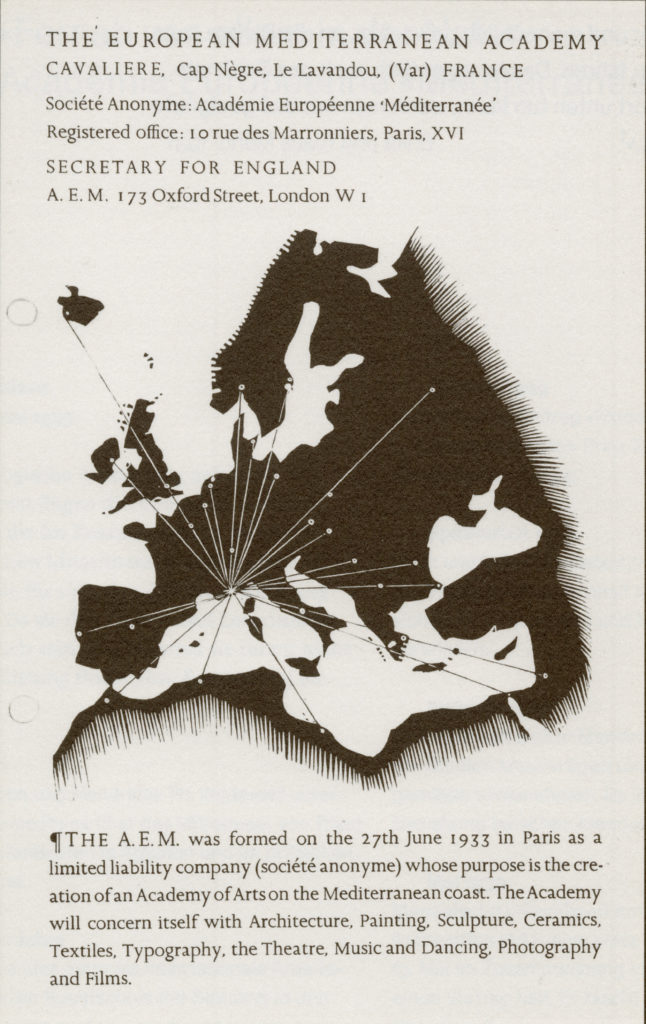

In the early 1930s, the publicist and artist Hendricus Theodorus Wijdeveld from Amsterdam and the architect Erich Mendelsohn from Berlin planned to open a European art school on the French Riviera. Even though the adverse political circumstances of the time meant that teaching never began, the ambitious project had progressed to such a degree that the academy’s concept and aspirations were already clearly formulated. The financing was secured through shareholders and a large plot was bought in Cavalière, between Le Lavandou and Saint-Tropez.

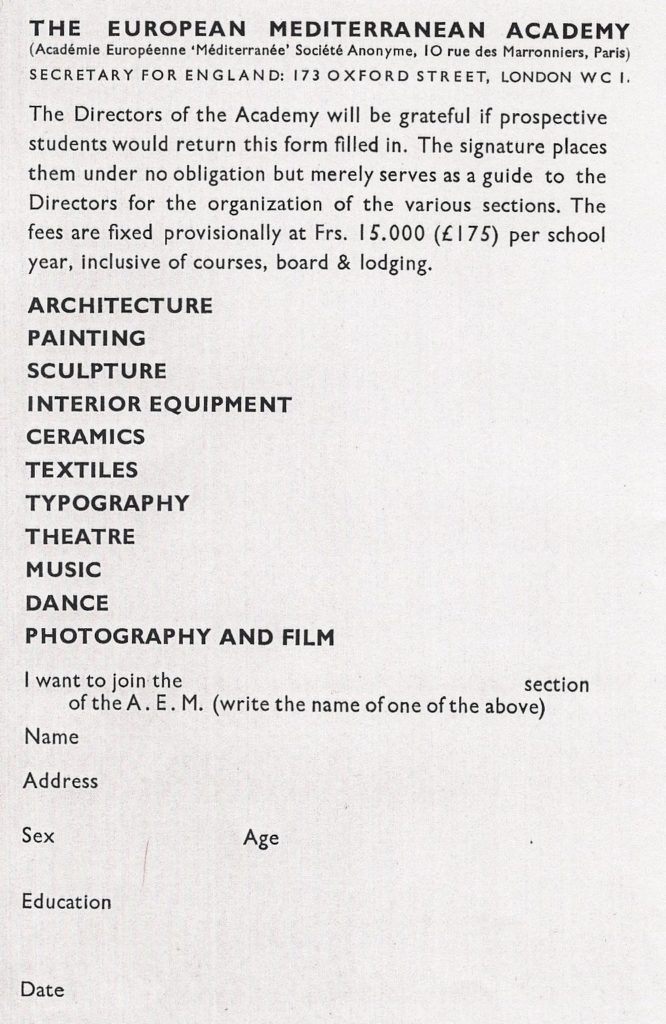

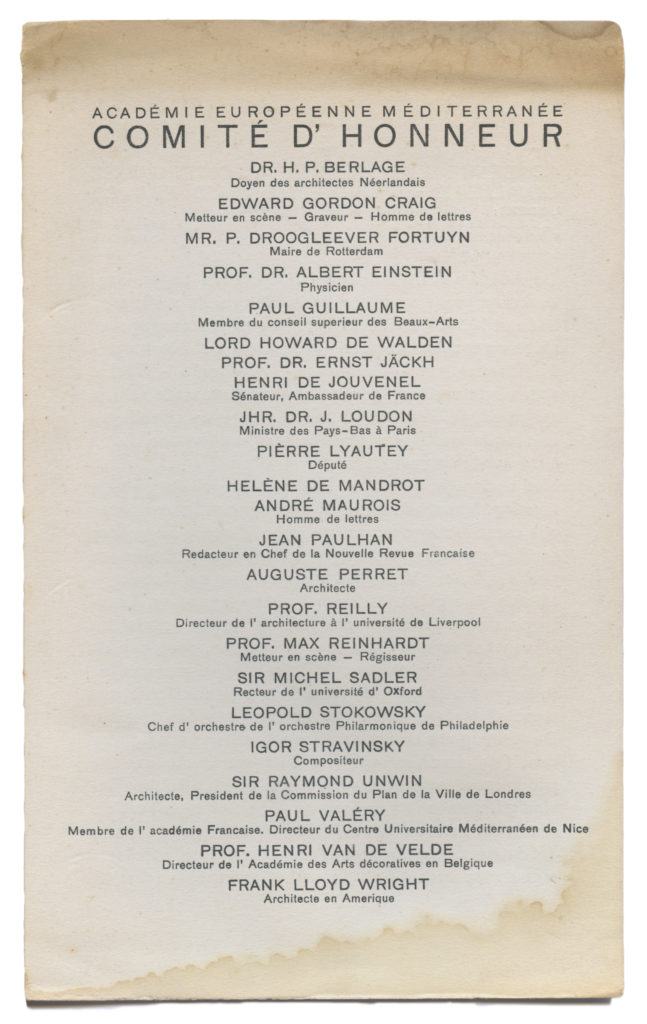

Brochures outlining the organisational roadmap and curriculum were printed up in five languages and plans drawn up for studios, offices and accommodation units. Artists from various European countries were recruited as teachers, among them the British sculptor and typographer Eric Gill, the German composer Paul Hindemith and the Spanish sculptor Pablo Gargallo. The curriculum was set out along multidisciplinary lines: In addition to the triad of painting, sculpture and architecture, there were departments for interior design, stagecraft, typography, ceramics and textile design as well as postgraduate courses in music, dance, photography and film. A comité d’honneur comprising important personalities from science, art and politics such as Albert Einstein, architects Hendrik Petrus Berlage, Auguste Perret and Henry van de Velde, art collector and patron of the arts Hélène de Mandrot and writer Paul Valéry lent the project the required intellectual rigour and embedded it in a network with multiplier effects.

The inspiration for the project came without doubt from the Bauhaus, whose concept and genesis were familiar to both initiators. But Wijdeveld and Mendelsohn were keen to do more than merely transfer the progressive German art school to the sunny South. Naming their artistic educational institution the Académie Européenne Méditerranée (AEM) was programmatic. This knowingly set it apart from the workshop ideal of its reference object, alluded to the European body of thought and drew on the classical heritage of the Mediterranean region to forge its identity. The involvement of the painter Amédée Ozenfant as the third director activated finer points of French modernism such as purisme and retour à l’ordre, which are located in the literary and historic-philosophical context of la pensée de midi and longue durée.