of the 20th Century: The Best Is Yet to Come’ and ‘Capital: Debt – Territory – Utopia’ for the Nationalgalerie im Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart – Berlin (in collaboration with Eugen Blume) and ‘Everyone is an Artist: Cosmopolitical Exercises with Joseph Beuys’ (in collaboration with Isabelle Malz and Eugen Blume) at K20 Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Düsseldorf. She has published widely on contemporary art as well as editing numerous catalogues and books, such as Bruce Nauman: Ein Lesebuch, Black Mountain: An Interdisciplinary Experiment, 1933–1957 and Shine on Me: Wir und die Sonne. She was the artistic director of beuys 2021, a year-long centenary programme comprising some 30 cultural events in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia as well as an online radio station, a symposium and an interdisciplinary laboratory exploring radical democratic forms of collectivity. She recently curated Manifesta 14 Prishtina – it matters what worlds world worlds: how to tell stories otherwise – and currently works as a curator at the Nationalgalerie im Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart – Berlin.