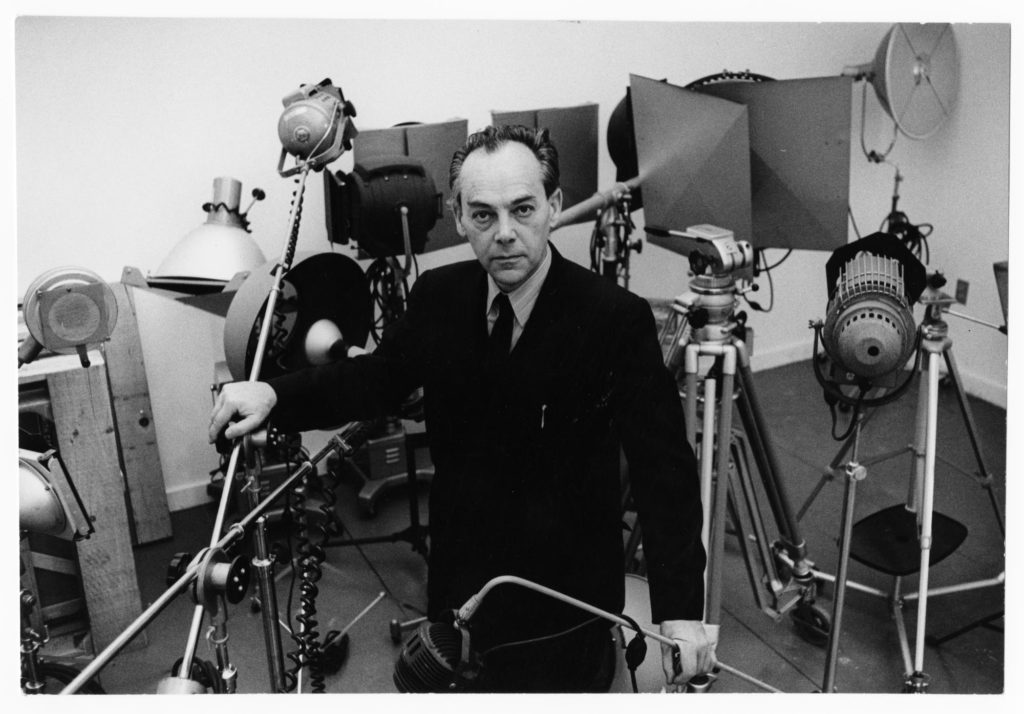

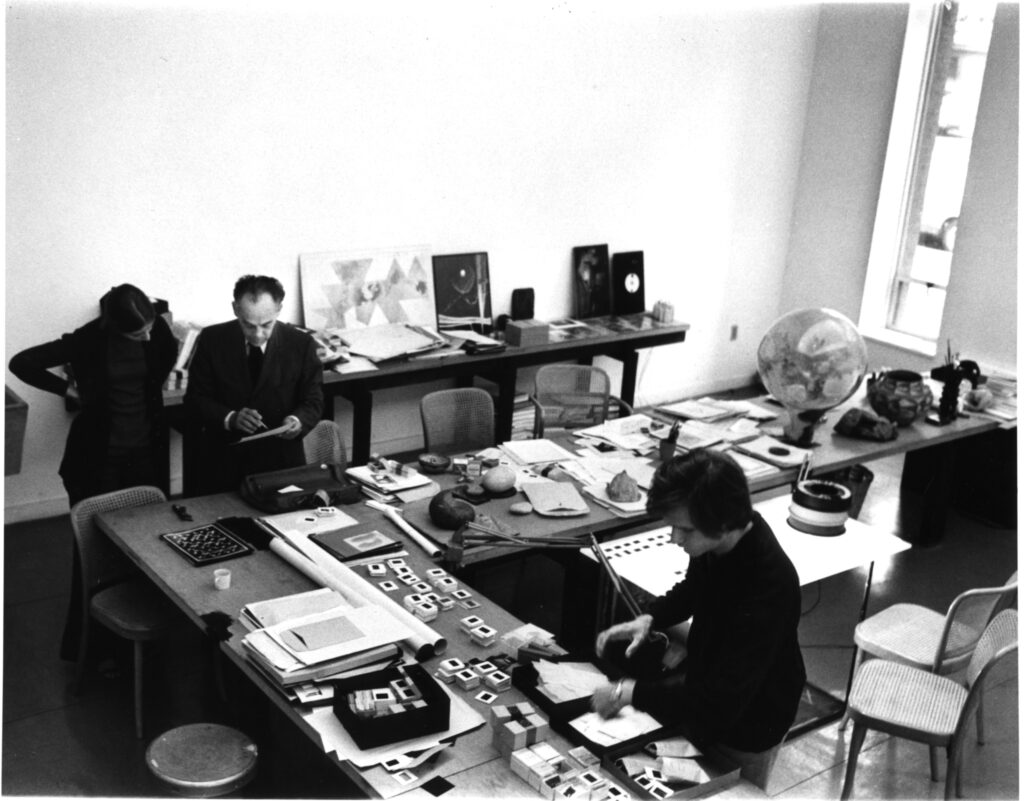

Founded in 1967 by artist, designer and visual theorist Gyorgy Kepes, the Center for Advanced Visual Studies (CAVS) at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) facilitated interdisciplinary projects uniting the visual arts with science and technology. Kepes described the Center’s mission as cultivating ‘idioms of collaboration’; by bringing artists to MIT, he hoped to encourage new forms of experimental creativity. The concept was modelled on the mid-century think tank and explicitly recalled Princeton University’s Center for Advanced Study.

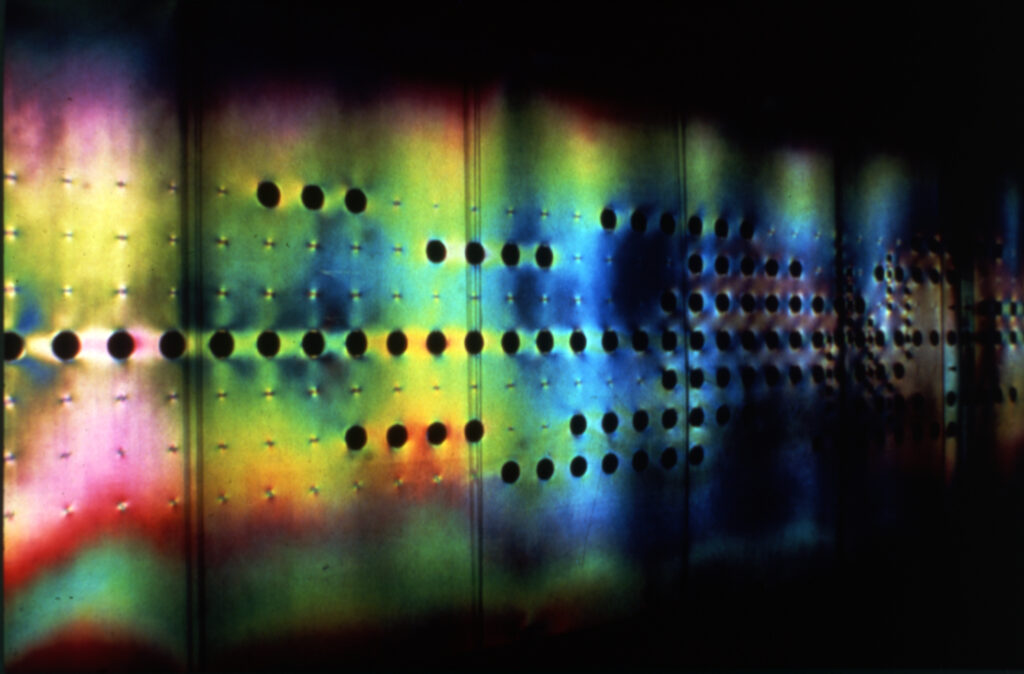

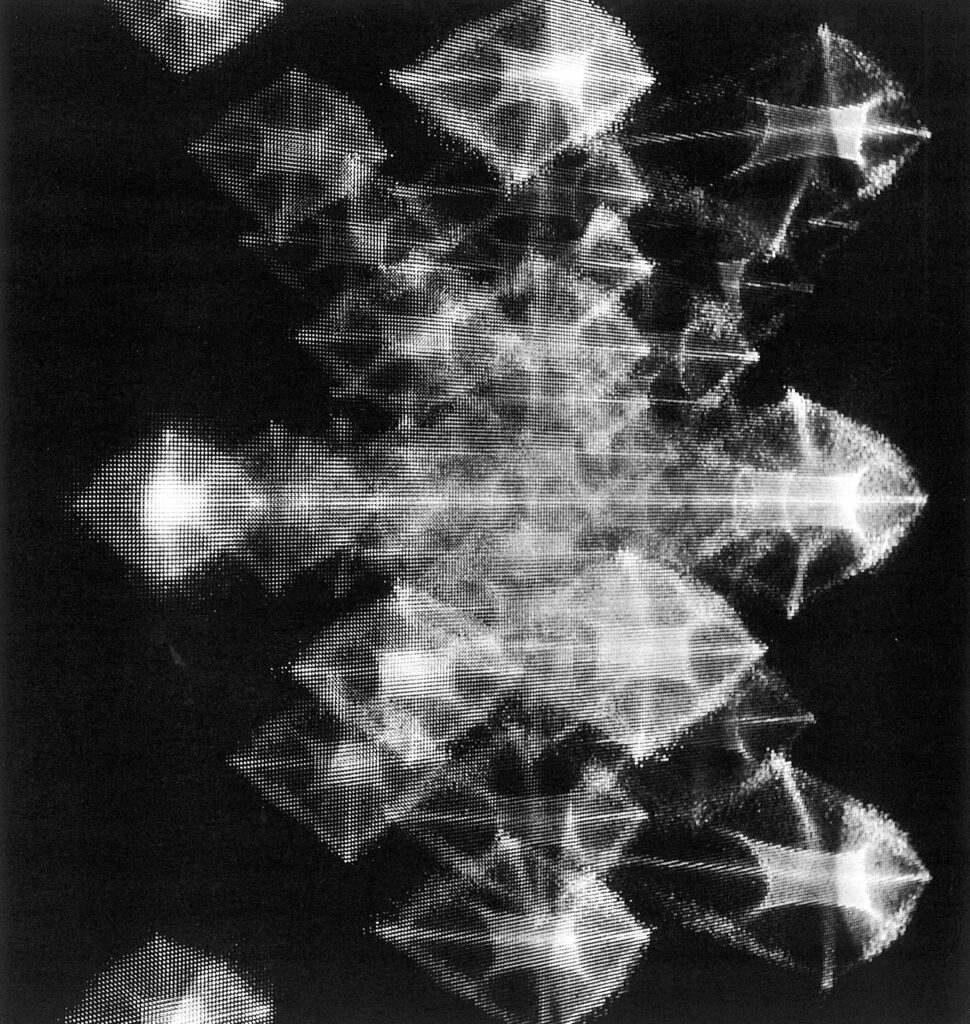

In contrast to the Center’s ambitions, its realised projects were immediately entangled in controversy. The Center organised its first collaborative exhibition at MIT’s Hayden Gallery in 1970. An elaborate new media spectacle titled Exploration (figure 4), the exhibition showcased the work of the Center’s inaugural fellows: artists Jack Burnham, Ted Kraynik, Otto Piene, Harold Tovish, Wen-Ying Tsai, Stan Vanderbeek and Takis Vassilakis. It created a technological simulacrum of the natural world through motorised sculptures, electric lights and synthetic materials like polarised plastic.

The response was brutal. The art critic Lawrence Alloway denounced the show as a ‘frivolous and gross fantasy of technology’. His reaction mirrored the reception of similar art world projects. Both the Art and Technology (A+T) Programme at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and the performances enabled by the organisation Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) were largely described as failures. The reaction reflected an anti-technological sentiment that intensified as US involvement in Vietnam continued; to many, science and technology were inherently tied to weapons and warfare.

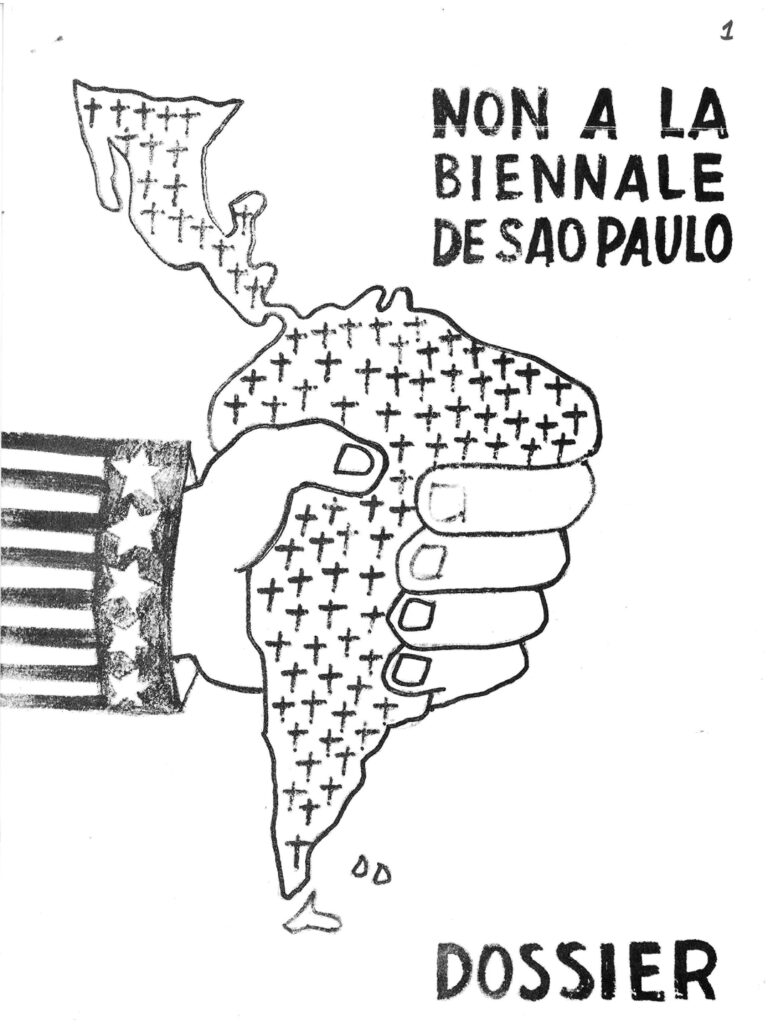

This critique became commonplace at Kepes’s CAVS. In fact, Exploration was first organised by Kepes as the US contribution to the tenth São Paulo Biennial, but Kepes was forced to cancel the original show after nine of its 23 artists boycotted it. Their target was Brazil’s military regime, which came to power in a 1964 coup d’état—one supported by the US government. The artists’ protest statements circulated in an infamous dossier titled ‘Non a la Biennale de São Paulo’. Its cover image elegantly represented the imperialism of US foreign policy.

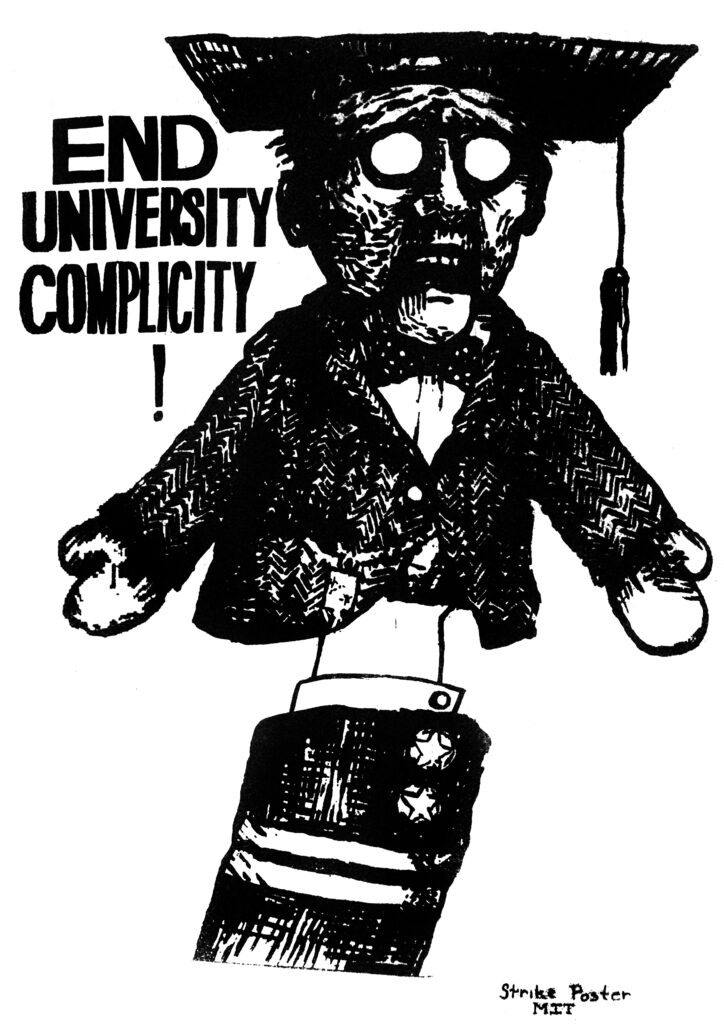

The most charged statement in the protest dossier was a letter by artist Robert Smithson to Kepes that implied that Kepes was complicit with war—even though he was a committed pacifist who opposed the war in Vietnam. ‘To celebrate the power of technology through art strikes me as a sad parody of NASA’, Smithson wrote sarcastically. ‘If technology is to have any chance at all, it must become more self-critical. If one wants teamwork he should join the army. A panel called “What’s wrong with technological art” might help.’ The letter echoed the anti-war protest then erupting at MIT, which was directed the institute’s burgeoning defense research. Some of these protest interventions specifically fixated on Kepes and his Center.

This defining episode reflects the core contradiction at Kepes’s CAVS: the Center introduced a remarkably innovative way to create art across conventional disciplines and boundaries, but in doing so, it also became entangled in the military-industrial complex that defined the era of the Vietnam War.