Never Get Too Comfortable: On Schooling Design

Dear Marina, it was the productive disquiet with which you work on design institutions within design institutions that first caught my attention. It was your restless quest to rethink, to reimagine, to co-think, to co-imagine institutional paradigms and design pedagogies that drew me deeper into your research, that made me want to listen to your presentations and somehow retrace the trajectory of the thought process that has brought you to where you are now: at the forefront of reflection on how design practices and practitioners might rise to the social, economic, political and ecological challenges we face on a planetary scale.

In registering your preoccupation with temporal, itinerant structures and sites of learning, already manifest in your doctoral thesis Evanescent Institutions: Political Implications of an Itinerant Architecture (2016), I was reminded of an idea I stumbled across some years ago in conducting research on Black Mountain College as an exemplar of ideal or alternative universities. John Andrew Rice, the college’s founding rector, argued that colleges should be in tents. Rice was convinced that any idea, no matter how humane, no matter how progressively-minded, would sink into the institution within ten years, at which point the college could – and should – fold up like a tent and move on, regroup, think again. Looking at the history of design education, do you think there’s something to be said for Rice’s tent theory? Might the ‘tent’, whether physical or metaphorical, be considered a prerequisite for innovation in design education?

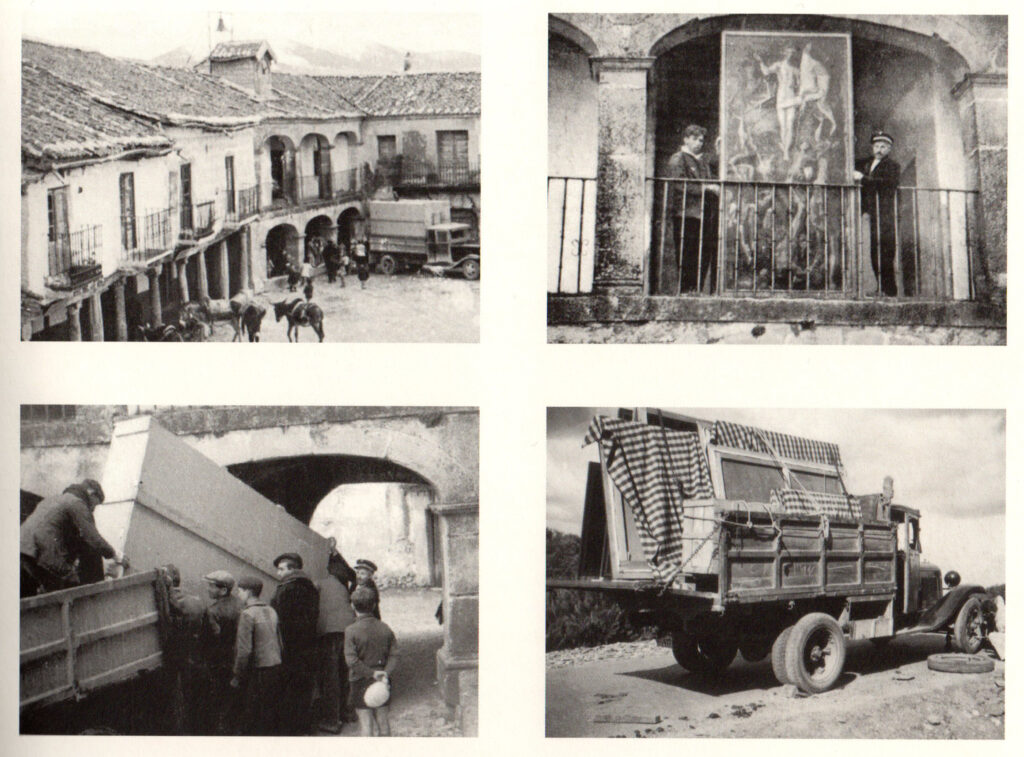

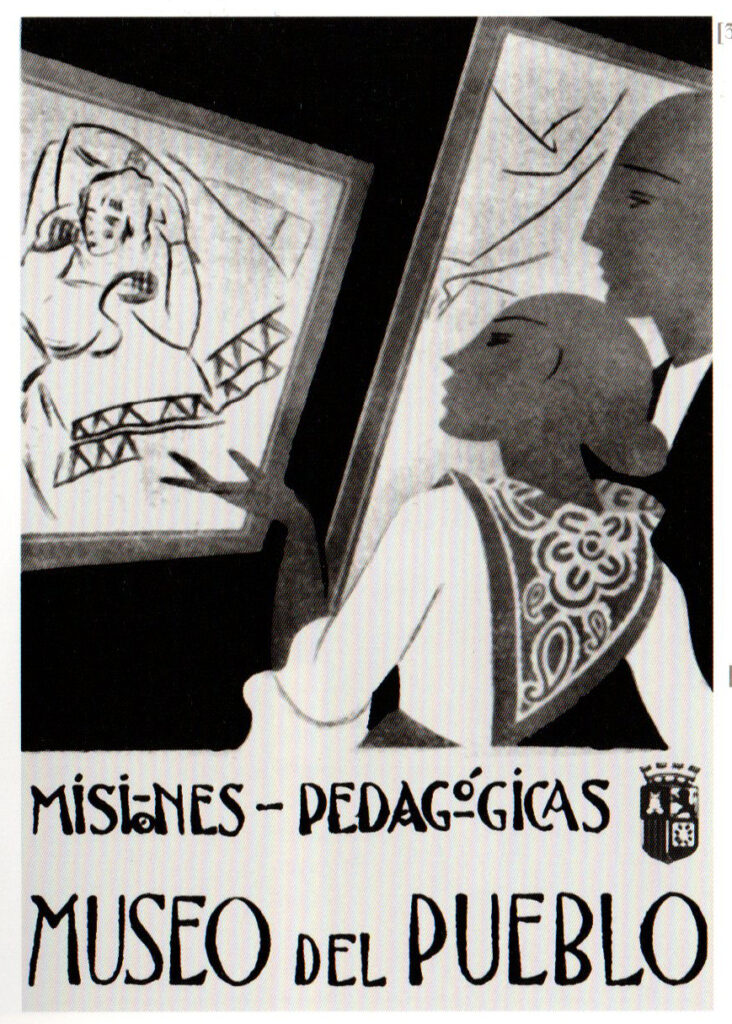

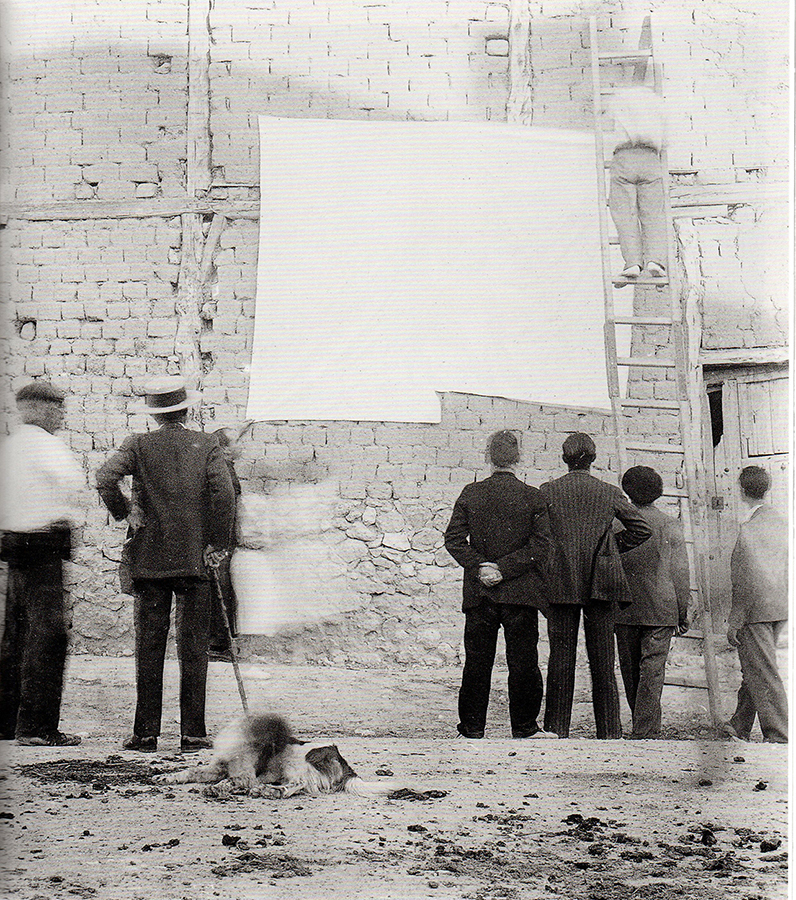

Thank you, Catherine, for your generous words and for taking the time to learn more about the work I do. Responding to your question: absolutely. It reminds me of a few projects that sparked my imagination for decades, that were case studies in my Ph.D. thesis and always present during my attempts to study and test alternative institutional formations: Misiones Pedagógicas (Spain, 1931–1936) and Laboratorio di Quartiere – Urban Travelling Reconstruction Workshop by Renzo Piano (Otranto, Italy, 1979). Whereas ephemerality is usually associated with instability, temporal projects (such as the aforementioned examples) could harvest enduring energy and transformations. Institutions and the people making them should not get too comfortable, to the point that processes, methods, and aims are taken for granted. To remain relevant to society, institutions must be persistently reinvented and challenged from within – reflecting on and questioning their own practices, biases, structures, and the networks in which they operate. This strategy allows them to resist the temptation of relying only on known paths and validated trajectories.

To allow for emergent models, institutions must learn to channel disruptive powers of imagination. That means that sometimes they have to find a way to do the groundwork and evolve or, as Rice proposes, to fold up, move on, regroup, and think again. It is critical to recognise when an institution and those who represent it are driven by inertia, have become too entrenched in power, and are more concerned with its reputation and continuation than its relevance.

After more than seven years, I left my position at Het Nieuwe Instituut (HNI) to avoid becoming part of that type of institution. I had to redirect my commitment towards something more relevant than any single institution or myself and my career. It was not an easy decision or process. My main focus now is to make friends, comrades, and allies and to put together ‘tents’ for knowledge exchange, forms of solidarity, empathy, and appropriate redistribution strategies while enjoying the time together. I am full of enthusiasm.

What about economic and political upheaval? Would you say that they were equally important motors for pedagogical innovation?

Innovative approaches have emerged out of necessity and amid the turmoil of a global pandemic, recession, rising inequality, and protests over racial injustice. Institutions, faced with societal demands against patriarchal and racial oppression and for more horizontal structures and power/knowledge relations, have embraced different strategies. At the core of the struggle is the future of living together. These actions and efforts held up a mirror to existing cultural institutions and those like me who worked in them. Some responded to the calls for their transformation and have carried out incomplete, contested, and, at times, failed yet relevant attempts at alternative forms of organisation and action. Others made cosmetic changes and focused on promoting the illusion of stability.

In my work, I have analysed these processes and made comparative studies with events that unfolded ten years ago. Then, unemployment, evictions, and foreclosures resulted from the global economic recession that marked 2011, paving the way for growing global unrest that manifested in anti-government and anti-austerity protests calling for a ‘real democracy’. At that moment, major museums and educational institutions launched initiatives that captured that democratic movement and the interest in turning cultural institutions into sociopolitical agencies (by relocating cultural practices from the interior of institutions to urban public spaces). Examples include the Centre Pompidou Mobile, the BMW Guggenheim Lab or Studio-X.

Many institutions used temporal and mobile models to test new models and channel efforts to mitigate the institutionalised violence embedded in their existing structures. My research revealed that as high walls of cultural institutions seemed to be dismantled, other borders emerged, perpetuating inclusion and exclusion conditions. Despite the innovations and significant transformations triggered by these and other institutions, they also turned into mechanisms of social order and part of urban gentrification processes. Once carrying a subversive potential, the temporary structures were aligned with neoliberal dynamics and were ultimately affected (and put to an end) by the volatility of the markets they served.

These episodes reflected critically on my experience of studying and testing alternative formations – decentralised models for universities, itinerant museums, and more-than-human cooperatives.

Looking at the way you and your colleagues developed the research programme at Het Nieuwe Instituut, the Netherlands’ national museum for architecture, design and digital culture founded in 2013, I found the dedication to developing regenerative strategies within one and the same institution striking and inspiring. I guess you could think of it as an ongoing pitching and dismantling of tents. Neuhaus, a temporary academy seeking to reactivate the founding spirit of Bauhaus 100 years on, might be thought of as one such tent. Could you please tell us a little bit about the objectives of this reactivation in 2019? Which aspects of the Bauhaus pedagogy did you pick up, which did you reject and how did you and your many collaborators go about exploring, critiquing, expanding and transforming the concepts adopted by exponents of the Bauhaus?

You put it beautifully. The ethos of the research team I directed at HNI was never to get too comfortable with our practices, methods, or ideas. We were interested in durational collective research processes instead of quick and stand-alone projects because they allowed us to establish and commit to meaningful alliances during the research. Long, open-ended processes also challenged some of our initial hypotheses and positions. And we discussed that in public, making ourselves vulnerable by showing the process of learning and unlearning, steps and missteps, accepting the possibility of oversights, and making them available for public scrutiny. This open nature didn’t prevent the materialisation of ideas in concrete projects. Yet our projects were never fully finished, not even when they materialised in exhibitions or books. We would not wait until we figured everything out to open for public debate. Instead, our processes emphasised the commitment to sharing ideas and instigating public discussion in the face of the forms of value creation and knowledge fencing that have permeated educational and cultural institutions.

The same applies to the body of the institution and its workings. For us, the institution should host within it its possible alternative futures. In 2020, we even launched an open call titled ‘Regeneration: Open Call for New Institutions’. We imagined HNI as a testing ground for generative endeavours to test and rehearse new notions of the institution and ‘instituting’. Proto institutions that served as blueprints and route maps to interrogate the relevance of today’s cultural infrastructures, starting from HNI, will eventually render them obsolete. It was a process of ongoing institutional ruination and emergence. It kept us busy!

Neuhaus was part of this trajectory, the idea of temporarily transforming the institution into something else, in this case, an academy for other knowledges. But I would argue that the project’s idea came more from a sense of opportunism and a marketing strategy – to celebrate the anniversary of the Bauhaus and align HNI’s program with the international conversation that occurred around this anniversary – and that limited its full potential. In the end, the history of the Bauhaus mainly became a trigger for something else. Even if opportunist, it unleashed dynamic and generative systems. It allowed the channelling of ideas, methods, and tactics from generation to generation to assess their societal relevance.

For me as an onlooker, one of the most captivating updates to the objectives set out by Walter Gropius in his 1919 manifesto was the shift towards a more-than-human subjectivity …

The relationships between human and nonhuman bodies, as well as their classification, have long been a site of inquiry for disciplines such as philosophy, geography, animal studies and radical social sciences. Whereas human/nonhuman ethics are at the centre of contemporary conversations on issues of inequality and the climate emergency, the discipline of architecture has been only timidly thinking beyond the centrality of the human subject. Architectural practices have primarily developed around normative constructions of the ‘human’ (and in particular the notion of ‘man’ as a universal, rational subject), and yet, they are entangled in non-anthropocentric struggles. They have a role in how encounters between beings are structured in time and space, but are generally orchestrated to serve the comfort and privilege of some humans.

The shift towards a more-than-human perspective allows the discipline to venture beyond its Cartesian postulates, prompting its critical reinvention. It unleashes other forms of relationality beyond the compartmentalisation and instrumentalisation of relations and exploitative and extractivist dynamics. It is fundamental for dismantling the boundaries for compassion and the borders that currently define, protect and exploit the common world. More-than-human thinking, I’d argue, dismisses the architecture centred around the white humanist masculinist subject who sees the world as his own possession.

So, the idea of zoöps came about prior to the foundation of Neuhaus? Where has this line of questioning taken the institution – and you?

The zoöps are one type of the testing grounds that we imagined would start as “just an experiment or a pilot project”. The word zoöps is a combination of the Dutch word for ‘cooperation’ and ‘zoë’, Greek for ‘life’. We used this jargon as a Trojan horse to allow disruption inside the institution under the lens of a temporary project. Still, our aim was that these initiatives could eventually transform or even take over the entire institution. These alternative institutions, we imagined, were operating platforms from which to put spatial, material, socioecological, and conceptual models in motion, leading to paradigm shifts.

Influenced by the contemporary milieu characterised by the climate catastrophe, struggles for racial justice, and rising inequality (struggles institutions have often failed to support meaningfully), some of us questioned our positionality. Is it possible to practice alternative, better-suited institutions by working with and from the ruins of the existing and previous ones? Could existing structures be reshaped as non-exploitative spaces for the public good? What if these testing grounds are our main focus and not a disruptive force inside an existing institution? What if we thoroughly practice these alternative institutional formations, forms of gathering and engaging, without having to simultaneously be representatives of the very structures we aim to challenge? I realised, as did some of my colleagues and peers, that we had to continue the work outside the institution.

I noticed that you have looked not only towards more-than-human subjects as sources of regenerative processes and practices in design learning but also to many different institutional paradigms. Which do you think have the most potential for imagining alternative futures?

I have always tried to experiment with methodologies and forms of institutional practice to foster reciprocal relations between the public initiatives of an institution and its institutional culture. I wasn’t always successful. Most of the time, I found myself in paradoxical positions, from which I nevertheless learned.

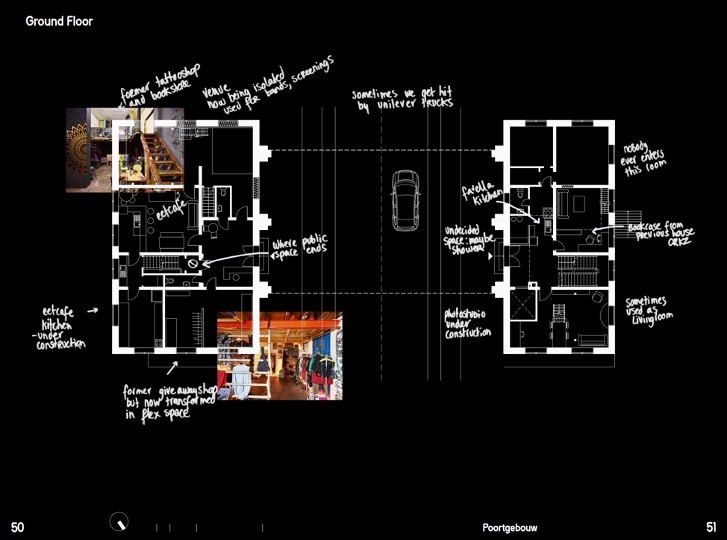

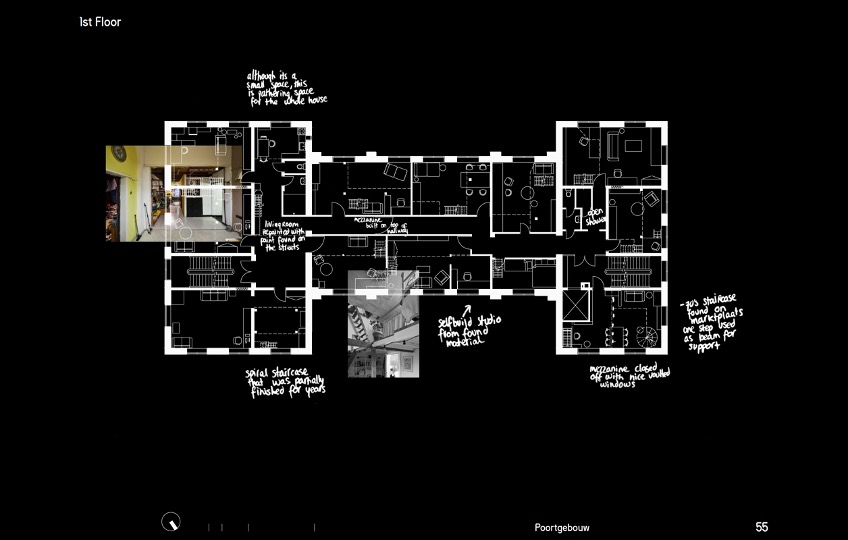

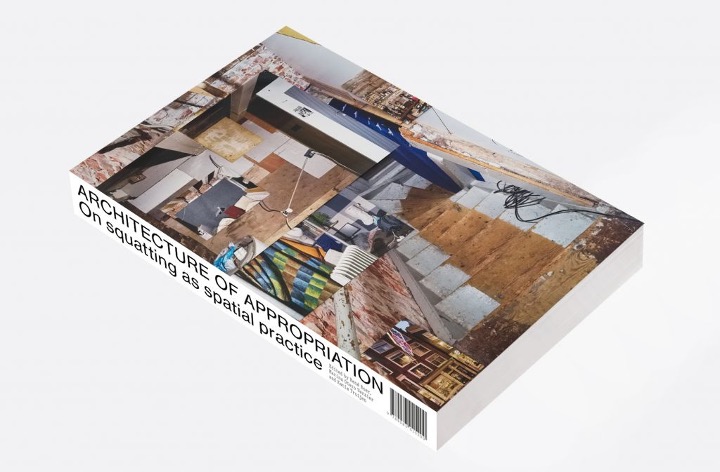

Still, I think some projects, such as those of the Oslo Architecture Triennale 2016 ‘After Belonging’ (notably ‘The Academy’ and the ‘New World Embassy: Rojava’) and HNI’s archival intervention ‘Architecture of Appropriation’ were able to unleash significant transformations. At the Royal College of Art, together with Kamil Dalkir and Ippolito Pestellini, we run the studio ‘Data Matter: Digital Networks, Data Centres & Posthuman Institutions’, which looked at the architecture of data centres as the testing ground for alternative models of post-human institutions. I continue reimagining these digital infrastructures and institutions with the support of Harvard’s Wheelwright Prize.

With the zoöp and similar initiatives such as ‘Burn Out’ and ‘Lithium: States of Extraction’, we tried to put in motion an environmentally conscious practice that could bring ecological thinking into everyday life. In so doing, we also wanted to acknowledge the intimate relationship between the current production and labour systems and burnout processes, with ongoing environmental exploitation and extraction. This is something I continue pursuing as head of the MA in Social Design at the Design Academy Eindhoven. There, we mobilise (not without struggle) design capacity toward post-patriarchal, post-anthropocentric, ecological and plural forms of conviviality. We borrow from epistemologies of the South practices such as Disoñar (a neologism that merges ‘design’ with ‘dream’ coined by cultural activist and designer León Octavio Osorno in the mid-1980s and now used by several groups of peasant activists and intellectuals in Latin America to describe the actions of people who take responsibility for designing their dreams and executing them), or Buen Vivir (a decolonial stance that, according to leading proponent Eduardo Gudynas, calls for new ethics that balance quality of life and the democratisation of the state).

These projects have sparked imaginations, and that is highly necessary. While other paradigms for facing ecological and social challenges are urgently needed, too many of us have lost our ability to imagine alternative worlds under current conditions. Today’s tragedy is humanity’s incapacity to imagine alternative futures. We are subjected to an appalling sense of exhaustion and finitude. Therefore, the exercise of the imagination is necessary to counter the various effects of defuturing (a term coined by design theorist Tony Fry) and the slow cancellation of the future (as argued by author Mark Fisher) of capitalist patriarchal modernity and its structured unsustainability. These defuturing processes, epitomised in modes of living, labouring, producing, and consuming, have created a world that eliminates possible futures for humans and non-humans.

Recognising these tendencies, I decided to change gears before I fell into inertia. I am soon moving back to my country, Spain, and hope to organise a new ‘tent’ in the Galician mountains. The history of the place is intertwined with the regional legends, local ecosocial and feminist traditions of witchcraft, and spiritual practices associated with El Camino de Santiago, which has attracted millions of pilgrims for centuries. From there, I hope to embrace other ways of living, learning, working, and caring. These might be incipient and clumsy, but they are also no longer postponable.

is head of the Social Design master program at the Design Academy Eindhoven. The program focuses on design practices attuned to ecological and social challenges. In 2022, she received the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s Wheelwright Prize for a project on the future of data storage. From 2015 to 2022, she was the Director of Research at Het Nieuwe Instituut where she led initiatives focused on labour, extraction, and mental health from an architectural and post-anthropocentric perspective, including ’Automated Landscapes’ and ’BURN-OUT’. Previously, she was Director of Global Network Programming at Studio-X, Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, New York. Otero was co-curator of the Shanghai Biennial 2021, curator of the Dutch Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2018, and chief curator of the 2016 Oslo Architecture Triennale. She has co-edited the publications Lithium: States of Exhaustion (2021), A Matter of Data (2021), More-than-Human (2020), Architecture of Appropriation (2019), Work, Body, Leisure (2018) and After Belonging (2016), among others. Her PhD thesis Evanescent Institutions (2016) examines the emergence of new paradigms for institutions and, in particular, the political implications of temporal and itinerant structures.