Talk to me! The Design Lab at the Kunstgewerbemuseum Berlin

The many museums of arts and crafts which were founded in Europe and North America in the late-nineteenth century built on a vision of gigantic scope – nothing less than to guarantee product quality and educate the tastes of consumers. Most of the museums of arts and crafts also drew on an equally innovative concept: to build exemplary collections and to educate. This meant that museums and school were frequently found under one roof and thus merged as alternative places of learning. Museums of arts and crafts were far ahead of their time and, coincidentally, firmly rooted in the reality of daily life in the industrial age.

At the turn of the century, educating people’s taste held a lot of practical potential, which was at the same time closely linked with economic interests. Proceeding from the existential question ‘How do we want to, or should we, live?’, the great art nouveau reform project launched with no lesser ambition than to reform society through design, thus establishing a direct and critical connection between industrial production and private life.

The design pedagogics of the 20th century reflect the evolution of society in an industrial nation that had subscribed to an unconditional belief in progress through technology, science and plannability, bolstered by ideas ranging from Walter Gropius’s credo ‘Art and technology. A new unity’ to the maxim of the Ulm School of Design, ‘Design is measurable’. While design increasingly became a recognised and effective tool for the production of social reality and the social dimensions of design came into focus, from as early as the 1960s, the discipline of design per se came under intensifying criticism. Even in 2011, Lucy Kimbell asked, ‘Design leads us where exactly?’ If design should fulfil an important social function, posited Kimbell, then which knowledge do design students need?[1]

And the museums of arts and crafts? Where do they stand in the conflict situation roughly outlined above? In a nutshell, just a few decades after their stimulating foundation, they had passed the pinnacle of their powers. Not only did the schools of arts and crafts dissolve the institutional links with the museums, but the word ‘arts’ in the name also came to dominate. With this, the museums of arts and crafts changed direction. The industrial arts, and along with that everything this term implies in terms of theory and practice, were gradually pushed into the background. With art nouveau, which was celebrated with such pomp at the 1900 Paris Exposition, the majority of museums collected contemporary work for the last time in many years. Thereafter, contemporary design was primarily showcased in the new housing exhibitions or in other special exhibitions. In fact, up to the 1980s it was predominantly applied art that found its way into the schools of arts and crafts, in Germany at least.[2] So-called product design is a relatively recent collection area and only made it onto the agenda of desirable objects some 40 years ago.

Meanwhile, numerous arts and crafts museums have set out on a path of fundamental change to refocus their agenda, in many cases returning to their founding impulse, now again highly relevant. This makes them attractive once again as alternative places of learning for students of all design disciplines and for artisans, who by the same token are rediscovering the potential of these museums.

To support this osmotic revitalisation process, in 2019 the Design Lab series was initiated at the Kunstgewerbemuseum (Museum of Decorative Arts) of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. Conceived as a process-led project, the Design Lab was actualised in various formats ranging from an online research festival[3] and workshops[4] to an analogue exhibition and a digital reader. It utilised the multi-dimensional collections, which extend from the Middle Ages into the present day, as an archive and combined the historical perspectives of this knowledge storage system with forward-looking design research. In our digital world, in which the haptic and material dimension increasingly escape us, the ‘arts and crafts’ collections in particular can act as catalysts for questions about the complex topic of design in the light of the imminent transformation of our living environments.

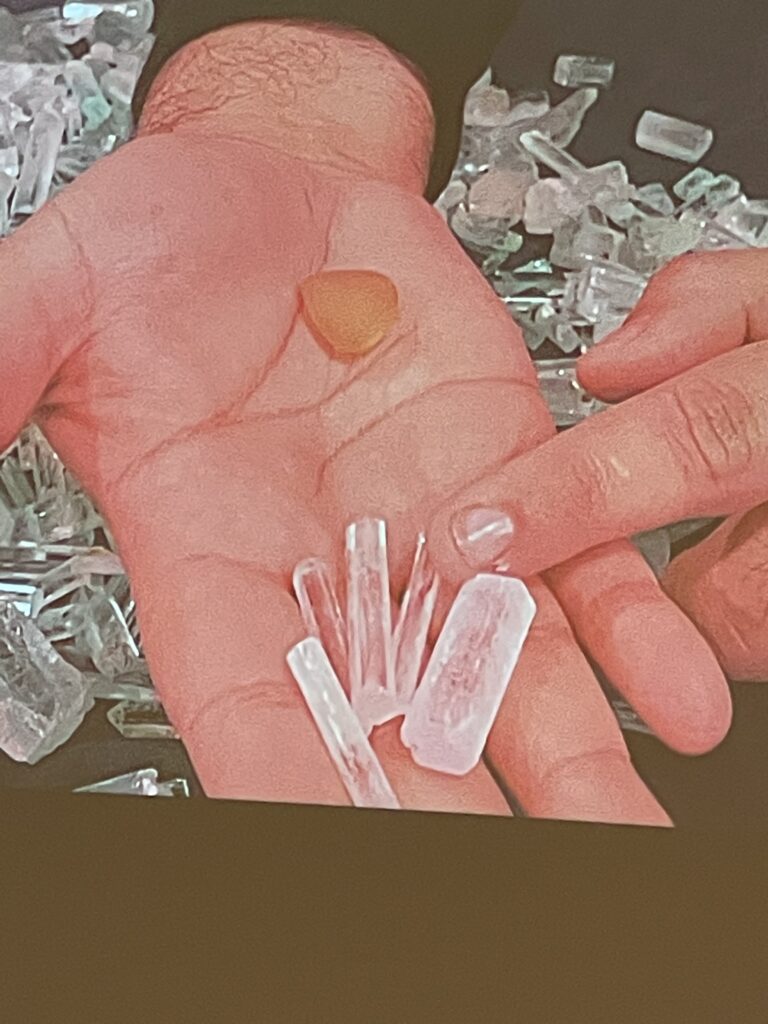

In the discourse on sustainability, materials play a critical role. Materials structure our society in political, economic, environmental, social and cultural terms. Materials form resources that wars were, and are, being fought over. Materials have been, and still are, root causes of colonisations. The geo- and biopolitical dynamics surrounding materials have highly critical effects on the environment, the climate and the social structures of local populations.

Museums of arts and crafts are also intrinsically archives of materials. From the aim of establishing an exemplary collection for all crafts practitioners and future designers evolved a systematisation of objects, adopted from the natural sciences, according to genre, geographical origin and materiality. The main material groups included, first and foremost, textiles, metals, ceramics, glass and wood. The so-called modern materials, most notably plastics, were added to these.

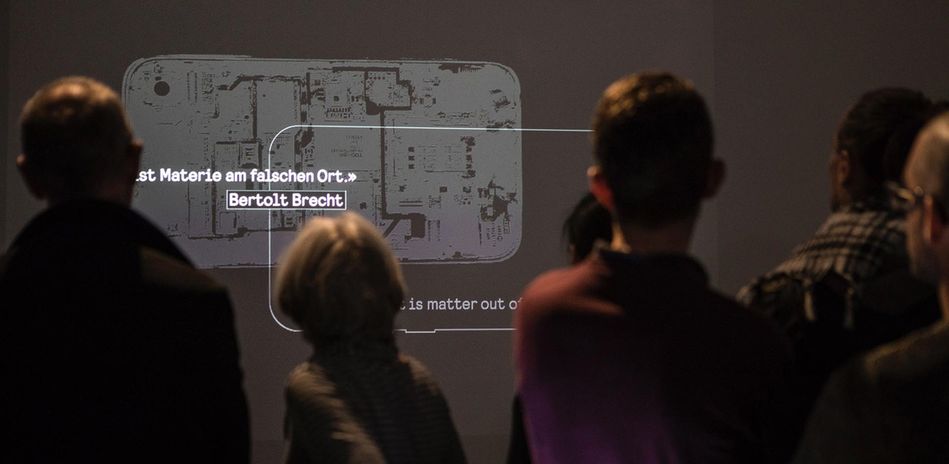

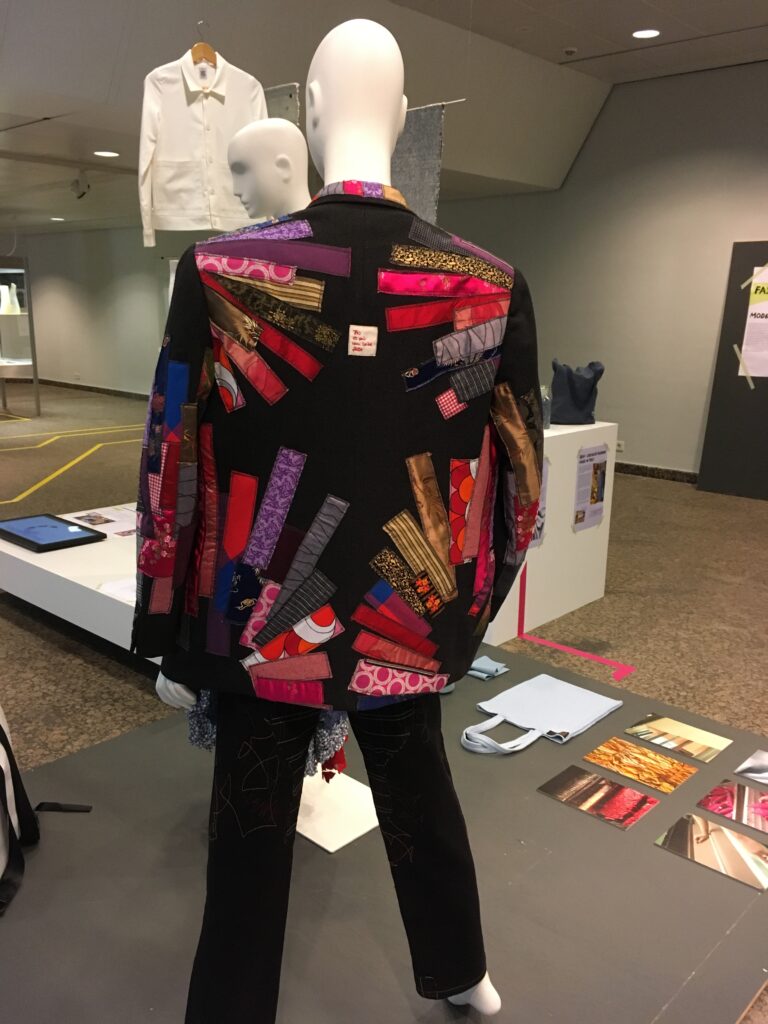

Material was therefore a focal point of several Design Lab projects. Design Lab #5 ’Times of Waste. The Leftover’ focused on the transformation processes of a smartphone and investigated one of the world’s most important technologies, which leaves behind many forms of waste, starting with the extraction of the raw materials it contains.[5] Design Lab #11 ‘LithoMania’ focused on the positive and negative aspects of gemstones.[6] Design Lab #13 ‘Material Legacies’ explored the unsustainable pasts and present of materials and conceptualised possible material future scenarios, focusing specifically on shape-shifting surfaces and phase-shifting textiles.[7]

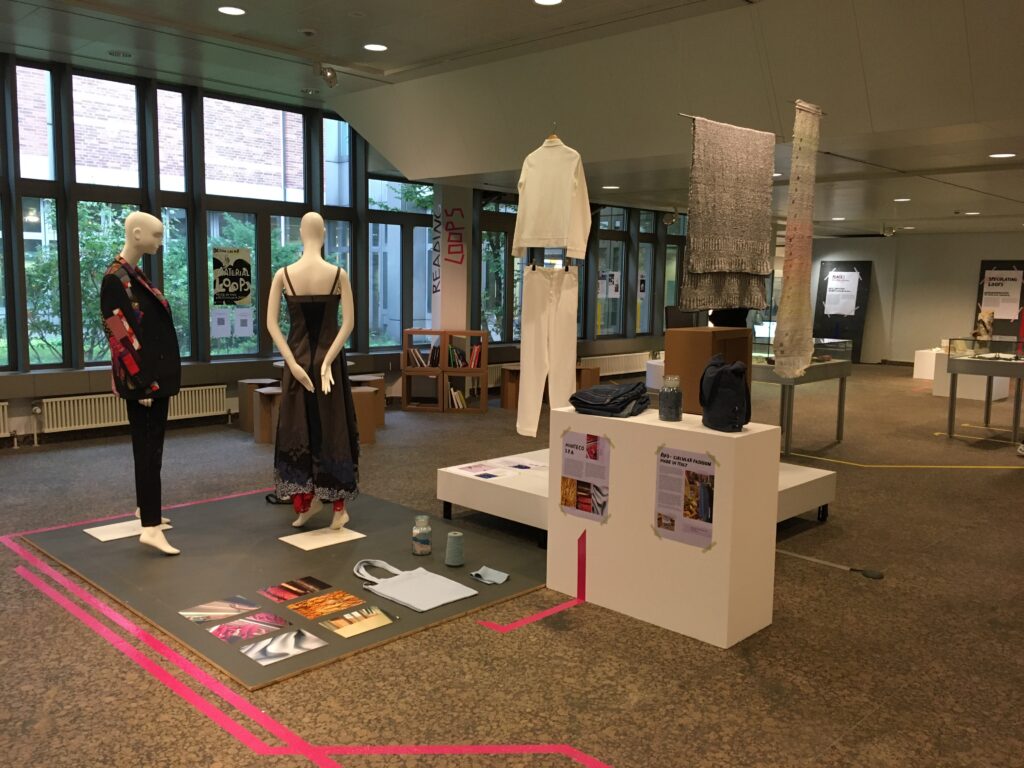

With the term ‘capitalocene’, researchers endeavour to redefine the current age in which our capitalistic forms of production and consumption radically affect all aspects of our geological, biological and atmospheric environment. One of the most important strategies to slow down these negative developments is circularity. Design Lab #8 ‘Material Loops. Paths to a Circular Future’ presented a selection of forward-looking design projects ranging from best practice examples from industry to speculative experiments from design schools.[8] Places in Berlin engaging in circular practices were also introduced.

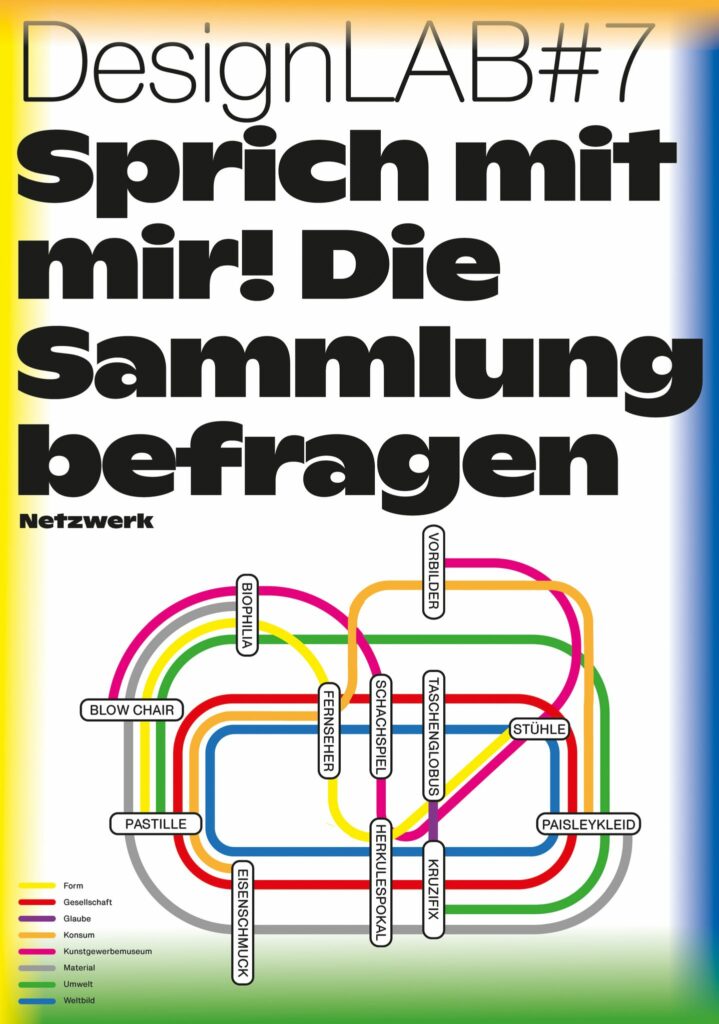

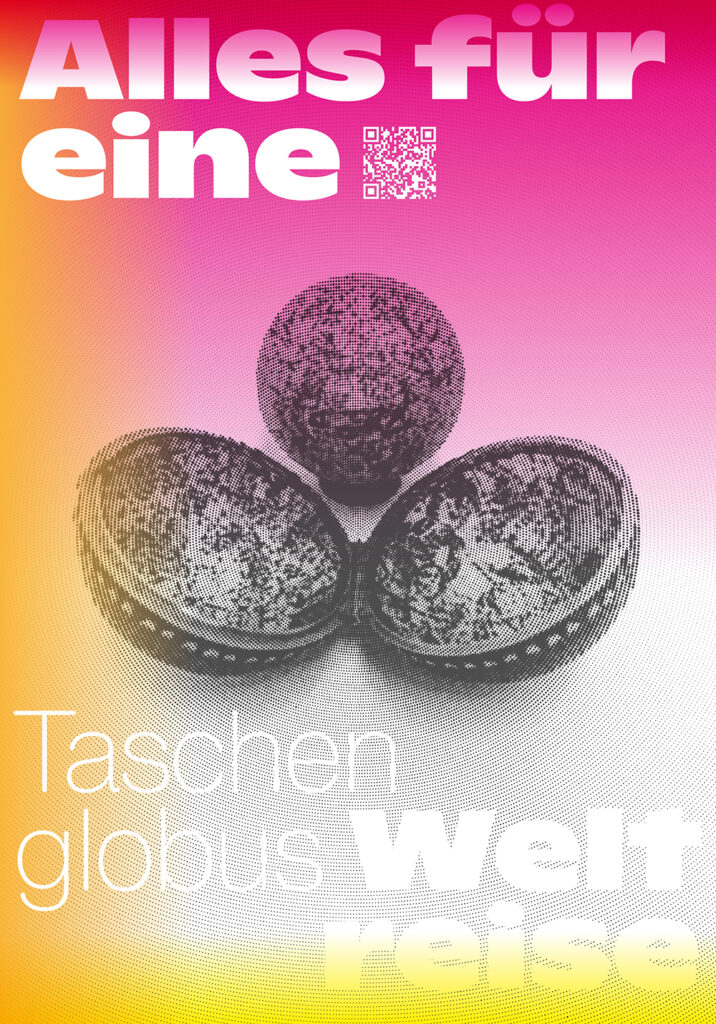

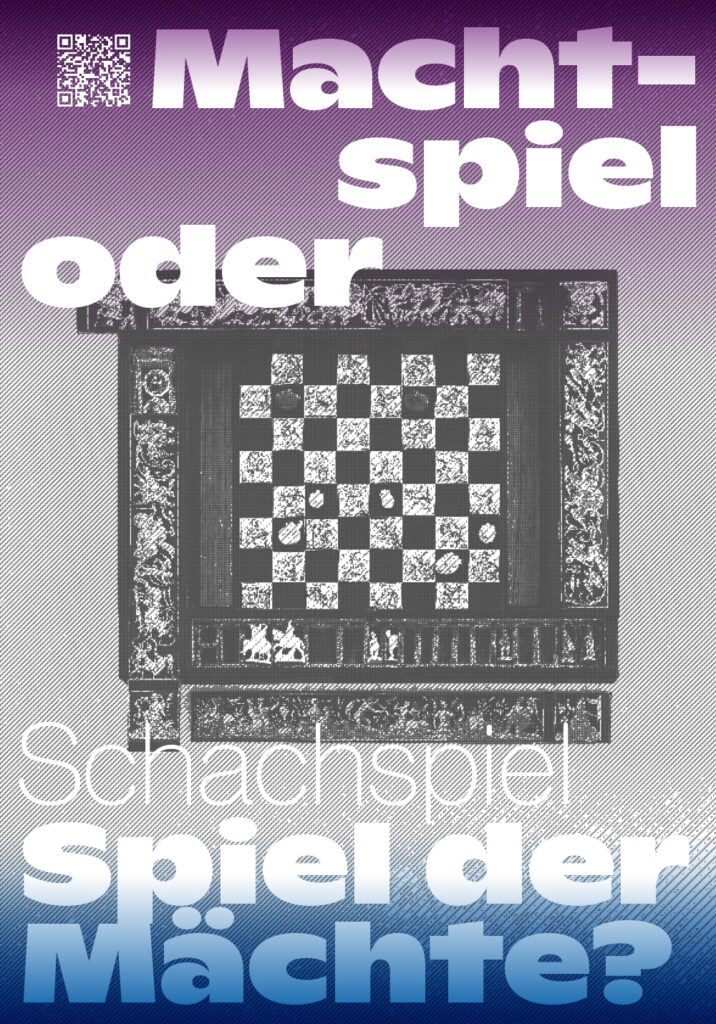

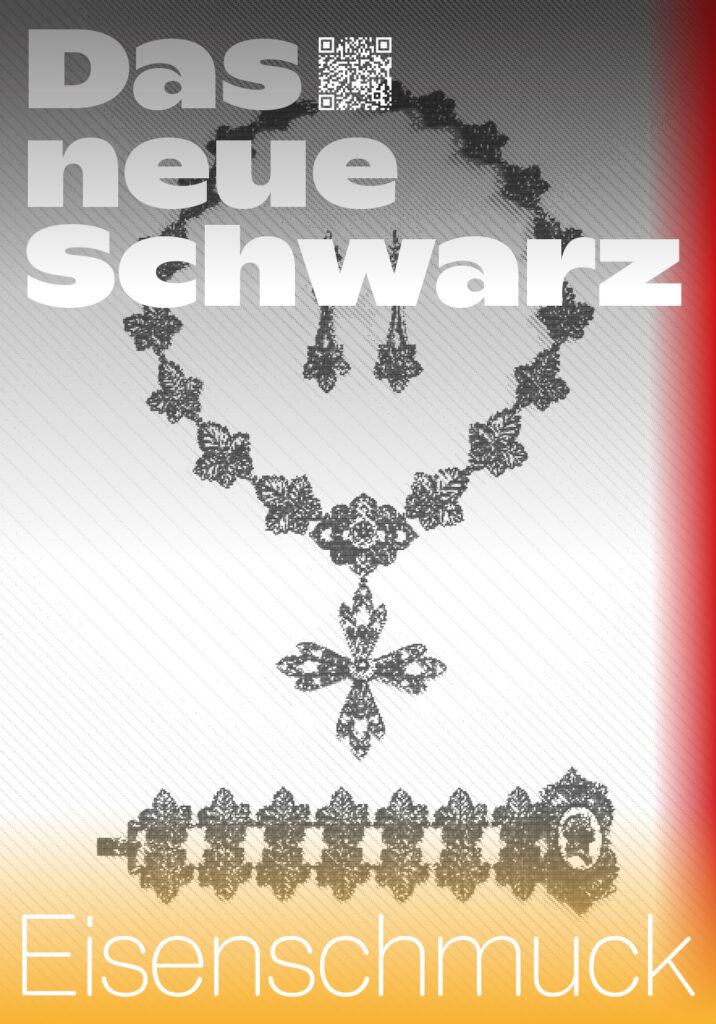

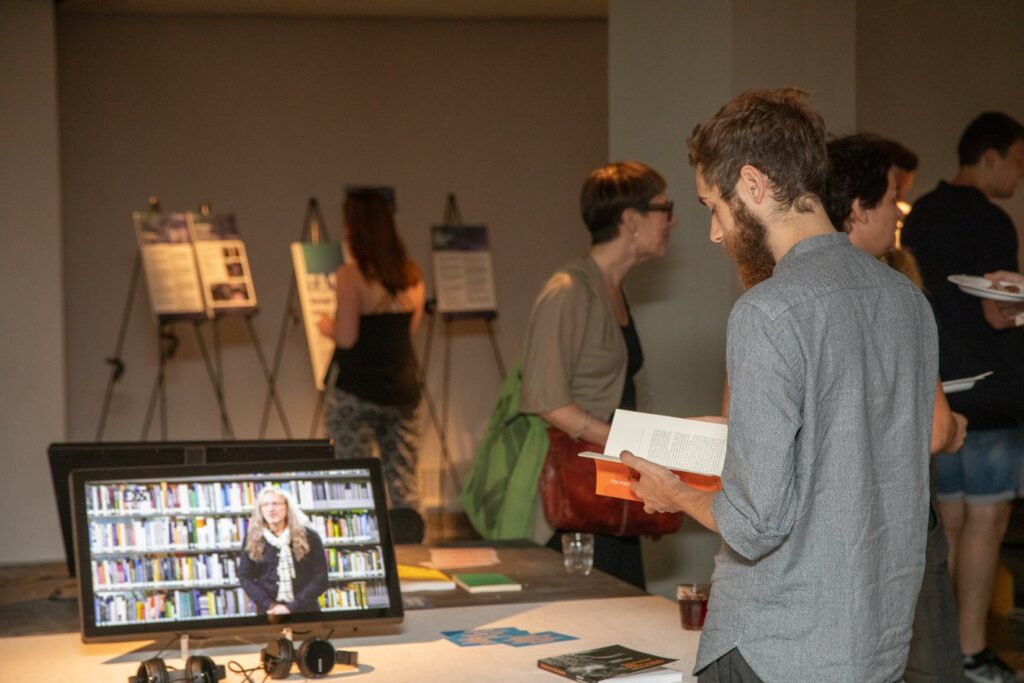

Design Lab #7 ‘Talk to Me! Consulting the Collections’ focused on the critical reflection of the hegemonic prerogative of interpretation and knowledge discourses of arts and crafts museums given that they still predominantly reflect the collection strategies, systematisations and epistemologies of the 19th century.[9] Students working towards a Master of Arts in Art Education, Curatorial Studies at Zurich University of the Arts addressed questions such as, Who decides what is collected? Which criteria form a basis for collecting?

To make museum objects speak for themselves, recognize them as echo chambers of the unseen and integrate them in a multi-perspective network of meanings are among the central tasks of museum education. At the same time, they present the greatest challenges with regard to reaching and appealing to a diverse audience. As a learning platform, the Design Lab thus also opens up a realm of possibilities for various actors, researchers, designers and students to reconsider museum and pedagogical practices and bring these into the contemporary discourse.

(Dr phil) is an art and design expert, exhibition organiser and author. Since 2017, she has been curator of design at the Kunstgewerbemuseum (Museum of Decorative Arts), Berlin. Prior to that Dr Banz was a freelance curator and, from 2011 to 2017, head of the art and design department at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg (Museum of Art and Design Hamburg). Banz has realised a number of well-regarded exhibitions, outreach projects and trade shows at the interface of design, fashion, art and crafts, including “Fast Fashion. Die Schattenseite der Mode”, “Food Revolution 5.0. Gestaltung für die Gesellschaft von morgen”, “Connecting Afro Futures. Fashion x Hair x Design” and “Retrotopia. Design for Socialist Spaces”. For the Kunstgewerbemuseum Berlin she established the series Design Lab and Design Talks, designed to open up the museum as a platform and experimental space for multidisciplinary design approaches and a critical discourse on socially relevant design issues. The Design Lab series was realised in 13 projects from 2019 to 2022. It was curated by Claudia Banz and facilitated by the Prussian Cultural Heritage Board of Trustees. Banz is a member of several juries, and her publications cover aspects of social design, material culture and decolonial collections.