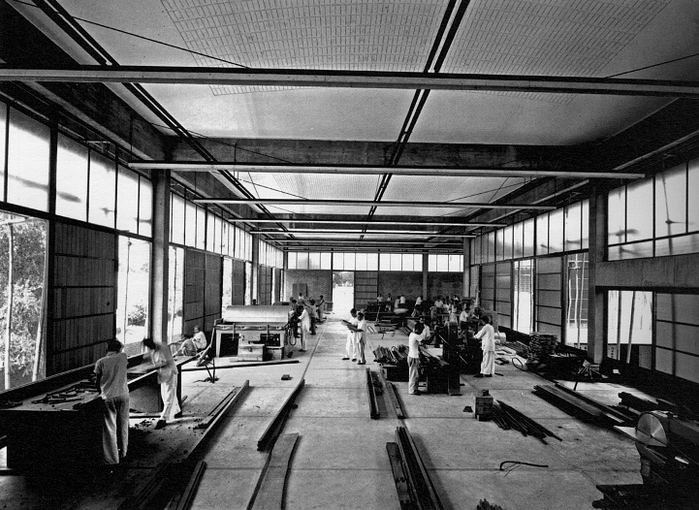

Established in 1961 to set a foundation of design as a tool for nation-building after decolonisation, the National Institute of Design (NID) in Ahmedabad became the first institution for formal design education in India. At its inception, the strategic collaboration with HfG Ulm placed the NID within a strong international network of design cooperation that emerged from the Bauhaus. At the same time, in a country with a rich cultural legacy of art and craft – an undertaking to shape the modern design future, language, and attitude on a postcolonial ground itself presented an immense challenge and responsibility on the trailblazing institution.

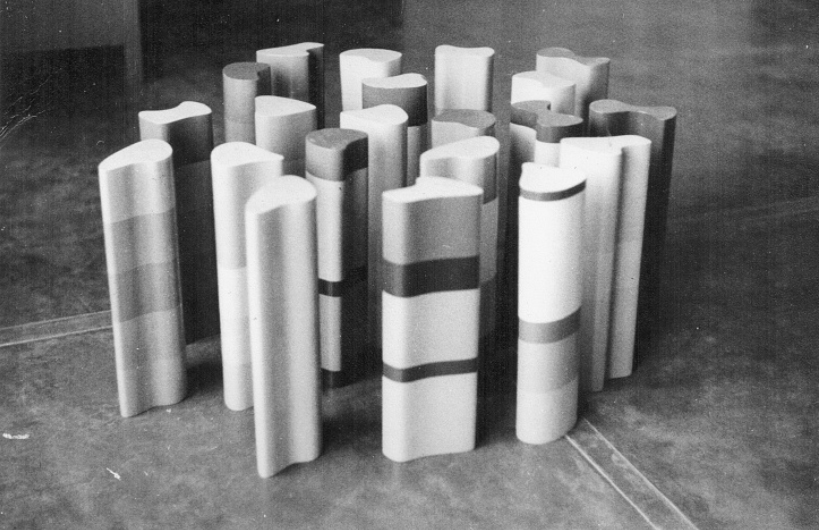

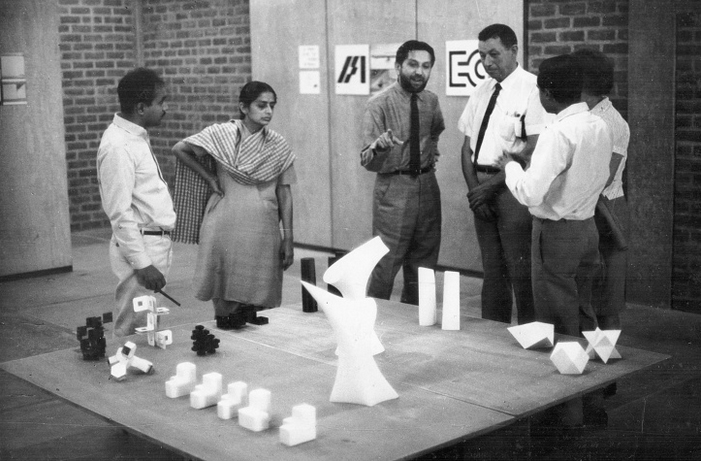

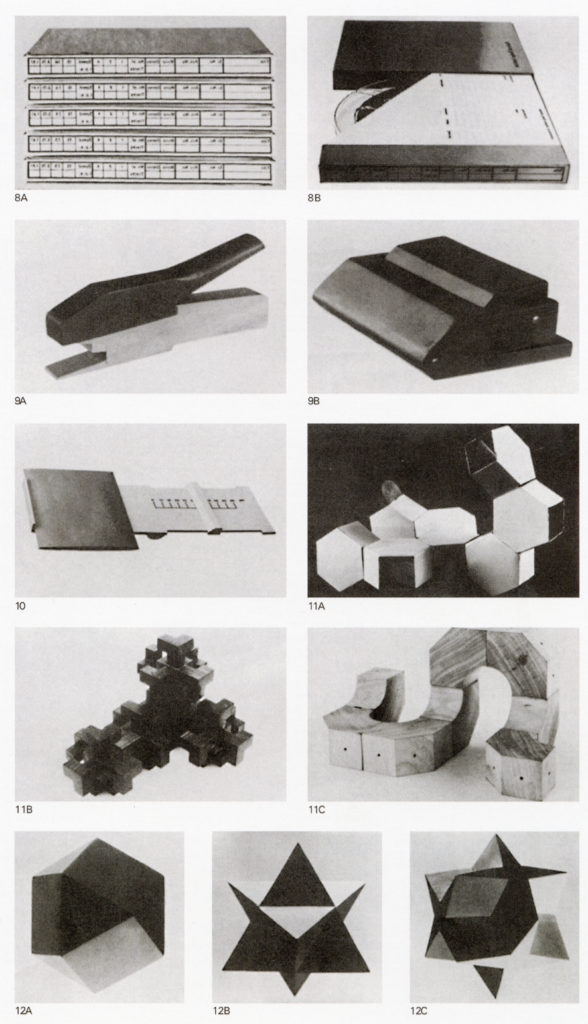

The India Report by the American designer duo Charles and Ray Eames outlined a compelling case for the need for an institution that draws from the nation’s heritage of culturally evolved design practices to define modern industrial design. Thus, the thoughtfully structured Foundation Programme at the NID intended to amalgamate design pedagogies of the Bauhaus and Ulm while developing unique features to respond to the Indian reality. In the process, the campus, the city, and the country became sites and subjects for progressive and independent design education which aimed to provide a better standard of living for Indians.

Against the backdrop of Western notions of modernisation which were exported to developing countries, the NID sought alternative, postcolonial practices for economic and social change. They aspired to disassociate themselves from the Western hegemony which linked design with formal aesthetic values and to align themselves instead with vernacular and ‘appropriate’ technologies in the design of objects of everyday use. Later, the NID became an important transnational hub for this new definition of design that leaned away from the Western understanding. Consciously steering ahead from placing industrial design at a hierarchically superior position that defined modernity, the goals that the NID laid out for itself were to first critically discuss the equivalence of design from a conceptual standpoint, as it had existed throughout the nation’s history – to acknowledge an organically and culturally evolved design process before setting the stage for a learned design process.

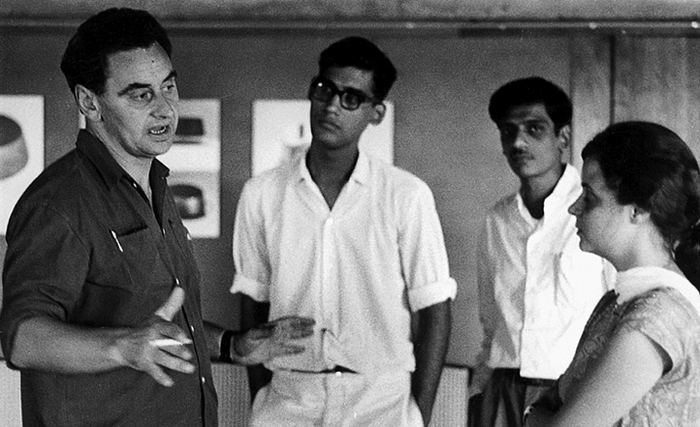

As a flagship for a new India, the NID was confronted with the task of integrating low-income consumers and producers from a mostly rural population into design thinking while simultaneously responding to the dynamics of a modernisation process orientated towards industrialisation. Notable educators H. Kumar Vyas and Singanapalli Balaram in their writings and lectures continually emphasised the search of a context for the Indian designer – one that holds a unique relevance for the immediate lifestyle needs observed within the Indian environment, accounting for its social, political, economic, and cultural frameworks, of past and present.

This approach has been significantly apparent in the NID curriculum: for example, first-year students were required to study local handicraft cultures in so-called craft documentation. Especially in a culture where the transfer of artistic knowledge has primarily remained oral, where written records mention the prevalence of art but have seldom documented such ubiquitous wealth and heritage of kala, where even the rigorous Guru-disciple training involved a high amount of tacit understanding developed over time – designing design education as a time-bound curriculum itself posed an unprecedented complexity and challenge.

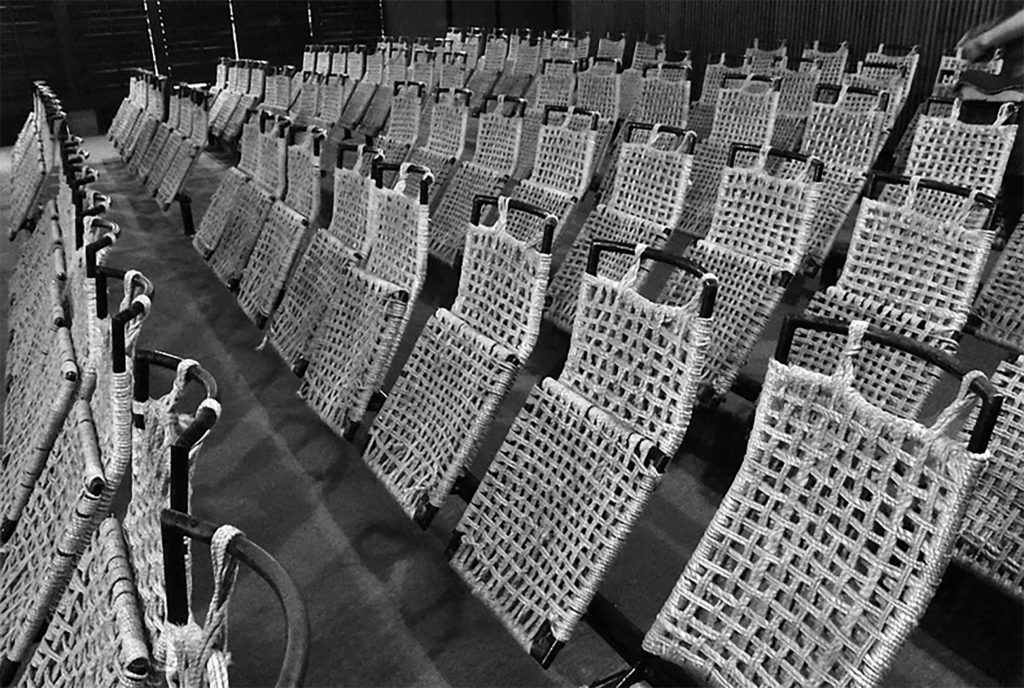

Ashoke Chatterjee, another prominent educator at NID points out that the marketplace is the ultimate testing ground for design. One remarkable project worth highlighting, where the design training imparted at NID was tested for its relevance, was in the economic development of the Jawaja block – one of the most geographically challenging and socially marginalized regions of the state of Rajasthan. Although not primarily a craft project, it evolved as a collaborative experiment between NID and the Indian Institute of Management (IIM), Ahmedabad, with the mission to build self-reliance in the rural ecosystem. Craft became central to this project in leveraging international market access for the cottage industry, thereby integrating modern design language with existing resources of people, traditional knowledge, and skills.

NIDs are still active as state-run education and research institutions for industrial, communications, textile, and IT-integrated (experimental) design in Ahmedabad, Bangalore, Kurukshetra, Vijayawada, Jorhat and Bhopal. They are under the authority of the Indian government’s Ministry of Commerce and Industry and have been recognised as Institutions of National Importance according to the National Institutes of Design Act 2014.

Further reading:

- Singanapalli Balaram. Thinking Design. Ahmedabad: National Institute of Design, 1998.

- Suchitra Balasubrahmanyan. ‘Designing Life in India’, in: Bauhaus Imaginista, ed. Marion von Osten and Grant Watson. London/New York: Thames & Hudson, 2019.

- Regina Bittner, ‘On Behalf of Progressive Design: Two Modern Campuses in Transcultural Dialogue’, in: Moving Away (Bauhaus Imaginista, 2018-2019).

- Ashoke Chatterjee. ‘A Route to Self-reliance’, interview by Carolyn Jongeward, October 20, 1997. Online, accessed 6 September 2023.

- Charles and Ray Eames. The India Report. Ahmedabad: National Institute of Design, 1997.

- H. Kumar Vyas. ‘Design History: An Alternative Approach’, in: Design Issues 22/4 (October 2006), pp. 27-34.