The School of Arts and Crafts in Bratislava (ŠUR) – Educating anonymous, modern designers for practice

On 1 November 1928, when Bratislava’s Chamber of Trade and Industry offered three evening drawing classes in temporary premises, progressive professionals in the arts from all over Czechoslovakia sat up and took notice – even though this news would have normally only made the local daily paper. The Prague journal of the Czechoslovakian work federation, Výtvarné snahy (Art endeavours), supplied an explanation for the optimism with which so many suddenly looked to Bratislava: “These regular evening courses were set up as a trial for a future school of applied arts”,[1] reported the newspaper all but immediately. If one considers, moreover, that this story was about the very first public school of art on Slovakian territory, it becomes evident why such high hopes were riding on this initiative.

The launch of the drawing classes was preceded by attempts over several years to reform the arts and crafts, or folk art, of Slovakia. These were sustained above all by the Czech educational reformer and future director of the school, Josef Vydra, who in a first step was appointed head of the evening classes. To a large extent, it is to his credit that even before the planned Škola Umeleckých Remesiel (ŠUR, School of Arts and Crafts) was founded, its resolutely modern orientation had already been settled and was maintained until its closure in 1939. The decision about the foundation and curriculum of the school had already been made in 1927 when the central Czechoslovakian Ministry of Education invited all parties concerned to a meeting. Vydra was of course among them. Although it was agreed that Slovakia needed an art school, even at this stage the discussion was shaped by major discrepancies between progressive and conservative notions. Josef Vydra recalled the discussion as follows: “It was none other than the section head (of the Ministry of Education) Dr Zd. Wirth who spoke out against the creation of a new art academy and against the education of another ’artistic proletariat’. In his statement, he justifiably redirected the foundation and curriculum of the new school in Slovakia away from the envisaged academy of art to move along entirely different, practical lines.”[2] The character of the first art school in Slovakia thus established from the start a bias against the so-called artistic proletariat, that is, the graduates of art academies, whose training was unsuitable for practice.

Despite ambitious plans and first formal steps, the process of founding the school threatened to collapse. As long as an appropriate building remained unavailable, it was hardly likely that the evening classes would evolve into a fully-fledged school of arts and crafts. The decisive impetus came in 1930 when the apprentice schools of Bratislava were relocated to a large, functionalistic new building. Bringing the planned School of Arts and Crafts under the same roof as these appeared to be the ideal and only possible way to get hold of not only classrooms, but also well-equipped workshops. What is more, Josef Vydra, until then head of the Chamber of Trade and Industry’s drawing classes, was appointed director of both schools.

Even though integrating the planned ŠUR in the apprentice school building was in the first instance a more or less pragmatic step, for Vydra this alliance formed the point of departure for a promising experiment. While throughout Europe, the merger of art academies and schools of arts and crafts would lead to a new type of art school,[3] for Vydra the answer, in Slovakia at least, lay in establishing the closest possible link between the apprentice schools and a progressive school of arts and crafts. The first profited from a general improvement of artistic standards among their graduates because the School of Arts and Crafts was to serve as a “rigorous reformer of taste” for the apprentice schools.[4] The chief advantage for ŠUR was the possibility of recruiting from the apprentice schools students with previous experience in workshops. It is worth noting that at this time, there were some 2,500 apprentices in Bratislava.[5] With, among other things, the aid of a psychotechnical institute integrated in the school building, Vydra sought out from this mass the most talented individuals, who were offered an advanced course of art studies. This concept was enabled in part because until its closure, the School of Arts and Crafts functioned mainly as an evening school and the students thus did not have to give up their main studies. Besides the apprentices for whom the courses were intended, practically anyone with an interest in industrial arts, craft or advertising could attend. Depending on their skills, the students were divided into ordinary students with an apprenticeship diploma, exceptional students without an apprenticeship diploma and course participants.

Years later, Vydra continued to highlight the close link with the next generation of skilled craftsmen, as opposed to most art schools, which “merely worked with the next generation of students”. [6] He said: “Outside Bratislava, just three contemporary schools in Europe based their applied arts education on a previous knowledge of craftsmanship and an organisational link with vocational schools: the Bauhaus in Dessau, the School of Arts and Crafts in Brussels and the School of Arts and Crafts in Zurich, the latter two likewise in cooperation with apprentice schools.”[7] In 1935, when confronted with the claim that he had established the Slovakian Bauhaus in Bratislava, he confidently stated: “The school is not and does not aim to be a copy of the once so famous Bauhaus, even if it followed its development keenly from the beginning. On the contrary, today it appears to be the more viable model due to its link with the apprentice schools, through which it found a closer connection to industry and production than the Bauhaus.”[8]

The character of the School of Arts and Crafts in Bratislava was hugely influenced by the fact that Josef Vydra, as long as he maintained the practical and modern direction of the new educational institution, was more or less free to develop the curriculum as he saw fit and to select the staff he wanted. The lack of an art school tradition in Slovakia gave him the freedom to develop certain departments in the school without having to adhere to pre-existing structures. Under his leadership, the School of Arts and Crafts followed two basic lines. Firstly, by establishing departments that met the requirements of the curriculum of the apprentice schools[9] and secondly, by responding to the growing intensity of city life and the current needs of the retail trade, which were frequently neglected by traditional schools of arts and crafts. As such, just one year after moving into the new building, the school established not only crafts departments (ceramics, wood, fashion and textiles) but also advertising-orientated departments (painting, graphic design, photography) as well as special courses for children.

In the 1934/35 academic year, a metal department and a window display department were added to these. The latter in particular was an entirely new phenomenon which no other public school of arts and crafts in Czechoslovakia offered as an official subject.[10] But the final proof that Vydra’s concept for the ŠUR was in tune with the latest trends came in the 1938/39 academic year, when a film department was set up for regular day-time students. At the time, this was the first and only public film school in Central Europe. Had the ŠUR not closed shortly thereafter, this would have enabled it to compete with even internationally recognised educational institutions and attract students from all over Europe.

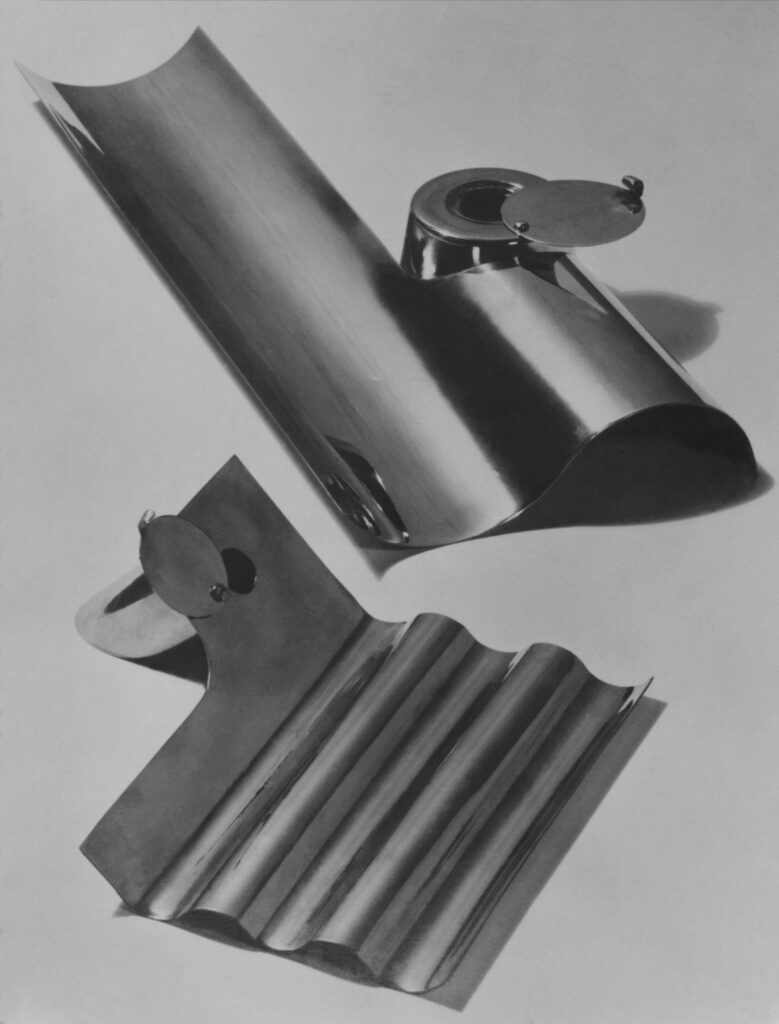

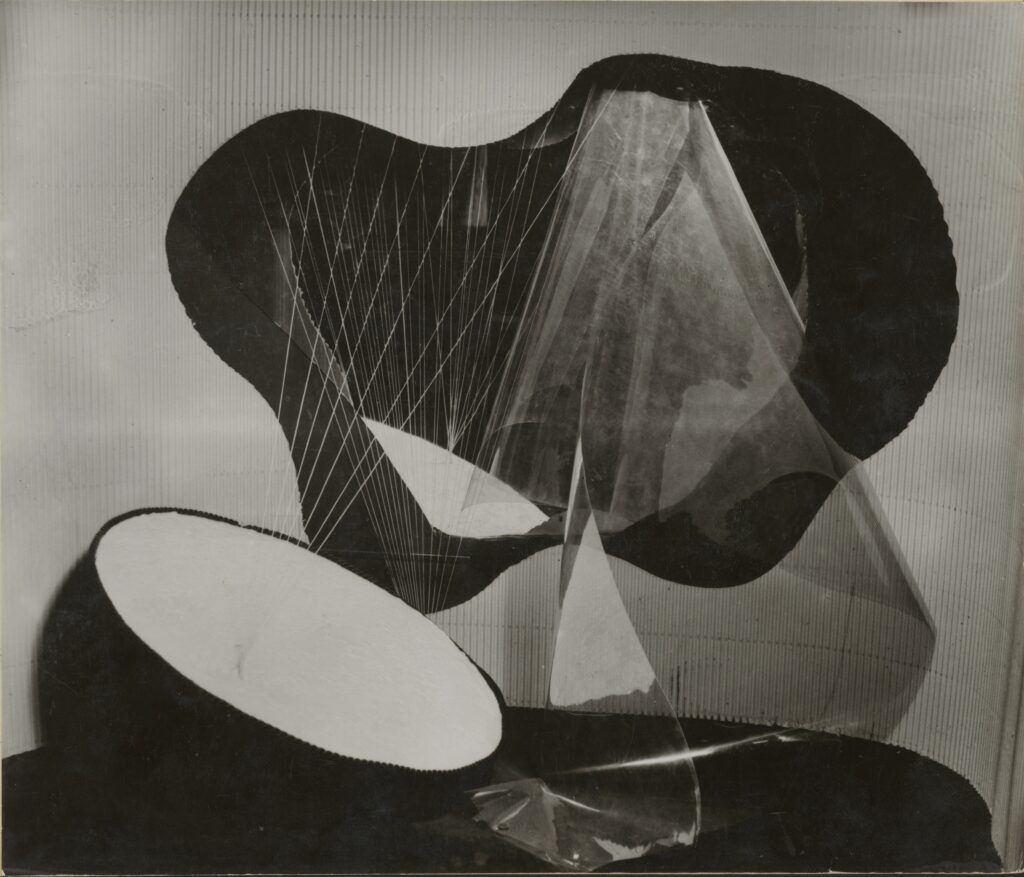

In this manner, until its closure in June 1939, the School of Arts and Crafts in Bratislava resolutely pursued the policy of not educating another so-called artistic proletariat. Josef Vydra’s art school model was not first and foremost about educating individual designers with artistic concepts of their own. Under the guidance of the school’s progressive faculty, the students were required to understand the principles of modern design (for which they had to attend the obligatory class called “contemporary taste”), to convert these into actual designs through practical work in the workshops and to ultimately put these into practice. At the same time, an emphasis was placed on experiments and on trying out new design approaches. The school’s students thus familiarised themselves with new media like photography and film, made collages and tried out new design and manufacturing methods.

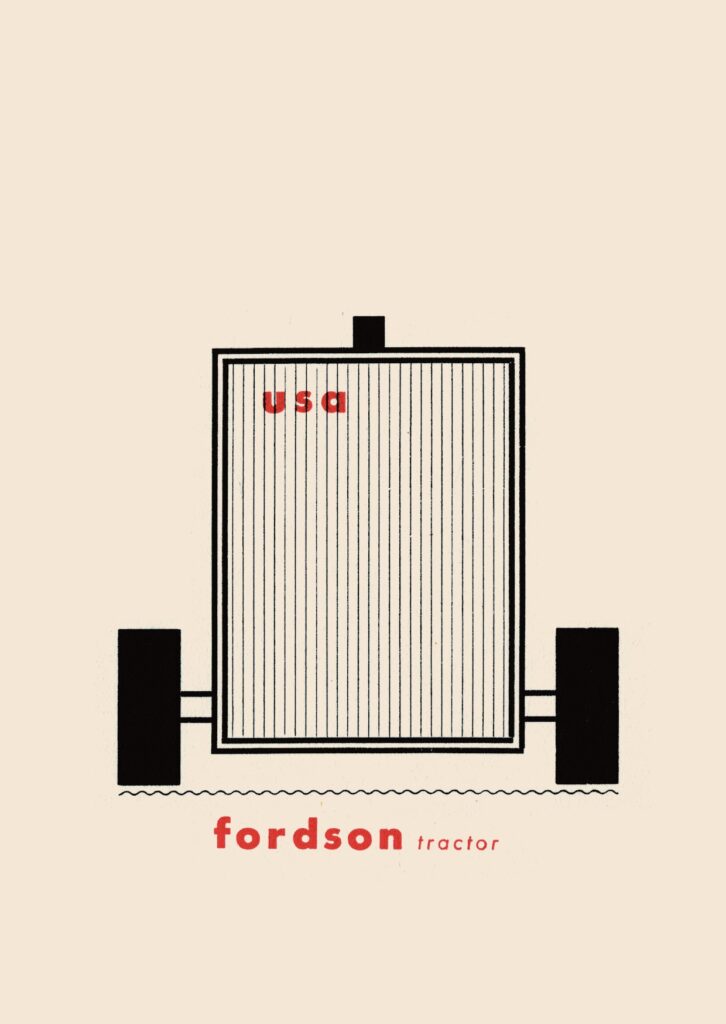

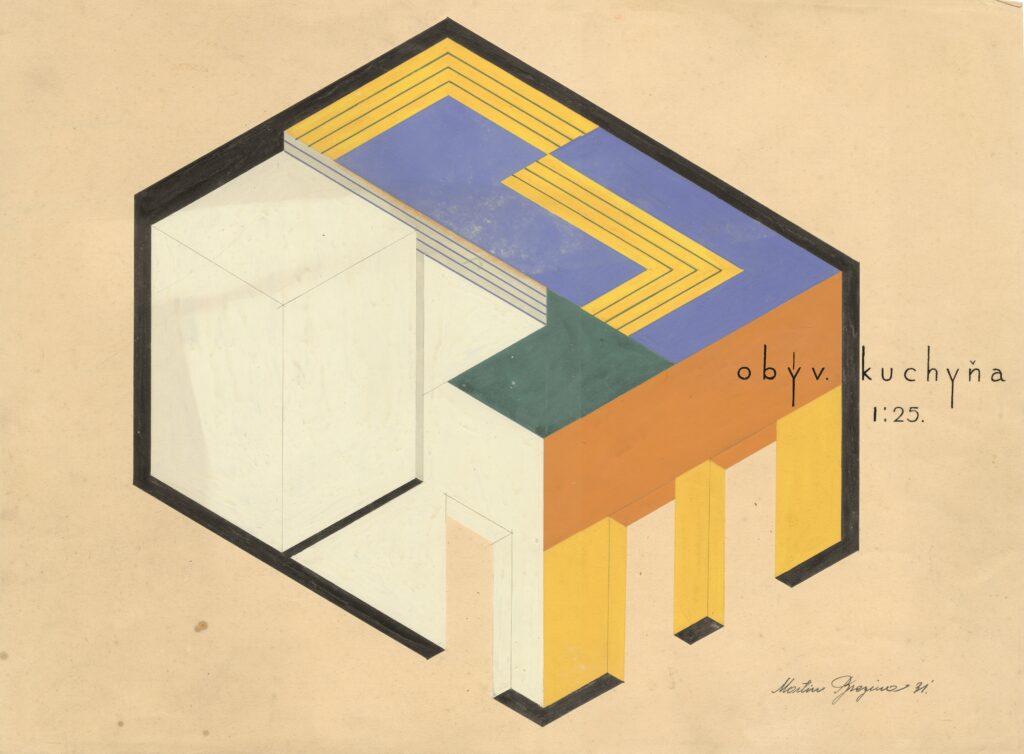

Modern techniques were also used to ameliorate a potential weakness in traditional drawing because the school, as we must always remember, was working with the next generation of craftsmen, not artists. With this in mind, so-called mechanised drawing was introduced. This method was developed at the school and utilised modern techniques like collage and frottage along with work with various templates to enable even less talented students or those without artistic training to follow a design process from beginning to end without the arduous work of drawing. Vydra introduced the method at the 1937 International Congress for Art Education, Drawing and Applied Art in Paris as follows: “This modern epoch demands modern methods of teaching, rapid and economical. Mechanisation is at the school the process which permits contemporary progress to be followed. Mechanised drawing reduces both mental and manual action.”[11] A few years later, he added: “These were simplified means of creative expression, suited to the shorter evening lessons.”[12]

Even such thoroughly avantgarde approaches were implemented at the School of Arts and Crafts in Bratislava to educate designers with a modern approach who, in anonymous work, were to contribute through practice to the modernisation of Slovakia. To borrow the words of the Czech art historian and expert in the reform of art education in Czechoslovakia, Lada Hubatová-Vacková: “In the context of the reform ideals, the new generation of apprentices and students at the ŠUR should form a rank and file of nameless craftsmen capable of changing society by means of design.”[13]

(*1981) gained a degree in literary studies. Since 2018, she has been working as a research associate, an administrator of the archive of the School of Arts and Crafts, Bratislava and a curator at the Slovak Design Centre. Her research areas include art journals of the interwar period, modern typography and the reform of art and arts and crafts education in Slovakia. She is the editor (with Simona Bérešová and Sonia de Puineuf) of the publications School as a Laboratory of Modern Life. On the reform of art education in Central Europe (1900–1945) and ŠUR. Škola umeleckých remesiel v Bratislave 1928–1939 (ŠUR. School of Arts and Crafts in Bratislava 1928–1939).