“We’re all in this big conversation” – Design as Plurivocality

Dear Lesley-Ann, I was always planning to start this discussion by quoting the legendary designer and DJ Virgil Abloh, who imagined design pedagogy and practice as inherently plurivocal. He thought of everyone as being in one big conversation. Scrolling through articles on The Guardian app this morning, though, I serendipitously stumbled across an article by Zadie Smith on the rerelease of Gretchen Gerzina’s milestone history Black England: A Forgotten Georgian History, for which Smith has written the foreword.

As Smith, a well-known novelist, essayist and professor of creative writing, points out, Gerzina’s milestone book highlights and redresses the erasure of Black people and their achievements from British history. When she first read the study back in the 1990s, it profoundly influenced her self-understanding and development as a writer.

If I was half asleep when I started reading the article this morning, I was certainly wide awake by the end – because the content resonated so strongly with the tenets of many of your projects and the questions I wanted to discuss with you.

Indeed, the article drives home the point that you and your colleagues so pertinently make in The Black Experience in Design: Identity, Expression and Reflection (2022), namely that white cultural supremacy in education brings forth impoverished, skewed narratives that distort history and ultimately stifle creativity. It shuts down the “big conversation’ that Abloh was speaking of, or at least prevents it from flourishing.

How did The Black Experience in Design, a project that seeks to both revise and re-envision the past, present and future of design education, come about?

I am one of six editors of The Black Experience in Design. The other editors are Anne H. Berry, Kelly Walters, Jennifer Rittner, Kareem Collie and Penny Acayo Laker. The project was Anne H. Berry’s brainchild. I think Kareem called me and asked me if I’d be interested in joining. When we all met, we brainstormed about how to respond as design educators to the interest in Blackness in design. Anne and a few of the others were interested in writing the book that they yearned for when they were design students. I was tired of questions like “where were all of the black designers?’ and excited to create a space where we could challenge those types of questions and show that Black designers are here, can tell their own stories, and are doing exceptional work. Personally, I found the question very White-centric. There are Black people doing design work, but I felt that the people who were asking the question were being lazy, and not looking in the right places. We talked about several different formats. We seriously considered a special issue of an academic journal, but we quickly recognised there were too many people we wanted to invite to contribute, and a journal would only accommodate six to eight essays, so the idea morphed into a book. One of the editors knew Steven Heller, who was generous enough to meet with us and talk through the idea. We created a few lists of people we’d want to be represented within a ‘textbook’ about Black design, and we considered several different formats. We had some guiding principles about representing a range of disciplines within design, a range of identities, the authentic voices of the contributors, and about creating many different means of being a contributor, from poetry to essays, from images to conversations and more.

Throughout your academic career you have worked extensively to broaden conversations around design practices and histories, to include multiple voices and perspectives coming from outside ‘dominant’ design culture. Here I’m thinking in particular of your experience as convenor of the Design Research Society’s Pluriversal Design Special Interest Group (PluriSIG). To what extent did your prior research flow into – and perhaps prepare you for the outcomes of – The Black Experience in Design?

My previous research and the work with the Pluriversal Design Special Interest Group had a huge impact on my process within this project. When I started, I was a Professor of Practice at Tulane University in New Orleans, and we had worked for two years on the podcast Hello from the Pluriverse, which featured student interviews with designers around the world. That podcast was tied to one of PluriSIG’s aims of shining a light on the wide diversity of design practices around the world. The Black Experience in Design was also published after the Pivot 2020 conference, a conference in which we had many conversations about shifting centres, methods, epistemologies and ontologies in design. What I/we learned from the podcast and the conference were strategies for supporting people as they told their own stories and ensuring that these stories were accessible in traditional academic formats. In both projects we created many different ways of participating, such as conducting and recording interviews and then downloading and publishing transcripts or transforming them into essays. So, by the time I joined The Black Experience in Design team, I knew that we could move beyond traditional academic publication barriers to make sure we had the participation of many voices in the work. I’d say that my previous work prepared me for the process, more than the outcomes. I used strategies that I learned from previous research in my role as editor and led writing groups for contributors, provided writing prompts, did interviews with those who didn’t have the time to write, ghostwrote articles based on interviews, etc. I’d say that is, in part, why we were so successful in collecting so many stories. There were so many ways to contribute to this work.

My research and the corresponding research methods often focus on emancipation and liberation. I’m very satisfied with the outcome of the work, because this is a book about Black creatives by Black creatives in which close to seventy Black designers tell their own stories. It’s a ‘for us, by us’ emancipatory and liberating work. I’m very proud of having played a role in making this possible.

Were there voices in the anthology that surprised you?

There are so many stories in this work that it’s hard to single out what might have surprised me. The voices in the anthology provoked a range of emotions for me. So, I suppose that ‘surprised’ might be a word I’d use, but I also felt seen and validated by the familiarity of themes in some of the stories. The Ghanaian-South African professor Nii Commey Botchway made me reflect on what Blackness is and what design is. Steve Jones’s essay speaks directly to the experience of many Black design students at a predominantly White institution, where a professor gives a sometimes unintentionally exclusionary assignment prompt. Kaleena Sales shares reflections on what it means to be a Black design educator teaching mainly Black students at a historically Black university. It is not a privilege that many Black design educators have in countries where they are part of a minority group. The way in which she has wrestled with the way she used to teach them to fit into a White world was very poignant. I really enjoyed Lauren Williams’ manifesto for Black women in academia, maybe it hit too close to home! I was privileged to have a seventeen-minute conversation with adrienne maree brown that led to her contribution. She gives great advice for Black designers, to listen for design within themselves, to think about abolition, to read Audre Lorde! I love the ending of her piece: ‘Have a really massive vision! Because I do think that this is our time.’ If I had to recommend that people read one essay, I’d say read brown’s because it is so hopeful, but it’s hard to recommend only one.

In the book, Maurice Cherry – creator, producer and host of the groundbreaking podcast series on Black designers, Revision Path – contends that ‘merely celebrating yourself as a Black designer is an act of rebellion’. Such ‘rebellion’ is crucial if design education is to become truly social. Yet the scope of the book extends well beyond the celebration of Black designers and histories of resistance. Indeed, it simultaneously explores innovative methods and models for design teaching and research. And it reimagines learning institutions as non-hostile, liberatory spaces. What kind of historical approaches do such new methods build upon?

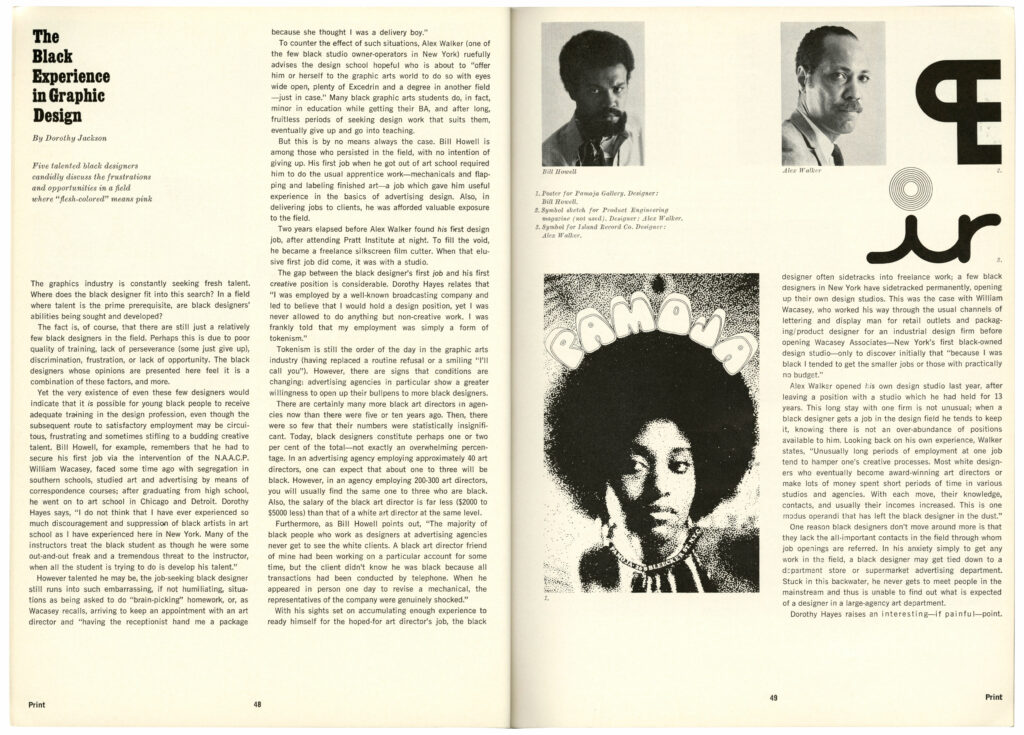

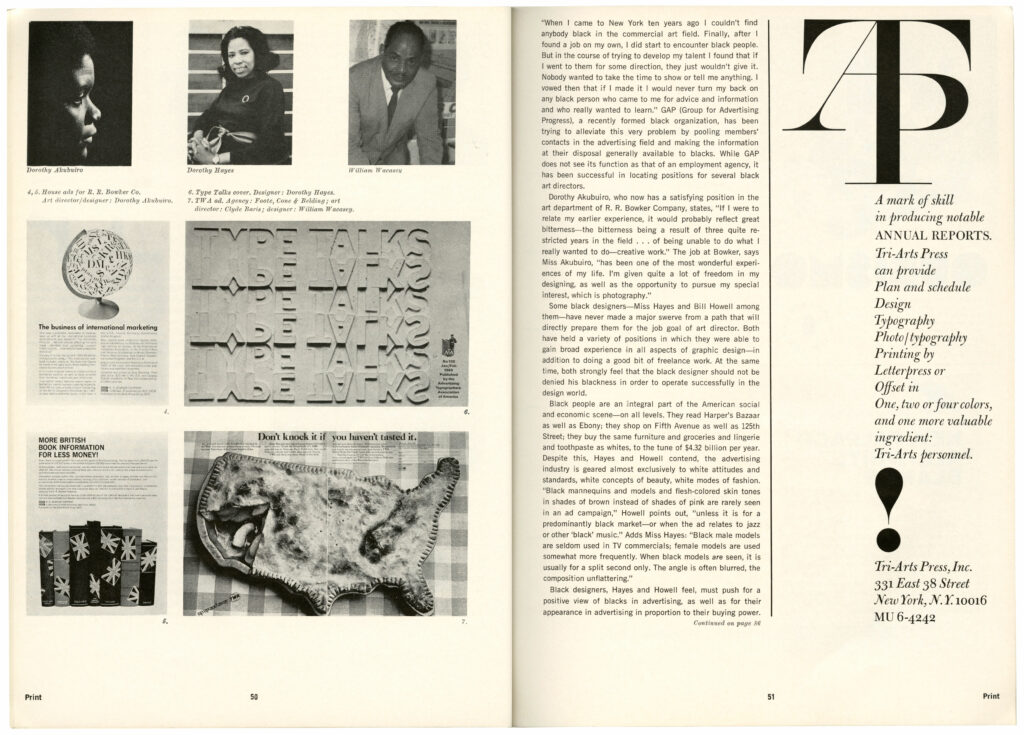

This is a difficult question. There are some authors who lean more intentionally into history in their work, such as David Pilgrim, who uses historical objects to teach social justice. Colette Gaiter tells her story using images from the past, especially the 1960s and ’70s. Alicia Ajayi writes about the design of ‘free papers’ which were artefacts that guaranteed the free passage of the formerly enslaved.

The history of the discipline can seem exclusionary for many Black designers. The new methods that these designers and educators propose do not necessarily have to build on historical approaches (if I’m understanding the question correctly). The ones with formal design training may be instinctively building on their training, but might also be reacting and rejecting it, because they have been able to see gaps in the historical approaches of design. As outsiders or people who are othered, these designers and educators can see keenly what is needed for them to thrive and then propose methods that fill those gaps.

Some of the new methods are proposed by people who do not have formal design training, but who operate within the world of design. They are drawing from their lived experiences, approaches from other disciplines, their social experiences of community, collaboration, inquiry and more. Chris Rudd shares a syllabus from his class. In his essays he talks of complicating Bauhausian traditions by weaving in indigenous practices. His reading list includes texts on race, class, feminism, and politics, and he is advocating for a more critical perspective in design.

Speculative narratives, whether historical or futuristic, also play an important role in evolving emancipatory educational spaces …

I edited the section specifically about futurism, but I do believe that a conviction that we deserve better and that we can make better for ourselves (nobody else has to save us) drives the development of emancipatory new approaches and new spaces. Something that really bothered me in 2020 was the way the questions about ‘where are the Black designers and how can we help them’ were asked. What I loved about the accounts in Chapter 8 are the stories of defiance and agency. They are inspiring stories of how people started their own spaces, such as Maurice Cherry’s Revision Path podcast, Moline’s Facebook group and Web platform for African American Graphic Design and Malene Barnett’s Black Artists and Designers Guild. Some of the essays in the futurism section could just have easily been placed in the radical and liberatory spaces because the contributors like Lonny Brooks, Woodrow Winchester III, Adah Parris and John Jennings are in fact using futurism to evolve their work, and for themselves and others to imagine new spaces and practices.

One concrete product of your research has been the Designer’s Critical Alphabet, a deck of cards and a digital app you created in 2019. You have described the cards as a tool to help train design students, educators, researchers and practitioners to sharpen their critical awareness of design histories, pedagogies and practices, to reflect on diversity, inclusion.

Could you please tell us a little bit about the project and the ways in which the contemporary world as a whole might benefit from unlearning exclusive epistemologies and methodologies? What do human and more-than-human beings stand to gain from pedagogies at once plurivocal and pluriversal?

Oh my, you ask difficult questions. The aim of the Designer’s Critical Alphabet, and the follow-up Good Vibes Deck is to encourage people to ask more questions. I say all the time ‘Question everything! Nothing is sacred!’ So, these tools have introductory critical questions. The idea is not that these are the only critical questions that people must ask, but that the deck can encourage people to remember to ask and reflect on questions about race, gender, language, politics, and even to reflect on their own positionalities and self-awareness in the work that they do as designers. Hopefully, where there may be pressure to flatten and simplify, the alphabets will encourage people to complicate, sit with the discomfort that complexity can bring and use this to gain a deeper understanding of the problem area that they may be focusing on. What do we all stand to gain from pluriversal pedagogies? On a ‘feel-good’ level we all gain from being able to learn from the richness of the many different perspectives that people bring to issues. The mere knowledge that our position is not the only position and may not be the right position leads us to ask questions in different ways with more openness and humility. On a more practical level, perhaps this humility can lead to greater collaboration across differences.

is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Design Studies at North Carolina State University. She has a BA in Industrial Design from the Universidade Federal do Paraná in Curitiba, Brazil. She has a Master’s degree in Business Administration from the University of the West Indies in Trinidad and Tobago. She earned her Ph.D. in Design from North Carolina State University in 2018. She is co-Chair of the Pluriversal Design Special Interest Group of the Design Research Society. Before joining North Carolina State University, she was the Associate Director of Design Thinking for Social Impact at Tulane University in New Orleans and a lecturer at Stanford University and the University of the West Indies.

In her research, she promotes greater critical awareness among designers and design students by introducing critical theory concepts and vocabulary into the design studio, for example using The Designer’s Critical Alphabet and the Positionality Wheel. She is one of the editors of The Black Experience in Design, an anthology featuring the stories of 70 Black designers, and is currently completing a book on design for social change.