Words and Worlds – The poetry of design between Brazil and Germany

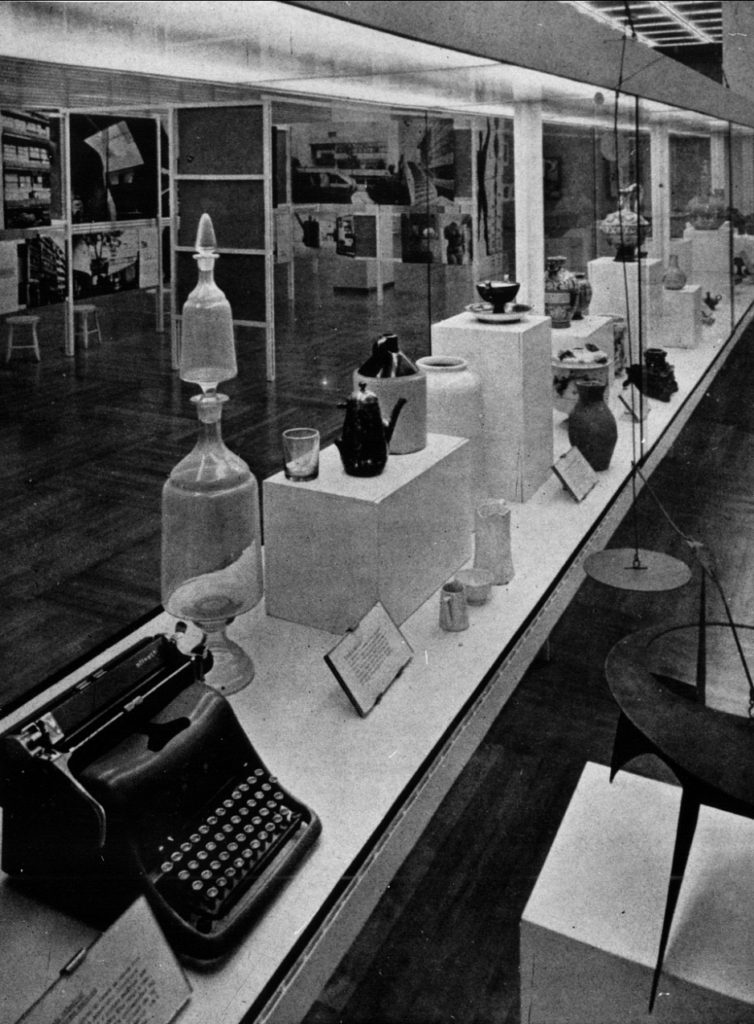

In the 1950s and 1960s, as a result of an intense dialogue between Brazil and Germany in the fields of architecture, art, poetry, design, and theory, a common production emerged. Educational institutions, such as the Instituto de Arte Contemporânea do Museu de Arte de São Paulo (IAC-Masp, Institute of Contemporary Art of the Museu of Art São Paulo, 1951), the Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm (HfG Ulm, Ulm School of Design, 1953), and the Escola Superior de Desenho Industrial, Rio de Janeiro (ESDI, School of Industrial Design, 1962) and their well-known relations were fundamental for this production, generating the beginning of an extensive web of associations that would advance beyond their walls.

The first contacts took place mainly through São Paulo Biennials, the São Paulo Museum of Art (Masp) exhibitions and its Institute of Contemporary Art (IAC), considered to be the first design school in Brazil. In 1953, coinciding with the inauguration of the HfG Ulm, Max Bill participated in the jury of the second São Paulo Biennial[1] and connected Brazilian artists with Ulm and its ideals. From 1953 to 1956, six Brazilian artists and designers, among them Almir Mavigner, Mary Vieira, Alexandre Wollner and Yedda Pitanguy,[2] studied at the HfG Ulm, becoming pivotal in several connections that would unfold between the two countries.

Meanwhile, during the 1950s, discussions involving Max Bill were held about the possibility of creating a design school at the Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro (Mam-RJ, Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro), for which Tomás Maldonado was assigned to write a curriculum proposal. Although the Escola Técnica de Criação (ETC, Technical School of Design) never came into being, courses and lectures did take place at Mam-RJ, including a visual communication course co-taught by Maldonado and Otl Aicher.

In the early 1960s, the ESDI was founded in Rio de Janeiro, and its first curriculum referred to Maldonado’s plan for the ETC-Mam school and adopted the scientific approach that was prevailing in Ulm. Alexandre Wollner and Karl Heinz Bergmiller, former Ulm students, were among its founders. The German theoretician and HfG professor Max Bense taught several courses at ESDI, where the concrete poet Décio Pignatari also worked as a professor of information theory.

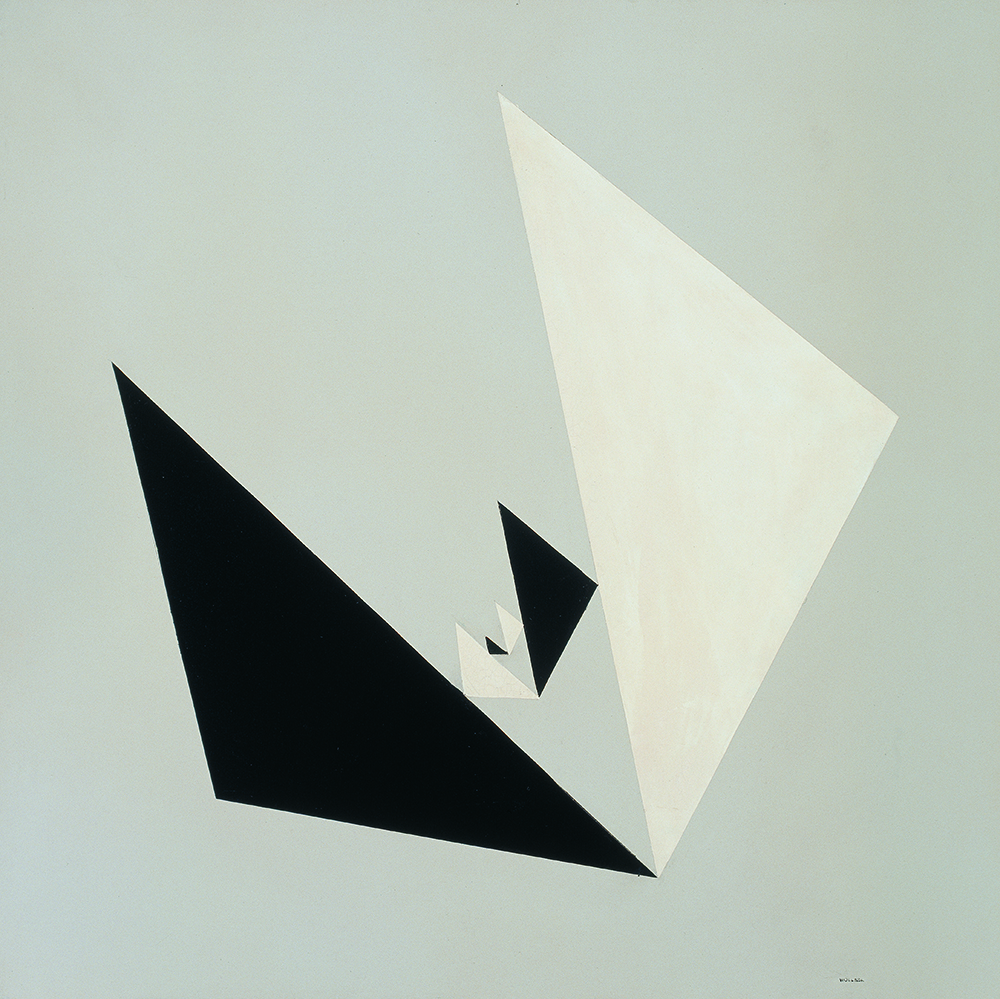

In these exchanges one can follow a constant concern with the investigation of non-discursive languages for which concrete art marks a fundamental moment. At the same time it appears as a first point of intersection between Brazilian and German artists during the 1950s. Based on a self-referential vocabulary of a purely plastic materiality (lines, planes, and colors), concrete art ceased to be a representation of reality outside the canvas and became the presentation of its own structural instrumentation. For its exponents, the essential aspects of visual art were matter, space-time, and movement. Art was considered a form of knowledge, and the artwork an autonomous object. The movement defended a universal art that through the search for a collective meaning and the collaboration with industry and the mass media would reach the sphere of the everyday, unifying art and life. Thus, design played a fundamental and inseparable role in this concept of art.

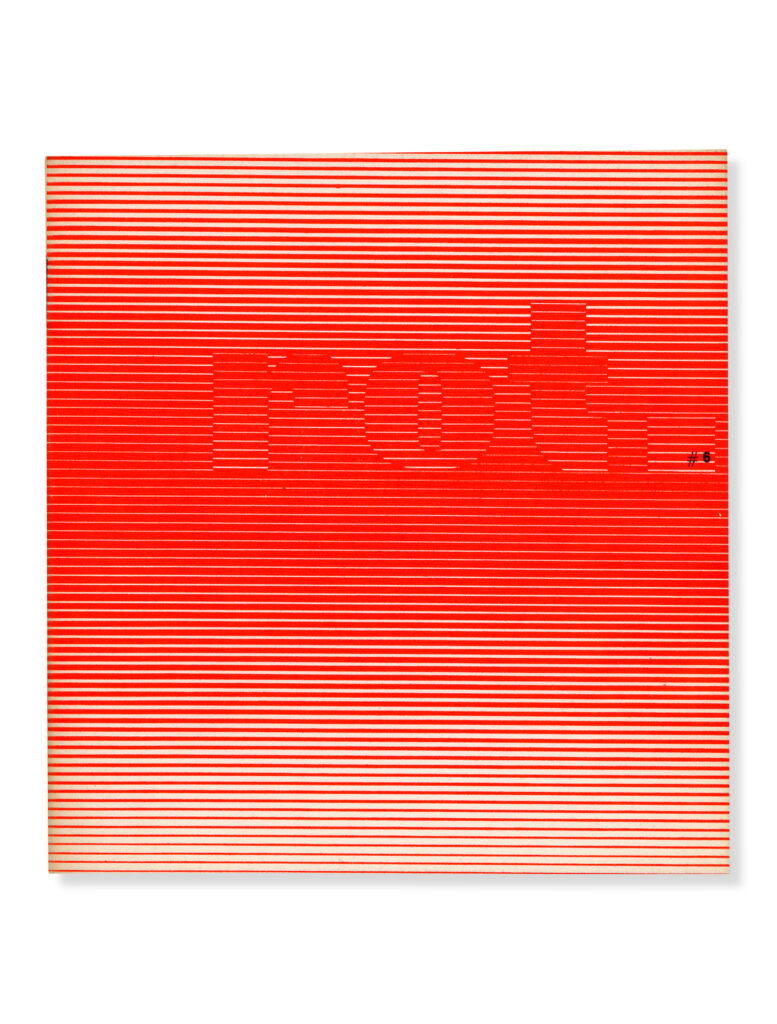

As in the field of concrete art and design, concrete poetry was based on the resumption of a constructive corpus that revolved around the European avant-garde, mainly the De Stijl movement and the Bauhaus school,[3] establishing tight relationships with contemporary experimentation in other fields such as music, painting, architecture, and design. This tradition finds expression in poets’ productions through the incorporation of a structural and materialist line of thought and the defense of the use of mass communication.

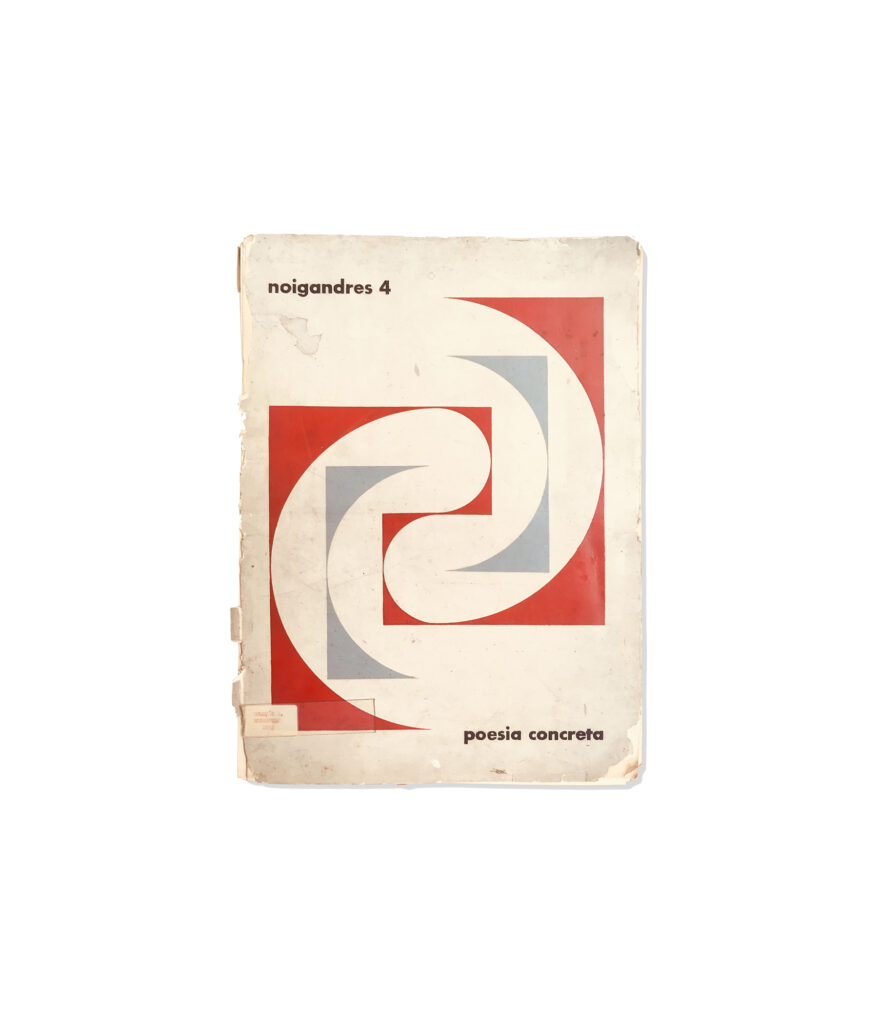

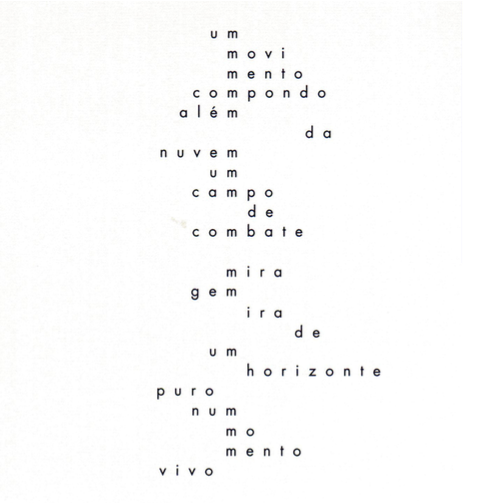

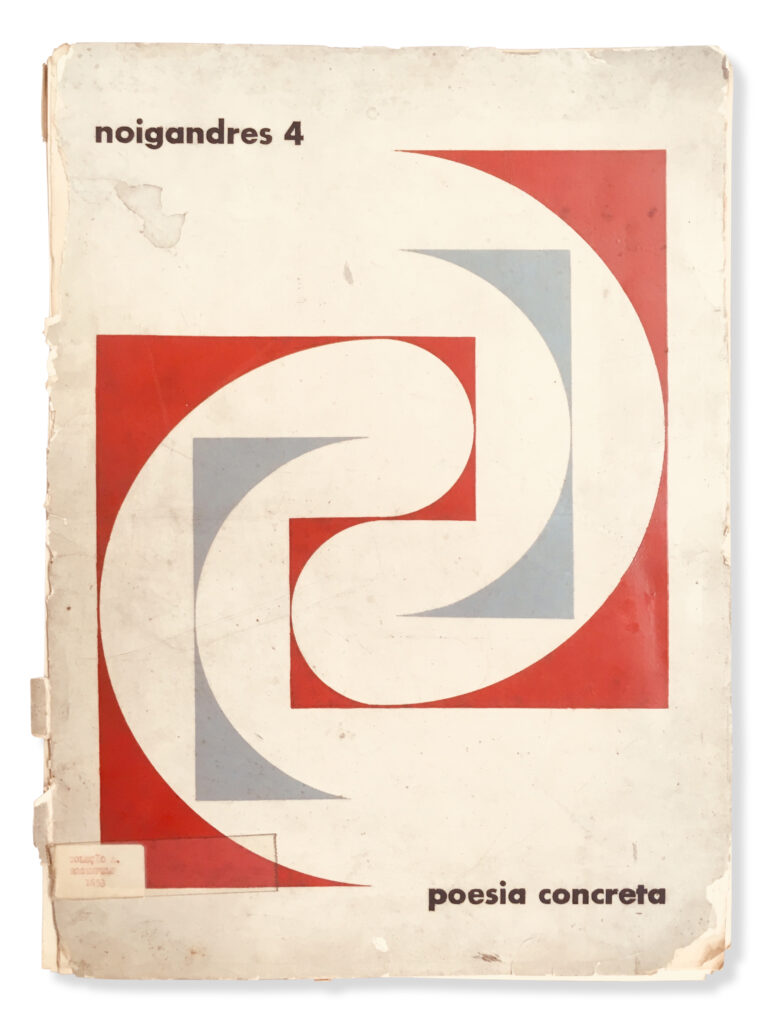

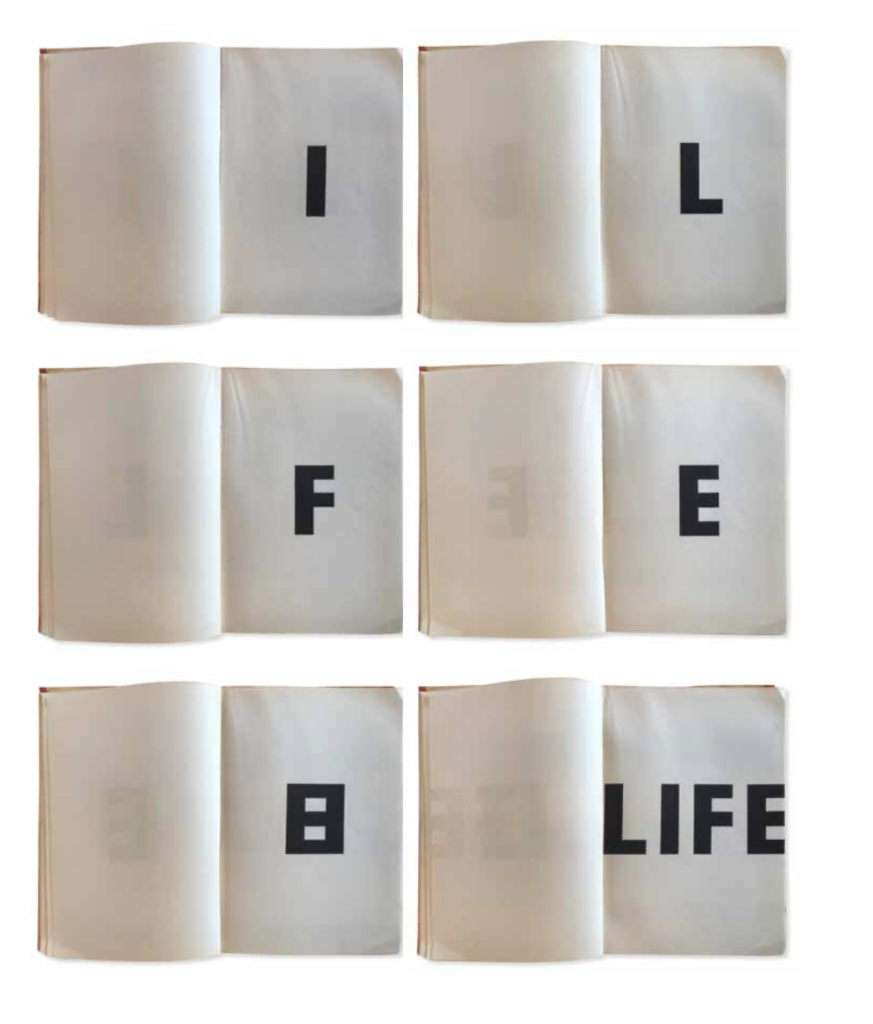

In 1952 in Brazil, Décio Pignatari and the brothers Augusto and Haroldo de Campos created the group Noigandres,[4] decreeing an end to the historical cycle of the verse and exploring the concrete graphical space of the page as a poetic practice.

In 1953, during a visit to the Brazilian students at the HfG Ulm, Décio Pignatari met the Bolivian-Swiss poet Eugen Gomringer, Max Bill’s assistant at the time. For Gomringer and the Brazilian poets, poetry was to be constituted by the simplest structure based on the relationships between words rather than their discursive juxtaposition, with the former being called “constellation”[5] and the latter “ideogram.”[6]

The word in its three dimensions – spatial-graphic, acoustical/oral and semantic – was considered as an autonomous “thing-word” and poetry turned into a “verbivocovisual”[7] system, defined as a specific linguistic area that used the advantages of the simultaneity of verbal and nonverbal communication.

Moreover, the thing-word was seen as a living organism or a living system – “the concrete poet sees the word itself … as a dynamic object, a living cell, a complete organism, with psycho-physical-chemical properties, tactile antennae of circulation heart: alive.”[8]

The cooperation between Décio Pignatari and Eugen Gomringer unfolded in several ways. One of these was the encounter between the Brazilian concrete poets and HfG Ulm professor Max Bense who together with his colleague, the semiotician and publisher Elisabeth Walther[9] would organize several exhibitions and publications about Brazilian poetry, art, and design in Stuttgart, besides writing a philosophical travel report, “Brasilianische Intelligenz: Eine cartesianische Reflexion”, as a result of his close interactions and five visits to Brazil.[10]

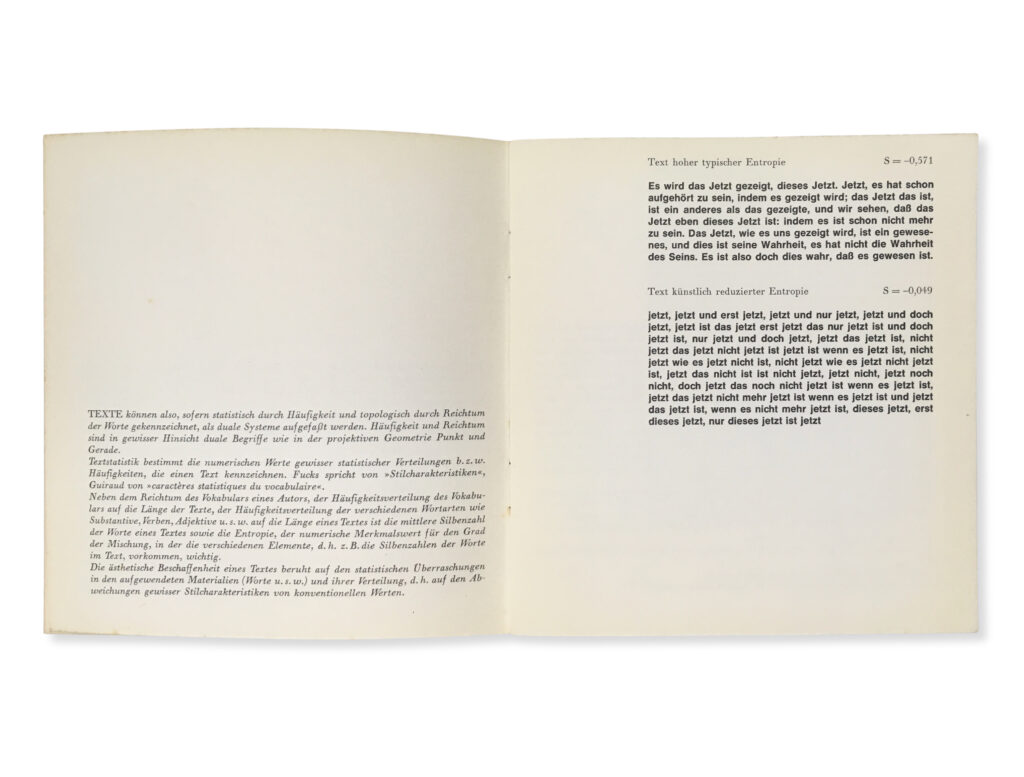

Bense, whose work focused on the relationship between aesthetics and technology, developed a rational aesthetic defining the components of the text, be it utilitarian or literary, as a repertoire of statistical language built according to information measurements as opposed to semantics.

An approximation between Bense’s design theory and those of the Brazilian concrete poets becomes clear in the procedures proposed by the former in the experimental curriculum for HfG Ulm’s information department:

- “Conversion of natural languages and artificial languages into precise languages.

- Experiments on grid systems, shortening techniques and montage techniques.

- Concentration and dispersion of form and topics.

- Syntactic and semantic shortening, compression, distortion, lengthening, alienation.

- Accidental and attributive descriptions, phenomenological reduction and deflation of meaning.”[11]

For Bense the word should not be used as a carrier of intentional meaning but as an element of material design, so that meaning and design (Gestaltung) are mutually conditioned and expressed.[12] Likewise, for Brazilian concrete poets the word was a purely objective thing, free from redundancies and inaccuracies, with the poem perceived as an experimental search for clarity and integrity in language. Poets strove to create an economic structure, analogous to the speed of modern communication and technology, prefiguring the poem’s reintegration into everyday life – similar to how the Bauhaus approached the visual arts – either as a vehicle for commercial advertising or an object of pure enjoyment. In either case, the aim was to approach the word, in an elementary sense, as if it were being heard for the first time.

In search of a non-discursive language, poetry revealed the capacity of language-as-design:

“Our century is the century of planning, of design and designers: industrial design and architecture are studied and projected as messages and as languages; writers, poets, journalists, advertisers, musicians, photographers, filmmakers, radio and television producers, painters and sculptors are beginning to become aware of designers, forgers of new languages.”[13]

is a Brazilian researcher and graphic designer currently based in Berlin. She holds a MSc in Architecture and Urbanism from the São Paulo University (FAU-USP) and a MSc in Design Research from the Anhalt School of Applied Arts and the Humboldt Universität zu Berlin in cooperation with the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation. Her most recent research revolves around the entanglements between Brazilian and German post-war modern movements in art, design and architecture, questioning the flow between center and periphery.