Tomás Maldonado and his visual methodology in the context of the basic course at Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm

In his lecture on the occasion of the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair, Tomás Maldonado (1922–2018) expounded on what may still rank as the cornerstones of the industrial designer’s profession. He foresees: ‘[…] the product designer will be a coordinator. It will be his job to coordinate the diverse requirements of production and use in close collaboration with an array of experts. In short, he will be responsible not only for maximum productivity, but also for the greatest satisfaction of the consumer in both material and cultural terms.’ (1)

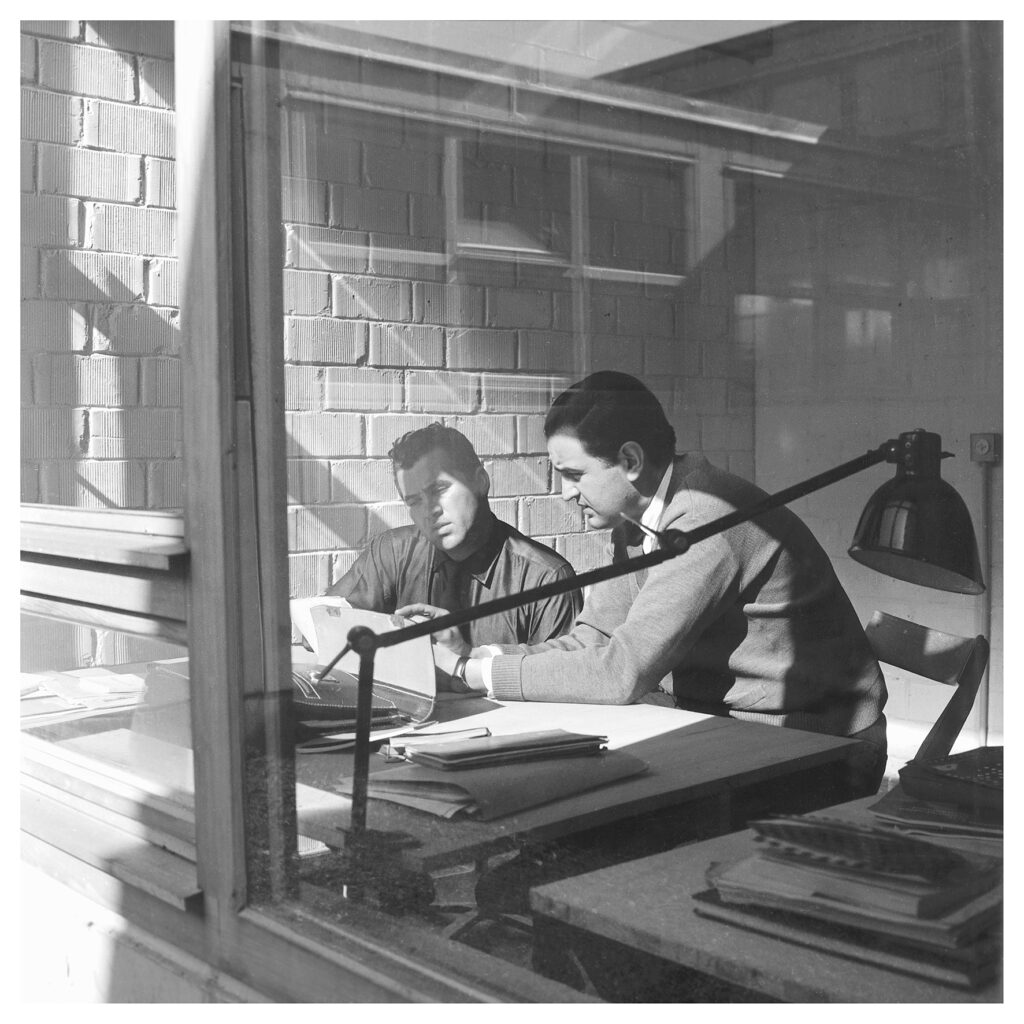

When Maldonado announced this prospect, he already had several years of teaching experience at the HfG behind him. He had arrived at the new school in 1954 at the invitation of Max Bill and by 1955, he was head of the basic course. [2] This was obligatory for students in the first academic year or those who had just arrived at the school.[3] When the HfG began teaching in temporary premises in August 1953, it was former Bauhauslers such as Walter Peterhans (1897–1960) or Josef Albers (1888–1976) who were asked to implement Max Bill’s plan of re-establishing the Bauhaus in Ulm. Helene Nonné-Schmidt (1891–1976) was also picked to support this objective. And even the founder of the preliminary course at the Bauhaus Weimar, Johannes Itten (1888–1967), was a guest lecturer at the HfG in late April 1955.[4]

Otl Aicher (1922–1991), co-founder of the HfG together with his later wife Inge Scholl (1917–1998) and Max Bill (1908–1994), had rejected the name Bauhaus Ulm for the HfG early on, during the founding phase. They decided instead to call it School of Design, thus adopting the subheading of the Bauhaus Dessau.[5]

The question of which pedagogical direction the HfG should take was discussed in the correspondence between Bill, Aicher and Scholl as well as in Bill’s exchanges with the teachers he wished to gain for the school. In a letter to Bill, Walter Peterhans speaks vehemently against the experiment, takes a swipe at the ‘Bauhaus kindergarten (or Bauhaus retirement home?)’ and its pedagogy and is ultimately fundamentally opposed to Bill’s objectives.[5]

Josef Albers summarises his experiences of the two courses held at Ulm in a report to the Office of the High Commissioner for Germany, whom he finally recommends further support the ambitious project.[6] In his view, the teaching is founded on ‘vision and articulation’. He rejects ‘self-expression’ at the outset of an arts education, using a comparison with language to explain his rationale: To express oneself in a foreign language without the essential vocabulary is impossible; the same is true in the artistic field of endeavour.[7]

To return to the opening quotation from Maldonado’s Brussels speech, it behoves us to ask which demands might be made of the designer as coordinator, which range of subjects are required to prepare him for this role.[8] In Ulm, the school administration answers this question by introducing subjects such as semiotics or mathematical operational analysis, to name but two.

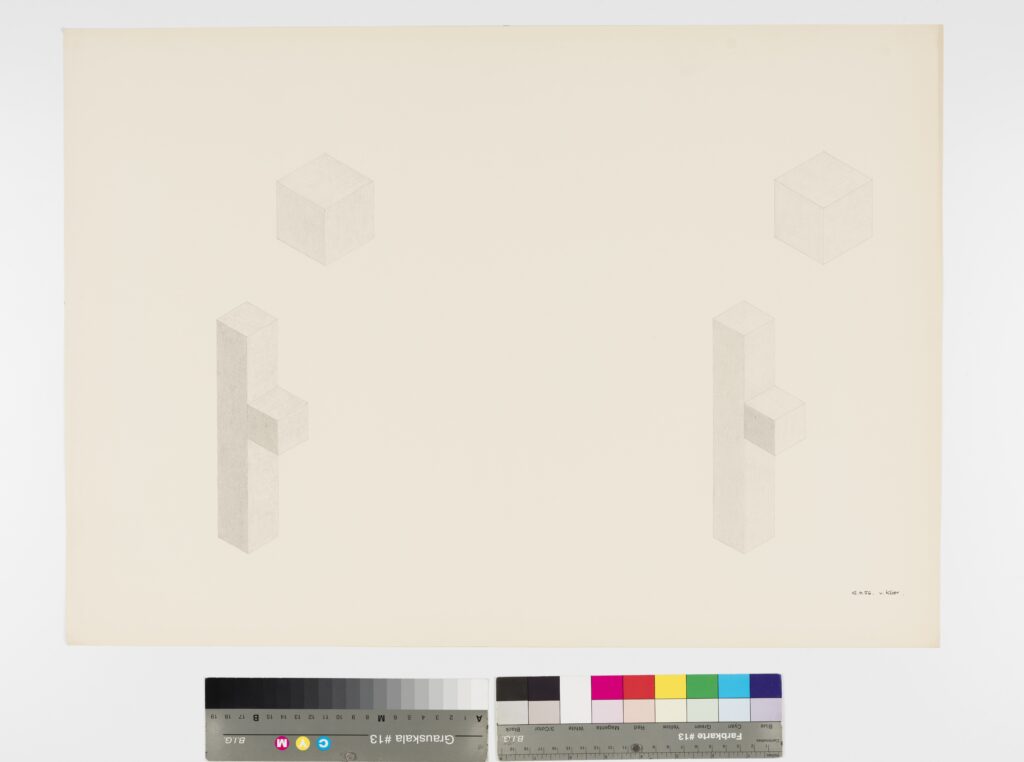

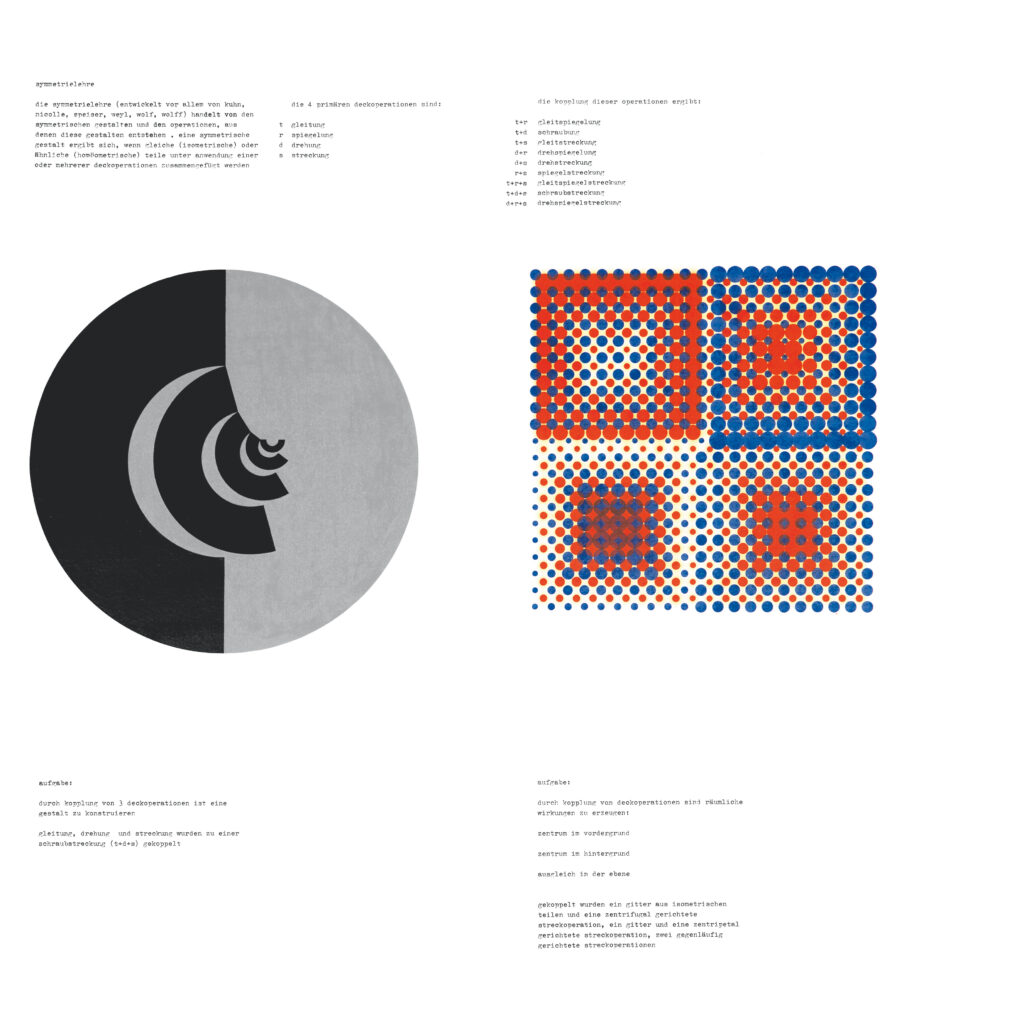

On the basic course, this new approach is tangible as early as 1955. Tomás Maldonado names his component of the basic course ‘Visual methodology’, presumably in reference to Peterhans’s ‘Visual training’, which the latter introduced in Chicago in 1938/39 and taught in Ulm in 1953.[10]

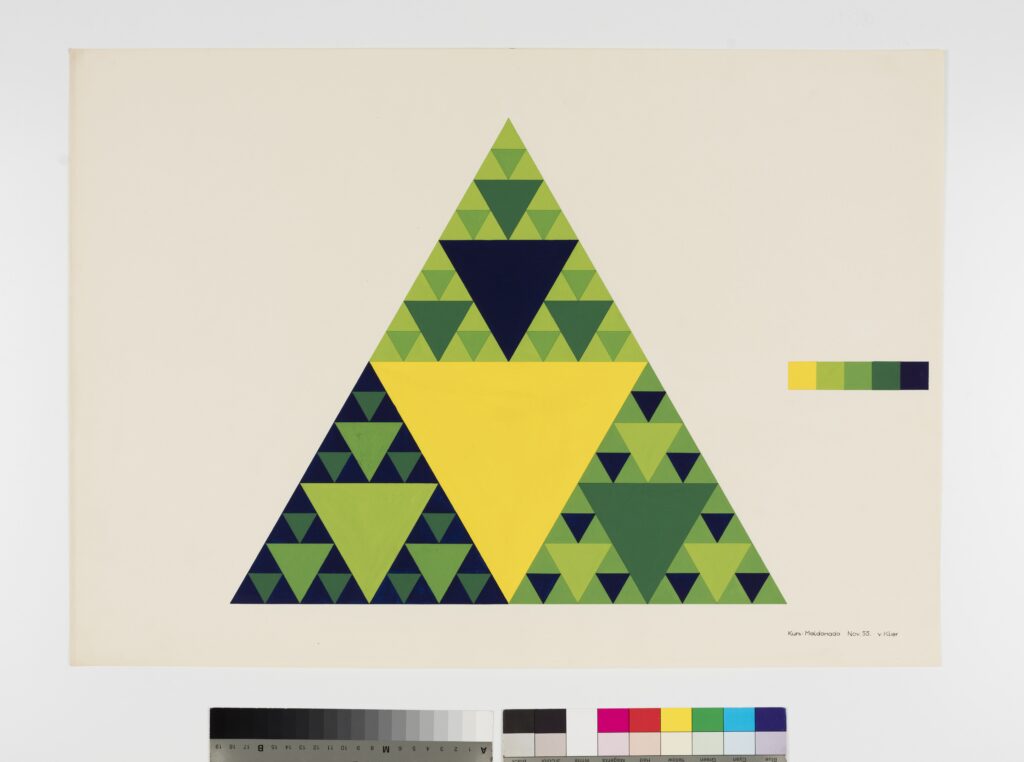

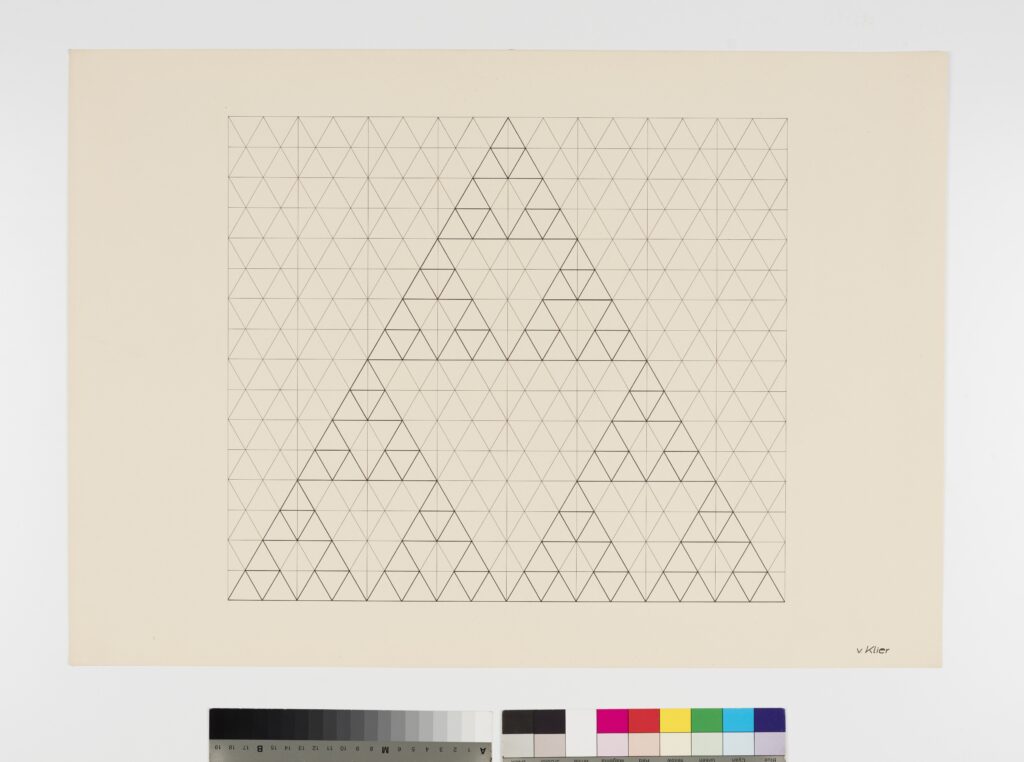

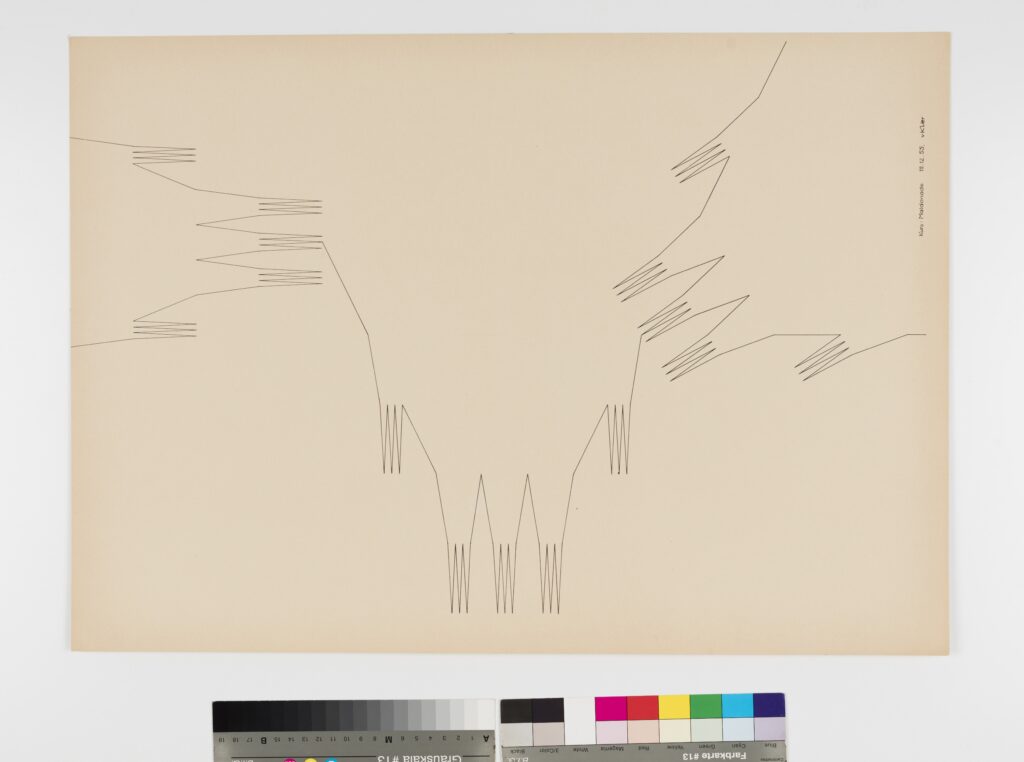

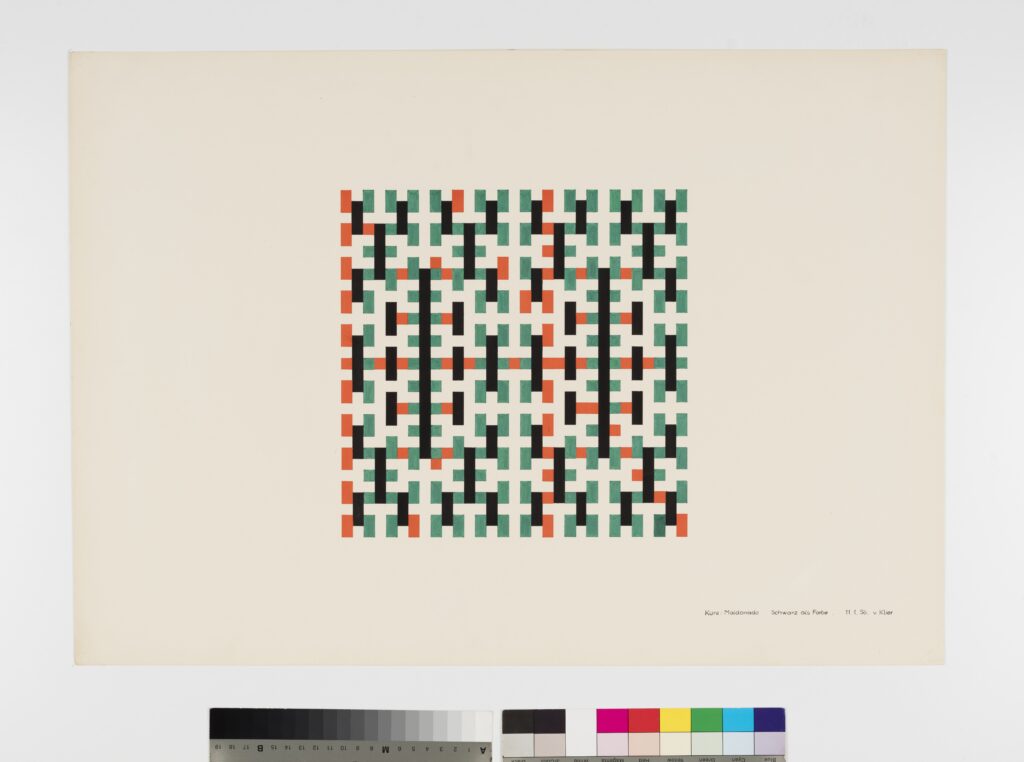

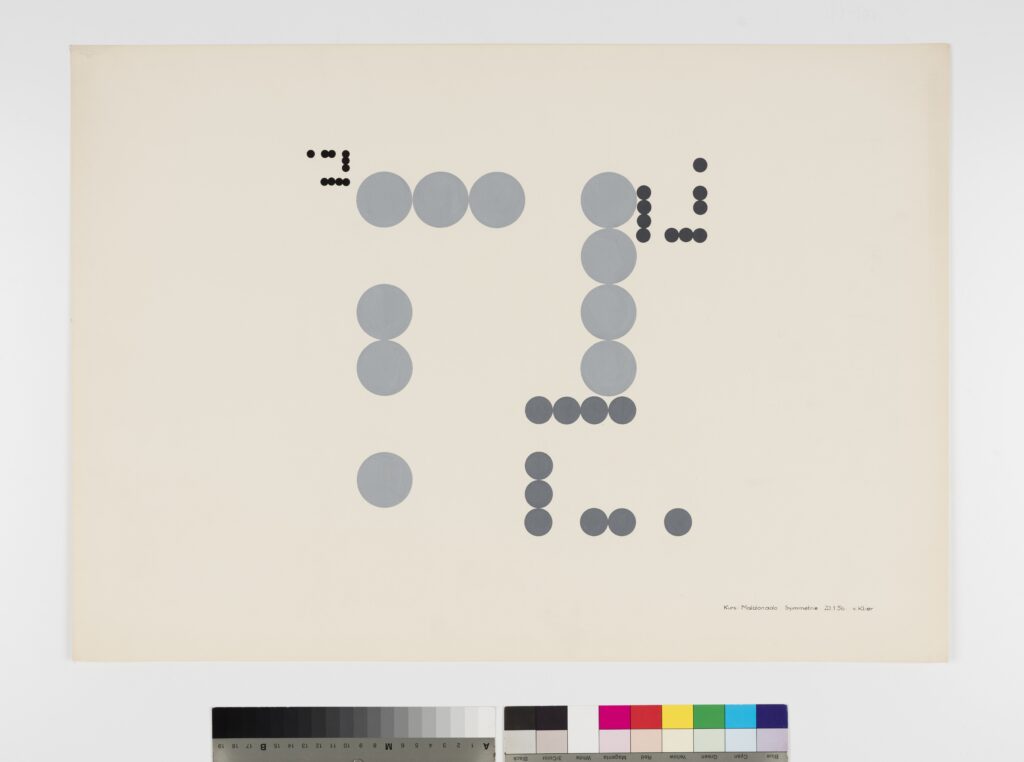

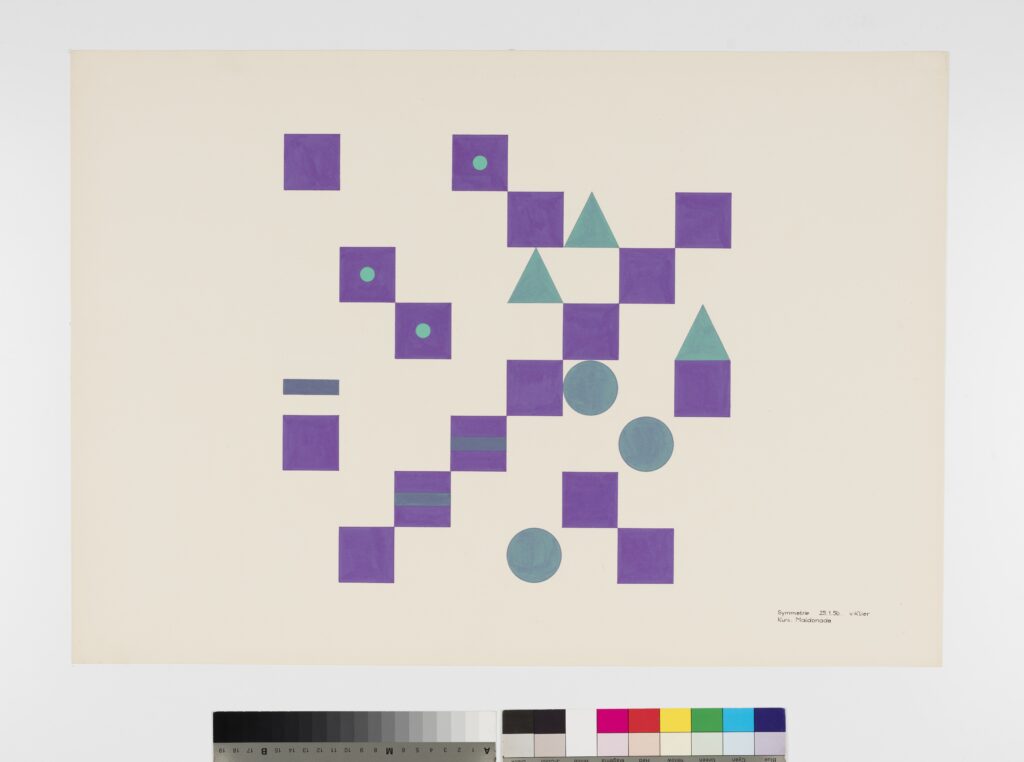

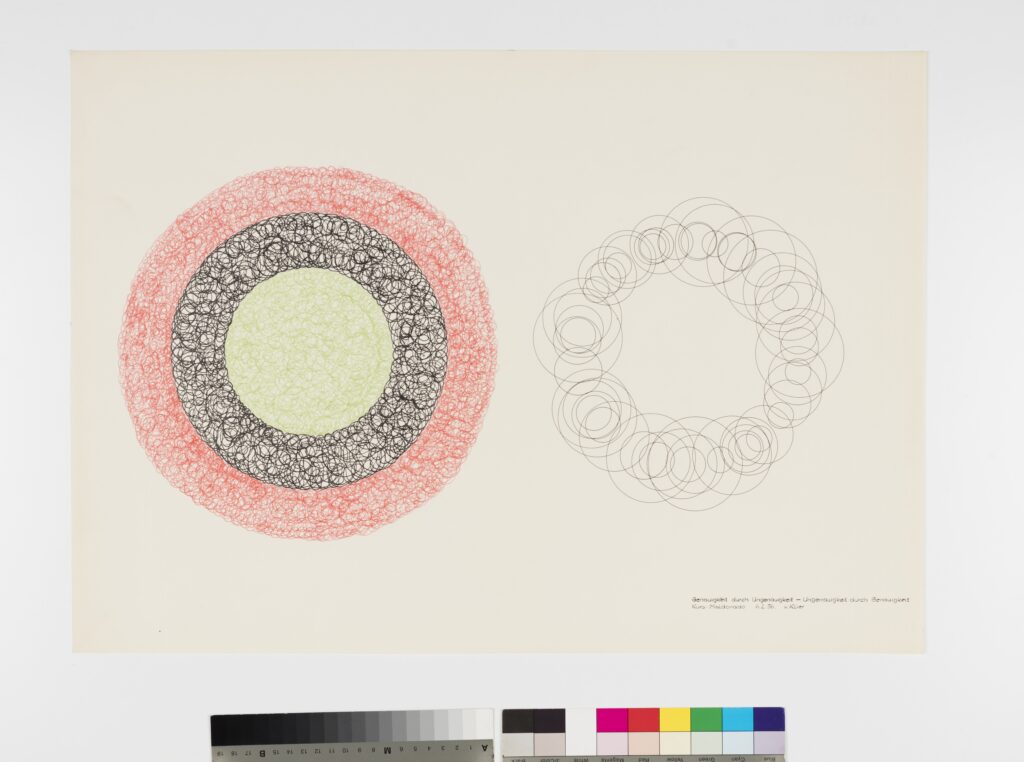

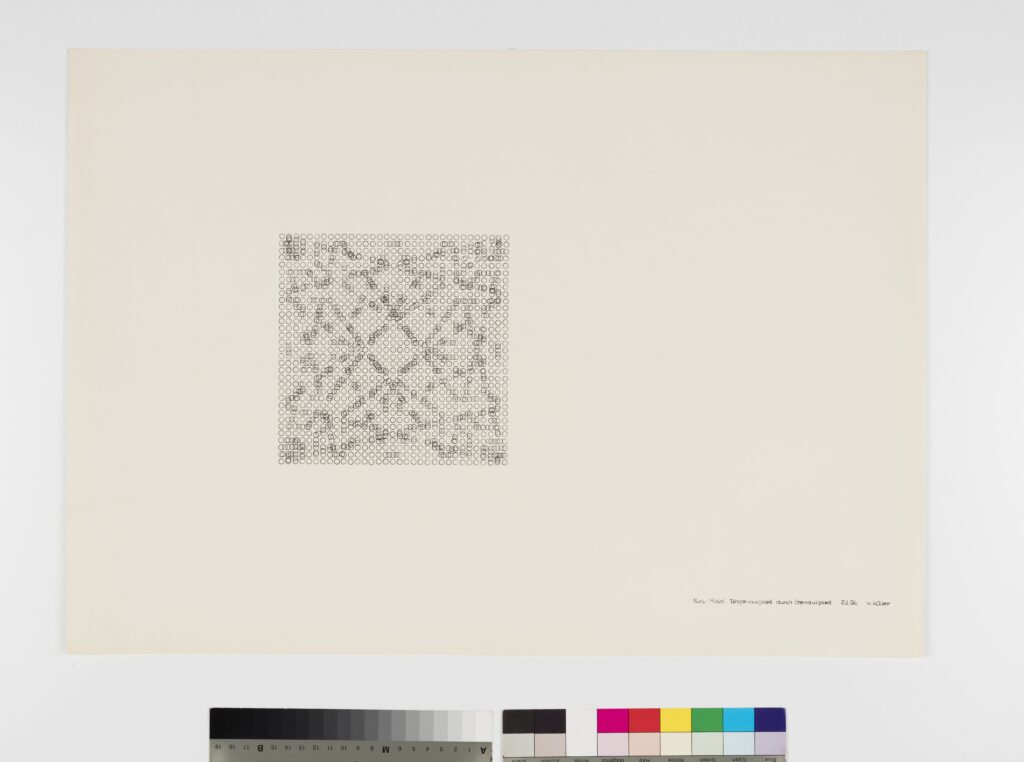

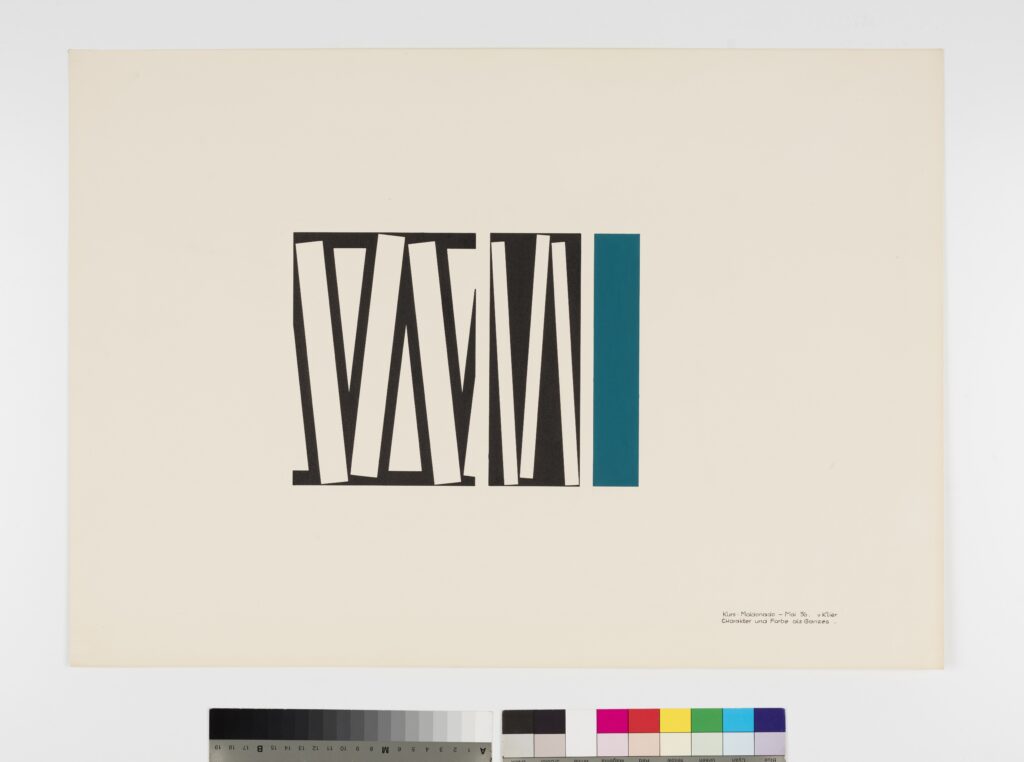

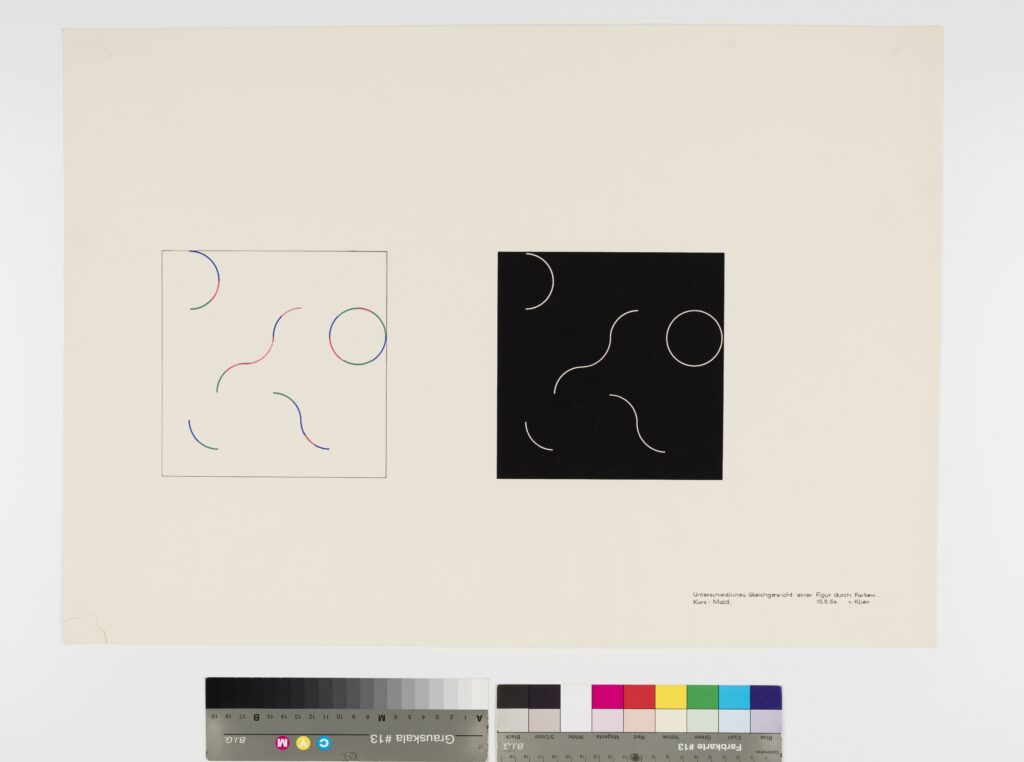

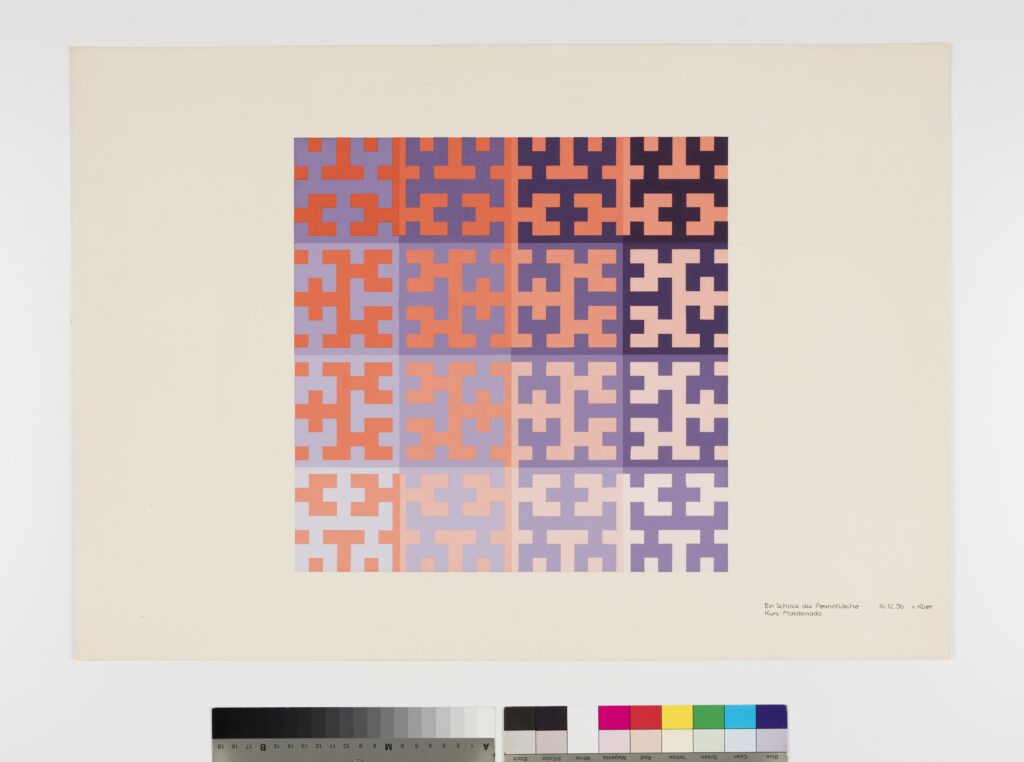

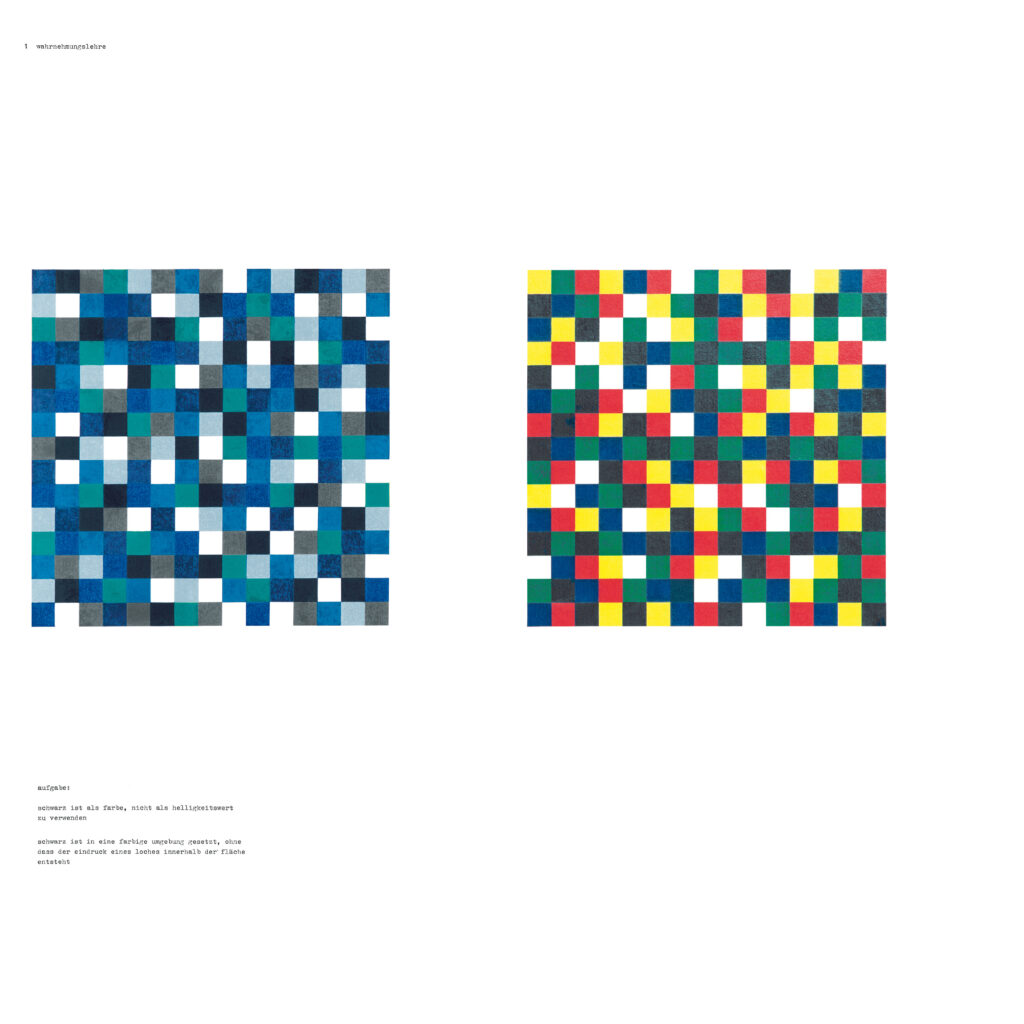

The tasks devised by Maldonado were clearly set out under the heading grundlehre 1955/56’ by the student Klaus Franck (1932).[11] Most of the tasks are described in a short text, some have added explanatory sketches. Franck numbered the sketches from 0 to 8. Briefly, they are: ‘0 spinsky triangles’ [!], ‘1 peano area’, ‘2 weierstrass system’, ‘3 black as colour’, ‘4 symmetry’, ‘5 precision – imprecision’, ‘6 four exercises after ames’, ‘7 five tasks on “equilibration of areas through colour and structural treatment”’, ‘8’, another group of three exercises without a common heading.[12]

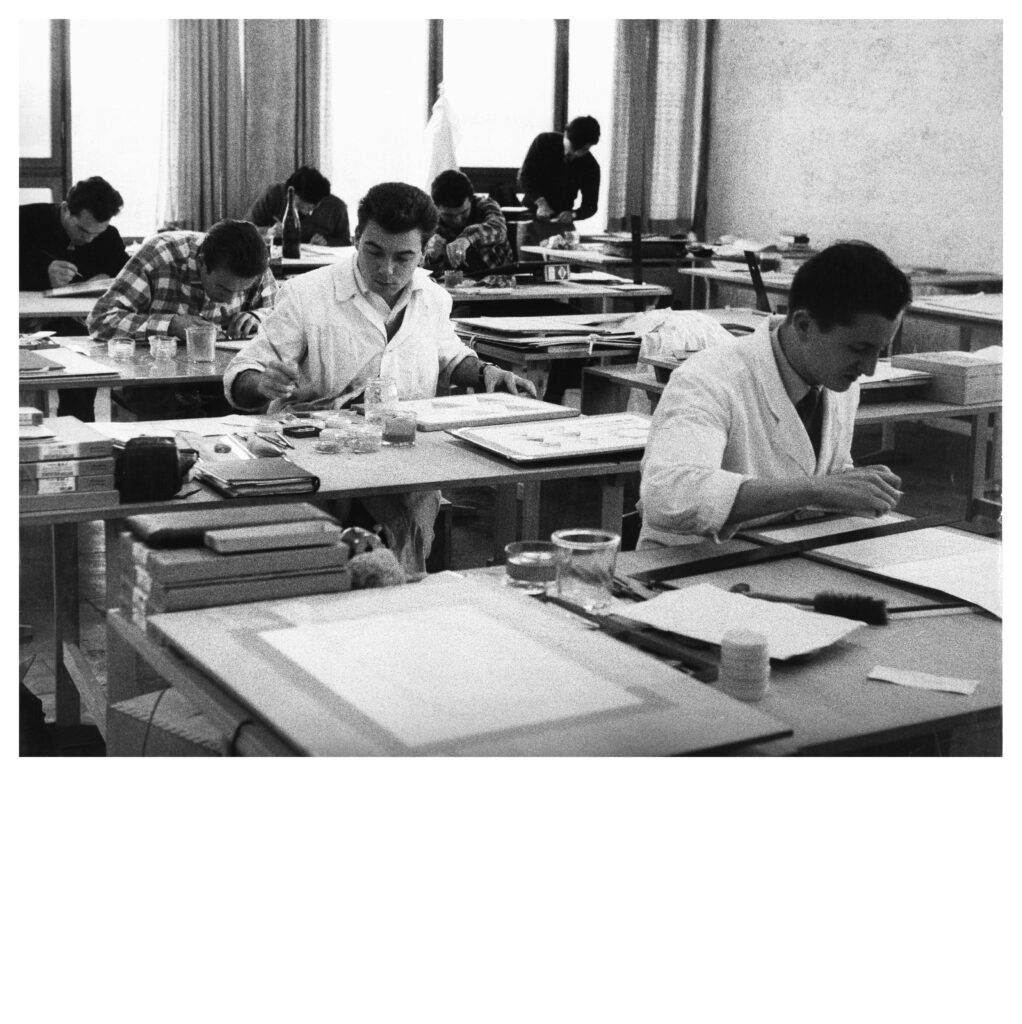

The first study year, i.e., the basic course year, was dedicated to non-applied design – despite the students’ desire to actually design something. The first priority was to learn about the foundations of design without having to think about utilizing the acquired knowledge.[13] Up to 1961, this basic course was the same for all; only afterwards was it decided who would be accepted in which department. From 1961, the general basic course was discontinued and organised in the individual departments, thus adapted to suit the respective subject (product design, visual communication, industrialised construction).

Tomás Maldonado, according to Aicher a ‘painting drop-out turned theorist’,[14] was preoccupied with theoretical questions even in Argentina, as William S. Huff verifies.[15] Huff,[16] enrolled at the HfG in the 1956/57 academic year and an enthusiastic student of Maldonado‘s concept, refers to the four-volume book The World Of Mathematics, which is found in the surviving school library at the HfG-Archiv Ulm to this day.[17] These volumes include the essay ‘The Crisis in Intuition’ by the mathematician Hans Hahn.[18] This text begins with a critique of Immanuel Kant and his bias towards intuition and consequently cites numerous examples to prove that the then prevailing problems of mathematics could not be resolved through intuition. The evidence Hahn puts forward includes Weierstrass’s concepts of a curve ‘that at no single point has a specific gradient, a specific tangent’ (p. 48f) and Giuseppe Peano and the continuous curve in the two-dimensional surface (p. 51f). The method of construction of a Peano curve, shown in the tasks completed by the Ulm students, is depicted in this essay.[19] Even the ‘curves, all points of which are branch points’ after the Polish mathematician W. Sierpinski, whom Klaus Franck wrongly named ‘spinsky’ in task 0, is mentioned by Hahn.[20] Franck lists the Peano curve under Task 1, the Weierstrass curve under task 2. While this requires in-depth analysis to prove, it does indicate a pedagogical thrust that he then summarised in his 1958 lecture like this: ‘We now know that theory must be combined with practice, and practice with theory. Today, action without knowledge is as impossible as knowledge without action. Operational scientific thought has vanquished the naive dualism, the pseudo-problems that so perturbed the first pragmatists.’[21]

While this may be regarded as a critique that indirectly refers to the correspondence between Bill and Peterhans, when and to what extent Maldonado and Bill discussed these questions at the time admittedly remains open to question.

The lecture at the congress in Brussels mentioned at the start is of such critical importance for the HfG’s further development because in it, Maldonado explained at length why the Bauhaus could no longer be a role model for the school. He wrote: ‘This educational philosophy is now in crisis. It is not able to absorb the new relationships between theory and practice established by the latest scientific development.’[22]

1958 is the year in which the HfG presented a balance of its activities for the first time since its founding in 1953. On a total of 84 panels set up in the canteen of the school building designed by Max Bill, an exhibition designed by students and lecturers documents the organisation and structure of the institution, the individual departments and the contents of their classes, and more.[23]

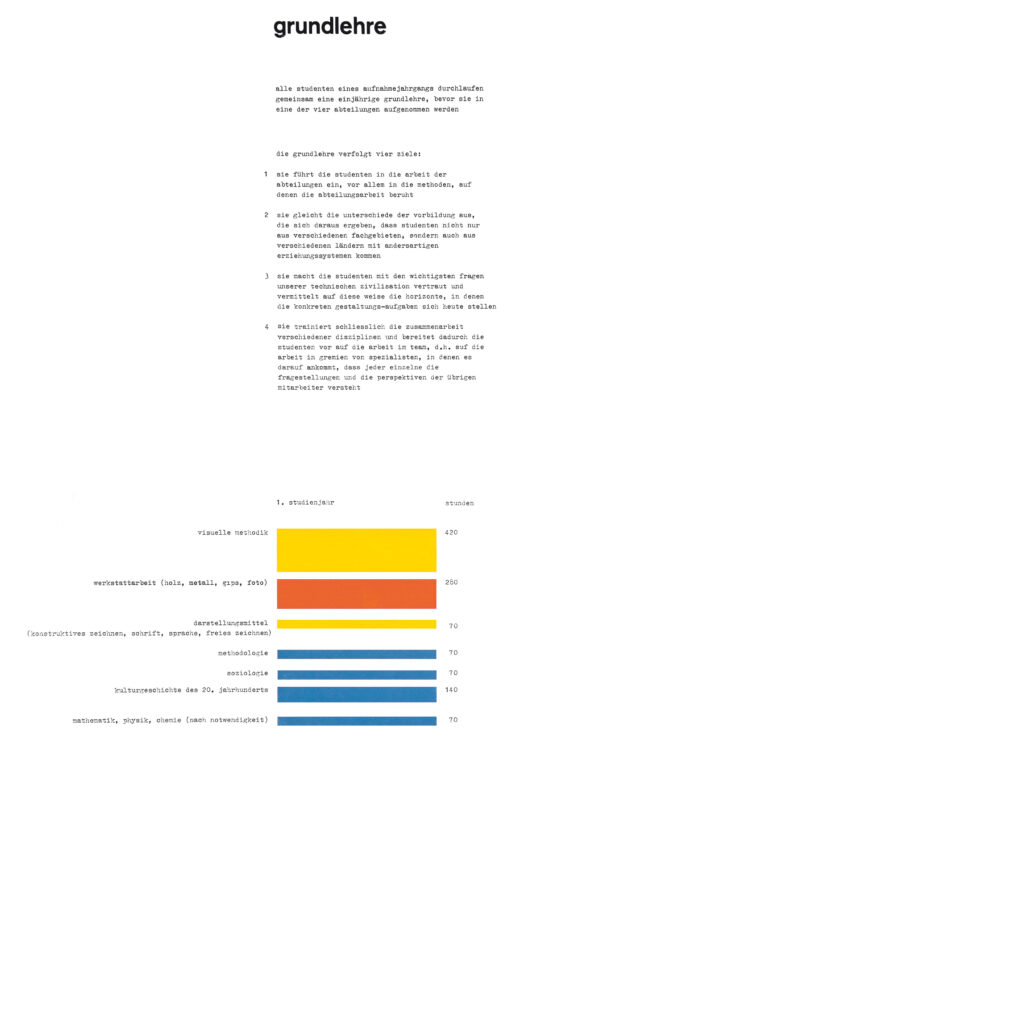

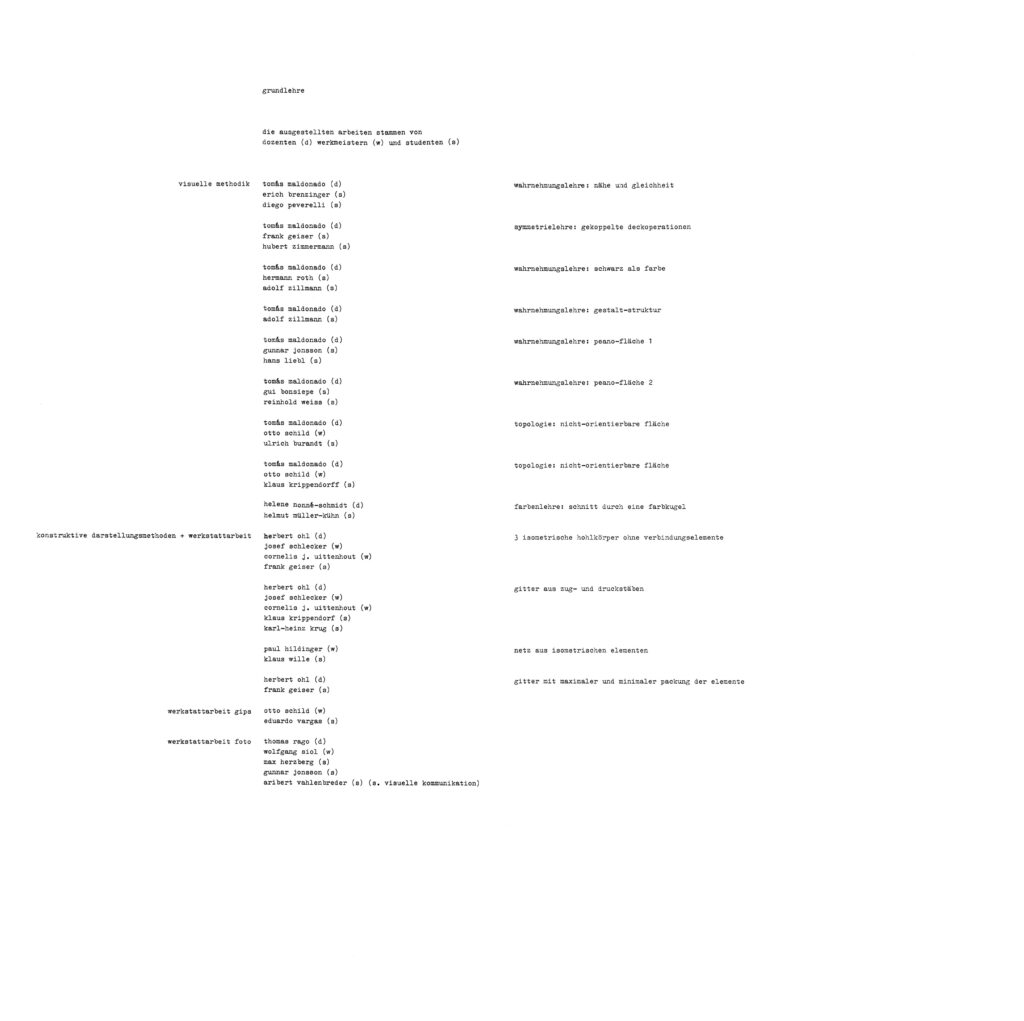

Eleven of these panels are dedicated to the basic course.[24] Panel 97 shows the objective and the proportion of teaching given over to each subject. The basic course takes place during the first academic year and must be completed before the students can be accepted in one of the (in 1958) only four departments. The text lists four objectives. Firstly, the basic course was to serve to introduce the students to the work of the departments, especially the methods that are applied in these departments. The second objective aims to compensate for the students’ different background, e.g., in terms of subjects studied or countries with different, unfamiliar education systems. The third objective ‘familiarises the students with the major questions of our technological civilisation and conveys in this way the horizons for the real design tasks of today’. The fourth objective addresses interdisciplinary collaboration, which endeavours to ensure that ‘each individual understands the challenges and perspectives of the other collaborators’. The last two objectives articulate the concept that will later become part of design history as the ‘Ulm model’.[25]

Visual methodology was regarded as a major subject, as the allocation of class hours shows. It was allocated 420 hours, the work in the workshops by comparison only 280. Means of representation, which included design drawing, typography, language and fine art drawing, were allocated only 70 class hours, as are methodology, sociology and a range of scientific subjects, namely mathematics, physics and chemistry. Nonetheless, 140 class hours were allocated to 20th century (sic!) cultural history.

Visual methodology, which is referred to on panel 100 as a main component of the basic course, is broken down on panels 100 to 107. On panel 100, the subject is described in more detail: ‘Visual methodology is the principal subject of the basic course, the purpose of which is to train the students to adopt a deliberate and controlled approach to design processes. In doing so, the ideas of the following scientific disciplines are to be turned to account:

1 cognition theory

2 symmetry theory

3 topology

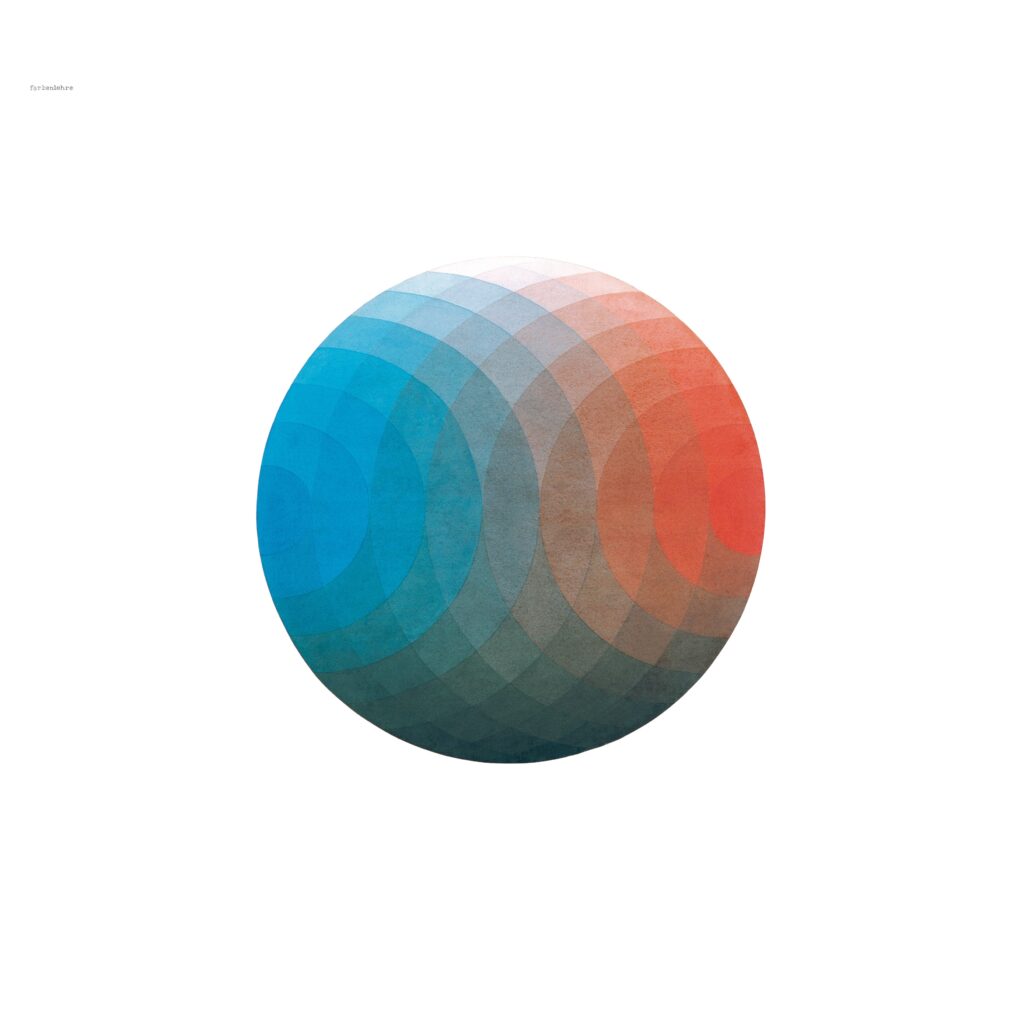

[…] The course begins with elementary exercises from the field of visual perception. The tasks are resolved by utilising the findings of modern cognition theory.’

Following this text, the other panels are dedicated to the following subjects: symmetry theory (T 101), cognition theory (T 102), design [and] structure (T 103), cognition theory (T 104), topology (T 105 and 106) and, finally, colour theory (T 107).

There is no sign of the Bauhaus-inspired tasks from the classes of Josef Albers or Walter Peterhans. Only the colour theory taught by Helene Nonné-Schmidt comes to light, in the ‘Section through a colour sphere’ on panel 107.[26] The renunciation of the Bauhaus, even in the basic course, is now finally complete.[27] For the new designer, the way forward lies open.

Klaus Franck, overview display of the tasks set by Tomás Maldonado, academic year 1955/56

The tasks are enumerated from 0 to 8.

maldonado course – basic course 1955/65 – klaus franck

0

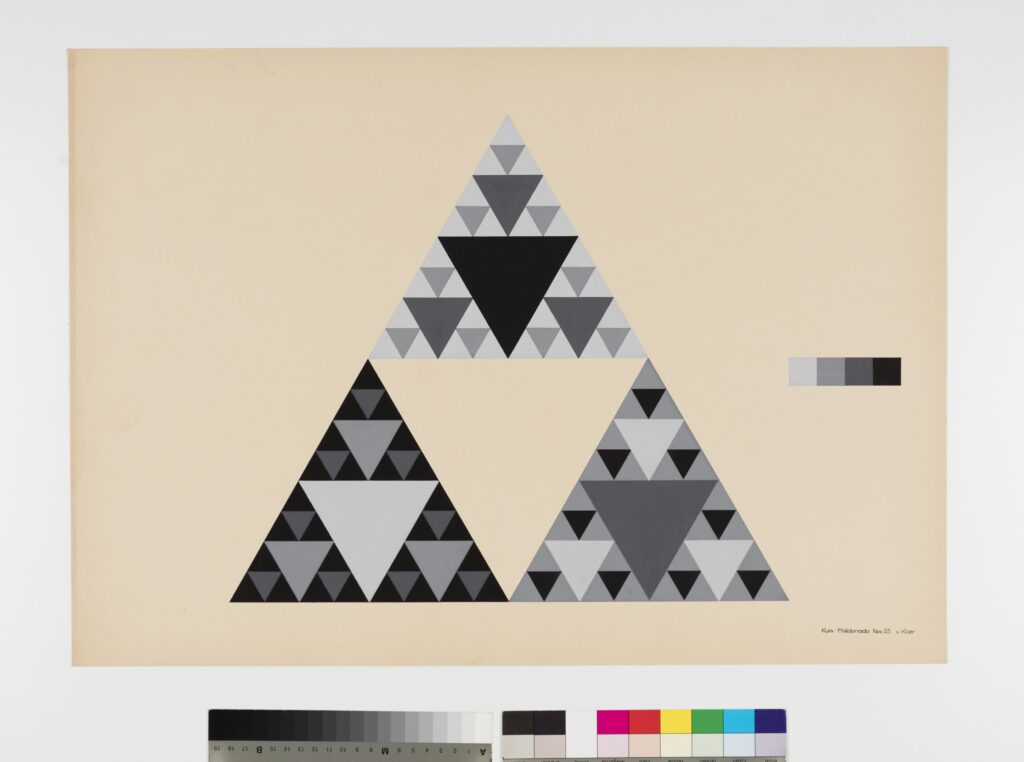

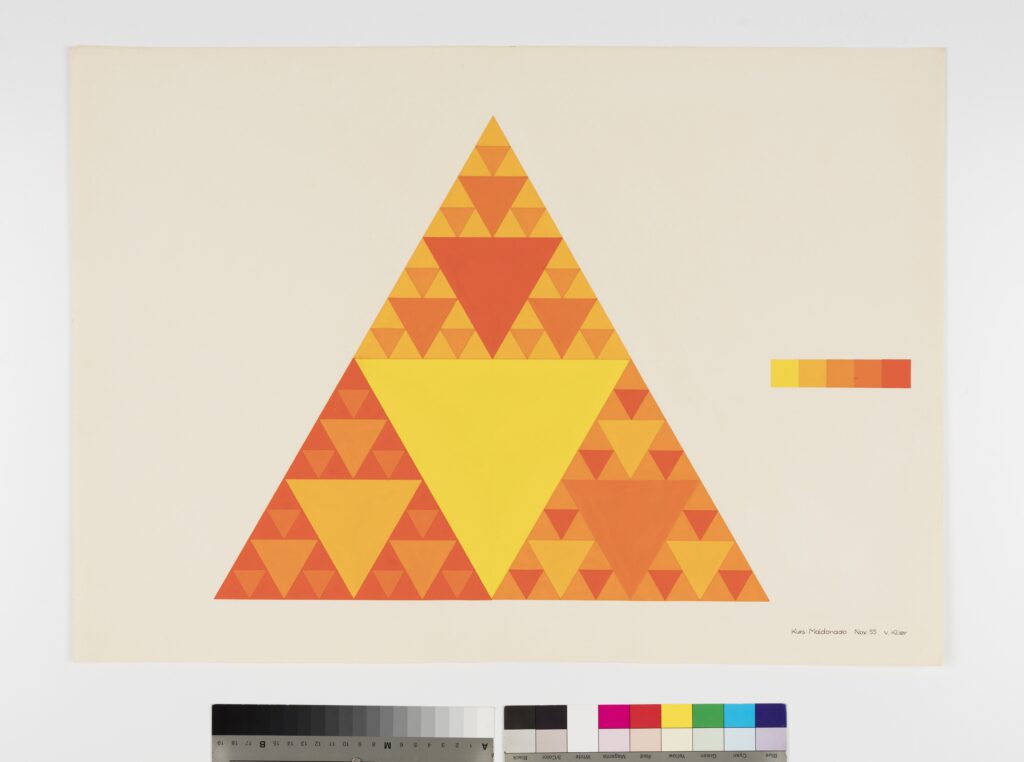

SPINSKY-TRIANGLES

— 01 schema: the uniform colour grades specified in the scale are entered in triangles A, B and C in 3 different configurations. it appears that the optical effect of the colour grades differs in each of the 3 triangles and does not correspond with the scale.

— 02 grey-black

— 03 rectification grey-black: in rectification, the colours in the triangles are optically aligned with the grades of the scale and obtain even increments.

— 04 yellow-red: rectification by d. gillard

— 05 blue-white

— 06 blue-yellow

1

PEANO AREA

— 11 4096 areas; juxtaposed 64 times the module according to schema c

2

WEIERSTRASS SYSTEM

— 21 based on an equilateral △ with 8 cm side length [!] the construction was arranged so that the zig-zag lines fill a 32 • 32 cm square. colour gradient: background: white-yellow-white / line: pink-purple-light blue

— 22 colour gradient: a) white-red-white: background / line: green; b) white-blue-white: background / line: orange

3

BLACK AS COLOUR

— 31 for composition, peano area was allied to c. the 32 • 32 square was divided into 4 vertical strips, the second of which is the inverse of the first in terms of colouration. The colours are interchanged in the third and the fourth is the inverse of the third. / Black should not seem like a ‘hole’ but have the effect of a colour.

4

SYMMETRY

— 40 shows the schema for 41 and 42 with an equilateral △ s = 1 cm a similarity transformation is executed in such a way that one side length has a ratio of 2:3 against the next biggest. The transformation ranges from 1:1½ to 8:12. the second picture shows the inscribed circles of the triangles

— 41 transparency through crosshatching. The described system is rotated by 180° and overlapped. the direction of crosshatching is rotated by 90°.

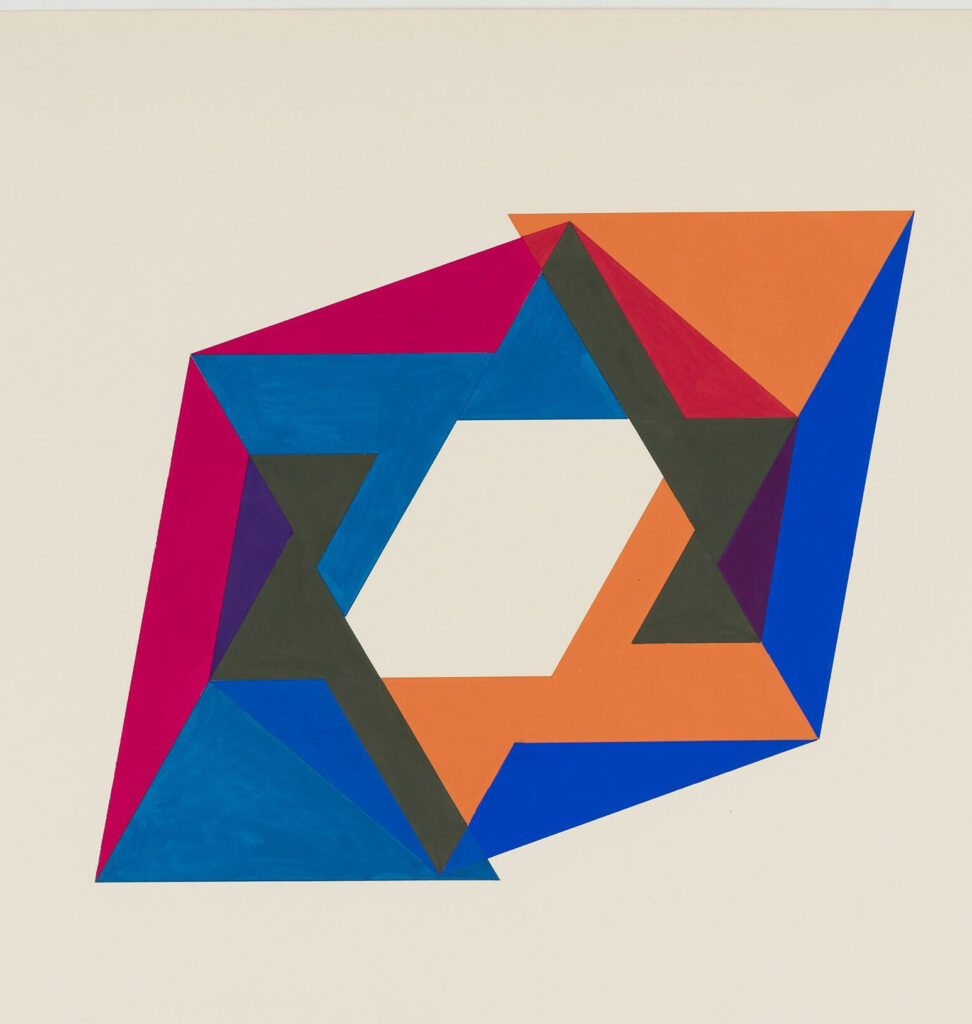

— 42 illusory transparency and colour mixing.

— 43 katametry, similarity transformation of axis systems.

[Schema drawing]

around a central point, dots arranged at distances 1 2 3 4 are themselves starting points for the configuration of katametric figures, which from these points likewise have the distances 1 2 3 4 on the new axes. the connection consists of the common circumcircle.

5

PRECISION – IMPRECISE

— 51 symmetry: katametric figures, created by turning a ray over a parallelogram.

— 53 [Schema drawing]: diameter 4 5 6 7 cm A3 format, developed from a square and its dialogues. Katametry

6

61 TO 64

exercises after ames demonstration

depth graduation through colour treatment of planes

7

71 TO 75

harmonisation of planes through colour and structural changes

8

— 81 composition of 5-10 circle segments in a system of 20 circles

— 82 arrangement of 3 accents in each of 2 planes 20/20 each with 36 elements

— 83 3 overlapping systems 3 accents from each system form together a group by way of mutual colour

(*1965 in Meßkirch, Germany) has been head of the HfG Archive since 2013. He studied art history and modern German literature in Tübingen, Newcastle (GB) and Hamburg from 1984. In 1999, he completed his doctorate at the University of Tübingen. He is involved in numerous exhibition and publication projects. Since 2003, he has repeatedly taught design history at the universities of Ulm, Würzburg, Schwäbisch Gmünd and Biberach.