Totems of Social Design: A New Politics of Material Culture

Industrial design differs from its sister arts of architecture and engineering in one basic way: it is the only profession that has moved from discovery to degeneracy in one generation. Members of the profession have lost integrity and responsibility and become purveyors of trivia, the tawdry and the shoddy, the inventors of toys for adults.

– Victor J. Papanek (1971)

In the early 1970s, a ground-breaking book, provocatively titled ”Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change”, emerged as a totem for a radical new genre of socially responsible design. Condensing within its pages an ersatz manifesto for an era facing the onset of post-industrial upheaval and environmental disaster, its prophetic warning ‘that industrial design, as we have come to know it, should cease to exist’ holds even greater resonance today, in a world of unbridled disposability. Flanked on the activist-designer’s bookshelf by Rachel Carson’s warning of imminent ecological disaster, Silent Spring (1962), and Teresa Hayter’s critique of the mechanisms of neo-colonialism, Aid as Imperialism (1971), it propelled its author, designer and critic Victor Papanek, to the apex of his career as the late twentieth century’s agent provocateur of design.

As one of the most widely read and influential design books, translated into over 20 languages and never having fallen out of print since its inception, Design for the Real World converted a generation through its clarion call to embrace a fresh politics of design. Its legacy continues today, manifest in areas ranging from design anthropology, the maker movement, critical and inclusive design and beyond. Pre-empting the 21st century shift towards design as a dispersed transdisciplinary phenomenon, the polemic provoked uprisings within design schools through its critique of design’s unspoken role in bolstering social inequality, ableism and discrimination by engendering cultural homogeneity with a ‘one-size-fits-all’ mentality. Instead, it proposed a humane design approach imbued with anthropological sensitivity to the local, the vernacular, and an understanding of the broader cultural nuances of design’s power in undermining or solidifying social inclusion. In challenging design’s assumed role as the originator of an ever-expanding field of products in an age of over-abundance, its overarching message was that design had the potential to be the key agent of social change, rather than a tool for stylization, aestheticization, or a driver for increased consumption. Ultimately, it advocated for a holistic model in which design is understood as inseparable from the social relations, customs, rituals and histories in which they are embedded.

Drawing on the cutting-edge social projects of students and previously little-known designers, its influence spanned North America, Europe, the Soviet Union, and the Global South. It prompted a revolution in design pedagogy by introducing a distinctly anthropological method into design practice that challenged the rational market logic of capitalism as the driver of innovation. At the forefront of its approach was the idea that users themselves should lie at the core of a radically new design practice that favoured vernacular and indigenous solutions rather than the technocratic ideologies of modernism. Despite being over a half-century old, it remains widely read in design schools across the world as a manifesto for change.

In 1973, the Italian edition of Papanek’s polemic was released under the title ”Progettare per il mondo reale: il design: come è e come potrebbe essere” (Designing for the real world: how it is and how it could be). In January that same year, the seminal design magazine Casabella launched the radical open-ended pedagogic experiment Global Tools featuring leading figures of Italian radical design and architecture, from Archizoom Associati, Riccardo Dalisi, Gaetano Pesce, Ugo La Pietra, Ettore Sottsass through to Superstudio and U.F.O. The group espoused an exploratory, multi-disciplinary didactic series of workshops premised on generating an alternative culture of design, untethered from the legacy of Fordist industrial relations and conformist design school traditions. Just as Papanek’s book lambasted the failure of contemporary design education for its emphasis on profits and ‘clients’ rather than an engagement with social needs, the Global Tools initiative revolved around a multi-sited ‘anti-school’ for design. Makers would be re-enchanted through engagement with pre-industrial craft-based genres, the sensorial process of design becoming a political strategy within itself.

Most importantly, Design for the Real World and Global Tools shared an agenda to reaffirm the social purpose of design beyond the rubric of modernism, offering fervent critiques of late industrial society’s role in fostering widespread alienation and the destruction of local resources, indigenous knowledge, cultures and skills. While Papanek’s examples of autochthon were mainly found in ‘developing’ countries and communities (including Greenland and Indonesia with Bali in particular), members of the Global Tools collective turned to the eroding peasant cultures of Italy, and more specifically Tuscany. Both Papanek and the radical Italian collective advocated multi-disciplinary, experimental and non-hierarchical models of pedagogy and the dismantling of contemporary design conventions in favour of alternative economics of value. Using rhetoric that strikes a chord with designers in the late 21st century, they envisaged a devolved ‘maker culture’ rising from the ashes of the post-industrial, crisis-ridden late capitalism, that would empower localised groups, individuals and society. Original Global Tools member Franco Raggi described the project thus: ‘As opposed to the established and accepted practice of technological, comfortable, useful and functional design, the intent is to posit a nomadic practice for an archaic, dysfunctional design.’[1] Anthropologically inspired ideas around material culture and ritual meaning, and an emphasis on users and co-design, underpinned their newly forged design philosophies.

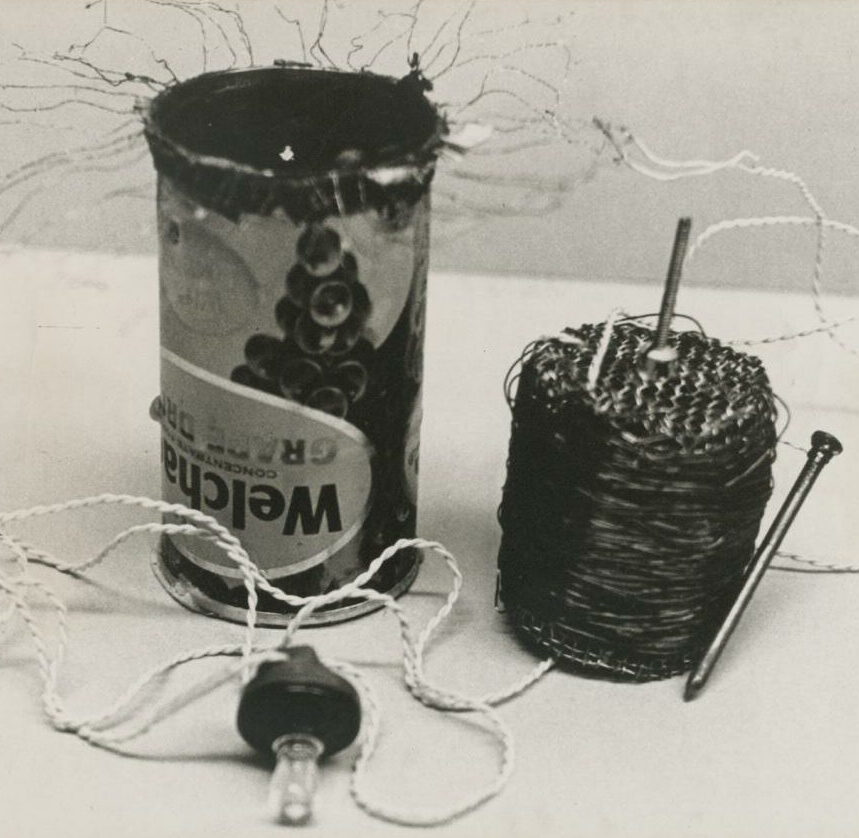

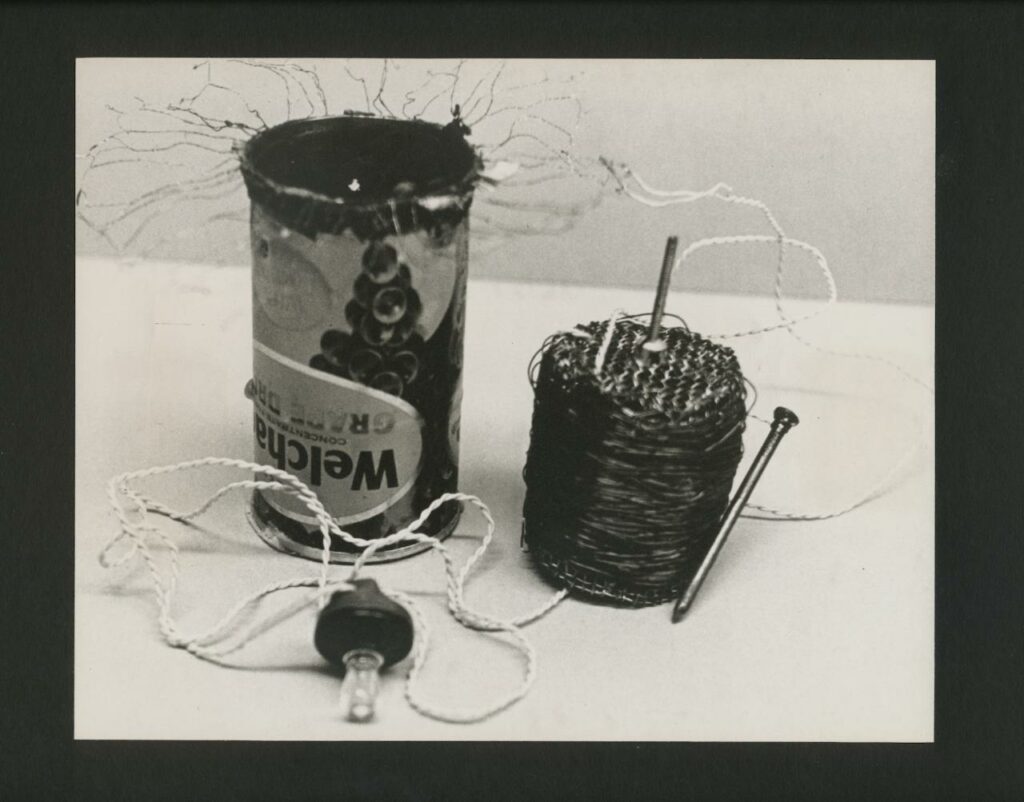

One high-profile prototype that emerged from this new politics of design exemplified the contradictions of a movement that aimed to apply design to socially meaningful purposes, while seeking to distance itself from neo-colonial intervention. The battery-free Tin Can Radio (designed by Victor Papanek and his student George Seeger for UNESCO) was powered with dried animal dung and constructed from waste components, intended for distribution among non-literate and isolated communities. Its image featured prominently on the dust jacket of the first edition of Design for the Real World, with the words of endorsement by Finnish designer Barbro Kulvik-Siltavuori pre-empting the criticism the design would come to provoke: ‘Today there is much controversy about design responsibility. Some think [Papanek] is too political, others that he is not political enough; some that he encourages neo-colonial exploitation, others that he is selling out the white race.’

While the radical Italian designers shared a similar set of objectives with the ‘real world’ agenda of socially responsible design, the release of the Italian edition of Design for the Real World also unleashed a fierce attack on its entire premise. In the pages of Casabella, the highly regarded Italian design journal (mouthpiece of the Global Tools initiators), leading design theorist Gui Bonsiepe (alumnus of the Ulm School of Design) berated Papanek for his naïve and neo-colonial approach to socially responsible design. Bonsiepe condemned the social designers’ attempts to address inequality through design as a ‘pale crusade of the petit bourgeois’, criticizing the fact ‘that no mention is ever made of the organization of relationships of production and the role of productive forces, especially that of the working class’. Referring to the much-fêted Tin Can Radio design for the ‘Third World’, the excoriating review implicated its designer in a broader conspiracy, that of working covertly for the US military: ‘The radio constitutes a tool of ideological penetration and control, and what drove the development of the project has now been transformed into nothing less than a tool of UNESCO pageantry.’ Bonsiepe hammered the last nail in the coffin of Papanek’s radical and socially responsible design profile with the pointed comment that: ‘Maybe the author, during his stay in the USA and his attacks against the design ‘establishment’ thought he could find allies in military circles, a tactical, strategically disastrous error.’

The social design experiments and initiatives of the early 1970s, conceived outside the indices of purely commercial motives, were riddled with contradictions, many of which could be said to pertain to contemporary socially responsible design today.

And yet multiple aspects of that original social design agenda remain pertinent: the exploration of indigenized design, the critical appraisal of the role designers play in accelerating (and remedying) global climate change, and the pressing question of what form design’s socio-environmental accountability might take. Moreover, design remains, as was claimed in the heyday of radical politics, a force as likely to inflict harm as to remedy it. Tasked with shaping our material and immaterial existence, should designers be held answerable to broader humanitarian goals, or merely to the whims of their techno-ideological paymasters? Just how far does their responsibility extend to the long-term outcomes of their work, be it a driverless vehicle or a disposable diaper? Although the global application of much of today’s social design is debatable, without the new political agenda of the early 1970s, design would have remained a non-critical, rationalized, problem solving and homogenous practice – one that served only minority interests.

is professor of Design History and Theory and Director of the Papanek Foundation at the University of Applied Arts Vienna. A trained social anthropologist (University College London) and design historian (V&A/Royal College of Art, London), Clarke lectures internationally and is author of numerous publications considering the politics of design and material culture. Her most recent monograph, Victor Papanek: Designer for the Real World (MIT Press 2021) considers the controversial history of the social design movement.