Black Mountain College (BMC) was an experimental, interdisciplinary school located near the Blue Ridge Mountains in North Carolina. The groundbreaking place of teaching and learning was founded in September 1933 with 12 tutors and 22 students. It was dissolved in 1957 due to ever-dwindling numbers of students and financial difficulties. Alongside Vkhutemas and the Bauhaus, the college is one of the most influential educational experiments of the 20th century. The contributors include a remarkable number of renowned cultural figures, ranging from Anni Albers to John Cage, from Richard Buckminster Fuller to Cy Twombly, from Beaumont Newhall to Ruth Asawa. Today, the ideals and methods of BMC continue be highly influential for a number of progressive educational models and in the arts.

The foundation of the college was incentivized by an internal dispute at Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida, in the early 1930s. This was triggered by the approval of a new curriculum based on the eight-hour day. Talks and lectures were abolished; time and space for autonomous research, studying or learning were no longer available. The classics scholar John Andrew Rice and other colleagues and students revolted against this model, which was regarded as a conveyor belt approach to education. Soon thereafter, the professor and all those who had sided with him were dismissed. With this, the frequently-discussed question of an ideal college became suddenly topical.

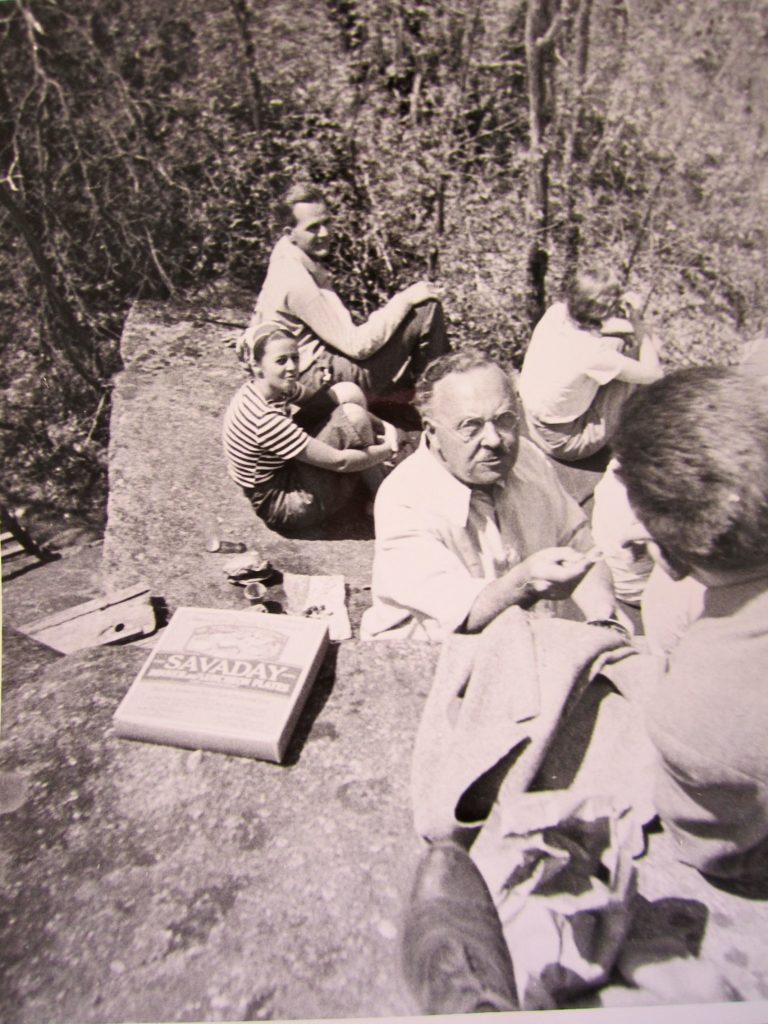

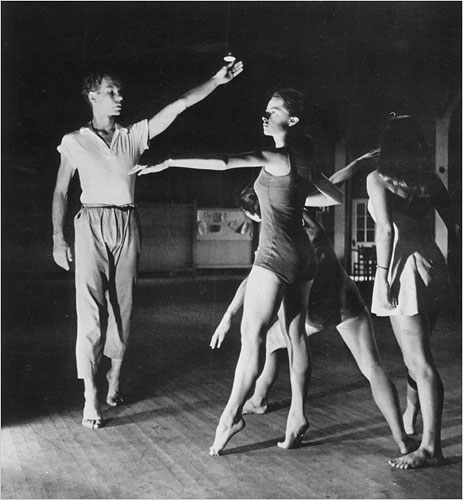

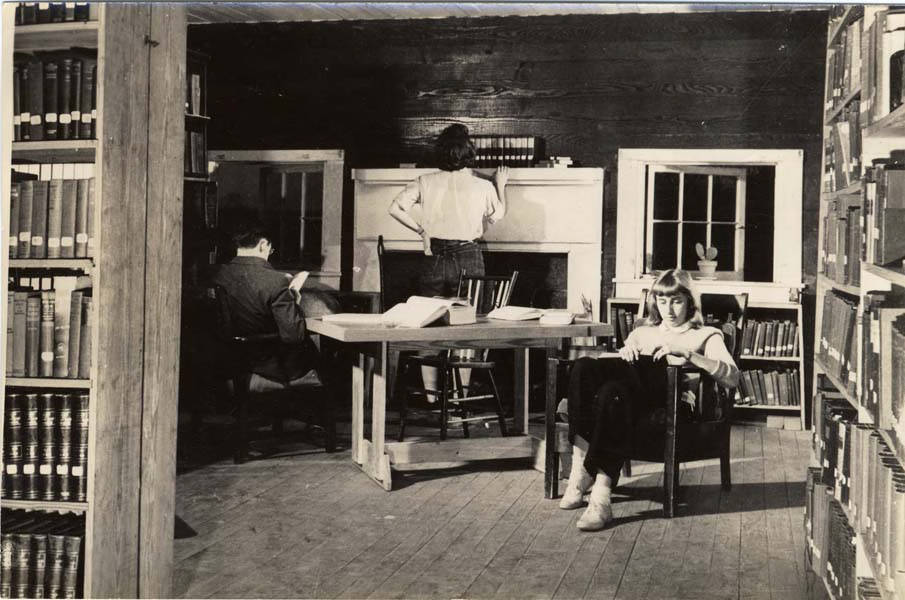

When founding BMC, Rice and his colleagues had a far better idea of what a college shouldn’t be than what it ought to be. Thus, the initial plan was to work in practice on a college based on the principle of absolute independence. They envisioned a “close, small world” with many visitors. The nascent college saw itself less as an institution than as the first step towards the realization of a form still to be found. Numerous academics, artists and students were involved in this form-finding process, among them many refugees from Germany and Central Europe. They included Josef and Anni Albers as well as Xanti Schawinsky, Walter Gropius and Lyonel Feininger, who had been active at the Bauhaus. The mathematician Max Dehn, psychiatrist and philosopher Erwin Straus, dancer Elsa Kahl, conductor Heinrich Jalowetz and music scholar Johanna Jalowetz were also among the emigrants who brought European modernism to Black Mountain.

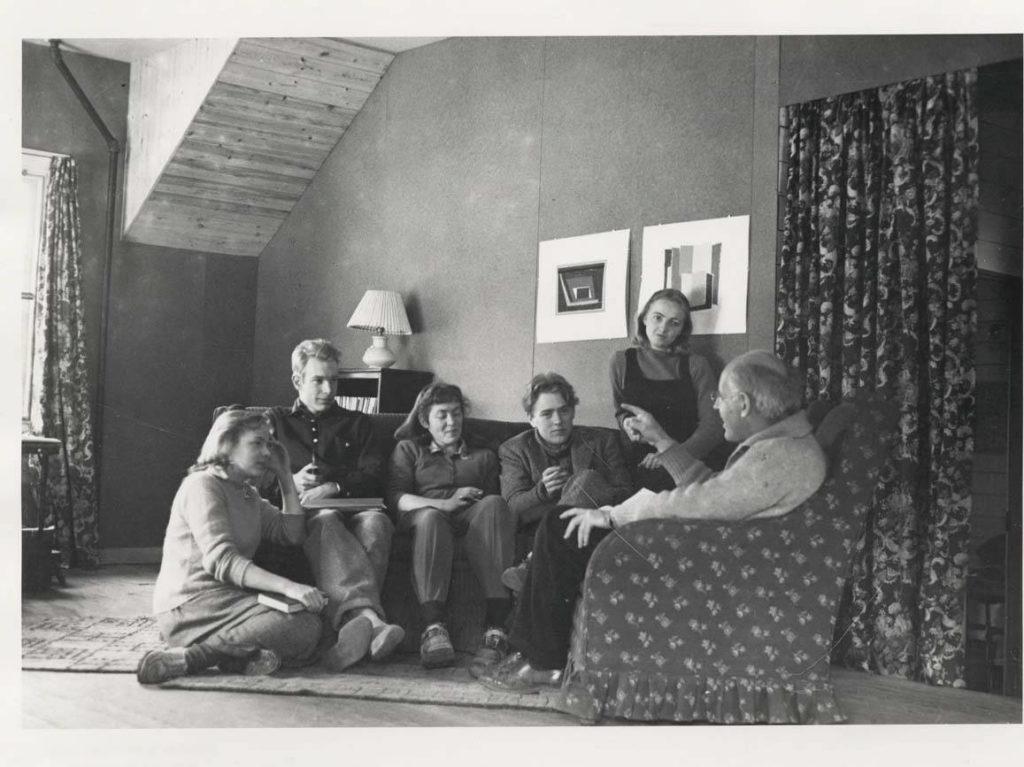

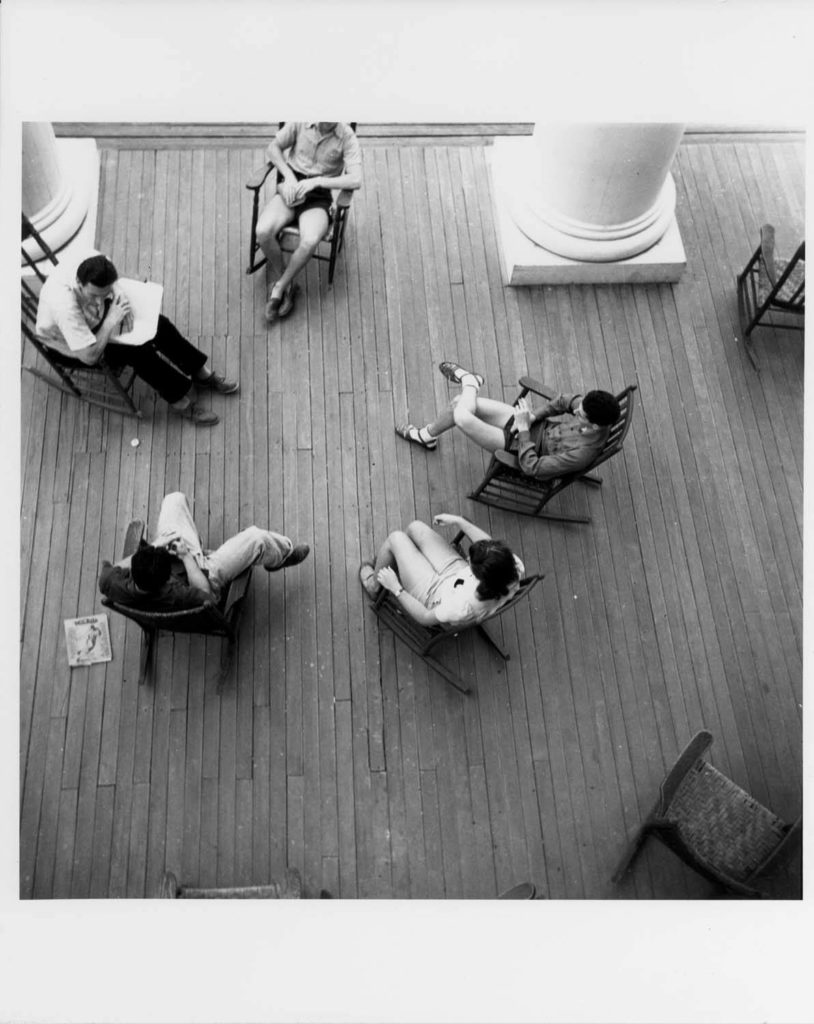

In the spirit of the American philosopher John Dewey, for whom for the acquisition of democratic values was dependent on experience- and practice-based learning, the BMC model attached no importance to a well-rounded curriculum. From antiquity studies to quantum physics and everything in between, it was not the content of a subject that educated, but the experiences which dealing with that subject generated. The fact that the first professoriate at BMC was put together arbitrarily was thus unimportant to Rice, as was the circumstance that the curriculum relied on the constantly fluctuating makeup and mood of the group. What was important to him was to teach democratic behavior as both a means and an end. The only subject that he regarded as essential, at least in the early stages due to his process-orientated methodology, was fine art.

The students were advised to study as many scientific and arts subjects as possible and to further hone their technical skills. There was no fixed syllabus. Two later directors, Josef Albers (1941–1949) and Charles Olson (1951–1957), retained this interdisciplinary, autonomous approach. This experience-based and experimental methodology especially benefitted the summer academies that took place from 1944, which are invariably highlighted in the historical narrative. It was in this context in the summer of 1952 that an event organized by John Cage evolved into what was subsequently described as the first “happening.”

Black Mountain College was shaped equally by the financial challenges of establishing it and by the people who lived, taught and learned there. Following his experiences at Rollins College, Rice wanted at all costs to avoid having a governing body and, especially, the associated board of trustees. He was well aware of the threats to academic freedom which the many “businessmen” officiating on boards of trustees and in administrative positions in the USA presented. But because he rejected the USA’s career and result-orientated performance structures, government subsidies were also unavailable. The college was thus dependent on gifts, donations and study fees. Due to the lack of a governing body, the funds were rather modest and usually earmarked for a specific purpose. This resulted in a professoriate which earned very little and students who paid a lot. From the outset, the college struggled with financial difficulties. Ultimately, these led to its closure.

The degree to which BMC achieved its aims and was able to realize its vision remains controversial. According to the co-founder and guiding spirit Rice, the project failed due to its absolute reliance on an as yet non-existent artistic subject. By contrast, the last director Charles Olson was firmly convinced that the process set in motion in 1933 would be ongoing. Even after the physical dissolution of BMC, the pioneering experiment lived on in the more than 1000 people who played a part in it. The lasting relevance of the experiment is less in question, as the number of artists and free educational initiatives that cite the college and its contributors prove.