The Academy of Applied Arts in Zagreb, founded in 1949, is a shining example of a post-war educational model built on the legacy of the Bauhaus, which places it among a large number of educational institutions that emerged worldwide after 1933. The establishment and operation of the Academy must be viewed in the context of time, of the new political atmosphere of socialist Yugoslavia that assumed an important geopolitical position between the east and the west. The new political circumstances favoured not only the development of abstract art – especially among Zagrebian artists, architects and designers and the founders of the group EXAT 51 – but also the development of a modern educational model that stimulated freedom of critical thought, creative expression and experimentation in the fields of architecture, art, and design.

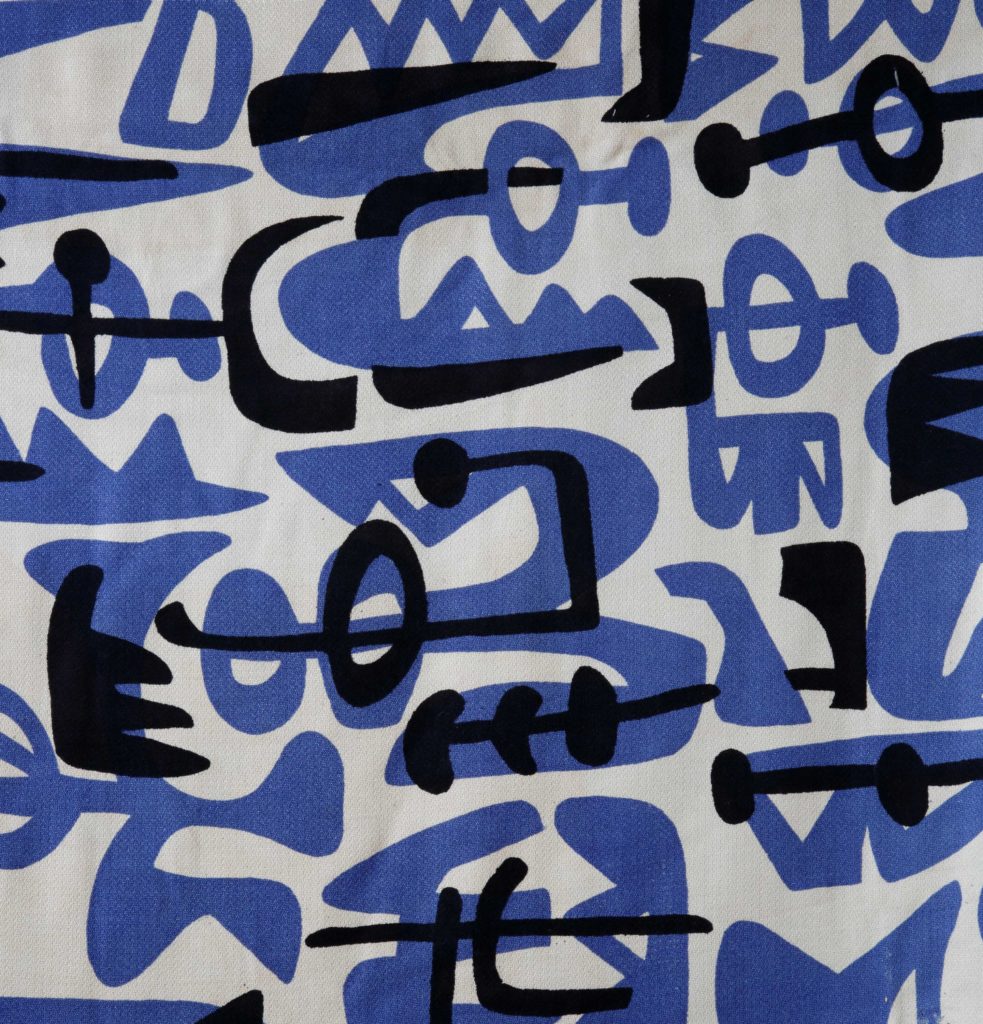

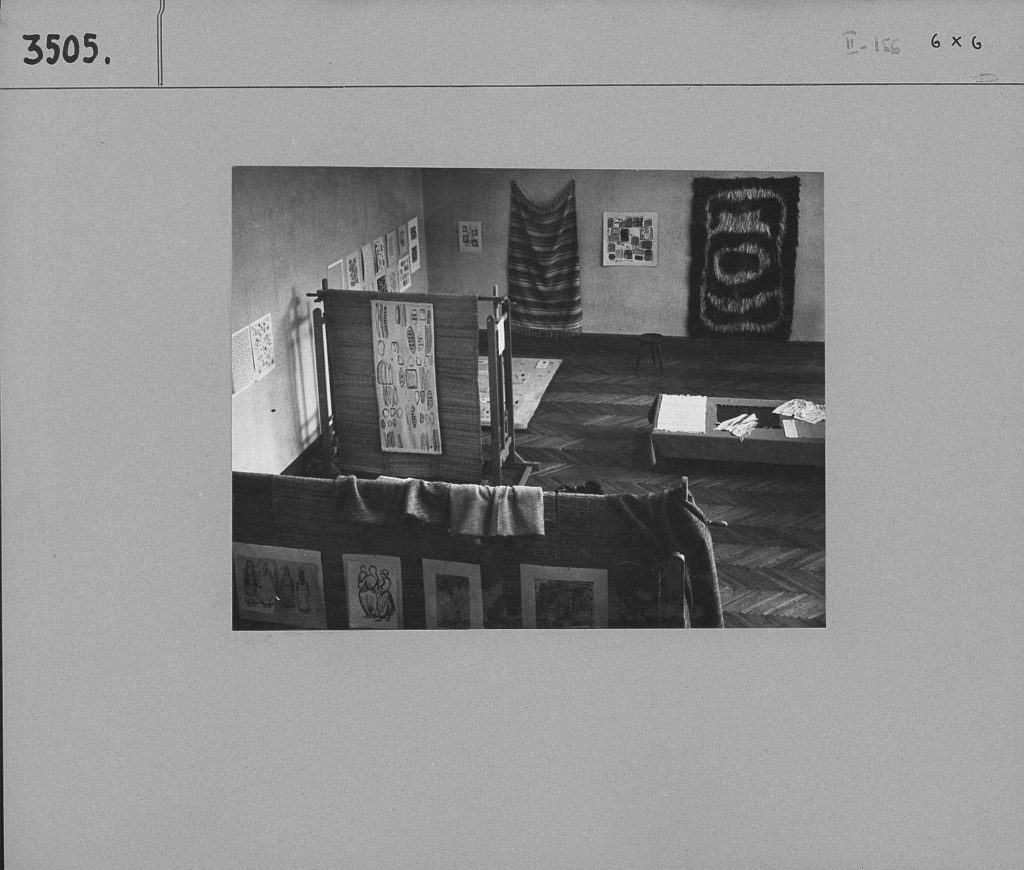

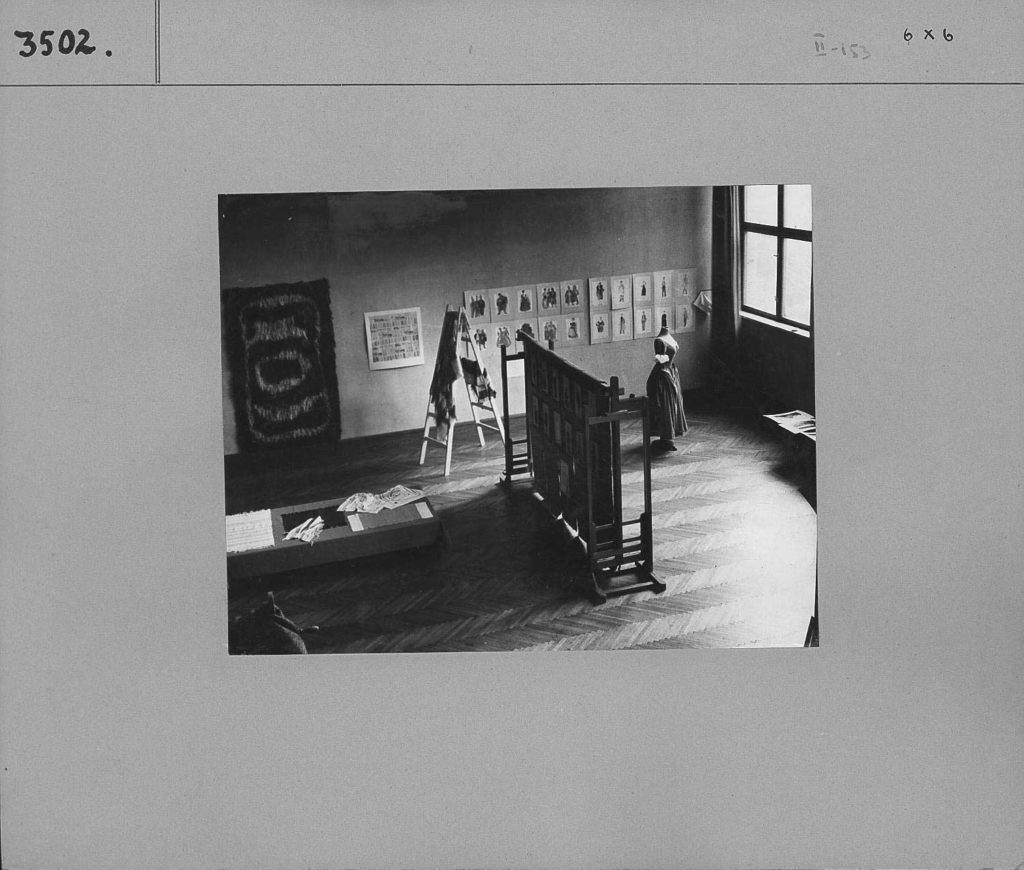

The Academy’s curriculum was based on the model of the Bauhaus, centred on the preliminary course followed by specialist studies in architecture, sculpture, printmaking, textiles, ceramics and painting. The aim of the study programme was to educate people who would apply aesthetic and fine art criteria to the design of industrially produced objects. Among the more distinguished professors at the Academy were also architects Vjenceslav Richter and Zvonimir Radić, members of the group EXAT 51, who conveyed their progressive attitudes to students within the framework of the architecture department. There, Richter taught construction and planning, while Radić held lectures on industrial product design and contemporary spatial concepts. Richter stated that the objective of the curriculum was ‘to bring up a cadre of people who would master the method of interior design planning while relying on contemporary scientific achievements’. In this, we recognise the presence of the influence of the Bauhaus principles.

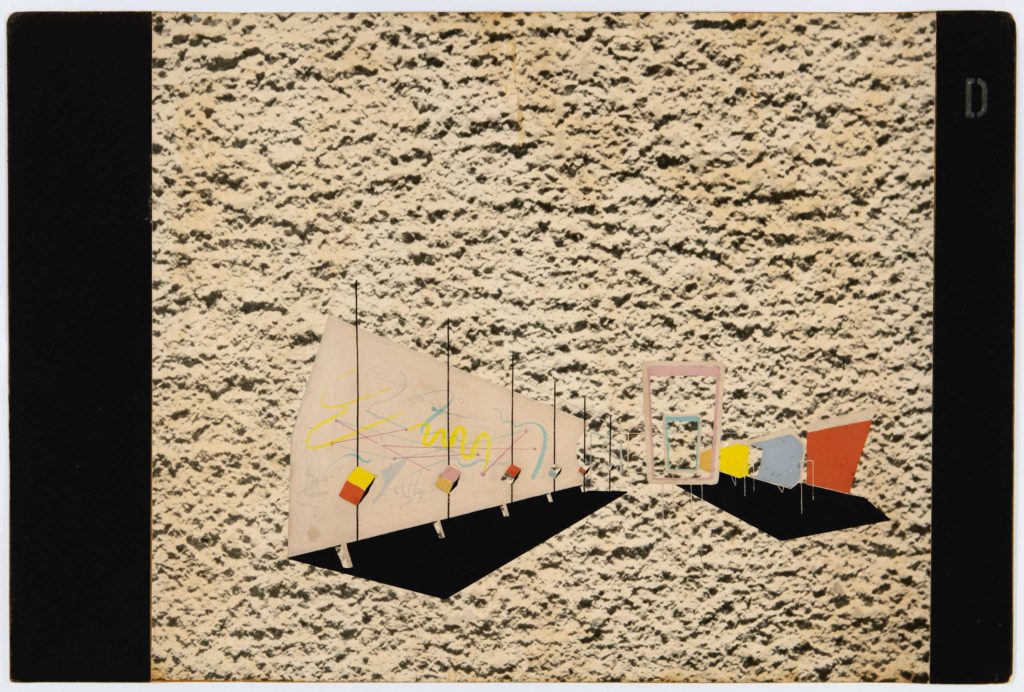

The fate of the Academy was similar to that of related institutions; it operated briefly, and the underlying reasons for its termination were quite possibly political. However, its far-reaching influences can be observed in the works of a generation of students and, in the wider sense, in the architectural and artistic creations of authors close to the Academy, albeit with different educational paths. It is in this light we must view the Yugoslav Pavilion at the 11th Milan Triennial in 1957, one of the most notable post-war projects designed by a group of architects, painters, sculptors and textile designers, who were former students and professors at the Academy, and other authors with similar creative principles. This creation was awarded the prestigious Silver Medal at the Triennial; unfortunately, such a successful form of collaboration, in which the idea of a synthetic approach was implemented, was never repeated. However, even though the goals of the Academy were never fully achieved, most of its students kept applying – in their independent activities and guided by the principle of ‘synthetic approach’ – the acquired pedagogical principles that had their origins in methods of the Bauhaus.